A Long Activist Legacy Survives on the Eastside

Holding on to El Barrio

By Brant Bingamon, Fri., Nov. 20, 2020

It’s a bright afternoon on Indigenous Peoples Day, and Bertha Rendón Delgado is interviewing her elders in the shade of a pecan tree in Chicano Park. The interviewees arrive single or in small groups, and Delgado motions them to a folding chair. Her videographer signals his readiness. She asks questions. “What is your earliest memory of Chicano Park?” “What does Chicano Park mean to you?” “What is your biggest fear of what might happen to this place?”

The oral history project is a small piece of Delgado's work as the chair of the planning team for the park, the formal name of which is Edward Rendón Sr. Metro Park at Festival Beach. It honors Delgado's grandfather, part of a generation of Mexican American Austinites who claimed this crescent of lakefront land as their own. Those who have followed have struggled to hold it ever since.

Delgado is one of them. With her large sunglasses and long flowing hair, she's more fashionable than the average community organizer. But she fits the profile well in other respects, particularly her inability to sit still. In recent years, she's tried to stop the closure of the area's schools with Save East Austin Schools PAC, struggled to preserve the Eastside's many murals as CEO of Arte Texas, and mounted protests for Mike Ramos, Javier Ambler, and Vanessa Guillen. She began her work for the community in 2012, when she was elected president of the East Town Lake Neighborhood Association.

"I remember when they all voted me in, it was at my grandfather's table," Delgado said. "And I was honored because I had all of these elders – my grandfather, my mother, former [Travis County] Commissioner Marcos de Leon, Paul [Hernandez], Frances Martinez ... When I got sworn in as president, they were like, 'This is your first assignment: You're going to go save the parque.'"

Hernandez, the venerable Eastside activist who recently passed away at the age of 74, was Delgado's godfather and mentor. He was of special importance to her that day. "I remember Paul being like, 'You are going to get up there and you're going to do great. You can speak for us. You're going to be the first Chicana out of our concilio to really take the torch.'"

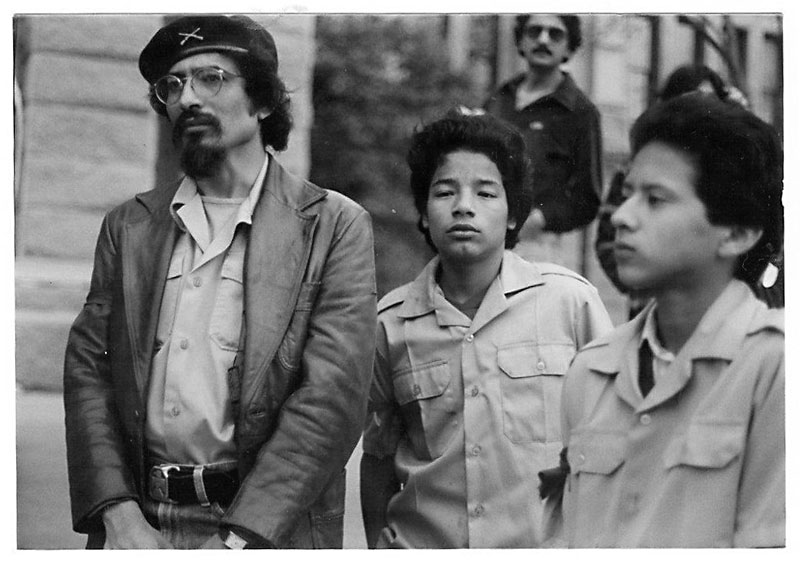

The Brown Berets

Lately, the memory of Hernandez has been Delgado's constant companion. In the Seventies and Eighties, Hernandez led the Austin Brown Berets, a group of Eastside residents in their early 20s who embraced a militant radical philosophy. These were the sons and daughters of working-class laborers, poor people, many of them migrant workers, the victims of racism all their lives. They shocked those on the other side of I-35 with their khaki uniforms and berets, reminiscent of Che Guevara, and their open challenge to white supremacy.

Hernandez is often credited with starting the group, but its founder was Gilbert Rivera. Like most of his peers, Rivera grew up in the Fifties in East Austin on a dirt road with no streetlights, where septic tanks and outhouses served the neighborhood homes. He attended schools that were over 95% Mexican American, where students weren't allowed to speak their first language, Spanish.

"If you were heard speaking Spanish they would report you to the teacher," Rivera said. "The teacher would then either punish you or they would send you to the principal's office, where he or she would also punish you." Rivera was paddled so hard on one occasion that his backside was covered with bluish welts. He didn't speak at all in school for two years thereafter. "Those were the beginning embers of activism," he said. "Even as a young kid you could see that there were issues going on."

