Texas Treasures

Moody Anderson and His Western Warehouse

By Marc Savlov, Fri., Nov. 3, 2000

It's high noon, midweek, not long ago. I'm tooling westbound on Highway 2244, 20 or so miles out of town -- I've been sworn not to give a clue to the exact location of my destination. Too fast, I spot the downward slope off to the side of the road that marks the entrance to my destination, downshift roughly, tee-off the soccer mom in the SUV that's been tailgating me for the past quarter mile, and cut the sharp left that takes me through a battered cow-gate. Not far now.

Despite the recent rains, the dirt track that cuts through the scrubby lot is still hard-packed, and I jounce another eighth of a mile or so back through the wilting greenery and through yet another gate until I finally catch sight of the thing I'm here to see. The outside of it, anyway.

It's big, too. Everyone told me it was big, but, you know, hey, I didn't think it was this big. It's a warehouse, as plain and ordinary as they come, sitting in the middle of what probably used to be, maybe still is, a pasture, out far west of Austin. There's an old-timey wagon off to the left, sitting in the field, looking lonesome and sorely in need of a new coat of paint and maybe a dray or two to hitch it up to.

I pull in, park beneath one of the cluster of trees that surround the structure, get out, and walk over to the entrance. There's a truck, like a mover's van, backed up to the opening, and I can see a couple of men in T-shirts and jeans standing there talking. They look like they just got done working.

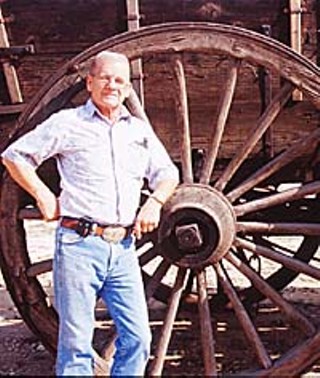

"I'm looking for Moody Anderson," I tell them, and one of them gestures to a fellow just inside the warehouse doors. He's not as tall as I'd pictured him, maybe 5-foot-7 or so, with the kind of silvery GI brush cut Audie Murphy probably favored, jeans, a workshirt, and an unlit stogie clamped between his teeth. His face is lined but clean-shaven, and he looks like his backstory, which is ex-U.S. Army, ex-Texas National Guard. He's 72 years old.

"That's me," he says with a quick grin, and right away I know -- don't ask me how, it's just a feeling I get, like I later imagine everybody gets, when they first meet the legendary Mr. Moody Anderson -- that this guy is all right.

"I've known Moody since Lonesome Dove, and then I've worked on lots of Westerns through the years and every time, we rent from him. I just want you to know this: We couldn't have made this movie in Austin if it weren't for him, because he has things that are different, that you could never find in Los Angeles. It's been really wonderful for him, too, because he hasn't done a lot of business in the last couple of years because so many films have gone to Canada to shoot, especially among the Western genre. We're very glad to have him here. He really made the show."

-- Barbara Haberecht, set decorator, American Outlaws

We shake hands and exchange pleasantries, and I step inside, out of the now and into the amazing past of Moody Anderson, a man who for the past 20 years or so has served as the Texas filmmaking community's one-stop center for old Western movie props. He leases out artifacts of the past to the six-gun cowpoke scenarists of the present, everyone from Clint Eastwood to Sammo Hung to Les Mayfield, whose film, American Outlaws (known during its shoot as Jesse James), wrapped in Austin last month.

This warehouse is where Anderson stores the mountains of relics he's collected in the 40-odd years he's been at it. I said it was huge, and when I ask Anderson exactly how many square feet we're dealing with here, he offers up a predictably gargantuan number and then adds, "but I'd rather you didn't put that in the article." Fair enough. Let's just go with "really big." You could dock a dirigible in here and still have room for, well, another dirigible, probably.

Taking the lead, Anderson, a guy who really does define the word spry, guides me into the labryinthine corridors. The air in here is redolent of the musty tang of time gone by, and my allergies will kick up something fierce later, but right now I'm trying to get my jaw up off the dusty floorboards and back in place where it belongs. Row upon row upon row upon row of shelving -- some of it looking none too steady -- lie ahead, around, above, each one covered with ... everything. I mean it: old tin cans, their labels still attached but peeling, rocking chairs, school desks, chairs, couches, bars -- whole bars! -- good paintings and bad, flags, saddles, gadgets, things I have no idea of what they might be. A riot of beige, brown, dusky old things from who knows where? I'm flummoxed. A stuffed mountain lion glowers down from its rusty perch, looking like it won the battle but lost the war. Coffins, stacked three high, some little more than pine boxes, the knotting plainly evident, tower overhead. Magazines, ledgers, books, advertisements for products and schemes that went belly-up decades before I was born line the walls. It's a cool, retro sensory overload like nothing I've ever experienced, and all the while Anderson is offering anecdotes and dropping history like other people drop cigarette butts. I stoop to pick up some knowledge.

