Another Side of Travis Heights

Residents and Austin Interfaith target blighted apartments

By Lee Nichols, Fri., Oct. 19, 2007

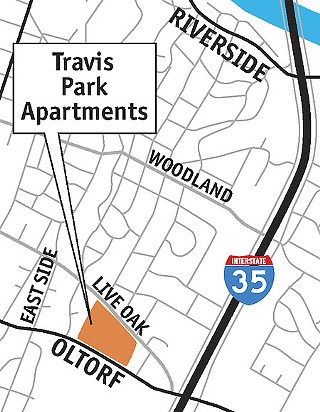

By more than one account, the Travis Park Apartments, just inside I-35 on East Oltorf, are a blight on the Travis Heights neighborhood. The complex fits the stereotype of Section 8 subsidized housing, critics say – an unattractive, graffiti-scrawled complex with maintenance problems and notorious drug-dealing activity. According to the principal of nearby Travis Heights Elementary, a disproportionate number of discipline and academic problems involve kids from the complex. It's even been the site of a murder, last year's infamous stabbing of Esther's Follies juggler Warren Schwartz, aka "Red Ryder." It would seem to be great fuel for a NIMBY movement.

But activists with Austin Interfaith are taking the opposite approach – cleaning up their back yard rather than emptying it. They don't want to rid the neighborhood of the complex – but they do want to rid the complex of its current management. They aren't alone – in a report issued Aug. 22, the Southwest Housing Compliance Corp., an inspection contractor for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, said that the San Antonio-based Lynd Co. "lacks the ability to effectively manage the physical condition and operational needs of the property and the property's Section 8 program requirements" and recommended that "HUD consider requiring the owner to contract with a qualified management agent not affiliated with the ownership entity to correct the ongoing noncompliance issues." (The Chronicle received a copy of the SHCC report through a Freedom of Information Act request.) The Lynd Co. rejects SHCC's analysis, responding that it is fully capable of addressing any problems at Travis Park, and additionally claims Austin Interfaith is just getting in the way.

Despite the management company's protests, the HUD report reinforces what Austin Interfaith – a progressive organizing group (local affiliate of the state- and nationwide Industrial Areas Foundation) that works to unite congregations, schools, and civic organizations around positive social change – has been saying for some time. (See "AI by Any Other Name") The problem, they insist, is not the people in the complex but the level of support they are being given. As evidence, they point to another nearby subsidized-housing complex, the Heights on South Congress.

AI studied a sampling of Travis Heights students from both complexes and found that Travis Park's kids failed the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills test, moved during the school year, had multiple discipline problems, and were absent at about twice the rate of Heights complex children. Those numbers are a focal point of efforts to improve conditions at Travis Park, say AI members who live nearby. "This is part of a big, broad effort to build a community here that we want, a community that is welcoming of all people and their families and their kids and creates a good place for all our kids together to learn and grow and advance," says organizer Steve Jackobs. "That's what this is really about: a strong community."

"We have about 100 or 150 kids, which is at least a fourth of our population at Travis Heights [Elementary], that live at Travis Park," says principal Lisa Robertson. "Prior to the murder that happened that May, we had been trying to work with residents, our parents that live there, on the conditions. ... What ended up happening, because we didn't have a large enough community support, was we got a few things changed, but basically we lost some parents, because ultimately they moved out to a better standard."

Management Strikes Out

The murder of Red Ryder changed all that. As Schwartz's body lay exposed for children heading to school to see, the seeds for a movement were planted. It's a movement that the Lynd Co. says is an overreaction to problems that the company can fix.

Jeff Weissman, a regional vice president for Lynd, said his company is working to address many of the problems that SHCC reported and that onsite and regional managers have been replaced in the past six months. He also disputes some of the report's findings, which are echoed by AI. As for SHCC's suggestion that Lynd should essentially fire itself, he said, "We disagree with that and have expressed those feelings to HUD, and we will continue to manage the property." Lynd gave an official response to HUD and SHCC in September; a rebuttal from SHCC was due on Oct. 8. (At press time, the Chronicle had not received either of those follow-up documents.)

The SHCC report, called a Management and Occupancy Review, rated Lynd's performance over the past year as "Unsatisfactory" (the lowest possible rating) and outlined four major problems:

• a decline in the physical condition of the property since last year's "Below Average" MOR,

• "troubled" tenant/management relations,

• high staff turnover and "ineffective" regional management, and

• remedies to last year's report that "have proven to be ineffective or lacking in appropriate follow-through."

"There are physical issues at the property," says Weissman. "It's almost a 40-year-old property. They mainly relate to the air-conditioning and heating system. ... We're taking action to make all the corrections that they noted."