After graduating from high school, Rivera became friends with members of the Mexican American Youth Organization, an activist group on the UT campus. "We began to hear about Black and brown kids being abused by the Austin Police Department," he said. "We were definitely being targeted. One night I happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time and got severely beaten."

Rivera had attended a fundraiser for MAYO in January 1973 at a nightclub in North Austin. As the night wound down, police surrounded the club. When he walked outdoors, two officers grabbed Rivera and held his arms. A third pulled his head back and broke his nose with a nightstick. A small riot erupted; a dozen young Mexican Americans were thrown into the police vehicles. After arriving at the police station, Rivera was beaten unconscious and dragged to a cell. When he revived he was beaten again for spitting blood in an officer's face.

The brutality Rivera suffered that night was common on the Eastside. Police beatings of Black and brown citizens had been part of Austin's culture for decades and increased as young people became politically restive in the Sixties. "We were being beaten, our families were getting killed, we saw friends being sent to prison for 50 years for having two or three joints in their pocket," Rivera said.

After his release from jail, Rivera attended a community meeting at St. Julia Catholic Church organized by Father Joe Znotas, a priest beloved by the Mexican American community. Znotas was a proponent of liberation theology, which preached support for the poor and liberation for the oppressed.

"Out of that we began to organize what ultimately became the Brown Berets," Rivera said. "And the Brown Berets came about to serve and protect the community. We started with four white people. Then we recruited more people, people from the university started coming in, people were coming forward from the neighborhood, and many of them were still in high school." Hernandez and Susana Almanza were two of these early recruits.

After the raid on the MAYO fundraiser, Rivera had been charged with resisting arrest, assaulting a police officer, public intoxication, and other offenses. Eleven more defendants faced charges as well. After winning his case and threatening a civil rights lawsuit, Rivera cut a deal with city officials to drop the charges on the remaining defendants.

Rivera then found himself a special target of Austin police. His wife, Jane, takes up the story: "After the settlement agreement, every time Gilbert would leave the house to go see a friend, go to the grocery store, especially if it was in the evening, he'd be stopped by the police. And they'd be harassing him, trying to get him to get into a fight. And he knew what was going on. So he refused to fight, he just took whatever they doled out. But whenever he'd get home he'd tell his dad about it. And his dad said, 'Mijo, you have got to get out of town – they're going to kill you. If you don't leave, they're going to kill you.'"

Rivera believed his father. He made plans to travel to Seattle to pursue his education. "I had recruited Paul less than a year after the Brown Berets started," Rivera said. "And when I was leaving town he told me, 'You're leaving us without a leader.' And I had gotten really close to him, to the point that he had become my daughter's godfather. And I told him, 'You know what? You're gonna be the new leader.'"

El Centro Chicano

Like Rivera, Hernandez couldn't accept the racism he'd grown up with. "Of course he was very charismatic. Very intelligent," said Zeke Romo, a journalist who began covering the Brown Berets in 1973 for the Eastside newspaper The Echo. "I mean, he was a visionary. He thought years ahead of time on what was coming to the Eastside, what was going to happen."

When Romo began covering him, Hernandez was 27 years old and knew the route his life would take. He'd been inspired by the barrio's participation in a strike in the late Sixties against Economy Furniture, a company that exploited Mexican American workers. He'd been mentored by Znotas, who'd introduced Hernandez to Rules for Radicals by Saul Alinsky and A Theology of Liberation by Gustavo Gutiérrez Merino.

These books gave Hernandez the practical and philosophical underpinnings for the protests he would soon mount. They were like nothing he'd read before. "We had to do our own teaching," Rivera said. "We had to start our own schools, if you will. We read Marx, we read Martin Luther King, we read the Constitution, we read the writings of Jefferson. We read as much as we could and absorbed as much as we could."

In the spirit of communal learning, the Brown Berets rented a small house on San Marcos Street, just east of the highway, and named it El Centro Chicano. From there, they coordinated protests against police brutality; demonstrations to bring street lighting, sidewalks, and health clinics to the barrio; and campaigns to get the first Mexican Americans elected to local offices.

In the midst of the work, children from nearby schools began to drop by after class. El Centro Chicano became a de facto afterschool program. "Young kids from the neighborhood, who were basically latch-key kids, started coming and hanging around the headquarters," Rivera remembers. "And we said, 'What are we going to do with all of these kids?' And we had a friend in the Black Panthers, who were here in Austin at the time, and they had a center where they did child care, they had food for the kids, they helped them with their schooling and so forth. So we sort of followed their lead and did many of the same things."

