To Build a Courthouse

Travis County moves to replace 84-year-old Heman Marion Sweatt with a massive new Civil & Family Courts Complex

By Michael King, Fri., Sept. 18, 2015

The need for a new Travis County courthouse had been evident for a long time. The existing courthouse was overcrowded, increasingly dilapidated, infested by vermin, and simply inadequate for its current purposes. Yet a new courthouse required support from both public officials and the public at large – the taxpayers who must foot the bill for all new infrastructure – and it had taken nearly a decade to get any progress on the issue. Each time the Commissioners Court attempted to move forward with the project, disagreements over the cost, the location, the scale, etc., delayed or derailed the process.

The daily newspaper summarized the opinion of the county judge: "All the departments of the building are badly overcrowded and a new courthouse has become a crying need of the county." The judge had been advocating for a new courthouse for years – despite the insistence of county commissioners to first try repairs that had quickly proven inadequate – and the frustration was building. "The new courthouse should have been built two years ago," said County Judge George S. Matthews.

The year was 1929, and then Travis County Judge Matthews was speaking of the $600,000 allocated for a new courthouse that commissioners finally appeared willing to spend (Austin Statesman, July 19, 1929). Matthews would eventually get his wish – the new Travis County courthouse would have its grand opening June 27, 1931, although by then the all-inclusive price tag had taken on a dramatic flourish. "Travis County's new million-dollar courthouse won the approval and commendation of several thousand taxpayers who attended the formal opening of the new seven-story structure at Guadalupe and 10th Street Saturday," reported the June 28 Austin American. (Matthews was in attendance, but he had since been succeeded by Judge Roy C. Archer.)

A Busy, Busy Place

Eighty-four years later, the arguments for a new Travis County Civil & Family Courts Complex – to be constructed, as it happens, on the land originally designated in the city's original "Waller Plan" as the site of a courthouse, and used for that purpose from 1855 to 1874 – sound historically familiar. Arguments for a new civil courthouse have proceeded for at least a decade, and the reasons echo across the century. The courthouse is overcrowded, dilapidated, infested with vermin, and simply inadequate for its current purposes and workload. (Jurors in the Twenties complained of bats and flying mites, both of which were occasionally bad enough to interrupt trials. Current courthouse administrators provide photos of "rat dander" in various corners of the building, of equipment covered against roof leaks, of metaphoric rats' nests of telephone and electric wiring crammed into storage closets and awkward corners, surrounded by tightly stacked boxes and files.)

The current Travis County Judge, Sarah Eckhardt, sounds quite a bit like her predecessor George Matthews. "We have a fabulous historic courthouse," she told a small group of reporters earlier this summer. "And its name [Heman Marion Sweatt, civil rights pioneer] reminds us how far we've come. But there's no doubt we need a new courthouse."

"As a former assistant county attorney," Eckhardt said, "I can tell you I have sat in the hallway of the courthouse between a woman seeking a protective order ... and the person who she was seeking protection from, having ridden in an elevator that's five feet by five feet with these two people, and the children involved as well."

That kind of story is recited often by courthouse regulars. At the same event, Judge Lora Livingston told of stepping around six children sitting in various stairwells – waiting for family members in court – on her way out of the courthouse that day. "There is simply no other place for them to wait," Livingston said. Judge Darlene Byrne, in her office outside her courtroom, described the crush of family law cases – about six an hour in her court – and her "holding cell" for county prisoners who needed to appear for one reason or another. "It's a couple of folding chairs in the hallway, right opposite my court reporter. She can't enter or leave her office without passing directly in front of those chairs."

Retired state District Judge John Dietz, who's worked on the project for a decade and steadily become the semi-official spokesman on conditions at Heman Sweatt, summed up the situation. "We're at our limits.... Programmatically, we are out of space. We have used every square inch of this building. We are using places that are not really designed to be courtrooms, or conference space, and we have no spaces to take care of families or children.... This is a busy, busy place."

Touring Heman Sweatt

In talking about the courthouse, Dietz – best known for his landmark 2014 ruling that the Texas school finance system is indeed unconstitutionally inadequate and inequitable – doesn't emphasize the high-profile civil cases that generate most of the headlines emanating from Heman Sweatt. Instead, he reiterates the sheer physical exhaustion of the building (with its 125,000 gross square feet on five floors now actually representing only about 75,000 square feet of usable floor space). A small indicator is that he meets three journalists, here for his semi-regular tour for those interested, at a small table outside the cafeteria. He recites the proximate numbers at his fingertips: In a building originally constructed for three courtrooms (and at the time, a jail), we now house "two county civil courts, two probate courts, JP [justice of the peace] court, 13 district courts, two district clerks with all their responsibilities...."

