How Driving Somebody From One Texas City to Another Can Turn Into a Prison Sentence

Rides from hell, thanks to Texas’ immigration law

By Benton Graham, Fri., Feb. 2, 2024

You recently graduated high school and plan to pursue a secondary degree. The future is a mix of hopefulness and uncertainty. Money is tight for you and your family. As you’re perusing Snapchat, a direct message pops up on your screen: “Me and some friends need to take a ride from one place to the next.” They offer $1,200 and to cover gas costs.

Would you take that deal?

Attorneys told us that is the scenario that many low-income young men of color are facing in Austin, San Antonio, Houston, and other Texas cities. In fact, that message is exactly what popped up on Nathan Perrow’s Snapchat.

“I didn’t think anything of it. I just thought I was going to give them a ride and I was going to get paid,” Perrow told legislators during a House State Affairs Committee hearing in October.

When he arrived at the pickup location in Del Rio on August 21, 2021, he didn’t see anyone. Then the Texas Department of Public Safety trooper’s lights flashed behind him. Despite not having anyone in his car, he was arrested for human smuggling and spent three months in the Briscoe Unit – a Texas state prison. Perrow had just graduated from high school when he was arrested.

Perrow, who said he now attends the trade school Gary Job Corps in San Marcos, had been ensnared by one of the lesser-known claws of Gov. Greg Abbott’s multibillion-dollar immigration crackdown known as Operation Lone Star. Understandably, much of the Operation Lone Star scrutiny revolves around the program’s treatment of migrants. For just one example, last month three migrants died trying to cross the Rio Grande from Piedras Negras, Mexico, into Eagle Pass as state troopers and National Guard troops blocked Border Patrol officers from reaching the group, making national headlines and drawing legal challenges from the Biden administration.

However, the reach of Abbott’s initiative does not end with undocumented migrants. Many Texans, most of whom are U.S. citizens, are staring down felony charges for human smuggling, all without having ever crossed the border. A January press release from Abbott’s office said Operation Lone Star, which launched in March 2021, has resulted in 35,100 felony charges. (The Chronicle requested the Texas DPS provide a breakdown of the types of charges – smuggling, evading arrest, possession of a controlled substance, etc. We had not received a response as of press time.)

Add “human” in front of “smuggling” and the already sinister word conjures up images of the evil depicted in movies like Taken or Sicario. But what is actually happening near the border appears to be more akin to an Uber or Lyft ride. A young person receives a message on Snapchat, TikTok, or WhatsApp to give someone a ride from South Texas to their hometown for hundreds or even thousands of dollars. In dire need of cash, the no-context ride request is tantalizing.

In South Texas, people arrested for “smuggling” are often pulled over for a pretextual stop – something like a broken headlight, forgetting to put on a turn signal, or a minor speeding violation – giving law enforcement officers like the state troopers the opportunity to see if there are any undocumented people in the car.

Some defense attorneys interviewed for this story acknowledged that some of their clients knew they were engaging in an illegal activity, but the attorneys told us the vast majority simply saw it as a fairly easy gig driving someone within the state.

“They assume that smuggling has to do with going over the border or bringing people over the border,” said attorney Sylvia Delgado, who estimates that she has represented around 100 clients charged with smuggling, with quite a few from Austin. “Smuggling, you imagine – what I always imagined – is: I go over the border, I bring back a bunch of gold jewelry or something of value and I don’t want to have to pay a tax on it, so I just wear it and pretend I’ve owned it my whole life.”

Addy Miro, a criminal defense attorney based in Austin, echoed that point. “It’s unfortunate because there’s a lot of people ending up with felony convictions for something that sounds really bad on paper, but when you look at it, it’s just giving somebody a ride from point A to point B, not knowing that what they were doing was wrong.”

Maite Sample, the supervising attorney for the Neighborhood Defender Service’s Operation Lone Star practice, offered an example highlighting how sophisticated the recruitment can be. “I had one client tell me that there’s this reel with this guy kind of showing all his money and all his stuff and said, ‘If you want to know how I make my money, reach out to me,’” she said. “He reaches out and he’s told, ‘Hey, if you go pick up these people, I’ll pay you this much per person when you drop them off at this location.’ But obviously he did not make it back to the location because he was stopped and arrested.”

Those mistakes are set to become even more consequential, as the Texas Legislature passed and Abbott signed Senate Bill 4 during a fall special session that will elevate the minimum sentence for smugglers to 10 years. With the new law set to go into effect on Feb. 6, the Chronicle set out to understand the confusion caused by the previous law, how the harshened penalties figure to change the dynamic, and who is really behind human smuggling in Texas.

The Faces of Smuggling

Back in October, as Perrow wrapped up his testimony, a seemingly dumbfounded Rep. Chris Turner, D-Grand Prairie, prodded the young man’s story further. “I just wanna make sure I understand. You were going to go pick up some people for a fee, they were going to pay you, and you didn’t actually pick anyone up though?” Turner asked.

“No sir,” Perrow responded.

“Do you know how they justify that charge?” Turner asked after Perrow informed he had been charged with six counts of human smuggling.

