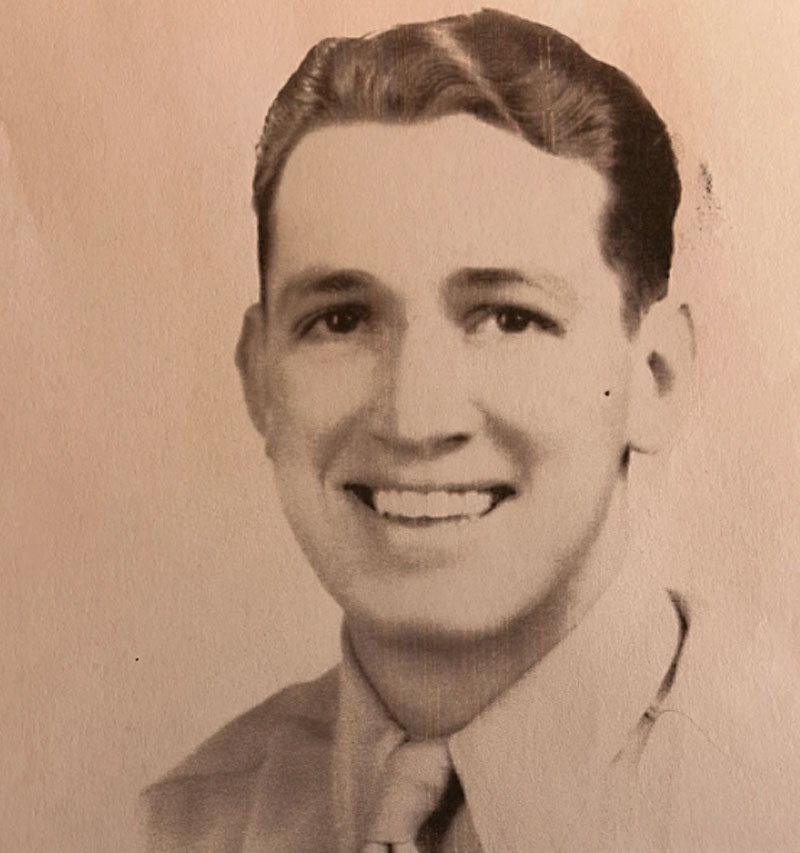

Austin Elders: Meet Stan Brooks, the 102-Year-Old World War II Vet Who’s Lived to Serve

He remembers Barton Springs before the cement

By Maggie Q. Thompson, Fri., June 28, 2024

Stan Brooks’ chances of surviving toddlerhood were slim. Now, at 102 years old, he may have the earliest memories in Austin of any resident alive today.

“I had double pneumonia when I was 2 years old. And I remember it,” Brooks said. “I remember the bedroom Mother put me in. It had a black potbellied stove with the outlet running through the ceiling. It was my mother and a lady she hired to help and they were with me 24/7. She put the rest of the family in other parts of the house and I never saw them. Even Dad was afraid he’d get pneumonia.”

In 1924, the advent of penicillin was still a few years away. So to treat Brooks’ infection, his mother heated yellow sulphur over the fire and put it on flannel material on his little chest. “It smelled like hell,” Brooks said.

Brooks was born in Elgin in 1922, the youngest child of parents born in the Victorian era. There, his family used a party phone (neighbors could listen in) and ate mostly chicken dinners, but sometimes also squirrel and rabbit.

In 1926, the family moved into a two-story house on 38th Street in Austin, near Burnet Road. Brooks said his parents wanted their children to get good educations, but they also opened a furniture store at 408 Congress Avenue.

“Congress Avenue at that time, I could walk anywhere,” Brooks said. “Of course, Austin has lost me. I mean the Austin I loved – there was a population of about 38,000. When we got to 75,000 I thought, 'This is perfect.’”

The Thirties were some of Brooks’ favorite years. He loved how people dressed – whether in dresses from Scarbrough’s or jeans (with no holes!). His family’s home was always a friendly space, too. The Brooks kids were used to having Black friends, as both his mother and father befriended Black neighbors in Elgin. In the Thirties, Brooks fondly remembers playing at a Black friend’s house and in Waller Creek together.

Brooks didn’t know if mixed-race friendships were unusual at that time because he said his parents didn’t mention it, but he knew Barton Springs was still segregated. It would be for another 30 years.

He thought back to the first time he saw Barton Springs Pool and said it must’ve been 1929 – which happens to be the year that the permanent lower concrete dam was constructed (prior to that it was dammed with big rocks that had to be replaced after every flood).

“I do remember Dad taking me and some friends there on a Saturday morning,” Brooks said.

