How to Jail the Poor

Travis County tries to fix its Driving While License Invalid issue

By Chase Hoffberger, Fri., Sept. 21, 2018

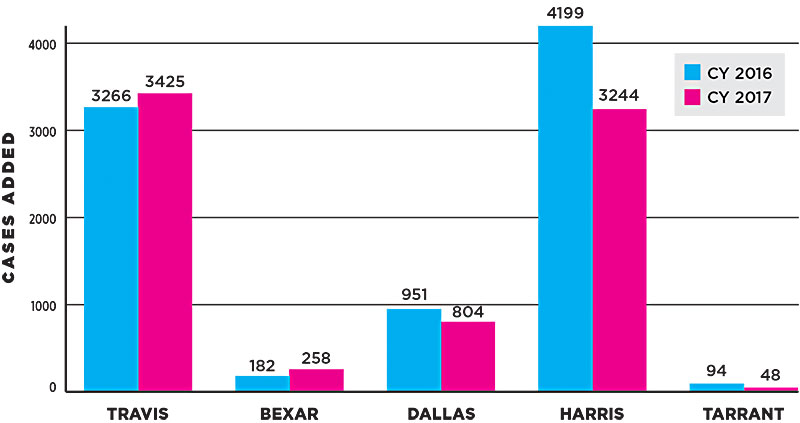

Two years ago in Travis County, 3,266 people got booked into the county's criminal justice system for the high crime of driving somewhere without a valid license. That figure has not been an anomaly; in 2017 it was actually worse, at 3,425. Census data tracks Travis County's population at 1.23 million people, meaning that if everybody who got booked on the charge was a resident here, they'd be one of every 376 people.

How bad is that rate? Look to our neighbors in urban counties. In 2016 in Bexar County, population 1.95 million, only 182 cases were added, or one for every 10,714 people. And in Dallas County, population 2.61 million, courts got only 951, one of 2,744.

In fact, in 2016 the only Texas county with more of these cases was Harris, which took on 4,199. But Harris County is huge; its population now over 4.6 million, meaning we're still looking at one in 1,095 residents. And in 2017 Harris County actually lowered that figure to 3,244, booking 200 fewer people than were booked in Travis County. Local prosecutors were still seeing more cases here than in Harris despite Travis having 3.4 million fewer people.

And if all this doesn't reflect poorly enough on Travis County, just look to Tarrant, population 2.05 million, where in 2016 the court system added only 94 new cases – one in 21,808 – and the following year saw that number cut to 48.

Discretionary Measures

These numbers moved through the local circuit in April, shortly after attorney Betty Blackwell – who's president of the Capital Area Private Defender Service, which provides representation to defendants who can't afford to retain an attorney – asked why her organization must reallocate $500,000 of its $3 million budget to defendants in these cases. "We're trying to get more money for murder cases, serious sex cases – second attorneys, investigators, and social workers," she elaborated to me in June. "And we're going to spend our limited resources on this?"

Blackwell's proposal for law enforcement: Don't file these cases in the county courts. File them all as class C misdemeanors, and put offenders through municipal court, where they'll get fined but won't face the threat of jailing (class B misdemeanors require bookings and an appearance before a magistrate judge, and carry a maximum sentence of 180 days in jail), and can work with students at the UT Law School's Driver's License Reclamation Project to pay their debt and renew their license. "We aren't supposed to have debtors' prisons," said Blackwell. "We aren't supposed to imprison people just for money." Yet every year, more than 3,000 people in Travis County face the prospect of just that.

A person can lose their license for a set amount of time for a lot of reasons, but the more open-ended suspensions are often the result of financial failures: drivers either did not pay their traffic tickets or neglected to pay auto insurance. The Texas Tribune covered this in detail in August. Since 2003, the state's Driver Responsibility Program has sucked up surcharges from traffic tickets and reallocated that money to emergency rooms around the state. Once a driver is entered into the program, they have 30 days to pay their fees or get onto a payment plan. Should they not do that, DPS suspends their license. (A bipartisan spray of state legislators agrees that having poor people fund trauma centers through traffic tickets put on poor people is not the best way to run government, but there's never been support to change the law; nobody's identified another cash cow for the health centers.) Drivers who avoid the DRP can also lose their license if they fail to show up for court hearings.

Those fees get levied upon offending drivers no matter what type of misdemeanor they're charged with, but the option for law enforcement officials to use discretion when filing charges – to choose between a class B or class C – has been afforded to them since 2007, when two laws changed the way the low-level offense would be prosecuted around the state. House Bill 2391 established cite-and-release, meaning that officials could issue a class B citation to a driver but not book them into jail; instead, they'd receive a summons date before a magistrate judge. Meanwhile, HB 1623 stipulated that first-time offenders should be cited with a class C and repeat offenders should receive a class B. But there's wiggle room within the statute, and Tarrant County in particular has used that space to drastically lower its number of dispositions.