“Yes, when I was about to pick them up, there was no house or nothing. There was just a big old fence,” he said. “The officers, they jumped the fence, and they found illegals and they said they were just going to put them on me because they thought I was picking them up.”

According to defense attorneys, Perrow’s case seems to be consistent with a pattern of aggressive and sometimes questionable tactics used by law enforcement in the area. Affidavits shared with the Chronicle reveal the extraordinary lengths DPS troopers have gone to arrest potential smugglers.

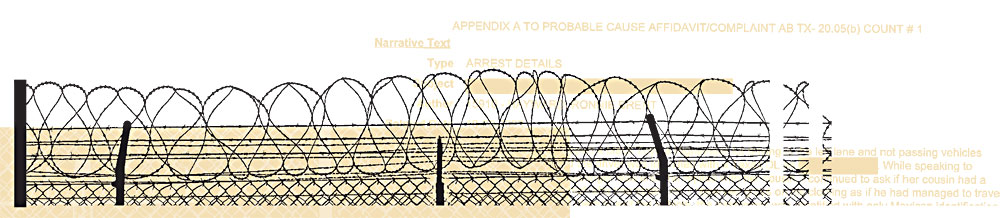

“On 10/20/2023, I, Trooper R. Hayward, stopped a black Toyota Highlander for driving in the left lane and not passing any vehicles in the right lane,” one affidavit reads. “A stop was initiated and the driver was identified with a Texas DL as [REDACTED]. While speaking to the [REDACTED], I asked her who her male passenger was and she replied with her cousin. I continued to ask if her cousin had a license or any form of identification to which she stated no. I observed grass on his clothes as if he had managed to travel through the brush of the area and asked them to exit the vehicle. The passenger was identified with only Mexican identification. [REDACTED] admitted to picking him up since she was in the area to look at washers and dryers off of Facebook Marketplace.”

In another affidavit, a state trooper states that he pulled a man over for what he thought were illegally tinted windows. After a check, the trooper determined that the tint was legal. However, before he checked the tint, he learned that the driver did not have a driver’s license. As he spoke to the driver, he wrote that he began to smell an odor coming from the car.

“Through my training and experience alongside Border Patrol, I identified the smell as an odor that is associated with human smuggling,” the affidavit reads. “Undocumented aliens emit a distinct odor due to sweat and being exposed to the environment.” The driver then declined the state trooper’s request to search the car, so the state trooper called in the local K-9 unit. “The K-9 alerted and a probable cause search of the vehicle was conducted. Two male subjects were in the trunk of the vehicle and were identified as illegal immigrants.” The driver was arrested and the two undocumented men were transferred to Border Patrol’s custody.

Multiple attorneys defending smuggling clients described this type of arrest as common: a series of seemingly minor events – driving in the right lane, a grass stain, and a lack of identification – that give state troopers the opportunity to arrest someone for a felony.

“You look like you’ve got brown people in your car, I’m going to follow you until I see you violate the law, a traffic law of some sort so that I can pull you over, which is allowed,” said Angelica Cogliano, an Austin-based criminal defense attorney who is partners with Miro at Cogliano and Miro. She said that one of her clients, who is Cuban but living in Austin legally, was pulled over while driving a friend who was also here legally.

“They were driving down south actually to meet some girl they met on Tinder, but because he was driving a Mercedes and he was Black, and he was on a road that a Border Patrol stop is not on, they suspected him both of stealing the car, which was registered to him, and smuggling somebody,” Cogliano said. “He went to jail and his passenger went to immigration and then they were both released, right? Because they were both here legally, they weren’t transporting anybody. They weren’t hiding from law enforcement. They just were Black and didn’t speak English.”

Indeed, this is a trend that defense attorneys consistently mentioned. “We’ve been literally seeing probable cause statements that mention it was a Hispanic male driving, and it’s like part of the discussion of why the person was pulled over,” said Doug Keller, legal director at Lone Star Defenders Office. Prosecutors in Val Verde County, where many of the smuggling cases are being handled, did not respond to the Chronicle’s inquiries for this story.

Police State

The immense police presence in some border communities is hard to miss. Several attorneys and community organizers referred to the South Texas towns like Eagle Pass as a “police state.” On a visit, it didn’t take long for this reporter to confirm that assertion. Having just crossed into Maverick County around 8:30am, I saw a DPS trooper pulling over a car on the highway, which represented just the beginning of my encounters with law enforcement.

Amerika Garcia Grewal, a member of Border Vigil Eagle Pass, a community group that advocates for a compassionate approach to immigration issues, has seen her hometown subsumed by Operation Lone Star. The presence of the media and police is inescapable. Garcia Grewal pointed to the various SUV tops to show which color represented which agency: SUVs with lighter tops were Florida law enforcement and the all-black SUVs were Texas state troopers. Plain white SUVs tended to mean media, she said.

Garcia Grewal and her family started to notice the police presence sometime before 2022 when her dad dropped her mom off at the Monday flea market and went to walk their dog at Shelby Park – a part of their typical routine. “DPS came up to him and said, ‘You can’t be here,’” she said. “He’s like, ‘Why?’... So they’re like, ‘This is for Operation Lone Star, you can’t be here.’”