"Back in 1988 we were doing Lonesome Dove. Moody at that time had a little place on South Congress called The Texas Trader, and that was, for me, a gold mine of stuff, you know? Set dressing. So we talked him into working with us, leasing us stuff, and actually ended up buying a lot of stuff, too. And he and his partner Terry Booth have been leasing props to me ever since. Moody's a wonderful guy, and because of him it's been possible to make period movies in this town. A lot of people have benefited from his willingness to kind of get into this business. I credit Moody with a lot of the success the film business has had in this town. To have some resource here that you can go to, with someone that's been collecting and housing stuff as long as he has, that's a rare thing"

-- Cary White, production designer, American Outlaws

"The first thing that I ever collected in life was blacksmith tools," says Anderson as he shows me -- surprise! -- enough rusting and gritty blacksmith tools to outfit an army of ironworkers. Anvils, prongs, little pointy things that do god knows what, stacked neatly beside each other, shelf after shelf. "I used to work in the Texas National Guard for about 32 years," he continues as we walk through the makeshift aisles. "And one day I was on my way home from work when I saw this sign that said, 'Farm auction, 1pm, Saturday.' I hadn't been to a farm auction in probably 10 or 12 years. So I went out there and they were trying to auction off these blacksmith tools but they couldn't get anyone to even bid on 'em. So I thought to myself, 'I think I'll buy some of this stuff,' and that's the first thing I began collecting. I had a chicken house full of blacksmith equipment, all of it iron and rusty-looking. Then I got started looking at signs, old tin cans, and from there on out I just went crazy, collecting everything I could get my hands on, really. Anything that was cheap and I could afford it, I'd buy it."

No foolin'.

By his recollection, that was back in 1961 or thereabouts, and Anderson, with one wife and three kids probably wondering just what the heck he was up to, hasn't looked back.

Now, I know a little about collecting and collectors myself, having gone through various stages of it in my own lifetime, from comic books to monster model kits and other youthful persuasions, but Anderson's warehouse is like nothing I've ever seen. It boggles the mind. Where else do you go if you need a turn-of-the-century cash register or receipt ledger? Where else could you go? Granted, there's not all that much call for many of the things I'm looking at -- say, for example, the nearly new-looking can of Southern Select beer (or the J.R., or the Monterey), but if you're dressing a film set in the hazy Texas past and you need these period details, the little touches that mark the difference between bringing the illusion of the past to life or simply faking it, badly, then Anderson is your best friend. Hell, he's probably your best friend, anyway.

"We pretty much use some of Moody's stuff for everything. You can always find something that you need out there. We used a lot of it on Spy Kids and The Faculty. Just about every movie I've ever worked on in Austin, we always go out there first and see if there's anything that we can use, and there always is. And that's partly because we want to give him the business because we like him so much. He still goes to his warehouse every day. Usually when you go there, there's a bunch of his friends hanging around. It's kind of like the old country store in a way. That's the feeling I get when I go out there. There's people always just dropping by and sitting around, and there's Moody chewing on his cigar and climbing around the warehouse. Particularly for Moody, it's a social environment out there and not just a business. He really enjoys his life there."

-- Jeannette Scott, set decorator, The Newton Boys

"After I retired in '79," continues Anderson, "I decided to open up an antique shop because up to then I had everything stored in a chicken house over on Manchaca Road. So I opened up a shop over on South Congress -- probably the first antique shop over there.

"So I ran the shop for about two, three years, realized I wasn't making any money, and was wondering what to do. When Lonesome Dove came to town, Cary White, who was the production designer on the film, came into my shop and saw all the junk laying around and asked me if I'd be interested in leasing it out to the film company. He's the one that got me into the leasing business and since then it's been kind of a one-man operation. If I had a bunch of movies like [American Outlaws], two or three times a year, maybe I could hire a bunch of help to get all this stuff on the computer. The way it is now, if you want to know where my computer is, well, you're lookin' at it. Right here." Anderson taps his brow with his index finger. "That's all I need."

