What Follows Five Years of Failure at Mendez Middle School?

Making the grade

By Austin Sanders, Fri., Aug. 31, 2018

Two weeks ago, when the Texas Education Agency released district and campus scores as part of its new A-F accountability system, five schools in the Austin Independent School District received failing grades. That designation for one such school, Rosedale, at 49th Street and Burnet Road, was particularly galling for district officials, who argued it should never have been rated: The school services students with severe special needs, and many are unable to even give answers on the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR) exams that are a major component in establishing campus grades. Officials described the school's 56% score as "simply demoralizing" to faculty and parents, and considered it clear evidence of one way in which the A-F system needed to change. In the future, they hoped the district could petition the state to exempt schools such as Rosedale.

More expected was the mark for Mendez Middle School, which received its fifth consecutive failing grade. Usually that brings sanction by the state – which used to close those schools down, or take control of them from the district – but a new law passed by the Texas Legislature last year now allows districts to partner with charter schools to improve a campus' performance. So in July, the TEA approved a contract between AISD and the Texas Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Coalition (T-STEM), and gave the group control over the school's budget, curriculum, and personnel decisions. Communities in Schools of Central Texas and the UTeach Institute also provide campus support.

The law stipulates Mendez be exempt from receiving a grade at the end of the current school year, but the Dove Springs school will be graded again in 2020. If it gets another failing grade, AISD could again be faced with the decision to close down a community school. Critics of the A-F system say this is just one of the problems with how TEA assesses school performance. They say the grades are punitive and ignore the holistic learning experience that many AISD schools offer. They'd like an accountability system that relies not purely on academic performance, but also incorporates the "culture and climate" of a classroom, intrinsically valuable programs such as fine arts or athletics, and other measures they say are important to judging a school's level of success. But for the next five years at least, according to TEA Commissioner Mike Morath, A-F will be the measure by which Texas public schools are judged. Understanding how the system works, what it overlooks, and how the district plans to respond will play an important role in how AISD's schools are viewed in that time.

The Meaning of Failure

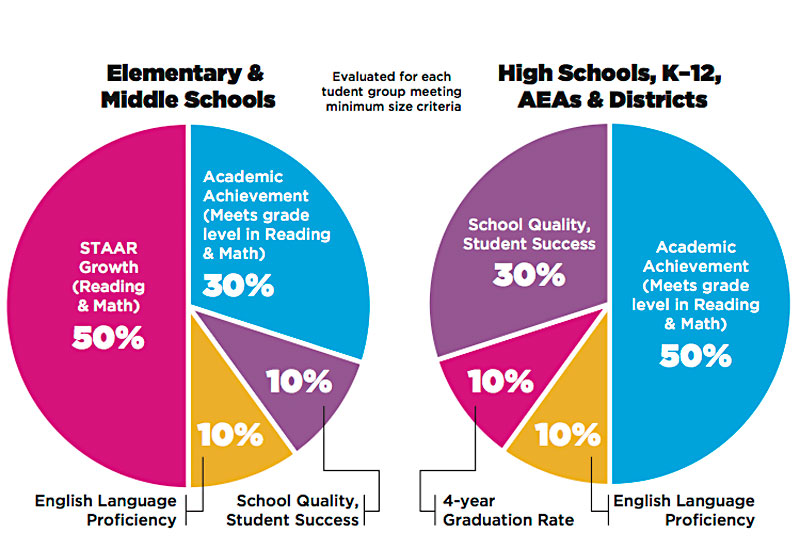

Since 1994, the state has issued some sort of accountability rating to public school and open-enrollment charter districts. The methods of determining a school's performance have changed, but the frustration school leaders feel about how their performance is measured has remained constant. The latest iteration of a state accountability system, signed into law in 2015, directs the TEA to create a rating system which assigns an A-F letter grade to schools and districts. In 2017, Rep. Dan Huberty, R-Houston, who chairs the Public Education Committee, introduced House Bill 22, which would incorporate some of the feedback gathered by the state's education agency. The changes brought by HB 22 included establishing three performance "domains"; reducing reliance on standardized tests; postponing campus grades to August of 2019; and introducing a "local accountability system" pilot program in which districts would be allowed to develop a state-approved grading system to factor into the overall score for individual campuses.