Only three weeks prior to my visit, the Border Vigil Eagle Pass had erected 700 crosses in Shelby Park to represent people who died trying to cross the border. She said the concertina wire strung up as a result of Operation Lone Star has only made the journey for migrants more perilous. “What’s so frustrating is that the cruelty is the point, and we can have border safety without cruelty.”

When Garcia Grewal attempted to show me the shrine she had helped set up, a young Texas DPS officer told her we wouldn’t be able to access it and breathed a halfhearted apology into the dust-filled wind. As we moved farther along the park’s perimeter, another trooper, only this time from Florida, came to intercept us. He pointed to the top of a hill where a news crew was set up, and told us that was as close as we could get to the river. We approached the videographer on the hill, whose camera continuously rolled as he shielded himself from the wind inside his car. The crew was from Fox, and he gruffly told me this has been his job for two years.

Just three days after my visit, Texas took the drastic step to close off Shelby Park to federal agencies, leading to the three migrants’ deaths in January.

Gage Brown, an organizer with the Border Organization, said many in her hometown of Brackettville support Operation Lone Star, but the community is increasingly fed up with high-speed chases. The Operation Lone Star program led to crashes that killed 74 people and injured at least another 189 in a 29-month period, according to an analysis by Human Rights Watch published in November. “It’s usually every day there’s a chase, and then we have helicopters flying overhead,” Brown said, adding that the intense policing of the roads has even made some people in the community stop driving altogether.

From Bad to Worse

From the perspective of attorneys, the approach to cracking down on smuggling resembles the War on Drugs’ crackdown on low-level drug offenders, rather than the leadership of those operations. Miro noted seemingly low interest in pursuing whoever sends the initial social media message to recruit the drivers, even though many of her clients have expressed openness to cooperating with efforts to track down recruiters.

Defense attorney Delgado personally believes the border is too open and that Biden is failing Texas, but she said the smuggling law is far too vague. “The first time I ever saw this law, I thought, ‘Wow, that’s terribly written,’” Delgado said. She added that only about five of her clients consciously knew they were doing something illegal.

“Let’s just say my female friend is getting beat up by her boyfriend. If she’s like, get me out of here, I just want to go and hide. If you’re concealing them from police officers, from somebody, if they’re hiding themselves, I can get charged with smuggling,” she added. On the flipside, Delgado said many of her clients aren’t even concealing their passengers, who are often riding in plain sight, not hidden under blankets or in luggage.

As long as the smuggling laws are on the books, some attorneys would like to see a greater effort to make the public aware of their existence. “All this money that is going into [Operation Lone Star], it’s a lot of money, and none of it to my knowledge has been allocated to just alerting people, ‘Hey, if it sounds too good to be true, it is. Do not engage in this. If somebody tells you on Facebook, I’m gonna give you money to do this, just don’t do it,’” Miro said. Along those lines, Garcia Grewal said she would like to see workshops for Latino youth to help avoid harassment from law enforcement, including the kind of lessons parents of color teach children about “driving while Black.”

With the explosion of human smuggling cases being a fairly new phenomenon in Texas, many of the attorneys are still trying to understand how cases will play out under the old version of the law. Thus far, only two cases have gone to trial. Currently most clients are either getting probation or deferred adjudication probation (which means the case can eventually be dismissed). But with the newly passed legislation and the harsher sentences that come with it, that could change.

Keller admitted that it’s hard to know the exact effect of the law, but he said it’s very harsh. “It’s gonna make it difficult to process a lot of these cases from the state’s point of view because, at the end of the day, when they have these really ridiculously harsh sentences, a lot more clients are gonna want to go to the trial because people don’t want to sign a piece of paper agreeing to serve 10 years,” Keller said. He added that the state will likely wind up spending a lot of money on the cases.

Not only will smuggling sentences harshen, but another law is set to take effect in March that makes it a state crime to cross from Mexico into Texas illegally. Since immigration is in the federal government’s purview, this raises the question: Will the federal government throw more weight into fighting Operation Lone Star?

Overall, advocates believe Operation Lone Star is about scaring migrants away from the U.S. and instilling fear in border communities, said Carolina Canizales, senior Texas strategist with the Immigrant Legal Resource Center.

Because of that, she has spearheaded a Travel Advisory Map, where people can look up the commitments a county has made to Operation Lone Star efforts and plan for safer travel. For example, Val Verde County has one of the highest risk ratings, because it has a jail and processing center dedicated to people arrested for Operation Lone Star-related charges, as well as two Customs and Border Protection interior checkpoints.

Perrow, the man arrested for human smuggling who testified before the House State Affairs Committee, confirmed the sense of fear that Canizales called out. “The interactions with the officers were terrifying. They were asking each other, ‘Where should we take him?’” Perrow told the committee. “After they spent some time talking, they decided on their decision. I spent three months in Briscoe Unit, and I lost my opportunity to join the National Guard.” The irony: Had Perrow not been arrested for human smuggling despite transporting zero people, the state could have had another recruit to carry out its Operation Lone Star enforcement efforts.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.