"'We trust y'all,'" Tarrant County prosecutor Dawn Boswell said her office told local law enforcement agencies at the time. "'You're the ones who have to prioritize what resources are available to you and what offenses are priorities. ... We prosecute the crimes that you give us.' That's something that's just sort of evolved. Since 2007, the numbers have dropped every year."

A Tough Process

Travis County houses a wide variety of law enforcement agencies, but the Austin Police Department is its largest, and accounts for the vast majority of DWLI offenses. The department's discretion to file an incident as a class C or something more severe is in accordance with state law, said a department spokesperson, wherein cases are filed as class Bs if they're a repeat offender, have a DWLI conviction, or have been driving without insurance. Last year, by mid-September, APD had administered 888 DWLI arrests and exercised cite-and-release in 772 cases. Those numbers are both down this year: arrests are at 840, cite-and-releases are at 699.

But of all the cases that come through the county courts, DWLIs "probably take the most time," said County Court-at-Law Presiding Judge Elisabeth Earle of the class B filings. "There are so many of them." The same holds for attorneys and defendants. "If you're charged with a criminal offense, you have a pre-trial, a hearing, and a jury trial," said Earle. "You know what kind of setting you have." For DWLI offenses, which are administrative by nature, "you aren't going to have a pre-trial or a hearing. The case is going to get dismissed. It's just getting defendants to court." The county dismisses around 65% of its DWLI cases – higher than Bexar, Dallas, and Harris, all of whose figures hover between 38% and 55%. Tarrant, no surprise, runs its dismissal rates below one-quarter.

Cases get dismissed if the offender can get their debt paid and license renewed, thereby making it legal for them to drive. (It's not a crime to have a suspended license, only to drive with one, though everybody I spoke with noted that a suspended license is rarely enough to deter someone who needs to drive somewhere from getting behind the wheel. Unfortunately, not everybody is attentive enough to secure an occupational license, which would allow them to drive in necessary instances, when their regular license is rendered invalid.) Settling their debt is something that ultimately only the offender can take care of. The only way they can do so is by going to the Department of Public Safety.

DPS is not exactly known for being user-friendly. The agency got audited this summer by the state's Sunset Advisory Commission, whose first order of business was how DPS "has not maximized its resources to adequately improve driver license customer service" – another story for another time. When they do suspend your license, a letter of notification is sent to the address for you that they have on file. DPS does not dabble in email, so if you've moved and not re-registered your address – or if you're too poor to afford a home – you won't receive that notification, and won't know for certain that your license has been suspended until you get pulled over for speeding or something like it.

Should a driver be fortunate enough to receive DPS's letter of notice, the primary method of paying their debt is through the agency's online portal. (Those without internet can pay by mail.) DPS used to have compliance offices where people could go for help, but they've since been shuttered, and telephone wait times for a service representative can often extend beyond one hour. DPS's License Eligibility website offers no type of assistance program – no help beyond an elementary FAQ – and one must pay off these fees somewhat quickly; extended delays bring new DRP surcharges that'll make it even harder to renew.

Blackwell routinely works these types of cases, and says "every lawyer in my field has a horror story about some client going to jail based on bad DPS information." Often, it's that the information DPS is working with is out of date: DPS takes 30 days to process someone's payment, meaning it takes 30 days after someone has sent in money for their license to get renewed. Which means there are instances in which drivers may have complied but still face arrest for outstanding payments.

And there are other fees that can be accrued without the driver knowing of them. Blackwell points to one, a $10 monthly monitoring charge for having an ignition interlock device on one's car; not to operate the interlock, just to have it in their car. A driver can have a valid license suspended for not paying that fee, even if they've never been told they owe it. "What all the other counties have obviously done is recognize that, 'Okay, they really don't know'" about the surcharges, said Blackwell. "They're really not doing this intentionally. Given the opportunity, they'd try to figure this out."

That's something that Vicki Ashley, the Travis County Attorney's Office criminal trial division director, can agree with. "I hear it called a poverty crime all the time, and I believe that," she said. "I know there are some people who lose track of things. Once they're stopped by an officer, they can figure it out and pay whatever small amount they owe. Typically, we don't see those people again. The people that we're seeing over and over again in large measure have gotten themselves into such a deep financial burden that they don't see a way out. They cycle through with DWLI arrests or citations or charges, a couple times a year. Every single time it adds surcharges."

Drivers would still face these fees when they're cited for a class C misdemeanor, but in cases like those, may do so without the threat of being jailed, aligning with the city's recent efforts to decriminalize the act of being poor.

