Mental Health Care Meltdown

Area psychiatric services begin to implode

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Dec. 20, 2002

Austin Police Department mental health officers Art Fortune, Joel Pridgeon, and Sgt. Jeff Hampton can't comment directly on the June 11 shooting death of Sophia King by APD officer John Coffey. They are, however, surprised at the community's response. King suffered from schizophrenia, and she had a lengthy history of interaction with both the police and the mental health system in Austin. As the officers see it, her death should have brought Austin's mental health community and the APD together in a focused attempt to find out what went wrong. But that hasn't happened.

Many people were outraged by King's death, but thus far the anger and its legal aftermath has focused almost entirely on the actions of the police department, while the mental health community has remained relatively undisturbed. "After the incident this summer," says Pridgeon, "I told Art, 'This is it' -- but there was silence."

The officers say they thought that in response to King's death, the larger Austin community, led by local mental health professionals and advocates, would join together to fix the gaping holes in the area's mental health safety net -- a net they say they can't mend on their own. "We thought maybe it would awaken the community, that there is a problem," says Fortune. "This is not necessarily a problem with [officer] training. You can always do more or improved training -- but there have to be other things there, too."

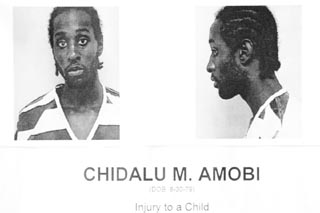

Three months later another tragedy jolted East Austin. According to the APD, on Sept. 6 Chidalu Amobi, 23, entered a house on Clayton Lane and assaulted 2-year-old Khyrian Simms, cracking her skull. Five days later, Simms died at Brackenridge Hospital. Amobi was indicted for capital murder and is awaiting trial in Vernon State Hospital in Wichita Falls. His mother, Angela Amobi, is not convinced that her son killed Simms, but in any case says that his predicament is a direct consequence of insufficient mental health care in Travis County. At 18 her son was diagnosed as schizophrenic, and since that time she has been trying to get him help both through the Austin/Travis County Mental Health and Mental Retardation Center -- the institution legally bound to provide mental health services to the county's medically indigent population -- and through the court system, until the day of Simms' death. In fact, in the days before Sept. 6, she says Chidalu had repeatedly been turned away by ATCMHMR. Angrily, she asks, "What would you think if it were your child?"

In different ways, the deaths of Sophia King and Khyrian Simms cast a harsh light on the shortcomings of the Travis County mental health care system. From the perspective of many observers who know that system well, both deaths were completely avoidable. "Right now we are operating in a crisis system," commented Joe Lovelace, public policy consultant for the Texas chapter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. "Is police officer training necessary? Yes. But more important is a mental health community that doesn't push people off a cliff and onto law enforcement. The problem is that there hasn't been a community vision -- and that's what is stalling this issue."

During the past year, a serious effort has begun to address a major factor affecting public health care in Central Texas: the lack of a hospital district, which could raise funds and coordinate public health care throughout the region. Currently mired in controversy over the Seton Healthcare Network and its plans for a new Children's Hospital, that proposal is expected to go to the voters in some form next year. But the people most directly involved in the current system say that even without a hospital district, Austin and Travis County need to take immediate steps to alleviate the crisis in mental health care, if we are to prevent more incidents like those that took the lives of Sophia King and Khyrian Simms.

The stresses on local providers of mental health care have increased dramatically in recent years. The number of indigent patients entering the Texas Dept. of Mental Health and Mental Retardation system is steadily increasing, while state money allocated for mental health services has effectively flatlined. Local MHMR authorities have little to spend on existing programs, nothing for new ones. Law enforcement officers are now better trained to identify and handle the mentally ill -- but that's also bringing more people into an overcrowded system with radically diminishing resources. Travis County lacks even a single public psychiatric emergency room or crisis stabilization unit where incoming patients could be professionally assessed, stabilized, and referred for further treatment.

All these diminished circumstances have combined to produce a lack of ongoing care that breeds an increasing reliance on less effective and more expensive crisis care. As a result, many patient advocates, police officers, and health professionals conclude that Travis County is in the grips of a full-blown mental health meltdown.

