Once Again, Redistricting Looms in Texas

Republicans hold all the power to draw new lines, but there's more attention on the process than ever before

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., Feb. 12, 2021

Who's your congressperson? Here in Austin we have six to choose from, a real variety pack. It could, sadly, be someone who voted to overturn the 2020 presidential election, a position backed by literally dozens of Austinites. Even the two very conservative reps from Travis County – Michael McCaul and Chip Roy – thought that was crazy talk. But still, at least 250,000 of us are "represented" in the People's House by John Carter, Pete Sessions, and Roger Williams, older white gentlemen from beyond our frontiers who chose MAGA insurrection over a peaceful transfer of power. That's why redistricting matters.

Austin has been America's tragic poster child for the depredations of gerrymandering for two decades now, ever since Tom DeLay – remember him? Dancing With the Stars? – ventured rogue to re-redistrict Texas in 2003, after the GOP flipped the state House and gained complete control of state government. That Legislature went into double overtime after Democrats in both chambers fled the state to break quorum; it was all very dramatic. Back then, we were mad that Austin was split into three congressional districts, which met at the old Marimont cafeteria on 38th Street near Guadalupe. Come the next cycle in 2011, as Austin continued to swell and the GOP got used to taking no prisoners, we got carved into six pieces, five of them held by Republicans. The one Democrat, and the only one whose tenure predates these antics, is Austin native Lloyd Doggett, who's spent 14 terms serving ever-shrinking pieces of his hometown through five different maps; the current one chains together clusters of mostly Latinx constituents from 23 different cities from here to the Alamo. (Doggett, not San Antonio's favorite son Joaquin Castro, represents the Alamo itself.) Meanwhile, our City Council includes one Republican and 10 Democrats; Travis County's entire government is blue, down to the constables; and nine Dems and no Rs represent parts of Austin in the Texas House.

Ten years on, Republicans in the 87th Texas Legislature again hold all the power to draw new lines, having held off a Bluenami last November with the aid of these skewed maps. (As Julie Oliver, the Dems' 2020 nominee to unseat Williams, said on election night, "Gerrymandering sucks.") The numbers needed to draw those new lines would, in a normal cycle, have already arrived at the Capitol, but the 2020 census, nearly broken outright by COVID-19, corruption, and lies, won't deliver its redistricting data until after the Legislature adjourns sine die May 31. While a special session this summer is widely expected, the long delay is one of the forces that exposes this round of redistricting to maximum potential mischief.

After the Dummymander

If the GOP has already rigged the game with unfair maps, why were Texas Dems so optimistic about flipping the House? Why did national Dems spend so freely to unseat McCaul, Roy, and Williams, and to claim three other open Texas seats? As you know because you live here and are sentient, the state is Growing and Changing, becoming much more urban and in the process somewhat more like Austin; we're no longer a complete outlier in Texas politics.

It's common for politicos, particularly those out of power, to wring their hands about the unfairness and injustice of this all, and how redistricting should allow voters to choose their reps and not the other way around. It's obviously true that gerrymandering has left many people without the voice they're supposed to have in representative government; nobody in Austin thinks Roger Williams, a car dealer from Weatherford, speaks for them and understands their issues, even if they're conservative. But the demographic sorting of the parties, and the geographic sorting of those demographics, happens in real life, not just in the Sims-like realm of map-building software.

For a local example, Austin's inner-ring suburbs – Cedar Park and Round Rock in Williamson County, Buda and Kyle in Hays County – have turned blue because Dem-leaning voters have moved to those places. In the 2011 map, a new Texas House district was drawn around Cedar Park – you can tell it was squeezed in at the last minute, because it's numbered out of sequence, House District 136 – and was seen as naturally friendly terrain for WilCo conservatives like Tony Dale, a Cedar Park City Council member who won the seat easily. By 2018, the guy whom Dale defeated, current state Rep. John Bucy III, was able to flip the script and win by 10 points, and then hold on for a fairly easy reelect in 2020. The voters whom the GOP picked out for Dale are now found farther afield in WilCo's exurbs – Leander, Liberty Hill, and emerging master-planned communities like Santa Rita Ranch.