Dietz goes on to describe, more specifically, the heavy burdens placed on family litigants, in the various family court cases that represent about half of the 90,000-100,000 cases each year, including divorces, post-divorce modifications, unmarried people with children disputing custody arrangements – "SAPCR" cases, he says: "suits affecting the parent-child relationships, who gets custody, visitation, etc." Both the subjects and numbers are sobering. "I remember a judges' meeting in 1993," Dietz says, "when [now-retired] Judge Jeanne Meurer updated us on the CPS [Child Protective Services] docket. She said 75 children had been removed from their homes in Travis County. People were saying, 'Holy Cow!' Well, that number is now 1,300-plus [children in removal status]. That is a sad commentary on our family situations, but we are charged by law either to reunite them with a family, or if not, place them with foster parents or for adoption."

The result is a lot of families – confounded, damaged, broken – arriving at the courthouse to do various legal business, sitting or standing shoulder-to-shoulder wherever they can find a spot, too often tense with family conflict, with children in tow who are accommodated in whatever space attorneys or courtroom administrators can find for them. Hence the children scattered on the stairs, talking or reading or sitting quietly. Later, on another floor, Dietz will point to a folding table occasionally used by parents for diaper-changing – "come by later in the afternoon, and someone will be sitting there eating a sandwich."

Dietz is nevertheless proud of Travis County innovations that have kept the courthouse functioning even as the quarters became more cramped and obsolete. "We were the first in e-filing," he says of the now general requirement for civil cases of all documents being filed in digital form. "We're the most technologically advanced court system in the state; since 2004, the district courts have had an electronic docket system, including not just electronic files, but an electronic jury empaneling system." For prospective jurors who have gone through that process, it's not entirely electronic, of course – large numbers of online-qualified, prospective jurors can then find themselves standing in the Heman Sweatt hallways waiting for an available courtroom, eyeing the few over-filled benches with envy. Dietz told a county newsletter: "I want people to know that we have studied the functionality of the courthouse for 10 years, and that we have spent considerable effort finding courthouses across the nation that really work for their citizens. For example, we have requested space for a child drop-off center for citizens who need to bring their children to the courthouse and we are considering including a lounge or multifunction space that can be used for jurors so that they can stay in touch with their home, office, or just relax, instead of standing in the hallways as they do now. The new courthouse will be tremendously more functional than the 84-year-old building that we have now."

Dietz says that while he's "seen no piece of paper that can confirm it," he believes the courthouse is the third most-visited Downtown building, after the Capitol and Whole Foods. "I think that's right. In any case, we receive 200,000 people passing through this building a year, climbing the stairs or using one of the two elevators," which have become increasingly difficult to maintain. "We can't order parts for them anymore; they have to be specially fabricated."

Dietz says the new courthouse – drawing on best practices selected from courthouses in Brooklyn, Charlotte (N.C.), Jacksonville (Fla.), and elsewhere – is planned to accommodate contemporary demands of the judicial system, especially the need to serve as a one-stop shop for social services for families and children. "We spent two-and-a-half years developing a program, designing what is needed to answer the need." He recalls a Brooklyn courtroom effectively converted into a central office for social services, and says of the planned civil and family courthouse, "We designed it so it will be flexible to adjust from courtrooms to services as necessary, and to generally be more accommodating to the needs it will serve. We're having to be problem-solving courts, juvenile and family. We're the welfare office now, and we're the center for all those services that the children and families need." And he notes that the county has been overdue for adding another judge to handle the increasing load of family law cases, but says, "We simply don't have any space to put that person."

The Plan

On August 18, as the culmination of a lengthy planning process that included a few stumbles on the way (see "Courthouse Campaign Takes Shape," June 26), the Travis County Commissioners Court voted unanimously to place a $287 million bond proposal on the November 3 ballot to underwrite a new civil and family courthouse complex. It had been a very long time coming, but the unanimous vote – including Republican Precinct 3 Commissioner Gerald Daugherty, who might have been expected to balk at the price tag – suggested that virtually everybody is on board on the need to finally get this long-awaited project under way. Indeed, in terms akin to those of Eckhardt, Daugherty told a county CFCC project newsletter, "Since the Courthouse we are presently using is over 80 years old, it is imperative that we build a courthouse where people can administer adequate justice."