"Don't Ask --"

The current problems with the mental health care system did not happen overnight, points out Texas National Alliance for the Mentally Ill's Lovelace. Lovelace left his career as a private attorney to work for the advocacy group after his son was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Lovelace traces the beginning of the current crisis 40 years back, to the presidency of John F. Kennedy. In 1963, Lovelace says, Kennedy made it a national priority to deinstitutionalize the mentally ill, a trend that continued through the next two decades. But that one step forward, in theory, was coupled with a consequent two steps back. "We closed tons of psychiatric hospitals, but the money didn't follow, and the treatment didn't follow," Lovelace says. "The money went into criminal justice -- and it's déjô vu all over again. So now we are revisiting the same issues; we have more knowledge this time, but we still don't have the public will or the political will to do anything about it."

The Texas Dept. of Mental Health and Mental Retardation runs the state hospital system, including the Austin State Hospital at Guadalupe and 41st. MHMR funds the nine state hospital facilities and allocates funding for each local mental health authority -- in Austin that's the ATCMHMR Center on Collier Street, off South Lamar. For the past three years, the state has allocated to the center nearly $16 million a year -- just over $10 million of it for the center's mental health functions. That's nearly half of the authority's budget; the rest comes from federal Medicaid reimbursements and a combination of city and county funds.

During the same period, however, the number of people in need of services has continued to grow with the state's population. According to TDMHMR numbers, about 3 million Texans suffer from some form of mental illness. Of those, more than 550,000 meet the department's definition of "priority population" -- people who have mental illness and functional impairment, or to put it bluntly, are ill enough to qualify for MHMR treatment.

The local numbers echo the statewide trend. During the fiscal year 2001-02, ATCMHMR served 26,139 people -- up more than 17% in two years. And that reflects only the patients the center was able to accommodate on a stagnant budget -- the increase of people in need is much greater.

Yet the growth in need has not been reflected in state funding. "Every year, every legislative session that I've been here, MHMR is told, 'Don't ask for more money,'" says Dr. Jim Van Norman, the center's medical director of nearly nine years. "To put it very crudely, the department [is] told by the governor's office, 'Don't ask. ...'"

Indeed, mental health advocates place the initial blame for stagnant state funding on the administration of former Gov. George W. Bush. Beginning in 1997, when the Bush administration was advocating a large tax cut, the word went out to state agencies to cease lobbying for more social service spending, including mental health care. With the Bush presidential campaign on the horizon in 1999, that pressure became more intense. Yet such programs are already underfunded in Texas, and nationally the state ranks near the bottom in funding for mental health services.

The numbers are bleak.

Texas has the highest number of people entirely without health insurance, and ranks 44th out of 50 in per capita spending for health care, 47th in mental health care. According to the Texas Criminal Justice Policy Council, at least 29,000 current Texas prison inmates, 106,000 adults and juveniles on probation or parole, and more than 15,000 adults in county and city jails have had at least some contact with the public mental health system. Moreover, nearly 44% of juveniles in the Texas Youth Commission system have a "serious emotional disturbance."

Locally, the largest providers of mental health care are Travis County jails. "If you cut [the state mental health care budget], we will show up somewhere else," says Lovelace. "One [out] of two [mentally ill people] show up in the criminal justice system, and law enforcement can't say no" -- a fact of life in the mental health community. "Half the people that wind up in [the Austin State Hospital] are totally new to us," says Van Norman. "The first contact they have [with the mental health system] is at ASH on an involuntary commitment by the police."

It is a situation that law enforcement officials know all too well: "A peace officer is the only person in Texas who can detain a person against their will," said Mike Sorenson, a mental health deputy with the Travis County Sheriff's Office. Sorenson arrests people often who tell him, "'If you put me in jail, I can get psychiatric care.' That's pretty typical statewide. But what is being overlooked by everybody is what is best for that person."

Imminent Risk

In 1984, the Travis County Sheriff's Office was one of the first law enforcement agencies in the state to certify members of its force as mental health officers, under a state pilot program. Under stringent guidelines intended to balance involuntary detainment with civil liberties, the officers are empowered to detain people without a warrant. Officers may execute a "Peace Officer Emergency Commitment" only when they believe someone is "an obvious and imminent risk of serious injury" to himself or others, and time constraints preclude obtaining a warrant. Under those limited circumstances, law enforcement officers are allowed to detain for up to 24 hours any person against his or her will, including those who have not committed any crime. The principle is simple: identify people in mental crisis and detain them long enough to admit them into the mental health system instead taking them to jail.

