Chain Reaction

Downtown's Bricks-and-Mortar Projects Hammer Home New Concerns

By Amy Smith, Fri., Dec. 24, 1999

Years ago, you could stand inside Waterloo Records and look out across a dingy row of low-slung buildings to a skyline that neatly defined Austin, Texas, circa 1989. John Kunz had just moved his record store to the newly renovated little shopping center at Sixth and Lamar, and the neighborhood of car lots and salesmen in pointy-toed cowboy boots was starting to grow on him. He liked walking up the street to the Sweetish Hill Bakery for coffee and pastries, and, over the years, he admired how Wiggy's, the neighborhood stop for a nice bottle of wine or a pint of Jack, matured into a thriving enterprise. There were a lot of things Kunz liked about Sixth and Lamar, but the view of the skyline, now that was sweet. Eventually, though, the vista went the way of Capitol Chevrolet's used trucks across the street. The open-air lot was replaced by the tall, modern limestone building that houses Whole Foods' flagship store and BookPeople, and that building's top-floor offices commanded a pretty nifty view of downtown -- until GSD&M obscured the picture when it built its big "Idea City" next door (flood plain be damned), on the site of the old McMorris Ford dealership. The last person to inhabit the McMorris site before a wrecking ball took it down was former mayor Bruce Todd, who ran a bruising re-election campaign out of the vacant showroom that peered out through a dusty plate glass window onto West Sixth Street.

Anyway, the domino effect of the diminishing skyline is how Kunz explains Sixth and Lamar's rise in popularity over the last decade as the car dealerships and body shops picked up one by one and migrated south to a new settlement on the I-35 frontage road. This shift in the wind was due in large measure to two people: former mayor Roy Butler, who sold off a bunch of his property where car lots and tumble-down buildings once stood, and Scott Young, who got his start with Roger Joseph developing the 600 Lamar shopping center and then went on to swing the Whole Foods and GSD&M deals.

"Scott Young is the father of Sixth and Lamar -- and I'm the grandfather," proclaims Butler, an old-school wheeler-dealer who's had his hand in this neighborhood's properties since the Fifties. "Sixth and Lamar," Butler explains, "used to be a scrubby strip of used cars leaking oil and antifreeze. Now it's turned around 180 degrees, and it's beautiful."

The Big Picture

In a longer view, the intensity of activity in this southwest downtown neighborhood is but one example of how Austin has crawled out of the empty pockets of the Eighties to rebound with a vengeance in the Nineties. Now the suburbs are passé; downtown is the darling of developers eager to capitalize on the city's commitment to turn the Central Business District into a 24-hour downtown. "A new building in the suburbs looks like any other building in any other suburb," says developer Tom Stacy. "But if you do a building on Congress Avenue in Austin, Texas, that's a meaningful and very fulfilling experience."

Today, every downtown neighborhood -- from Sixth and Lamar, to the West End/Warehouse District, to Congress Avenue, to the Convention Center, has a construction project under way, or is poised to see a project break ground soon after the new year (see p.26). Clearly, these are heady times for Austin -- wallet and spirit. Consider the current state of affairs:

But lest we get carried away in all the glitter and hype, here are some gloomy facts to bear in mind:

Big-Box Retail Arrives

It's 10 o'clock on a dazzling Friday morning in October, and David Vitanza is standing before a giant concrete wall with a big smile on his face. For the past 20 minutes or so, he's been fairly serious and intense as he walked through the dim shell of a building at Fifth and Lamar, pointing out where Office Max would go, where the entrance to Starbucks would be, along with Austin-based Earful of Books and Powerhouse Gyms International out of Farmington Hills, Michigan.

But now, back out in the sunlight, Vitanza is starting to loosen up a bit. "This," he explains, adjusting his hard hat and pointing to the smooth slab of concrete, "this is an unusually tall tilt wall building. And it's a very successful experimental technique," he notes, referring to the graceful embedded archways, carefully crafted by American Constructors. "This kind of stuff is so exciting to watch," he says, gazing up at the slab. Admittedly, his enthusiasm is a tad infectious. As he explains the wall of concrete's intricate detail, the slab begins to takes on a smooth, flowing look, gray and sincere in its 80,000-pound hulk. "I know it's weird," Vitanza offers apologetically, "but I just like construction."

