Elementary Rights

Clearing the Red Tape

By Melissa Sattley, Fri., May 7, 1999

David Lane, director of the INS Criminal Investigations Unit, says he wouldn't mind moving. But for now the agency has signed a six-month extension on its current lease. "I'm not hard-headed, and I'm open to any suggestions," he offers diplomatically. He likes the fact that the office he looked at in the Federal Building is at least twice the size of his current 300,000-square-foot office. But Lane also states that his willingness to move has little to do with the community protests or the steady flow of inquiries from government officials in Washington. "The unit has expanded in size by at least 30% within the last couple of years -- and we need more room," he says simply.

The only problem is, the INS doesn't want to pay for the relocation, citing severe budget cuts in operational costs. Lane says moving into the Federal Building will require the INS to build new detention cells in the basement, along with relocating computer LAN lines.

This year, the INS was allotted a $3.9 billion budget, and INS commissioner Doris Meissner said in February that the agency will spend $21.9 million in Texas to build new offices. Meanwhile, "We are in limbo," says Lane. "The ball is way up there now and the decisions are being made at a higher government level."

Myron Johnson, a customer service representative for GSA, who is helping locate space for the INS, says he isn't surprised that the agency thinks GSA should foot the bill for the move. He says it isn't unusual for one federal agency to try to get another to pay its costs. "Which agency actually pays for the move will have to be negotiated," he says. "Either way," he adds, "the taxpayers will ultimately pay for the move in the end."

Pablo Ortiz, who has spearheaded the campaign to get the INS to move out of his neighborhood for the past two years, thinks the INS is just dragging its heels. "They belong in the Federal Building -- it's big enough, and away from residential areas. The problem is the INS wants to spend money on expanding at the border and not on cleaning up its old messes."

A History of Protests

|

|

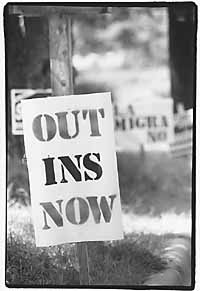

"My son couldn't have been older than five years old in this picture," she says. "He's nearly graduated from high school now, and the INS office is still there." Nanyes says she remembers an INS official from San Antonio telling the protesters they were going to move the office out of her neighborhood. Satisfied, they packed up their protest signs and went home. But in a matter of days the INS was back in business. "It was a big deal in the neighborhood and we went to several meetings about it," she says. "But they just moved all their cars and hid out for a little while," she says, "then they opened up their doors again after they were sure we were gone." Ray Dudley, who at the time had just started as INS' public affairs officer, says the INS never made any sort of promise to move. But Dudley also claims that he can't recall there being any protests at all, despite the fact that the local TV news and the newspapers covered it at the time.

Liz Fernandez, who has two daughters that went to Galindo, remembers the protests well. "We found out that the INS was coming in while the school was being built -- but we never could get anything done about it.They told us it was a service center, not a detention center. We went to several meetings and it was a big issue for a while." Fernandez says she never let her daughters walk home alone when they attended Galindo. "I was concerned because it seemed like no one was really checking on anything," she says. "And kids would see people going in and out. You never knew what kind of people were in there."

INS' Lane is angered when he hears about the neighborhood fears about security at his office. He says there have never been any major incidents, and he adds that his office has never had any complaints from the school or the youth shelter next door to it. And both Richard Gonzalez, who has been the principal of Galindo for the past three years, and Duncan Cormie, director of Lifeworks youth shelter, which is located between the INS and the elementary school, say the INS has been nothing but a good neighbor. "I wasn't even aware of the INS office until the community protests," says Gonzalez. After the latest spurt of protests began in 1997, he says, Lane gave him a tour of the facilities. "It seemed perfectly secure to me," says Gonzalez.

Yet Gonzalez admits he's not pleased with the concept of his school's neighbor being a processing center for criminals, though he doesn't think it poses much risk to his students. "On occasion the students might see something -- men being walked into the facility from a van," he says. "But I have to speak for the school and it would be unfair to single out the INS office as a problem. They've been great neighbors during my tenure."

Pablo Ortiz says Galindo Elementary has not been in support of GENA's protests against the INS. "The principal is new to the community, and he's not in favor of our protesting," he says. "And that's fine; we don't want any animosity between the community and the school."

Despite the low profile that the INS' Criminal Unit tries to keep in the neighborhood, minor incidents have been known to crop up. Once, says Lane, an INS bus was parked out front and a prisoner tried to kick out a window and escape. Another time, says Donna Bliss, the food service coordinator at Lifeworks, she was startled by a man with a shotgun crossing the parking lot. Bliss was happy to find that the man was a federal agent and not an escapee. "For a moment I didn't know whether to duck or run," she says.

Unlikely Neighbors

Besides the INS facility, there have also been some minor incidents between Lifeworks -- a teen shelter housing youths at risk -- and the elementary students. Once, some of the teens from Lifeworks chopped down a tree in front of Galindo. Another time, after the Junior League had dropped off some Christmas fruit baskets at the shelter, the teens threw apples and oranges at children on the playground.

Parents in the neighborhood support the shelter, which has been on South Second since the early Eighties -- long before Galindo Elementary was built. But at the same time, they also question the rationale of an elementary school being placed next door to a teen emergency shelter and an INS Criminal Investigations Unit.

Duncan Cormie, director of Lifeworks, agrees that it is a strange match. "I admit it's odd to have these three programs side by side, but we've never had any major incidents," he says. "I'm actually shocked that there's been so few problems."

Cormie says the INS has always been cooperative and have even helped some of the youths in his program reunite with their parents. But he also says he can understand why parents might be concerned. "I'm a new parent myself," he says, "and there are so many things to be scared of now." Cormie thinks the INS would be better served in a larger facility downtown."They need a place with larger streets and more parking; it's hard to back a Greyhound bus into this parking lot." Cormie, who works with many Hispanic youths at the shelter, also points out that the INS presence could be self-esteem damaging for both the teens at his shelter and the younger kids at Galindo. "I think it does affect the kids to see people in handcuffs -- and this is an issue for society as a whole," he says. On any night on TV you see shows like COPS, and most of the criminals they'll show are people of color."

City Has No Jurisdiction

Greg Guernsey, an Austin city planner, says that because the INS is a federal agency, it doesn't have to follow city zoning regulations. He says the city works closely with the school district regarding zoning problems such as liquor stores being too near to schools. But with a federal agency, there is nothing that either AISD or the city can do. "The school board could pass a resolution and write letters of concern to politicians -- but that's about it," says Guernsey. "In the end the INS can do what it wants, and we can only voice our opposition."

And that is exactly what the neighbors and parents in this South Austin neighborhood have been doing since the INS opened its doors in 1986. This time they say they won't give up until the INS leaves for good. "They never have taken us seriously," says Liz Fernandez. "The INS figured they could move here because we were a minority and low-income neighborhood and not empowered politically."

"We tried all the political avenues, and they failed last time," says Pablo Ortiz, referring to the protests in 1986. "But no way we will drop the issue this time."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.