When the children's parents came looking for their kids and found El Centro Chicano, they began to volunteer. The Brown Berets coordinated help for them as well. "They became social workers," Delgado said. "They were able to help people with Social Security services, where food banks were, Medicaid, food stamps. I mean, they became even like attorneys. Legal assistance."

Delgado remembers the community's young organizers – who were referred to as "thugs" across the highway – as an active presence at Metz Elementary when she attended the school in the Eighties. "I would tell my abuela and abuelo, 'Paul was at school today.' And they would be like, 'He's there to talk with the principal and make changes.'"

Hernandez and other leaders arranged for Cesar Chavez to speak to the schoolchildren. "They made that happen," Delgado said. "As Cesar Chavez was marching across the states for justice, for migrant workers, better wages, they coordinated for him to stay here at Martin Junior High. My grandmother made 200 tacos to feed the workers. I mean, I look back at that and I'm like, 'Oh my god! We are so blessed and we don't even know the jewels that we have!'"

Paul's Beatings

The best-known photo of Paul Hernandez is from a protest against the Austin Aqua Festival boat races in 1978. Hernandez is standing in the grass of Chicano Park, in the center of the frame, his arms held back by a pair of police, his thin torso thrust against the fabric of his leisure suit, his legs bent as he seems to sink down. Two more police stand to his left and right, one a uniformed cop, the other an undercover, gripping a nightstick. Behind Hernandez's shoulder is Znotas in his black clerical suit, his lips pressed together, a hand on his chest holding him back. Hernandez's face is pointed down; he seems to grit his teeth or smile.

In those days, Chicano Park was still known to the rest of Austin as Festival Beach, and Aqua Fest – now defunct, but back then a major civic celebration spearheaded mostly by white Westside socialites – sponsored nationally televised speedboat races on Town Lake. The races drew tens of thousands of white spectators who used the neighborhood as a parking lot. In a documentary titled Boats in the Barrio, Hernandez described the community's objections to the races: "Noise, pollution, traffic, thousands of tourists invading a residential area and leaving trash behind, the roar of the motors of the boats – those are the obvious reasons we oppose it. They don't give a damn about our property, our houses, our neighborhood ... and they have the protection of the police."

Hernandez had a deeper reason for wanting the races to end, however. He believed they drove down the value of the lakefront land and caused people to move away, facilitating the displacement that in later years would lead to gentrification. "The developers' interest is this is prime land," he told interviewer Barbara Enlow. "So what you do is, you force people out, buy the property, keep it, and don't encourage any more homebuilding. And at some point, everybody's going to move out. And at that point you develop it."

Eastside citizens had asked the City Council to move the boat races for years. When it again refused in 1978, the Brown Berets mounted a peaceful protest adapted from the teachings of Saul Alinsky. The group maneuvered old, beat-up cars onto the only road leading to Festival Beach and stalled them, backing up traffic. Other protesters shut down I-35.

The police responded by breaking up the protest, pulling demonstrators into the street where they brutally arrested them. Susana Almanza remembers the beating the police gave to Hernandez. "He was hit over the head with the billy club over and over and knocked down to the ground. And they were still beating him. We were all screaming, some of us were crying, because it was so brutal." After the negative publicity generated by the protest, the City Council finally ended the races.

Five years later, Hernandez was again beaten by police, when the Ku Klux Klan marched down Congress Avenue in February of 1983. The Brown Berets, the Black Citizens Task Force, and others had filled the old council chambers to plead that the permit for the event be denied, to no avail. On the day of the march, 400 law enforcement officers surrounded 70 Klan members, protecting them from a chanting crowd throwing rocks, bottles, and sticks.

As the Klan finished the march and retreated to their cars, Hernandez, his then-girlfriend Adela Mancias, and their colleague María Limón found themselves hemmed against the side of a building by a row of 40-50 police. Footage captured from a rooftop and available in a video entitled "The Day the Klan Marched" shows a sudden jostling between Hernandez and an APD officer. Immediately, a dozen police close in a semicircle around him, Mancias, and Limón. Officers begin swinging their clubs. Mancias and Limón are hit in the head and go down. Hernandez tries to shield himself but a policeman standing in the back row winds up, surges forward, and strikes him in full stride across the top of his head. As he goes down, six other officers club him.

"When I got up, about eight officers were holding him down, beating him on the ground," Mancias told reporters that day. "They were continuing to beat him; he was handcuffed on the ground and they were continuing to beat him. They were Austin police officers. They did not have their nametags on, not one of them."