For nearly 15 years, the local certified mental health officers were TCSO deputies, responding to both county and city calls. "Uniformed [first] responders ... determine what happened and keep the [situation] sane, and then they notify us," Sorenson said. "We wear plain clothes and drive unmarked vehicles. We get all the information from the officers; we see if they meet the standards according to the [POEC] law."

But in 1999, the APD decided to retrieve the city money from TCSO for the department's own fledgling mental health program. Critics called the decision a mistake based solely on economics, but the move did make some sense. With its significantly larger police force, having certified mental health officers within the APD's patrol ranks could actually increase the department's ability to identify citizens in mental health crises and further the goals of diverting people from jail.

In December 1999, certified APD mental health patrol officers began working the streets, supported by the new Mental Health Unit, staffed by a sergeant, three plainclothes officers, and an administrative assistant. The MHU is charged not only with organizing departmental mental health training, but also with reviewing and following up on all mental health-related police reports, including making in-home follow-up visits, says MHU Sgt. Jeff Hampton: "This area has really mushroomed in the last three years."

Indeed, the mental health business is booming for local law enforcement officers. Since January 2000, according to APD statistics, the MHU has handled 11,589 cases. Additionally, TCSO's Sorenson says that his unit responds to about 2,500 mental health calls a year -- including calls that come from the jail, already at 539 for the year. "We literally respond to more calls than some of the detectives in the central investigations division," says APD MHU officer Joel Pridgeon.

Frequent Fliers

Unfortunately, the heightened awareness of local law enforcement officers has not consistently translated into better mental health care -- and officers feel they are often struggling against themselves. "We try hard on these cases, but we don't work for MHMR," said APD's Fortune. APD's mental health officers say their involvement in mental health services has been frustrating because of the lack of sufficient or coordinated care in the county. The law is clear on what officers must do when detaining someone on a mental health POEC -- what they should do once they have someone in custody is much more uncertain.

Under the law, Austin/Travis County MHMR Center's Psychiatric Emergency Services facility is the "single port" for county residents to MHMR services -- whether or not the person has insurance. When a patrol officer detains a person who they believe requires a mental health assessment, they bring him to PES where, according to Medical Director Van Norman, "The [PES] caseworkers drop what they're doing and attend to the officers first." If doctors feel the patient needs to be stabilized at the hospital, they make arrangements, although the PES does not have the capability to hold involuntary patients. If the person is indigent, they make arrangements for a bed at Austin State Hospital (or another state hospital facility, depending on bed availability); if the person has insurance, PES will make arrangements for a bed at Seton Shoal Creek (or another private facility outside the county).

APD's mental health officers tell a different story. In their experience, PES is so understaffed that patrol officers often wait hours to see medical personnel. (Pridgeon says that once a call hits "the two-hour mark" -- not an uncommon occurrence -- patrol officers will call an MHU officer to take over.) Often, they say, they are expected to determine if the person in custody has insurance -- although the law requires PES to admit the patient in any case.

"Officers are now responsible for the insurance game," says Pridgeon, recounting a recent example -- not an isolated one, he adds -- of an officer who picked someone up who "might" have insurance and neither PES nor Shoal Creek would agree to admit the patient. The officer wound up driving all over town with the guy in the back of his patrol car, while making calls to determine who might admit him.

Fortune sums up the patrol officers' common predicament: If it is easier to book someone into jail than to get him treatment, mental health patients are going to wind up in jail. "Put it this way," Fortune said, "If you had to figure out which one of 30 jails you were supposed to take somebody to, you're not going to take someone to jail. When you make something a confusing mess, you can't expect people to be able to follow it. If I don't understand [the system]," he concluded, "nothing is going to get done."

Van Norman says the PES personnel are doing the best they can, working with five psychiatrist vacancies in 12 positions. Since the hours are "crummy," he says, it has been impossible to recruit enough doctors to staff the facility 24 hours a day -- although PES is open around the clock. With a limited number of inpatient spots available within the state hospital system, and no community hospital with psych beds, finding a place for patients is increasingly difficult. Local beds for medically indigent adolescents are virtually unattainable. "They've been on drive-by," he said. "Right now the nearest child bed for [indigent] kids is in El Paso."

With so many more people in crisis coming into the system, Van Norman adds, there's been a corresponding decrease in the county's ability to provide follow-up care. "We don't have the supports to keep the people engaged in the system." As a result, local law enforcement officers are seeing a lot of repeat customers. "Fifty percent are what we call 'frequent fliers,'" said Sorenson, a situation echoed at APD.