“He happened to have a ’29 Dodge coupe.” That was soon replaced with a ’31 Chevrolet, then a ’32 flathead V8 Ford.

Brooks remembers the work trucks for the furniture store, because he’d help his older brothers deliver furniture in them. He also worked at Barton Springs one year. “I remember the ’36 flood flooded up to that second floor of the pavilion and mud that deep,” he said and motioned with his hand. “Me and some other kids got a job cleaning the mud off, and they gave us a season pass, which amounted to about $4 or $5.”

That was a great reward, because he spent much of his youth at Barton Springs, picnicking and swimming. He also danced at Gregory Gym, where big bands played, including Wayne King.

When Brooks graduated from Austin High in 1940, he moved to California where one of his brothers lived. There, he was working at a Lockheed airplane factory when Pearl Harbor was bombed. “What I thought about is, well, my brothers and I are probably going. We all did,” Brooks said.

Brooks wanted to be a pilot, but when a physical found he was red-green colorblind, the plan changed. After requesting to return to Austin, he volunteered to become a crewman on a B-17 Flying Fortress. Training as a gunner involved high-altitude flights in the open-air planes. His ears didn’t just pop during flights – they bled. As a result, he was grounded for medical treatment. Again, plans changed.

Ultimately, he was assigned to an air group of Douglas A-20 and A-26 medium bombers, which flew relatively low to the ground to attack. He spent most of the war in Italy. Getting there took nauseating trips on a converted banana boat, and being packed into a cattle car on a train, always under threat from German soldiers. Despite the stress, Brooks never took up smoking. (He noted: “I smoked a Swisher Sweet when the war ended, I guess.”)

“Generally speaking, you get friends and you share with each other and that gives you a great deal of comfort,” Brooks said. “And we were nervous at times, not relative to the infantry though. But we had, you know, bombing and that sort of thing, sabotage, and we got pretty well accustomed to it.”

During the war, he wrote his mother more than 385 letters. “Mine are not historically very interesting because I sanitized it. I did not ever talk about the tragedies, the deaths, that part,” he said. “My mother had the toughest time in the war, tougher than her kids. She lost her husband in ’44 and had three kids overseas. She had it tough. Dad said I wish I could live to see my kids come back. Pretty sad. But all of us came back.” He said that was incredible. He knew a family that lost five brothers. “I often think about their mother.”

After the war, Brooks graduated from UT-Austin with a B.S. in education. He spent decades in schools, working as a boxing coach, school counselor, and principal.

Having never married or had children of his own, certain students became like his own kids. Today, he has framed photos of these pupils in his house in North Austin.

One stands out in his mind – a gifted 12-year-old boy named Raymond Johnson, who would become the first Black student to attend Rice University. Brooks was principal and school counselor at the school in Alice that Raymond attended in the Fifties. It was rough. “To give you an idea,” Brooks said, “The first week [I was there] a girl in one of the classes got up and shot her ex-boyfriend with a pistol.”

Brooks knew Raymond was incredibly bright, but teachers at the school were prejudiced. Over coffee he’d hear adults using the N-word. “I thought Raymond could possibly get a scholarship to college,” Brooks said, but it was an uphill battle. He said there were just two teachers, an English and a math teacher, who weren’t prejudiced. “So I worked with them. I said, this is my objective.”

When Raymond got into Rice University years later, Brooks drove him to Houston. He brought them to a fancy place for dinner to celebrate, though he wasn’t sure they’d allow a Black customer. “I told the host, 'Two please,’ and I had no idea what was gonna happen.” Though they were ultimately seated, he said they got strange looks during the meal. Afterward, he brought Raymond to his dorm at Rice. Brooks said it wasn’t until six months later that he learned two other Rice students had sued to keep Raymond from attending.

Shortly after Raymond attended university, Brooks moved back to Austin, working at his alma mater of Austin High. By 1966, students there “were more sophisticated. They were from a big city. I had to learn to adjust to their social life.”

He remembers a girl who came to him and said, “Mr. Brooks, how can I be popular?” (The answer: Find some clubs she was interested in. Those ended up being French, cooking, and sewing, he recalls.) He eventually took a supervising job that paid better but meant less face-to-face work with kids, and he missed them.

Brooks still lives at his North Austin home, with the support of a beloved volunteer who brings him groceries on a regular basis. And he maintains a busy social calendar.

So what’s the trick to a long life with a clear mind? “I don’t know!” Brooks said. “I just enjoyed people. Like kids, I enjoyed working with kids so much.”

When asked about the best decision he ever made, it doesn’t take long to decide: “To move back to Austin.”

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.