The policemen gave Hernandez a severe concussion. They broke his wrist and several of his ribs, and opened a gash on his head that required eight stitches. Margaret Moore, who was then the Travis County attorney, prosecuted Hernandez for resisting arrest. After his conviction by an all-white jury, she pronounced herself very satisfied, saying, "People must be held accountable for what they do."

Building a Machine

The Brown Berets never had more than 20 members at any given time. As the Eighties progressed, the group fractured, and members spread out to work on their own interests. Rivera organized against Ronald Reagan's wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua with CAMILA, Chicanos Against Military Intervention in Latin America. Almanza traveled the state helping activists from other Brown Beret chapters and later assembled the environmental justice group People Organized in Defense of the Earth and Her Resources (PODER). Hernandez began building a political machine on the Eastside, organizing neighborhood associations, getting out the vote.

While neighborhood associations were common and already politically powerful in other parts of town, East Austinites had historically stayed out of those local debates. Hernandez understood the power that lay untapped; with organized neighborhood groups, the Eastside could get sidewalks and streetlights, stop homes from being bulldozed, and shut down the Holly Power Plant that polluted the barrio.

Hernandez and his best friend Marcos de Leon set up meetings with respected citizens across the Eastside. The associations they created – East Town Lake, Barrio Unido, Pedernales, Govalle, and Buena Vista – were grouped under an umbrella organization called El Concilio.

One goal of El Concilio was to win elections. The Brown Berets had helped leaders like Richard Moya, Gonzalo Barrientos, and John Treviño, who weren't from the Eastside, become the first Latinos to win elections in Central Texas. But over time, they came to believe that these pioneers weren't pushing hard enough for change. They began sponsoring their own candidates for local offices.

Hernandez also used El Concilio to improve Eastside housing. He placed members of the group into an organization called the East Austin Chicano Economic Development Corporation, which successfully pressured lenders to end the historic redlining of the barrio and built some of the first income-restricted housing on the Eastside in decades – a string of homes along Oak Springs Drive, a five-minute walk from Gilbert Rivera's boyhood home.

Zeke Romo occasionally drives past the homes and is pleased to see them still standing. He remembers Hernandez as much more than a young radical. "Sometimes people think of him as just being part of the boat races and Brown Berets," Romo said. "But he was also into economic development and empowerment of the community. That was a big dream of his, affordable housing and empowerment, building wealth."

El Concilio finally began to succeed in electoral politics in 1990, when de Leon won the race for Travis County commissioner, the seat formerly held by Richard Moya. Hernandez was bending the world to his will. "He was creating alliances, he was building empires," Delgado said. "He was growing so fast, and he was doing what he had set out to do for our barrio."

Paul's Stroke

In August of 1993 Hernandez and his girlfriend, Leslie, took a vacation to the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. Hernandez never spoke publicly about what happened there, but before he died he wrote the story down and shared it with Bertha Delgado.

"At 10:04am, on August 20th, I was finishing my hundred crunches," he wrote. "The day before I had spent exploring the ancient Mayan ruins in Uxmal, Mexico, enjoying the powerful feelings left by the ancient heritage. At 10:06am I began my pushups, when something that felt like an electrical charge came down my left side. I could not move any part of my left side."

A blood vessel in Hernandez's head had ruptured. He'd suffered a stroke. He endured a week of agony as Leslie worked frantically to get him back to the states. When doctors in Austin saw him, they predicted he'd never regain the use of his left side. He was only 47 years old.

"I was numb, but I didn't believe it," Hernandez wrote. "I had dedicated my life to the human rights movement and had more to give. I wanted to get married to the woman I loved. It wasn't easy. I spent nine months in a wheelchair before I could take my first steps. I was like a baby and I had to learn to walk again. I proposed to Leslie but the wedding date would be set when I could walk down the aisle. And it took two years."

After the marriage, the couple lived in the Bouldin neighborhood of South Austin. Hernandez stayed involved in Eastside politics, consulting with colleagues on the phone, but spending more time with friends and family. His energy level fluctuated.

"It changed his organizing capacity," Almanza said. "He couldn't move around as well and that was real, because when you can't move around, even though you can be on the phone talking, it's not the same. Just being able to move around and talk to people. We didn't have as much communication, that's for sure." Like many, Almanza was convinced that Hernandez's health problems were the result of the blows to his head from police batons.

A year after the stroke, de Leon lost reelection; over the next decade, he and other El Concilio candidates lost races for City Council (then still elected at-large, with a seat reserved by custom for a Latino member under the so-called "gentlemen's agreement") and the Texas Legislature. Hernandez still spoke before the council, still talked strategy with El Concilio members, and still had passion for the issues. Then, in 2007, he underwent back surgery, hoping to improve his mobility. The operation was unsuccessful. Hernandez was confined to a wheelchair, his energy further reduced. He moved back to the barrio.