In the glaring absence of an official countywide effort to improve matters, local law enforcement officials are taking matters into their own hands. Since the death of Sophia King, APD's mental health officers have been trying to determine how best to streamline the system. They've traveled to Memphis and Houston to see how "Crisis Intervention Team" programs in those cities work. What they've found, they say, has amazed them.

While the law enforcement portions of each program are essentially the same as in Travis County, the officers say that the mental health authority and the cooperation among the various community stakeholders is completely different. Most notably, each system they've seen has made use of an expanded form of Travis County's PES facility, combining a round-the-clock platform with the capability to hold patients for 24-hour observation, adding a dozen or so inpatient beds, eliminating the need to rely so heavily on the public hospital system.

The funding mechanisms in Tennessee may be different, perhaps precluding a direct translation of Memphis-style facilities to Austin. But Houston's mental health players have direct counterparts here. With such a coordinated effort right in Austin's back yard, APD's officers wonder why Austin hasn't made similar progress. "It's indicative of a lack of resources," said Fortune, "and the way they're prioritized."

"Crisis Intervention" vs. "Fancy Front-End"

Attached to Ben Taub Hospital, just south of downtown Houston, is a squat brick building called the NeuroPsychiatric Center. It is a 24-hour facility run by the Houston MHMR authority, where voluntary as well as involuntary patients (brought in by area police officers) in mental health crises can be assessed by in-house psychiatrists and kept for observation or stabilized before being admitted to an inpatient hospital or referred for follow-up services. The facility is the brainchild of a number of Houston's mental health stakeholders, including the Harris County Judge, members of the Houston Police Dept., Houston's MHMR authority, and advocates from the national advocacy group Mental Health Association.

"Actually, the police department approached MHMR in about 1991 to try to change the process for getting mental health warrants, and that just grew," said HPD officer Frank Webb, who oversees the department's Crisis Intervention Team, Houston's expanded equivalent of a mental health unit. "Then in about 1995, the Mental Health Association got a federal grant to look at mental health barriers. There was a multi-agency task force; HPD was just one of many. And the whole community focused their attention to the CIT [model]."

Among the things the task force identified, Webb says, was the need for a medical facility where officers could drop off patients with little red tape -- the key to a successful CIT program. "It is integral to have a place where you can have a pretty fast handoff," Webb says. "Here [at the NPC] it takes about 15 minutes." The NPC is staffed around the clock with on-site psychiatrists, triage nurses, social workers, medical technicians, and security guards. When officers arrive at a designated entrance, a doctor and nurse immediately greet them, says Dr. Mende Snodgress, the center's director of psychiatric emergency services. Typically within 15 minutes the center has assumed control of the patient, and officers are free to return to patrol. "We have the ability to treat for 24 hours and then to send them to a hospital if that is necessary," said Dr. Avrim Fishkind, the center's medical director. "Without that, you have to send them [immediately] to a hospital, which costs more." Houston's mental health stakeholders say this one-stop efficiency makes their system work. "Let's put it this way," argues Webb. "If it is taking longer to get into the mental health system than it is to get into the criminal justice system, you have a problem."

Fishkind agrees. "You can't have a CIT [program] without an involuntary emergency service to handle the people brought in," he said. "The single biggest problem in Austin is that the money hasn't been [allocated for that]." Fishkind would know: He worked for Austin's MHMR Center under Van Norman from 1996 to 1998 before leaving for work in Washington D.C. and then Houston, where he's been since 2000. "The PES is the same [as Houston's NPC] only in concept, not in function. Not even close," he said. "You have to make it an easy process to take people to medical centers instead of jail. Austin has no capacity for that."

Austin's law enforcement officers agree and lament Fishkind's departure. Fishkind says he left because he was young and "wanted to change the world, and the world wasn't ready to change." But TCSO's Sorenson is more direct: "He had visions of doing [that kind of program] here. He fought tooth and nail and [local mental health agencies] just don't want to share their funds. Why reinvent the wheel?"