That makes the 2011 map, in the parlance of election geeks, a "dummymander" – highly engineered lines that no longer match facts on the ground as populations shift across them. Despite the mythic American ideal of the open-minded swing voter, these demographic changes have a bigger impact than actual shifts in voters' party preferences. Looking forward, "when you look at the demographic trends in Texas, [Republicans] have to gerrymander more than they even had to before, because there's nothing happening with the state's growth that makes it easier for them to achieve their goals," says Fred Gifford, the director of geospatial analytics – i.e., "the map guy" – for the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, also known as All on the Line.

The party in power's goals include not just winning seats but protecting its incumbents. Even with its brutally one-sided maps, 2018 and 2020 forced Texas Republicans into hand-to-hand combat; while the Dems couldn't back up their Bluenami trash talk last year, the GOP has made no gains in either Congress or the Lege since 2014, a truly poor performance compared to other states. Many Texas seats – especially in the urban areas that form the "Texas triangle," and most especially at Austin's corner of that triangle – are now bloated with new voters, well above their intended size, whose partisan leanings are ambiguous, which confounded and disappointed both parties last November.

Those lines will need lots of redrawing to equalize district populations and uphold the constitutional principle of "one person, one vote," but in the view of Gifford and other expert observers, it will be nearly impossible for the GOP to create fair maps that reflect Texas' demographic trajectory while also keeping its incumbents safe. For the state offices – the Lege, the State Board of Education, and the state appellate courts – the number of districts will not change, although a storm is brewing over those appeals courts. (There are 14, seven controlled by each party, after four of them – anchored in Austin, Dallas, and Houston – flipped blue in 2018. Rumor portends a GOP attempt to consolidate the 14 into fewer, redder districts.)

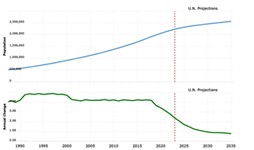

It's also true for the congressional map, which will gain at least two and probably three new seats at the expense of slower-growing states, and where precedent demands that the districts be as nearly equal in population as possible. For all the maps, assuming the 2020 census data is not completely off base, the direction should be clear – more seats in the urban Texas triangle and more seats that lean Democratic, given Texas' profound partisan polarization along racial and ethnic lines. "Almost 90% of Texas population growth in the last decade was not white," says Michael Li of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University, a Texas native whose report on the national redistricting landscape for this cycle was released this week. "So a good argument can be made that all three new [congressional] seats should be opportunity districts" – meaning ones tailored to allow Black and brown voters to elect the candidates of their choice, in keeping with what remains of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The Letter of the Law

Li is focused on the legal endgame that has, for every single cycle since the VRA was passed, accompanied Texas redistricting, both when it was controlled by Democrats before 2003 and in the years since. The delay in the census data – and the likelihood of needing a hurried special session to get the maps done in time for candidates to file for the 2022 primaries this December – "is just a recipe for mischief," Li says. "The rules are looser, and the governor controls the timing of a special session, and now that you don't have to get the maps pre-cleared [by the U.S. Department of Justice], there's a lot of gaming potential. They can push it right to the very end, which creates a huge potential for abuse."

In 2011, for the first time, the DOJ's interests (under President Obama) lined up with the plaintiffs who sued to challenge the maps, and not with the state of Texas. The 2012 primaries were delayed to allow time for an interim set of maps to be cobbled together while the Lege's ill intentions and unignorable racial bias got laid out in court. (That delay allowed little-known GOP operative Ted Cruz to catch up with and then blow past Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst in the primary for the U.S. Senate seat he now holds.) But in 2013, in Shelby County v. Holder, the U.S. Supreme Court knocked the props out from under the VRA's preclearance provisions, preparing the way for the blatant voter suppression seen across MAGA-merica today, abetted rather than combated since 2017 by the Trump DOJ. (The plaintiff county is in Alabama, home to affluent white Birmingham suburbs.)

To be clear, the VRA is still in effect, and unjust racial gerrymanders are still illegal, but they can no longer be thwarted before the maps go into effect. When a state like Texas opens up the throttle against Democrats, it will harm minority voters in nearly every instance, so advocates for both Democratic party groups and Black and Latinx voters expect to drop lawsuits against any plans that preserve the GOP imbalance and protect the incumbents from the 2011 and 2003 cycles. But any plan that doesn't do those things – that reflects non-Anglo, Democratic-leaning population growth – will not pass this Texas Legislature.

