Ricky Smith Tried to Escape Prison Three Times. Is 30 Years In Solitary Confinement Enough?

His last attempt was in 1993

By Brant Bingamon, Fri., March 22, 2024

Ricky Smith has a simple request. He wants to be allowed to reenter general population somewhere in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice prison system, where he’s been held in solitary confinement for over 30 years.

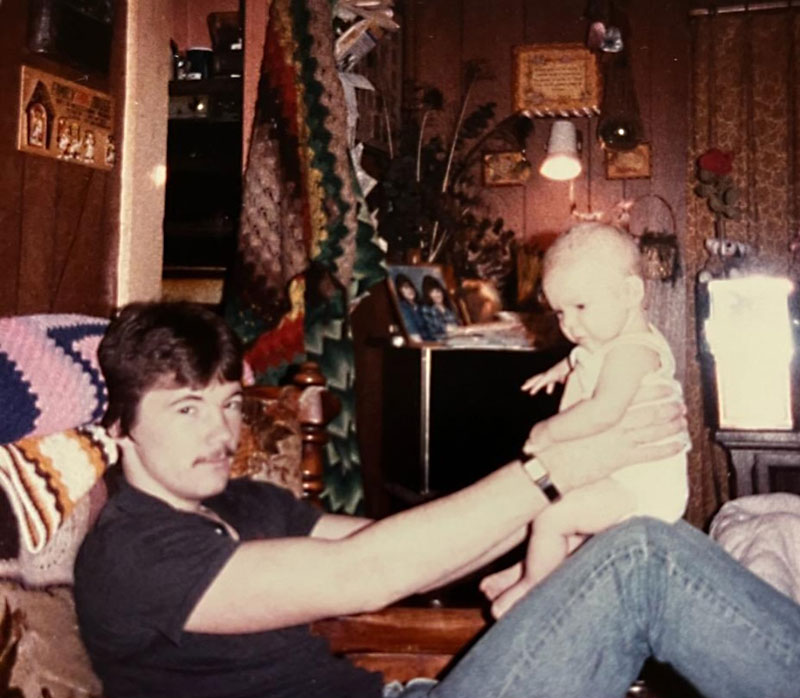

Smith, now 56, has been incarcerated since the age of 19, when he was convicted of assaulting a police officer in Harris County. He has been held in solitary confinement since 1993, after he attempted a series of prison escapes over a five-year period. “I escaped from the Wynne Unit in January of ’88,” Smith told us. “I was scheduled for parole and release that October, but I caught a disciplinary case and lost my good conduct time. I was so angry over it all – I had lost my girl and I was stressed about that – that I went over the gate.”

Smith was sentenced to 35 years for the Wynne escape and then was caught planning an escape from the Walls Unit, receiving an additional 50-year sentence. In May of 1993, he escaped from the Coffield Unit, stealing a truck from the prison parking lot and evading officers in a high-speed chase before being apprehended two days later. Smith received a 99-year sentence for the Coffield escape. He was taken out of general population and placed in a cell by himself, where he is confined for 23 out of 24 hours each day.

This kind of incarceration is usually called solitary confinement. But TDCJ told us it does not practice solitary confinement – they practice “security detention.” According to the department, it reserves security detention for “an inmate who is a current escape risk; threat to the physical safety of other inmates or staff, to include volunteers and contract employees; threat to the order and security of the prison as evidenced by repetitive serious disciplinary violations; or a confirmed member of specific security threat groups.”

Smith said he has had no serious disciplinary cases for 30 years, is not a threat to other inmates, and does not belong to a hate group. He described how he decided to give up his breakouts after the third failed attempt. “I just sat down and reconsidered my whole situation. I was like, 'I’m spinning my wheels – every time I get away something screws up and they find a way to catch me.’ So after ’93, I figured I’d just stay put. I haven’t done anything since then but sit back here, slowly rotting. Right now, the only thing that’s a justification for keeping me here is that I’m an escape risk.”

Smith said that over the years he’s been incarcerated in the same high-security pod as other inmates with escape histories who were eventually released back into general population. The TDCJ reviews his case every six months but has never released him from security detention. Smith told us he’s been denied parole by the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles four times, with the explanation, “The record indicates that the offender has repeatedly committed criminal episodes that indicate a predisposition to commit criminal acts upon release.”

“They keep using that over and over again to justify keeping me here,” Smith said. “There’s no way I can erase that history. And they don’t ask, 'Well, why did it happen? How did it happen?’”

For many years, solitary confinement (called security detention or administrative segregation depending on the year) has been described as a form of torture that can lead to insanity. In 2011, the United Nations recommended a worldwide ban on the practice in most cases, saying it causes mental and physical health problems in a significant percentage of those who experience it. TDCJ seems to understand that the practice should be discouraged. TDCJ spokesperson Amanda Hernandez said the department has reduced the security detention population by 65% in the last 17 years, from 9,180 in 2007 to 3,141 in 2023. At these reduced numbers, approximately one out of every 40 inmates is held alone in a cell about the size of a bathroom for almost the whole day, every day.

Smith told us he has kept his sanity, but the isolation has had its effect. “Humans aren’t really designed for this sort of environment,” he said. “It’s kind of a torture. Just cooped up all day. Can’t do nothing. And then your family members, over the years, they slowly die off. Can’t go to the funeral. My little girl got raised without me. Didn’t really know me.”

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.