To incorporate an NPC-style facility into the current mental health funding mechanism would take some sharing and compromise. The Houston NPC's funding requires around $3 million per year, necessitating extra funds from both the state MHMR and the county commissioners, says Fishkind. "We fund the problem more than all other [Texas] counties combined," said Harris County Judge Robert Eckels. "We've put aside our provincial thinking and our turf wars to try and solve problems. One of the things you see over and over again in mental health is that the only time we get to provide mental health services is when they hit the criminal justice system." That, he says, became unacceptable to his constituents and the county commissioners. In short, Harris County's mental health stakeholders say they could see the cost-benefit of funneling funds into a responsive mental health care system. "We all know that preventative medicine is more cost effective than crisis medicine," said Fishkind. "Usually, even if no one cares about their fellow man, they can understand the cost."

But Van Norman rejects the notion that an NPC-style facility would alleviate Austin's mental health care woes. "The downside in Harris County is that the NPC is almost bleeding the MHMR dry," says Van Norman. "It's so attractive to leap at the NPC -- 'That'll fix it.' But it's an unbalanced system. It's fancy front-end." To Van Norman, the most important thing the county can do right now to improve the overall delivery of health services is to create a hospital taxing district.

No one could agree more than Probate Judge Guy Herman, who is on the front lines in the fight for a hospital district. The mental health care system, Herman says, is "broken," and that in part convinced him to push for the district. "I don't see any other way out of it for Travis County," he says. But Herman agrees that an NPC-type facility is invaluable. "The biggest fracture is that we don't have an inpatient placement facility for kids and adults."

And Van Norman's position is also disturbing to Houston's mental health community, who say that while expensive, the NPC and its components are necessary to make significant progress in serving mental health care consumers. Said Eckels, "I would argue that we are not 'bleeding' funds from the system. I can't say that is entirely inaccurate. But I can say that [NPC] meets a critical need -- and it is more than just a showpiece. It fills a huge, unmet need in the city." HPD's Webb says he finds Van Norman's take on the NPC "a little odd." "There are already budget shortfall problems, and those problems are going to get worse," he said. "For a lot of people, calling the police is their last resort. I wish it wasn't that way, so they wouldn't have to go into crisis out on the street. But that is what is happening."

Falling Through the Net

Webb's judgment appears confirmed by the recent tragedies in Austin. A case can readily be made that the death of Sophia King and the infanticide charge against Chidalu Amobi were direct results of the failure of the county's mental health safety net. King was initially committed to the Austin State Hospital on a POEC, where she was subsequently diagnosed as schizophrenic. Yet it appears she was never connected to the local MHMR for any follow-up care. "She was never even assigned a social worker," said Texas Civil Rights Project Executive Director Jim Harrington, who has filed a wrongful death suit against the city on behalf of King's family. "Can you believe that?"

In the case of her son Chidalu, Angela Amobi argues, the oversights of the ATCMHMR are even more disturbing. During the first week of September, she and her son were at the PES facility no less than three times, trying to get medicines to control his schizophrenia and trying to get a psychiatrist to support her quest to get him committed to ASH. "But they refused to see him," she said, "and [the doctor] refused to sign the paperwork [to have Chidalu committed]. He was begging for help, and he was ignored."

While no one is willing to speak candidly about either of the specific cases, ATCMHMR Executive Director David Evans insists his agency is doing the best they can with the little they have. "Obviously when you are trying to do something for everyone, you can't do everything," he said. "We are wide but thin." Van Norman is slightly more forthcoming. "There is an increase in occurrences that are preventable, because we are stretched so thin," he says. "I doubt anyone has been turned away, a no-room-at-the-inn, bolt-the-door kind of thing."

What happened with Amobi, as well as King, will likely be settled in court -- and theirs are not the only cases. According to Beth Mitchell, a senior attorney at Advocacy Inc., which advocates on behalf of disabled Texans, a civil lawsuit seeking a declaratory judgement on behalf of at least a half-dozen mental health consumers is imminent. The plaintiffs -- all within the same high-risk for entering and re-entering the mental health emergency services cycle -- are asking a judge to declare exactly who, state or county, has the legal responsibility to provide funds for "wraparound," coordinated mental health services.

"We've seen a revolving door because of a lack of community services," said Mitchell, but there are conflicting statutes within Texas law. One provides that the county MHMR authorities are financially responsible for all medically indigent mental health care, while another provision suggests that the county authorities are only required to fund services up to the available funds provided by the state. "So, is it county or state? Who do we really bill?" Mitchell asks. "Who is going to pony up to make sure that people get served?" ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.