Lawmakers supporting the A-F system argued that the grade scale – replacing the previous accountability measure of either "Met Standard" or "Improvement Required" – would bring more nuance to school ratings, and would be easier for parents and administrators to understand, because letter grades represent a familiar grading scale. In reality, the A-F system uses complex formulas to produce four letter grades for districts and individual campuses: one in each of the three domains (Student Achievement, School Progress, and Closing the Gaps), and one that's a sum of all three.

• Student Achievement looks at three factors: performance in the STAAR exams (40% of the total); College, Career, and Military Readiness (CCMR, 40%); and graduation rates (20%). The CCMR metric is seen as a step forward for school accountability, because it attempts to look beyond test scores by factoring in industry certifications, college credit earned while in high school, and commitments to enlist in the U.S. armed forces. Critics note that some of the qualifying CCMR criteria are still dependent on test scores like AP exams and SAT and ACT scores. And in grading elementary and middle schools, STAAR accounts for 100% of the grade.

• School Progress is broken down into two sections: Part A looks at how students improved year-to-year on STAAR exams; Part B looks at how students improved on STAAR exams and CCMR (where applicable) relative to other campuses or districts with similar percentages of economically disadvantaged students. Critics of A-F give the TEA credit for Part B, because it factors in the economic status of students, but they still point to the overreliance on test scores as a recurring problem throughout the system's formulas.

• Closing the Gaps parses students into 14 distinct groups, seven of which are based on ethnicity. (The others include economically disadvantaged status, current and former Special Education students, English Learners, and whether or not a student has been continuously enrolled in school.) Individual campuses are assessed based on how effectively they are helping to "close the gaps" in specific areas – a slew of individual components that differ depending on if the campus is an elementary, middle, or high school – for each of the 14 groups. Campuses are given points for each group that hits the state's target in each component, and that number is used to calculate the total Domain Three score. For instance, in 2017, Mendez failed to hit state targets for Hispanic students in reading and math, so did not receive points in those categories. But it did hit state targets in reading and math for Special Education students, and got points in those components.

Confused yet? We're almost done. Once scores are calculated in each of the three domains, the higher of the Domain One or Domain Two scores is weighted at 70% and combined with the Domain Three score, weighted at 30%, to produce the final score for the district or campus. Excelling in certain areas qualifies districts and campuses for distinction honors. Conversely, failing to hit targets in certain areas will require additional targeting and support from the state.

Although Mendez's first A-F grade technically doesn't count against the campus, because it's exempt as a result of the district agreeing to bring in a charter, it did receive a 54%. After five years of missing the target, the Mendez community is ready for change.

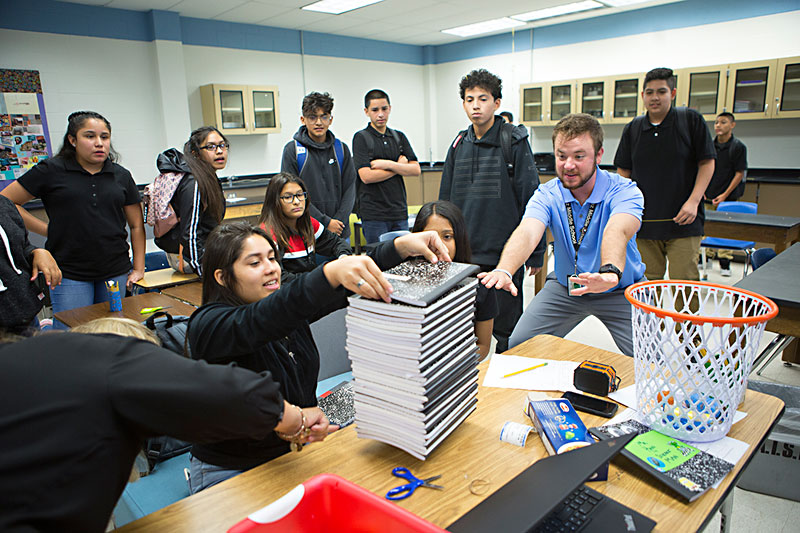

A Day at Mendez Middle

The scene inside Blair Hanner's eighth-grade science class looks out of control. Students gather in groups of four around tables and couches, talking excitedly about a project. They're constructing towers using toilet paper tubes, tape, and other supplies, with the goal of stacking as many composition books on top of the structure as possible. Other groups are trying to construct the tallest tower in the room, climbing atop tables to steady their towers. Hanner bounces back and forth between groups, answering questions, giving advice, offering praise, and keeping the kids from crashing.