Searchin' for Diversion

Ashley need only look at the ever-growing list of repeat DWLI offenders whose cases come through her office to notice that having an invalid license rarely stops someone from driving. And in that respect she appreciates that locally the outcome of these cases is more often than not a dismissal. "For 10 years or more," she said, "we haven't attempted to convict anybody of this offense. If they were charged, once they're filed here in court, our offer to defense attorneys, appointed attorneys, or pro se defendants – which a lot of them were – the judges have been working through the years to say, 'We just want you to get legal on the street.'"

Ashley, her prosecutors, and misdemeanor judges like Earle can't encourage a defendant to seek a dismissal – part of the reason why 36% of these cases still see guilty pleas, which remain on defendants' criminal records – but in cases where defendants do seek such an outcome, there are a number of tools they can use to get out of the mounting debt. Most known is the county's law library, on the first floor of the county's Granger Building (314 W. 11th), where attorneys work part time to provide the tools and educational resources necessary to get their license in good standing. "They've got access to some DPS records that I don't have access to," said Ashley, "where they can help figure out if somebody's got a ticket in East Texas or West Texas or Corpus [Christi], or wherever. ... Class Cs aren't reported on a typical DPS/FBI background check. All of those speeding tickets and running red lights that are happening in other counties, we don't see that."

But Ashley had been looking for some type of relief for these types of offenses, and last fall began exploring methods for utilizing the state's cite-and-release law to establish a diversion program for DWLI offenses. The county has seen success with diversion programs for both shoplifting and possession of marijuana offenses, both implemented by Nick Chu, the justice of the peace in Precinct 5, and wanted to expand the model to include another of the most occurring cite-and-release offenses. "We were talking about DWLIs and saying, 'That's our next one, but it's going to be complex,'" recalled Ashley. "It's not like shoplifting or POMs, where you kind of know what the facts are. These take sifting through all the reasons why [an offender's] license could be suspended, and figuring out which individual one is the case."

Ashley said she and her colleagues were in the middle of that process when they were sent the county-by-county data. She admits to being surprised at how Travis stacked up to other counties. "We just assumed they were dealing with the same thing we were dealing with," she said, "which is this mounting thousands of DWLIs."

A New Path

The way cite-and-release cases used to work was that offenders would be pulled over, cited, and told to appear on a specified date before Judge Chu, who would send them to pre-trial services to get a personal bond approved, something that Ashley said would happen so long as the individual would show up to JP5 on time. Individuals would then take their bond to the bonding desk at the Travis County Sheriff's Office, where they'd get fingerprinted and photographed, then sent back to Chu, who'd magistrate their case and set them to appear before a judge in a county court-at-law.

But that procedure changed on June 15, when Chu and Ashley's office coordinated to implement the DWLI Diversion Program, a system for recalibrating the charges against individuals cited for DWLIs to best utilize the time available to prosecutors and judges, and also lessen the legal liability of individuals who've found themselves facing the prospect of jailing over unpaid fines.

Now, when a defendant appears before Chu for a DWLI class B, their case will be reset for 60 days from that date, giving Ashley's office time to sort through the circumstances and make a determination as to whether to pursue the case as a class B or reject that and refile the case as a class C, to be handled like any traffic ticket, except through Chu's Downtown court.

Considerations include whether a collision brought on the citation, whether the incident left a victim, and whether the cited individual is a repeat DWLI offender. Chu said September 14 that 528 cases have come through his court as part of the diversion program over the past three months, with 278 getting rejected as class Bs and refiled as class Cs. (177 of those have already been processed through JP5.) He called the program a natural progression for his court, another way to de-emphasize nonviolent misdemeanors that can otherwise be handled at a lower level than the county courts.

"These are people who have either fallen behind on an archaic system built to tax people in order for money to go somewhere in the state that ... the Legislature should find another way to fund [emergency rooms] besides taxing a bunch of poor people," he said. "Or they're people who just don't know that their license has been suspended. Or they didn't know that pleading guilty to multiple speeding tickets has collateral consequences.

"My thought was, these are people who are victims of circumstance. What can we do, within the parameters of judicial ethics and the parameters of my court, to help?"

Number Crunching

DWLI Cases Added by County

In both 2016 and 2017, Travis County courts added more DWLI class B misdemeanor cases per capita than Bexar, Dallas, Harris, or Tarrant counties.

2017 DWLI Dispositions by County

Travis County DWLI class B misdemeanor cases get dismissed at a higher rate than those in any other county.

| Cases Disposed | Travis | Bexar | Dallas | Harris | Tarrant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dismissals | 1,845 (64%) | 128 (54%) | 350 (38%) | 1,711 (54%) | 9 (19%) |

| Deferred Adjudication | 40 (1%) | 52 (22%) | 157 (17%) | 112 (4%) | 9 (19%) |

| Convictions – Guilty Plea | 987 (34%) | 53 (22%) | 406 (44%) | 1,344 (42%) | 30 (63%) |

| Convictions – by Jury or Court | 2 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

– Source: Travis County

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.