Help may be on the way from the new Biden DOJ helmed by Attorney General Merrick Garland, and maybe even passage of pro-democracy legislation – the For the People Act or the updated John Lewis Voting Rights Act – by a de-filibustered U.S. Senate. But all parties will be racing against the clock. "As soon as the data comes out, the current maps will be unconstitutional," says Li. "Somebody will have to draw maps – either the Legislature or the courts – for 2022" if the redistricting special session, or sessions, don't happen or go pear-shaped.

For the state offices, there is a possibility that the ad hoc Legislative Redistricting Board – five members of state leadership, all Republicans – will convene, spit out some maps, and bumrush the entire public process, but that's not an option for the congressional map, and even Republicans don't trust each other enough right now to see that route as preferable. As redrawing the Lege's own maps will involve, out of necessity, transferring seats now held by exurban and rural Republicans into the metro counties, incumbents are anxious, and as the normal spats and tumbles occur this session, everyone is watching out for knives aimed at their backs.

All of which means that, delay or no, people are not sitting around waiting to see what happens. "People absolutely know where the population has grown, where the demographics have changed, and have an idea of what they want to do," says Li. "You now have tools that allow you to generate hundreds, if not thousands, of maps; they're already looking at the options."

Building the Record

Late last month, two weeks after the 87th Lege gaveled in, the Senate Special Committee on Redistricting, chaired by state Sen. Joan Huffman, R-Houston, and including 17 of the chamber's 31 members, decided there was no time like the present to start holding hearings. No data? No problem! The House hadn't named its redistricting committee yet? They'll catch up! Nobody knows how to hold a virtual hearing and receive testimony under the Lege's new, awkward COVID-19 protocols? Someone's gotta go first!

This matters because the hearing testimony, and then the debate to be held on each set of maps on the House and Senate floor at the end of our redistricting journey, are the only guaranteed venues for the will of the people to be entered into the legislative record, and thus into the inevitable litigation that will follow. "That's proving to be exactly what's necessary," says state Sen. Sarah Eckhardt. "We" – by which she means both us, the people, and her like-minded fellow legislators in both chambers – "need to ask a lot of questions, bring lots and lots of statistics and data to the floor, and get answers from those legislators who will be making these decisions so that we can get their intentions on the record."

The House and Senate redistricting committees may technically meet in public in between, but never have they ever haggled over boundary lines in a place where we could see them. In 2011, GOP members did not even share draft maps with their Democratic colleagues on the committees. "I was chairing the [Senate] Democratic caucus then," said Eckhardt's predecessor Kirk Watson, now dean of the Hobby School of Public Affairs at the University of Houston, speaking at an All on the Line training held last weekend. "I remember camping outside the door of the committee room with my chief of staff, demanding to get to see what the maps look like. Redistricting, and I'll just say [this] as plainly as I know how, is driven by craven politics. It is purely, simply, and completely about politics right now, not about creating a representative government."

In the wake of the sloppiness and sleaze of 2011, Austin voters the following year finally amended our city charter to create the 10-1 district council, after decades of electing everyone at large. Many who were skeptical of single-member districts wanted to see the lines on the map before they decided, which was not possible; instead, 10-1 backers crafted a redistricting process that inverts all the Lege's shenanigans, anchored by an Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission. This cycle's incarnation of the ICRC met for the first time this week.

Creating an independent commission to depolarize redistricting at the state level, as is the case now in some form in 10 states including California, is an avowed policy goal of many in Texas. It's also supported by All on the Line, which was founded by Obama A.G. Eric Holder (the losing party in Shelby) to raise awareness and engagement around redistricting among Democrats on all fronts. This includes getting engaged in defending the integrity of the census, supporting drives like the 2020 push to flip the Texas House that would give Dems more control of offices (governors, legislators, elected judges) that have a hand in redistricting, and evaluating proposed maps for fairness (that's the job of Fred Gifford's team).

Since the Dems were not very successful in any state in 2020 in gaining more power over redistricting, All on the Line is also gearing up for legal warfare that will be a lot more visible this time around, now that "election integrity" is such a hot topic for so many people who define it in such drastically different ways. As Eckhardt notes, getting up into the Lege's face right now is essential to that strategy. "Constituencies that are concerned about being disenfranchised need to get involved with the organizations in the coalition to draw fair maps," she says; those include, in addition to All on the Line, such groups as Common Cause, the League of Women Voters, and advocates for Black and Latinx communities. "And tell their legislators, 'This is who I think my community of interest is, and it's far more important than what you, as an elected official, want to do just to try and hold on to your seat.'"