It looks like a frenzy, but it's precisely what Hanner wants. "Controlled chaos is exactly what I'd expect anyone to see when they walk past my classroom," he said. "A lot of the old teaching strategies we used were drill-and-kill, and I am completely straying away from that with this new [problem-based learning] model."

Spend any amount of time around public education activists and you'll hear those terms: "drill-and-kill" and "problem-based learning" (which is sometimes "project-based learning," or often just "PBL"). The former is excoriated as an instructional method that "drills" students on content found in state standardized tests, often through repetitive worksheets and an avalanche of assessments, that results in "killing" a student's desire to learn. "PBL," meanwhile, represents an antidote, creating a space for students to master content standards while exercising their imaginations and critical thinking skills through collaborating with one another on complex problems, such as Hanner's tower project. One student walked me through her group's process. "We thought two rolls would be stronger than one," she explained. "So, we cut it into two pieces and taped them together." Their tower held 41 books, more than any other in the class.

After Mendez's fourth failing score in 2017, AISD officials found themselves at a crossroads over what to do with the school. Facing state control or closure of the campus, AISD leaders chose instead to use a new law passed by the Texas Legislature. For the next five years, the school will be operated by T-STEM, with AISD offering resource support. (Per the contract between the two, the agreement can be terminated early for a number of reasons, including "the failure of T-STEM Coalition to satisfy program services and performance goal obligations ....") In exchange, the school will be sent additional per-student funding from the state, and TEA will exempt it from being graded at the end of the year. Among the many changes T-STEM will bring to Mendez, one of the most prominent will be an emphasis on PBL. Students in all classes, across all grade levels, will spend more time engaged in hands-on, problem-solving activities designed to teach content standards found in the STAAR exams, while stimulating creativity and collaboration within and among students. The idea is that students will be so engaged by the work they are doing that they'll want to spend more time in the classroom. School leaders hope more time in the seat will translate to improved academic performance.

One of those school leaders, Principal Joanna Carrillo-Rowley, will play a pivotal role in Mendez's second-chance year. Carrillo-Rowley is something of a ringer, recruited by T-STEM from Midland ISD, where she established a reputation for turning around schools. With over two decades of experience in public education – including nearly half of that time leading schools as a principal or assistant principal – Carrillo-Rowley is well-positioned to bring the changes parents and teachers have longed for at Mendez.

Before she agreed to accept the position, however, Carrillo-Rowley toured the campus in May to see firsthand what she'd be getting into. She described a sense of defeat that hung over the faculty and students, but also "a hunger to succeed" that inspired her to commit. "I've been in schools before with teachers that want to succeed, and just need someone to lead them," she said. "I saw that at Mendez, but I always remind them, it's not just me that will get us there. We're a family."

Hanner and other teachers I spoke with agreed that Carrillo-Rowley helped reinvigorate the staff, 60% of whom decided to stay on in May after they were presented with T-STEM's plan for the school. (Carrillo-Rowley hired 22 new teachers with varying levels of experience to fill the vacancies.) Teachers described a "cultural shift" that emphasized establishing relationships with students. Each teacher will have a 30-minute "family time" period each day in which students can open up to their teacher and classmates about challenges they're facing outside of the classroom, something that Carrillo-Rowley said is important to establishing trust between student and teacher.

Kaeli Helmink, a teacher who works with small groups of students to improve their reading comprehension, also said Carrillo-Rowley and the T-STEM leaders set a precedent early on that the teachers would be trusted to create lessons and conduct their class in the way they thought would work best. "We still teach" state content standards, Helmink explained. "But we get to tap into our creativity by designing our projects around them how we want. ... It has been hugely empowering."

But Carrillo-Rowley has no illusions about the challenges she, her teachers, and the student body face. Over 90% of the student population is classified as economically disadvantaged, and nearly half are English language learners; both groups are disadvantaged when it comes to taking state tests. "Am I nervous about scores? Yes, absolutely," Carrillo-Rowley said. "But as I've learned, you have to put systems in place for a kid to become successful. ... That's what we're all about right now, establishing relationships and keeping kids in their seats, so they can learn."