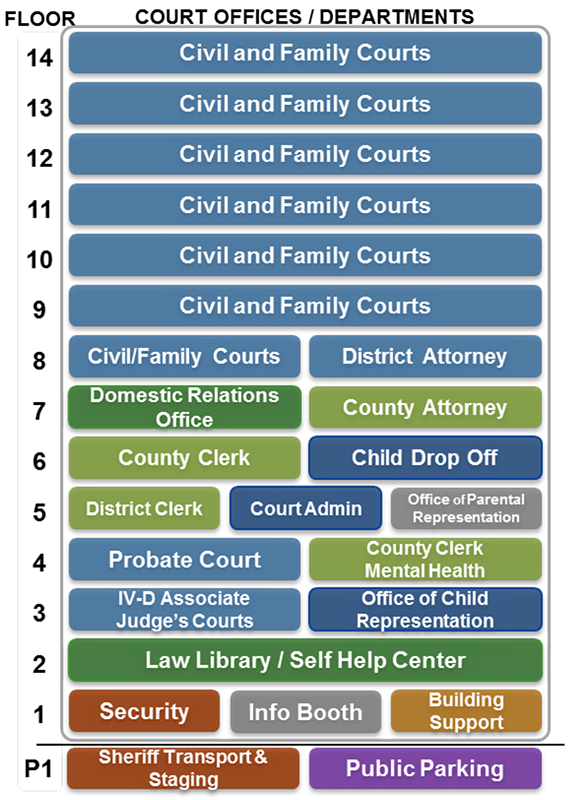

How does the proposed civil and family courthouse complex address the problems and needs identified by Dietz and the other officials? As currently conceived (with requests for qualifications just released for consideration and application by major contracting teams), the "design-and-build" specifications include 14 floors of courtrooms, offices, and flexible and retail space, and a below-ground parking lot with more than 500 spaces. As sketched on the conceptual schematic, the first eight floors range from an information area, upward through administrative and district clerks' offices, probate court, with county attorney and district attorney offices tentatively on the seventh and eighth floors.

The next six floors are dedicated to civil and family courts; where the current courthouse now has 19 courtrooms in a space originally designed for three, the initial buildout of the new courthouse calls for 28 courtrooms, with space for a total of 33 by 2035 (the rest of the building is also designed for interior expansion). The plan includes offices for as many as 35 judges, and the lower floors would include such innovative sections as a child care center (probably to be operated by a subcontractor) and on a lower floor, a law library/self-help center for pro se litigants.

Planners emphasize the security aspects of the building simply unavailable at Heman Sweatt. There will be separate, secure entrances for judges, families, and prisoners – segregating victims from accused abusers, for example, and inmate litigants. Since a courthouse is not a typical office building, and in the current historical context requires special features, both the structural foundations and many of the courtrooms will have extra security components – "Kevlar-reinforced judicial benches" is one of the items planners mention in discussing the architectural details.

However, since the building won't actually be designed unless and until Travis County voters approve the bond referendum, it's impossible to know precisely the potential appearance of the building – all the available renderings are essentially schematics. Eckhardt assures her audiences that the courthouse will be "architecturally distinguished" in the long tradition of Texas courthouses (and at least the exterior of Heman Sweatt itself, designated a historical site). Project manager Belinda Powell adds helpfully, "We know at least that [the] exterior [according to the design specifications] will be at least 50 percent glass."

Integral to the plan is a "second tower," to the south of the courthouse itself. While the foundations to that building are included in the current plan, the second tower is expected to be a privately built and leased space, and to become an income stream for the county, to be held in reserve until such time as county needs expand to assume the additional space. The second tower is also one of the financial "offsets" described by Eckhardt in presenting the plan. The judge says the plan includes additional income intended to lower the overall cost of the project over time; that income would include the ground lease for the office tower, the property tax generated by private use of that tower, night-and-weekend revenue from the underground parking, and the consolidation in the complex of county services that should allow the county to sell other parcels of land it will no longer need.

According to Eckhardt, the various offsets – although they cannot be included in the bond proposal itself – could eventually represent "as much as a 20 percent offset of the total cost, over time." That big ticket, winnowed slightly from an initial $294 million to the commissioner-certified $287 million, will likely be the biggest obstacle to persuading Travis County voters to support the project.