We continue walking through the maze of antiquariana, and I'm beginning to get a crick in my neck from all the gawking. We must look a sight, the two of us, me with a microcassette recorder in my hand, trying to catch the running commentary from Anderson, as he moves ahead and beyond me. I'm craning, looking this way and that, and thinking to myself: Even for 40 years worth of collecting, this is a lot of stuff. It seems there's no end to it. I could get absolutely, wonderfully lost in it all. Up ahead, on the far wall, there's mountains of textile goods, blankets, pillows, quilts, all of them old, old, old, and covered with stains so foul and grit so thick you could slice with a machete, heat it up, and sell it off to the highway department as blacktop. I can feel a sneeze or 30 dancing in the back of my throat.

"What's the strangest thing you ever came across?" I ask him.

"Well," he says, after a pause, "I had a picture that I picked up of John Wesley Hardin. A cabinet-card, which is a little piece of cardboard with a picture glued on it and the name of the photography shop down at the bottom. It was taken in El Paso, where John Wesley was killed in a saloon. The picture showed him laying there dead with all the bullet holes in him, and then it was sent to the San Antonio Express and on the backside it said 'This photograph was taken one day after John Wesley Hardin was killed. Note bullet holes, 1-2-3-4.' Well, it was pretty obvious where those bullet holes were, but they mailed that off to the paper and there it stayed."

Round about this point I'm thinking someone should call Bob Dylan and fill him in on this.

"I found it in a box of junk I bought for $35 and I eventually sold to an old boy for a couple of hundred dollars. But the last time it was sold, it sold for $45,000. People think I must not be able to sleep at night knowing that but it doesn't bother me. As long as you make a little bit of money, it's all right." He continues, "Now, if I had known that John Wesley Hardin and his brother were the only two in the first graduating class of Round Rock High School -- which they were -- I never would have sold that picture."

Anderson's a Round Rock native. He spent his infanthood in the same cradle his father did, the same one his grown children have used for their own kids. He is a collector in more ways than the obvious.

"I've worked on maybe a dozen films where we used Moody's stuff, most recently on American Outlaws. I was pretty much in charge of coordinating the construction of the town that we built out there on the Double C Ranch in Driftwood. We built a whole town of over 40 buildings, a courthouse square, and a street as long as a football field with buildings on both sides over this past, hot summer. It's probably the largest Western town in the United States right now. Once it was done, Barbara Haberecht, the decorator, got two or three truckloads from Moody, and once she started putting the barrels, the wagons, and all the rest of the stuff in the street it really started to come to life. We couldn't have done it as well as we did without Moody. He's also really good at finding stuff for us. If he doesn't have it, he'll snoop around and find it. He knows other dealers, other people in the industry, and he'll go to auction if he needs to find us something that he doesn't have."

-- John Frick, art director, American Outlaws

There's a cow skull grinning at me. A whole bunch of 'em, actually. Rugs and throw carpets line the walls over in this far end, lorded over by a mammoth saloon bar bedecked with intricate scrollwork that belongs to Anderson's partner Terry Booth.

Lately, there's been talk -- mostly from Anderson himself -- about how he's getting up in years and may be looking to pass his collection on to a younger hand. There have been offers made in the past, sure, but none that Anderson took to heart. When I ask various members of the local film community about this, to a person they feel that although that day may come, no one's in any hurry for it to get here. Anderson is like some fine, natural resource found only in Central Texas. There are big Hollywood prop houses out West, of course, but none remotely like Anderson's. And the people here, the people who have worked with Anderson and dealt with him on a yearly or monthly basis over the course of such locally shot films as Michener's Texas, Honeysuckle Rose, Red-Headed Stranger, Where the Heart Is, Varsity Blues, Office Space, Home Fries, Selena, Streets of Laredo, Bad Girls, A Perfect World, and Once Upon a Time in China IV would hate to lose the man even more than the man's warehouse. Part father-figure, part grand old horse-trader, I was told again and again, in no uncertain terms, just how irreplaceable Anderson is.

And about that last film, the Sammo Hung-directed, Tsui Hark-penned Jet-Li actioner? Anderson says: "They were the only people I've ever had a problem with. They ended up writing me out a hot check. All the other movies have been great."

When I ask Anderson if maybe the Texas Film Commission of the State of Texas Historical Agency might not be interested in caretaking his collection in his stead, he appears to brighten for a moment.

"I hadn't thought of that," he says.

Anybody listening out there?

"I'm 72 years old, and I'm going to have to part with it some time," he adds, unfired stogie still clenched in his right hand. "There's an old saying: We don't ever own all the old stuff, we just kind of acquire it. I'm just caretaking it for the next guy." ![]()