But only after being badgered into it by citizens' complaints to HUD, says Jackobs. "They would make promises and not follow through. They're not taking us seriously. Our tax dollars are paying these people. ... When we went to HUD [in December], HUD investigated and started holding back their money." It was only then, Jackobs says, that repairs to the property started getting made.

Resident Quisha Boyd, who has lived at Travis Park for about a year, says she asked management to deal with a black mold problem in her apartment repeatedly, but the problem remains, a situation that threatens the health of her three children, two of whom have respiratory problems. "They do not fix things even if you go through the proper procedure," Boyd complains.

Weissman disputes those characterizations. "I feel that Austin Interfaith is asking the residents to go to them to get things corrected," he said, "and not to come to us directly." He said that all residents who attended community meetings over the past year have his direct phone number, and "we respond quickly when asked to do things. Is it always as quick as anybody would like? No. Do things sometimes take longer to get repaired? Yes. But it's our goal to provide good, clean, safe housing for everybody that lives there." Weissman also complained that HUD is slow to send in its payments.

But the problems go well beyond maintenance. The SHCC details crime and security concerns firsthand: "drug activity was observed in [apartment number redacted] the day of the site visit. Upon notification, acting management did not investigate or address the reported drug activity." The complex is supposed to be participating in an Austin Police Department anti-drug program named Operation Strike Out, but "neither site nor regional staff was aware of the program or that the property was supposed to be an active participant." Weissman told the Chronicle that the managers on the day of the site review "were brand-new at the site; they've all been brought up to speed on that since then. ... We don't condone drug use."

Both the review and the Interfaith activists expressed concerns that the private security firm hired to patrol the property, Ranger Security, is not up to the task of ensuring resident safety, especially since Ranger staff is not empowered to make arrests as off-duty law-enforcement officers would be. "We would love to [hire off-duty officers], but we cannot afford to do that," Weissman said. "HUD only pays us so much money. ... If Austin Interfaith would like to pay for off-duty APD, we'll be glad to let them patrol the property. They go for about $35 an hour per man."

Underlying all of this is a feeling of mistrust and strained relations that residents reportedly harbor toward management. The SHCC report says these feelings stem primarily from "[l]engthy delays in responding to maintenance request. ... During the physical review of the property on the day of the on-site review, tenants in four of the 12 units reviewed and two tenants who approached this reviewer while outside, expressed displeasure and frustration with management and length of time/quality of maintenance requests."

Boyd, who also complained that management threw out irreplaceable personal possessions stored in one apartment while she was living in another, described management as "rude" and said, "They treat me bad." Other residents who met with the Chronicle asked for complete anonymity because they fear reprisals if they speak out – a fear that Weissman says he doesn't understand and calls "ridiculous."

Building vs. Community

According to residents and observers, the differences between the Heights and Travis Park are dramatic. AI members describe the complexes' demographics as practically "identical," but "the results that are coming out [of each] are very different," says principal Robertson. "The way they're run is very different. ... Despite the fact that they were built at the same time, despite the fact that they're both Section 8 housing, despite the fact that they have similar bilingual residents, they have similar immigrant residents, they go to the same school, despite all of those things that are in common, you walk into the Heights, and it's a different feeling tone. It's a community. You walk into Travis Park, you don't get the same feeling.

"You go to the Heights, and you talk to the manager, she knows her folks. She can tell which of her elderly residents are in the hospital; she knows her folks. And she knows me – I've been here for five years. You go to Travis Park, even though I've been over there, and the kids know me; [the manager] doesn't know me from Adam. Or she didn't."

"The difference is different owner, different manager, and different management philosophy," says Jackobs. The Heights "has people that spoke both in English and Spanish in the office. They have materials in both English and Spanish. They did not have that at Travis Park until recently. [The Heights has] a swimming pool with swimming lessons that keeps kids occupied. There's nothing at Travis Park." Robertson added, "There's a learning lab where they have a place for kids to go after school to do homework, to learn on a computer."

It's not that simple, Weissman says.

"We got into a detailed discussion on some of the issues with those schools and resources" at community meetings, Weissman says. "We took the stand that while we would like to be stewards of making sure every kid there does their homework and gets to school on time, but if the parents don't care, what can we do? That's not our charge. Our charge is to provide a roof over their head."

Interfaith activists say Lynd's thinking must go beyond that scope. "We'd like the culture to be one of community," says Sean McGuire, a pastoral associate at St. Ignatius, Martyr, Catholic Church. "Of love, joy, respect. Of building together."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.