When he snaps out of the marvels of tilt walls, Vitanza is once again all business. He and his partner Brad Schlosser -- together, the two make up Schlosser Development -- are nearing completion on the first phase of an $80 million, 525,000-square-foot project that will bring to southwest downtown not only the above-mentioned businesses but a Target, a 16-screen Sony/Loews theatre, and a number of specialty shops and restaurants. It is a huge undertaking that Vitanza and Schlosser have worked on for several years. But it is not without its detractors. While Vitanza claims he's heard no ill remarks about the prospect of Target's presence downtown, many who live and work in the neighborhood, and even some developers, wince at the thought of a national discount chain moving into one of Austin's cooler neighborhoods.

By contrast, developer Evan Williams' project across Lamar from the Schlosser site at Sixth and Lamar is much smaller, at 38,000 square feet, and is aiming for an altogether different niche market. Tenants include two Austin-based businesses -- By George clothing store and Mecca, a gym and day spa; and Houston-based Cities -- sort of a mini-Crate and Barrel store, according to Williams. The project, scheduled to open in March, will also hold some office space geared toward the tech persuasion. Similarly, on the west side of the street at Fifth and Lamar, local entrepreneur Whit Hanks recently completed work on a little shopping center of high-end boutiques, which were, ironically enough, converted from a Capitol Chevrolet body shop.

So will a national Target store tarnish the neighborhood's image? Vitanza doesn't think so. For his part, he says he was "jumping up and down" when Target signed on to the project. The Minneapolis-based chain has spiffed up its image over the years -- a makeover that has included rumbling out of suburban trenches across America and laying down stakes in urban malls in places like Miami and San Diego. Vitanza says his company had tried to recruit Nordstrom's and Macy's, but neither department store was willing to commit to a large financial investment in new real estate. So then it was Target -- and its healthy credit rating -- to the rescue.

On the bright side, even many critics of the chaining of Sixth and Lamar agree that if anyone is capable of pulling off this type of project -- and perhaps even managing to minimize Target's presence without slighting Target -- it's Schlosser, a company that has won the respect of a number of developers around town. "If Sixth and Lamar is going to change, then I think they're the ones to do it," Kunz concedes. Moreover, the prospect of walking to a movie theatre on this end of downtown is winning applause all around. "Personally, I love the idea of walking across the street to go to a movie," says Kunz, "but in terms of a Gap or something like that being there -- I prefer to go out of my way to support independent businesses."

Vitanza, meanwhile, is keeping quiet on specifics about the remaining tenants he's recruited, or is trying to recruit, for the second development phase, which is scheduled to get underway in the spring, just as Office Max is throwing open its doors. But it will be interesting to note the ratio of local businesses to chains.

The Little Guy

That's not to say Schlosser Development isn't beating the bushes trying to recruit some local tenants. But one local that won't be moving to Sixth+Lamar is Waterloo Records. Kunz says Vitanza approached him about defecting from his 600 Lamar quarters, but the record store owner declined. "We were concerned about the size and the scope of the project," Kunz says. "When we moved here, there were a lot of folks who thought we were getting too big for our britches. So of course we were concerned about how our customers would react if we moved across the street."

For now, Waterloo is staying put on a long-term lease, but that doesn't eliminate the possibility of a national record store taking up residence in the Sixth+Lamar project. (Early conceptual drawings indicated a Virgin Megastore in the complex, but Kunz says the developers have assured him that that was merely an artist's conception of what might be there.)

The same concern holds true for Amy Miller, the CEO of Amy's Ice Cream. While Kunz chooses his words carefully when discussing the new neighbor, Miller is less charitable. Like Kunz, Miller opened her ice cream store -- her second -- in 1989 at the 600 Lamar shopping center, along with other locals -- Emeralds (which later outgrew the site), Waterloo Ice House, Avalon, and Sparks. Miller is firmly committed to the neighborhood that she fell in love with shortly after moving to Austin in 1984. "Back then I enjoyed going to some of the shops along West Sixth Street," she says. "It was a real nice area, but it did not have critical mass."

Not until the creation of 600 Lamar, at least, whose tenants already had a loyal following. Noting how the Sixth and Lamar landscape has changed over the years, Miller admits that she's not a big fan of this particular type of progress. "I have real mixed feelings about it, because I'm not very growth-oriented. I mean, all of that concrete," she says, referring to the same concrete that Vitanza went gaga over a few days earlier. "It's just not Austin," she continues. "It's not quintessential Austin. Projects like that are pulling out all the magic."

Times have changed for the ice cream trade as well, with competition melting away some of Miller's business. "Our sales have plateaued," she says. "We may look really busy, but it's getting tougher to sell $3 ice cream. And rents are going up, so I dread the day when I have to try and sell $5 ice cream."

