Study on Austin Murders Finds Random Shootings Rare. City Says Police Alternatives Can Help.

City collaborates with nonprofits to stop violence

By Austin Sanders, Fri., July 19, 2024

A recently published report analyzing gun violence in Austin confirmed two facts that Michelle Myles already suspected were true.

One, the overwhelming majority of people who killed someone with a gun, or who were killed by someone using a gun, during the year in which researchers studied were young Black men. And two, the vast majority of gun homicides occurred as the result of some kind of dispute – that is, not during the commission of some other crime like robbery or auto theft.

For Myles, whose job as program manager in the city’s Office of Violence Prevention entails identifying and supporting solutions to reduce gun violence, confirmation of those two facts has been illuminating. “Most disputes happen when no one is around except the people who are disputing,” Myles told the Chronicle. “And they’re getting resolved through taking violent actions which can often lead to homicide.”

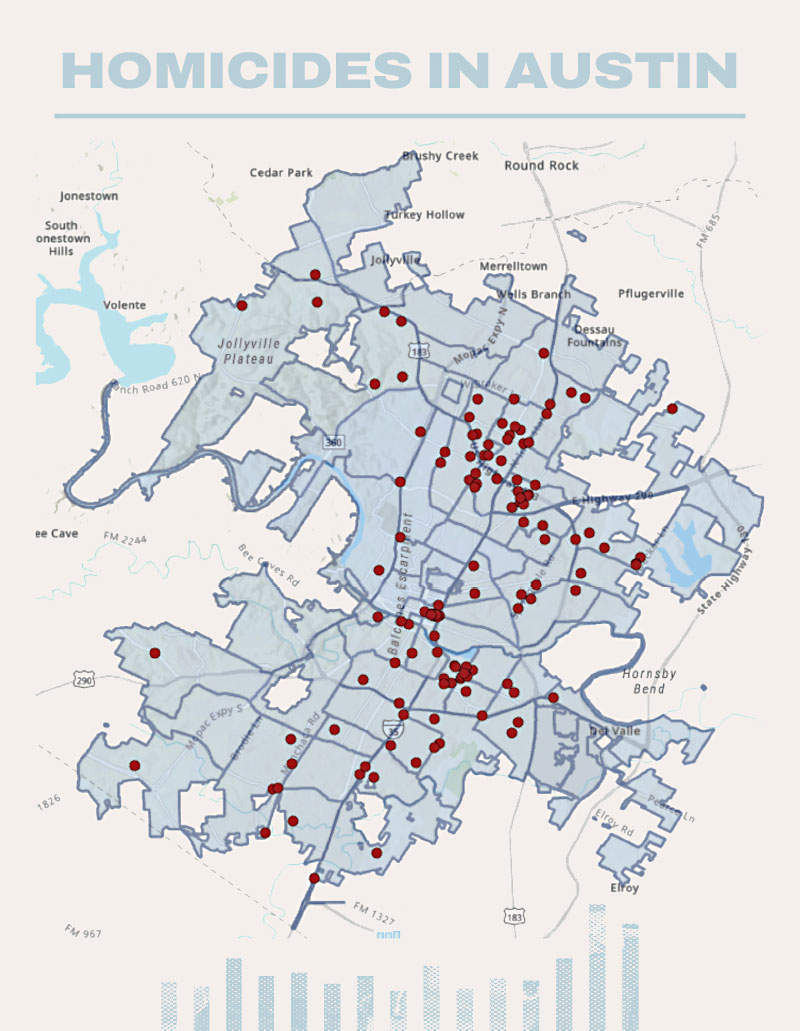

The information can be found in the report conducted by the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform in conjunction with OVP and the Austin Police Department, published July 2. NICJR researchers looked at a total of 142 homicides that occurred in Austin between 2021 and 2022 to gain a better understanding of where gun homicides are occurring, who is committing them, and why.

“For the work we do, it’s really important to know that information,” Myles said, “because then we can apply appropriate interventions. When a dispute is happening, how can we help those involved handle a conflict without violence?”

One intervention that is unlikely to be of much help: law enforcement. NICJR researchers found that the three most common circumstances leading to homicide were “instant disputes” (those that “occur suddenly between individuals” who have no prior relationship), personal disputes, and domestic disputes.

Myles said law enforcement does play a role in reducing gun violence – helping to keep guns out of the hands of people most at risk for gun violence and responding to shootings after they happen – but their ability to intervene in the disputes that researchers found most often lead to gun homicide is limited. Personal and domestic disputes are most likely to occur in private spaces less accessible to police patrol. Instant disputes may happen in public spaces, but in those situations, police are typically responding to violence that has already been committed – not preventing it in the first place.

There are other reasons law enforcement is ill-suited to addressing the gun violence problem. Gun violence is predominantly a problem in communities lacking in material conditions, Myles said. Jobs are scarce, housing is unaffordable, access to food is insecure. “When those material conditions are met, communities are more safe,” Myles said. Law enforcement is not designed to address those needs.

Another reason police may not be of much help: lack of credibility in the communities where gun violence is most frequently occurring. The people involved in disputes escalating toward gun homicide may be reluctant to call the police for help for a variety of reasons, Myles said. That means police will have fewer chances to intervene in these situations and less opportunity to prevent violence.

But people with trust in affected communities might be able to intervene, Myles said. Enter the “credible messenger” – someone working for a grassroots organization that already has roots established, who shares the lived experience of the individuals most likely to be a victim or suspect in shootings.

Researchers found that 59% of victims and suspects of homicide were between the ages of 18 and 34, with half of the suspects being 24 years old or younger. Black Austinites were highly overrepresented as both victims and suspects – Black people accounted for just 7.9% of Austin’s population during the study period, but represented 42.5% of homicide victims and suspects. Most of the homicides occurred in East Austin, particularly in the Rundberg/Georgian Acres and Riverside/Oltorf areas.

Most victims and suspects had “prior involvement with the criminal justice system” and had been arrested a total of 11 times by the time of their involvement in a homicide. Though, crucially, only a small minority of those prior arrests were for violent offenses.

One of the interventions OVP has already deployed is a partnership with three organizations – Life Anew, Jail to Jobs, and Hungry Hill Foundation – which are collaborating on an effort known as ATX Peace. Each organization already had an established presence in the affected communities and each brings a set of skills designed to address varying factors that lead to gun violence.

Life Anew specializes in conflict mediation, particularly among young people, so they can help at-risk Austinites develop tools for handling disputes without violence. Jail to Jobs helps people exiting the justice system connect with employment so that they can meet the material conditions that produce safer communities. Hungry Hill does a little bit of everything – case management, conflict mediation, connections to jobs and resources.

Chase Wright, Hungry Hill’s executive director, said part of what makes the efforts of his 25-person team effective is that they know the communities they’re reaching out to (Wright himself grew up in the Springdale neighborhood where Hungry Hill’s resource center is located). Many of his ambassadors were incarcerated at one point, too. “That’s a real intentional method,” Wright told us. “It’s impossible to do this work otherwise. The stuff you gotta know, you can’t learn in school. It’s kind of a blessing that these individuals are open to changing their lives and giving back to their community.”

Researchers found that, from 2008 to 2021, Austin’s homicide rate hovered around 4.0 (that means in any given year there were around four homicides for every 100,000 people living in the city), which was well below the state and national averages for the same time period. That shifted in 2021 when Austin’s homicide rate was nearly double the state and national average – a trend that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic that researchers have observed in virtually every other major American city. Since then, Austin’s homicide rate has begun decreasing.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.