The Campaign

Virtually everyone who's ever set foot in the current courthouse in recent years acknowledges the building's shortcomings – even those initially skeptical of the county's plan – and grudgingly admit that something needs to be done. Powell, who as project manager has already participated in a few dozen public presentations, says the objections that arise tend to cluster around two seemingly related issues: cost and location. Some people simply balk at the price tag, and in the current political atmosphere, blanch at any increase in property taxes. To that objection, planners respond that the cost has been whittled to about $38 a year for the median-value-home county taxpayer ($360,000) – the homely campaign equivalent is "about a $3.50 taco a month."

A few others are convinced that the Downtown location is the problem – that if the whole project is moved out to some more remote tract of land, it would inevitably become cheaper. But even setting aside the logical presumption that a county courthouse – the seat of local judicial authority – historically belongs in the center of the county, Powell and her team point out that there would be no actual savings: Travis County already owns the current site, and construction costs for the type of building required remain the same whether completed there or on another tract. Moreover, argues Eckhardt, the available income from both the below-ground parking and the leased second tower would disappear.

The official campaign – "New Courts for Families" (www.newcourtsforfamilies.com), sponsored primarily by the Austin Bar Association (ABA) – has done preliminary polling that suggests there is at least potential public support for the bond. In May, Tulchin Research found that 54% of likely November voters endorsed a new courthouse in principle; when they were provided what the consultants called "balanced messaging" (pro and con) about the project, support grew to 61%. The consultants concluded that "the bond measure is well-positioned to win voter approval in November, assuming that supporters have the necessary resources to run an effective campaign."

In addition to the local bar (understandably hoping, at a minimum, for an improved workspace), the business community and construction industry will inevitably bring support, as will local labor groups. Robert "Bo" Delp of Workers Defense Project says the group anticipates supporting the project in principle, but wants first to make certain that "when the public money is used in construction, it really needs to benefit the whole community, including the workers who build the projects." He says WDP will be asking Commissioners Court for contractor assurances on living wages, safety training, workers compensation, and the like – all things that Eckhardt says the county is already pursuing.

Although organized opposition is yet to form, last week District 6 City Council Member Don Zimmerman released a formal proposal to consider relocating the project to far Northeast Austin, near Long Lake (the resolution is co-sponsored by D1 CM Ora Houston). "Putting the proposed courthouse Downtown doesn't make sense," declared Zimmerman. "Downtown is already very congested and expensive. East Austin would be much more affordable and would spur economic development in the 'Eastern Crescent' of the city." It wasn't the first time the planners had heard the theory, and they were quick to repeat the obvious objections: that moving the project wouldn't save money, that a remote location is worse for equitable justice (and the rest of the county), that dozens of bus routes (necessary for many families) serve Third and Guadalupe, while one serves the much less populated far Northeast, and so on.

Since Zimmerman's resolution can't even be considered in council committee until late September, it seems more likely a tactic to undermine the November bond vote than a serious alternative. Eckhardt declined to comment until such time as the resolution might reach the full Council. The ABA issued a response that concluded, "This resolution does nothing to help stimulate growth in East Austin. Instead, it subverts a well thought-out, financially sound plan the County has been working on for years."

During the course of his informal tours of Heman Sweatt, Dietz likes to recall that back in the Twenties, public officials and the public strained over the $700,000 original estimate to build the courthouse, delayed for several years, and were eventually proud to walk through and show visitors Travis County's "million-dollar courthouse." "Can you imagine," he asked reporters, "what 700,000 dollars works out to now, amortized over 84 years? I'd call it a pretty good deal."

That's one way to look at the numbers. Another might be considering the 1929 cost in 2015 terms, however approximate for very different circumstances. According to standard inflation calculators, $1 million in 1929 dollars represents roughly $14 million in buying power today. The Travis County population – 77,777 in 1930 – is now about 15 times that size: 1,158,281. Fifteen times $14 million works out to $210 million, and if we project to the 2035 population (1.6 million) that the new courthouse is planned for when fully built out, the total grows to $294 million – just about the scale of the current project.

Whatever Travis County voters decide, our successors in 84 years might well be looking backward, either in satisfaction or regret: That new courthouse was a pretty good deal.

To view a tour of the Heman Marion Sweatt Courthouse, visit austinchronicle.com/photos/tour-of-heman-marion-sweatt-courthouse.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.