The Battle of Washington's Bulge

The textbook wars make a casualty of Washington Crossing the Delaware.

By Michael King, Fri., Nov. 22, 2002

George Washington and his ragtag Continental Army may have heroically defeated the mercenary Hessians at Trenton in December 1776, but the old soldier is now in danger of being permanently unmanned -- by the combined forces of political neo-Victorianism and commercial publishing. In one of the silliest but unfortunately representative episodes of the recurring controversy over state textbook adoptions, the best-known artistic representation of General Washington in action -- Emanuel Leutze's 1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware -- has been intentionally emasculated in history textbooks because bluenoses and bureaucrats are afraid students might imagine George Washington had a penis.

Last week -- after politicized arguments over "factual errors" and "omissions" and a hurly-burly of last-minute revisions by publishers desperate to capture the Texas market -- the State Board of Education gave its final blessing to the social studies textbooks to be used by Texas students for the next several years. Among the eighth-grade American history textbooks considered for state adoption were Prentice Hall's The American Nation, Holt Rinehart Winston's Call to Freedom, and Glencoe/McGraw-Hill's The American Republic.

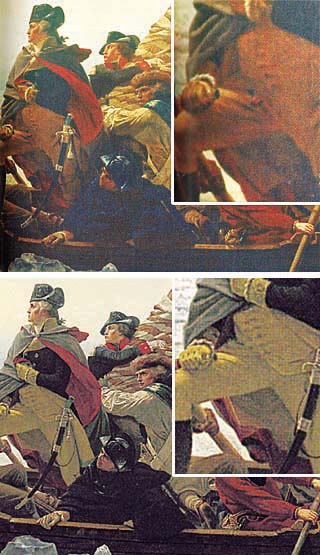

In the three books, Leutze's legendary painting -- a masterpiece of 19th-century romantic nationalism, and a piece of American history in its own right -- reflects the scars of the textbook wars. The original painting, in the epic proportions of 12 by 21 feet, portrays an idealized Washington fearlessly standing in a rowboat guided eastward by his men through the ice-filled, treacherous waters of the Delaware River, while behind him stand two soldiers holding a furled U.S. flag. (The actual journey took place in the predawn hours of Dec. 26, but Leutze shows the soldiers brightly illuminated by the rising sun.) Washington wears a tri-cornered hat, a cape, and a sword at his left side, and his right hand is thrust forward on his right hip. That's also where the trouble lies -- just behind Washington's right hand, at the crotch of his pants, a shaft of light falls on the ornamental, reddish fob of his pocket watch (one of the necessary accoutrements of an 18th-century gentleman). The novelist Henry James would later recall his youthful memories of seeing the painting for the first time, describing "a wondrous flare of projected gaslight ... with the effect of a revelation to my young sight of the capacity of accessories to 'stand out.'"

On the much-reduced scale of a textbook, the watch fob is difficult to distinguish -- and viewed with a feverish, bureaucratic, or juvenile eye, the red fob might be misapprehended as the rosy tip of Washington's genitalia. In 1999, that scandalous possibility so alarmed Guy Sims, the superintendent of schools of Muscogee County, Georgia, that he had teachers' aides spend two weeks re-painting by hand more than 2,300 fifth-grade textbooks to eliminate the offending detail. "I know what it is and I know what it is supposed to be," said Sims. "But I also know fifth-grade students and how they might react to it." The school officials of neighboring Cobb County were not so delicate -- they simply ripped the offending page out of all their textbooks.

By the time the books reached Texas this year, the publishers had apparently gotten the message from Georgia. Of the three books, only Prentice Hall's faithfully reproduces Leutze's original, watch fob and all. The Glencoe/McGraw-Hill text (not pictured here) darkens and distorts the colors of the original to the point that all small details are rendered invisible -- avoiding all danger of "wondrous revelation." Holt's Call to Freedom is the most deceptive: It prints and represents as Leutze's painting what is in fact an inferior, highlighted copy painted by his student Eastman Johnson for the purpose of making engravings -- and thus eliminating all ornamental details like watch fobs.

Glencoe/McGraw-Hill officials did not return calls requesting comment. Rick Blake, Holt's vice-president for communications, responded that Call to Freedom simply reproduces "Eastman Johnson's version" -- and was somewhat abashed to hear that the text in fact credits the painting to Leutze and notes that it "now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City," as Leutze's does. (This "factual error" was not caught by the eagle eyes of the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation.) It's not the first time Blake has had to defend Holt's preventive prudery; earlier this summer The Daily Texan's Patrick Timmons reported that a Holt high school economics textbook drapes loincloths on photos of the naked male statuary decorating the New York Stock Exchange. When the Texan story went national, Blake told reporters that the publisher had simply decided that "nude figures on the cover of a high school textbook was not such a good idea."

Though Wendy Spiegel, spokeswoman for the textbook division at Prentice Hall, had heard rumors of criticism of her firm's unaltered reproduction, she is unapologetic about maintaining the integrity of the Leutze painting. "We will not alter the painting," Spiegel said. "We will make certain the reproduction is accurate and true [to the original]." Harold Holzer of the Metropolitan Museum said the museum tries to ensure that "when they credit the Metropolitan, they reproduce [the painting] accurately." Presumably, the Met can ask that its name be removed from inaccurate reproductions; Emanuel Leutze has no such recourse.

When the list of SBOE-approved eighth-grade social studies textbooks was released last week, all three texts were on it. However, the Chronicle has learned that reviewers for at least one Texas school district have already expressed dismay at Prentice Hall's too-accurate reproduction of Leutze's painting -- making it likely that at least some Texas schoolchildren will be spared an embarrassing encounter with Washington's fob, as well as Leutze's masterpiece.

"The story might seem ridiculous," commented Samantha Smoot of the Texas Freedom Network, which works to counter the influence of the religious right in state government. "But setting aside the important issue of the rights of artists and the integrity of an original artistic image, even more troubling is the willingness of publishers, under the pressure of the textbook review process, to engage in self-censorship."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.