The Authentic Experience

Needless to say, public school officials who decry the premium state leaders place on standardized test scores are frustrated with the A-F system. Each of the three domains depends, to some degree, on how students perform on STAAR exams. That's a problem, says Ed Fuller, an education researcher at Penn State University (and before that, at UT) who studies school accountability systems in several states. He says there's a "strong correlation" between a student's "background characteristics" and their scores on standardized tests, and that's a flaw in any accountability system that relies too heavily on those scores.

Students who are economically disadvantaged, English language learners, or who have special needs don't perform as well as their peers on standardized tests. "These are factors that are generally outside the control of the teacher in the classroom," Fuller said. "It's unfair to expect those students to consistently match the performance of their peers." He added that school funding, access to quality teachers, and the economic conditions in the area are all factors that contribute to test scores that schools and districts have little to no influence over.

Fuller did acknowledge that Texas' A-F system attempts to address that problem by comparing a school or district's performance relative to similar schools and districts, and by separating out different groups of students and comparing their performances. But he said the system overall "was not fair and accurate," because of its reliance on tests scores. "The system Texas has set up is going to send some incorrect messages, because they are not doing enough to remove the influence of factors that are outside the control of the school in calculating grades."

A chief complaint among A-F critics is that beyond the easily comprehensible letter grades that serve as the face of the system, the underlying components that produce the letter grades will be overlooked by the casual observer. Although the TEA produced a detailed data portal that contains the raw numbers that make up the summative scores, it remains to be seen how that tool is being used. TEA spokesperson Lauren Callahan said the www.txschools.org website had received 1.57 million unique visitors, one possible measure of how much the data is being viewed.

But many parents, teachers, or students will see the final score for their campus or district and stop there. "It's easy to draw conclusions," said Debra Ready, AISD's executive director of accountability and assessment. "But I don't think it's all that easy to understand." Ready said the accountability system doesn't do enough to factor in the challenges that districts and schools face in educating economically disadvantaged students and English language learners. She pointed to the difference in district scores for AISD (89%) and neighboring Round Rock ISD (90%). Though they're close, AISD serves a student population that is 53% economically disadvantaged and 28% English language learners, compared to RRISD's 26% and 9%, respectively. Parents who don't dig into the data to get a fuller picture of how a score is calculated may miss out on that nuance.

Lisa Goodnow, AISD's associate superintendent of academics and social & emotional learning, stressed that parents valued other factors beyond STAAR results that make a school beneficial to students, but are not factored into the A-F grade. She pointed to the district's popular dual-language programs, fine arts academies, and early college high schools that "prepare students for success in career and life."

District officials often pointed to the "authentic experiences" they say are created in the various campuses that utilize project-based learning (the approach Mendez will take in the coming year) as an important factor in assessing school quality that the A-F system misses. They say a PBL curriculum teaches important life and career skills, such as cooperation and collaboration, problem solving, critical thinking, and communication, that are not easily measured in an assessment. "You're not going to get a job where your performance is based on whether or not you can answer a multiple-choice question," said Michelle Cavazos, AISD's chief officer for school leadership. "The more we can give our students authentic experiences, the better prepared they'll be when they leave us."

Effective Measurements

AISD is one of 20 districts participating in the pilot program that was added as a provision of HB 22 after pressure across the state. District officials sought input from teachers, students, parents, and other community stakeholders to help develop what they hope will be an effective balance to the state-mandated accountability metrics. Ready described a local accountability system that would take into account literacy rates in kindergarten through second-grade students, proficiency in project-based learning, teacher retention rates, how the district does with community engagement, and the impact of fine arts programs. And Goodnow emphasized that the system AISD developed will measure growth in more ways than the A-F system currently does, something she said was rated as a valuable metric for the AISD community.

The district worked with TEA researchers to develop a system capable of effectively measuring all of those data points in a statistically valid and reliable way. If the plan is approved – which could happen any day – the district will be able to fold the results of their own accountability ratings into the scores generated from the state's formulas, with each accounting for 50% of a school's overall score. "We've only implemented half of HB 22 at this point," said Ready. "And we're feeling confident that the community will be satisfied with the accountability standards we've developed."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.