The Olden Days

If Miller thinks things are sorry now, it could have been a lot worse, for 600 Lamar very nearly became the home of a 7-Eleven convenience store in the mid-Eighties. That was when land owner Roger Joseph, a third-generation Austinite, and Scott Young, a 25-year-old developer still wet behind the ears but learning fast, stepped in and intercepted the deal -- at the height of the real estate bust. Until Joseph, who hails from a long line of property owners, bought the site in 1986, the list of prior owners read like a Who's Who of land barons.

Roy Butler owned the property before selling it to Lowell Lebermann and George Coffey, who in turn sold the land to old politicos Ben Barnes and John Connally. Then the Barnes and Connally venture went broke, so Remington Savings & Loan assumed ownership of the property, until the S&L went the way of other S&Ls -- belly up -- and Joseph sealed the land deal.

Once it was clear 7-Eleven was out of the picture, the first order of business was to renovate the existing buildings on the property and try to rustle up some tenants. "I had an idea of what type of tenants I wanted to see in there," Young recalls, "so I grabbed a Chronicle and started my search." The real estate bust didn't help matters much. "People would drive by and honk and shake their heads," Young recalls. "They thought we were crazy -- and really stupid for signing up small businesses."

Whether it was perseverance, the gods of real estate, or just plain stupidity that worked in their favor, the Joseph-Young effort paid off. By 1989, the center was filled with firmly footed local businesses. With the exception of Emeralds, which relocated when it ran out of growing room, the original tenants remain, and the parking lot is nearly always full.

Once the 600 Lamar site was off the ground, Young started looking around for more homegrown tenants to relocate on fertile, vacant ground directly across the street. Butler owned that property, too, and even had a Lincoln-Mercury dealership on the site at one time until he got out of the car business, selling the dealership to Lebermann and Coffey. He kept the land, though, until the early Nineties, when the next wave came along.

Initially, HEB had an option to buy Butler's land, with the idea of opening its Central Market on the site. But the food store, even after two years, wasn't making any move to buy the land, and Young was in a hurry to turn it into gold. He convinced Whole Foods CEO John Mackey that the site would be perfect for him to buy and lay down stakes for a new store, since the organic shop up the street was outgrowing its modest quarters. Pretty soon, Mackey's friend, Phillip Sansone, the founder and former CEO of BookPeople, had agreed to move out of the Brodie Oaks site down south to lease the east end of Mackey's Whole Foods development.

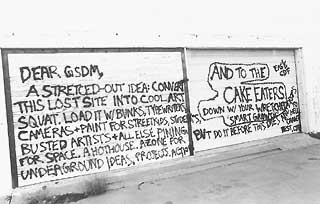

But HEB still wasn't budging. With the land option pending, Young went ahead and negotiated a backup agreement on the property in the event the HEB deal fell through. Then he waited. Eventually, HEB dropped out of the Sixth and Lamar deal and -- voila! -- the land landed in Whole Foods' lap. From there, it was on to the next mission -- negotiating a suitable deal for GSD&M, which had been fishing around for a downtown site, having outgrown its offices on Capital of Texas Highway. It wasn't long before Young had the ad company locked in next to Whole Foods.

"So you see," Young continues, "the 600 Lamar deal just set off a chain reaction of development downtown." Butler is not so quick to hand the starting-point credit to the folks at 600 Lamar, though. "It was when Whole Foods moved in," he counters, "that's when things really started to pick up."

At any rate, Young goes on to say, "It comes down to the fact that small mom-and-pops are really attractive to me. I just prefer working with them, more so than the big chains." But like others in the neighborhood, Young worries about the demise of the independents. "It would be terrible," he says, "if all the national chains came in and replaced the locals."

As Austin's "preferred growth corridor" continues to build up, trying to define Smart Growth is like trying to define art, or pornography. Putting big-box anchor tenants at Sixth and Lamar may seem smart to some people, and dumb to others.

"Do we want the homogenization of Sixth and Lamar?" Kunz asked rhetorically the other day. This is a man who not only spends a lot of time reflecting on the evolution of record stores -- from vinyl to CD to digital -- but also ponders the future of the city and the neighborhood he loves.

"It's a strange deal because on one hand, I'm all for having a nice, compact city, but I'm just hoping that Austin won't grow haphazardly when it comes time to doing denser infill -- and then seeing the way density doesn't work," he says. "And where this is taking us, I frankly have no idea." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.