Delgado was pleased to have her godfather near; she was beginning her own activism and needed his guidance. She also wanted to care for him. "He was fragile. We didn't take him out too much. If we took him anywhere it was to Metz Rec [Center]. And when it was time to go he'd be like, 'That's it? The party's over?' And I'd be, 'Yeah, the meeting's over and Leslie's waiting for you! You need to go home, you are not gonna go have a beer.'

"And we'd carry him to the car and put him in his wheelchair. And I was like, I know one day he's not going to be here so this is our job, this is our obligation. He would be like, 'Sorry mija, I'm heavy.'

"'It's okay, it's okay, I got you.'"

Accepting the Gifts

Paul Hernandez's memorial was held at Chicano Park. Bertha Delgado spoke about the event: "Raúl Valdez came out with an acoustic guitar, played music. He talked a little bit about Paul. And Susana Almanza came, PODER did an Indigenous blessing. Leslie Hernandez, his wife, came and spoke. It was just beautiful. We had over 200 people here. And we registered voters, we fed the families, we had beautiful shrines and photos ... everything was perfect. Just the way he would have wanted it."

In the weeks since the memorial, Delgado has spent a lot of time at the park. She and her team, Arte Texas, have just finished the restoration of the Chicano Park Mural on the cinder block walls of Martin Pool. Ramon Maldonado painted the original mural in 1982 as a teenager, without a permit, and now he and his team have brightened and enlarged it. This time, instead of being threatened with jail, Maldonado is being paid by the city for his work.

The mural has many new elements, but none more vital than the portrait of Hernandez in his brown beret. Maldonado and Mando "Taner" Martinez came out the day they heard of Hernandez's death, chose an empty space on the wall, and began painting. "It was the perfect spot for Paul," Delgado said. "It's right here on the land, the sacred land that he fought for."

Chicano Park is one of the few places on the Eastside that hasn't been touched by the gentrification of the last two decades. In the neighborhood around the park, dozens of old bungalows have been replaced by large, cold townhouses. Susana Almanza and her environmental justice group, PODER, have defeated multinational oil companies and other giant industries over the years. Still, she sees gentrification as the biggest challenge the Eastside has ever faced.

"That's the number one thing, is just trying to stay," Almanza said. "Trying to sustain ourselves and our neighborhood. Trying to stop the displacement."

To Almanza, Gilbert and Jane Rivera, and the remaining Brown Berets, what is happening on the Eastside is a slow-motion tragedy. "The fabric of this neighborhood is like a quilt," Gilbert said. "And every piece of that quilt is a neighbor you know, a relative, a friend, a school, or whatever. And for the last 20, 25 years or more, that quilt has been torn apart thread by thread and thrown away. So what we have now is the remnants of once-great neighborhoods."

Almanza believes that the displacement could be stopped. In 2018, PODER proposed a six-point plan to address it. Among the measures were guaranteeing a right to stay for residents and a right to return for those who have left; establishing a low-income housing trust fund; and using publicly owned land as sites for affordable housing.

Almanza's plan has gone nowhere. "It's because of who's running the show," she said. "The Real Estate Council [of Austin], the Chamber of Commerce, the wealthy people, that 1% or less than 1% that are running the show. They want Austin to look a certain way, and money is all that counts, humanity doesn't. It comes second."

Gilbert and Jane Rivera agree. "Paul always said – and always stood by it until the day he passed away – that the experience that we're having today and that we've been having since the Seventies is premeditated," Gilbert said.

Jane elaborated: "And that is what Delgado grew up with. All these things that we were fighting against as adults, she grew up seeing and having to survive as a child. And now she's the one who is fighting to save what's left of our neighborhood. And I believe it's much harder for her generation than ours, because so many have been removed."

These lifelong activists cherish Delgado; they believe she will carry the struggle forward when they are no longer able to. But as a girl, Delgado didn't want to be that person. She didn't even want to stay on the Eastside – she dreamed of working in Manhattan. Then, as she moved into her 30s, she realized she had a different destiny.

"It was like, in my blood. And I didn't understand it," she said. "But Paul made me understand it. And he told me that you have to accept the gifts.

"And you want to do everything he had set out to do. You want to accomplish it for him. For the people, yes, for sure, because we were always there to serve and protect the people. But he had strategies, he had ideas, he had operations, and he wanted to implement those things, because he started them. And it took me a long time to understand that – I had to learn the life of Paul."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.