All on the Line's Texas director is Gen Van Cleve, a longtime advisor to Eckhardt and also the past political director of Annie's List. "I've done a ton of campaigns in Texas, and what I can tell you is that the fundamentals of redistricting are broken," she told her volunteers at the training that also featured Watson. "And just like in a basketball game, you cannot win without the fundamentals. It is incumbent upon the public to pay close attention to the issue and really take back this process, and shine a very bright light on it."

Van Cleve is of course frustrated by the process – having, for example, to hurriedly train up volunteers to testify in Huffmann's pop-up hearings – but, like many people, committed now more than ever to seeing it through to the finish line. "We will not be immediately successful and get exactly what we want everywhere," she says. "But it gets harder and harder to do the kinds of things that past redistricting committees have done if there's a constant drumbeat, not just by people interested in redistricting but also advocates for reproductive justice, for clean energy, for every particular issue. It has to be in the mouths of every single one of us."

The Senate Select Committee on Redistricting holds its remaining hearings on Feb. 12, 19, 26, and 27. You can testify at any hearing, though all but the last have a specific regional focus; Austin takes center stage on Feb. 26. (These would have been held throughout the state but for COVID-19.) Witness instructions are available at the Texas Legislative Council’s redistricting portal: redistricting.capitol.texas.gov.

“All on the Line” events and trainings are on the Mobilize platform used by many Democratic groups: www.mobilize.us/allontheline.

Wow, Our Map Sucks! How Could It Be Fixed?

Map A: What We Have Now

Travis County is, in the words of state Sen. Sarah Eckhardt, "the poster child of the poster child" for bad gerrymandering, bad even for Texas. In 2011, Republicans managed to add four new U.S. districts to the Texas map and still deprive Democratic-leaning Black and Latinx voters of chances to pick the candidates of their choice. Technically, Congressional District 35 was an "open" seat with a Latinx majority, though most of its constituents were then, and are now, represented by Lloyd Doggett. To support this fiction, Central East Austin, where Doggett owns a home, was bizarrely drawn into the new CD 25, represented by Roger Williams. That's one way Austin got split six ways in this 2011 map. Another, carried over from 2003, was the petty desire that then-Rep. Lamar Smith, chair of the House science and technology committee, represent the UT campus (in CD 21), even though he lived in San Antonio.

Map B: MALC's Alternative

The Mexican American Legislative Caucus, as a lead plaintiff against that map, offered several alternatives; this one simply split Austin at the river between Doggett and Michael McCaul (CD 10), forced Smith out of town, reclaimed the Williamson County bit of Austin (which is now much larger) from John Carter (CD 31), and crafted CD 35 to include San Marcos and the Texas State campus.

Map C: Maximized Compactness

Those plaintiffs' maps are still "gerrymandered" to maximize minority opportunities; any "fair map," such as would be drawn by an apolitical commission, needs to balance multiple criteria such as "compactness," which is what forecloses the weird boundaries and shapes that people associate with gerrymandering. A Central Texas map maximized for compactness, from the oddly named but quite authoritative site Dave's Redistricting, delivers a tight east-of-MoPac district (likely also a Black/Latinx opportunity district) to be represented by Doggett and his Democratic successors until the apocalypse, and a Westside district that also covers the bluer parts of Williamson and Hays counties.

Map D: Packing the Dems

Something like this is more likely to emerge from the 2021 cycle than the current six-way split, in the view of observers of both parties, as metro Austin's endless growth will only further imperil its GOP reps without another Democratic "vote sink" anchored in Travis County. We drew this map, based on 2018 data and including 39 districts statewide (a gain of three), to show how this might be done while also leaving McCaul, Chip Roy (Smith's successor in CD 21), and Carter out of harm's way. McCaul lives in West Lake Hills, so CD 10, which stretches to Houston, has to sneak up around the Southside to make this work. Doggett's seat would for the first time in 20 years be contained entirely within Travis County, and a new seat would take in the rest of Travis, the blue burbs in WilCo and Hays, and Bastrop and Giddings; the dataset suggests that a Democrat would have an 8- to 10-point advantage in this seat.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.