https://www.austinchronicle.com/news/1998-12-04/520739/

Southern Living

A Vested Interest

By Erica C. Barnett, December 4, 1998, News

|

|

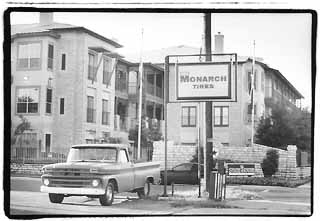

Most residents and business owners agree that change is inevitable; what they disagree on, however, is how best to manage it while preserving the unique character of their neighborhood. One faction, led by the South Congress Coalition, believes that small businesses and residents will prosper only if crime and prostitution can be eradicated from the area; another, headed largely by members of the Dawson Neighborhood Association, which recently completed the city's first neighborhood master plan, believes that economic expansion itself will ultimately drive off crime and revitalize the area.

No More Pawn Shops?

To that end, Dawson members have proposed temporarily restricting certain types of businesses -- primarily strip joints and adult theatres, pawn shops, drive-through establishments, and auto shops -- from locating on certain areas of South Congress, South First, and Oltorf; in the future, neighborhood residents would also like to include South Lamar in the plan. "These areas are going to get developed regardless, but if we can steer it toward businesses that enhance the neighborhood, we don't want to discourage that," says Donald Dodson, a Dawson NA member. The plan, which was approved by the planning commission in March and will go before City Council this Thursday, Dec. 3, would impose restrictions on some three dozen types of businesses for a six-month period, after which, according to city neighborhood planner Robert Heil, the city will examine "how much these businesses contribute to or detract from the [other] businesses in the neighborhood."

But some in the area are wondering whether the proposed restrictions, which apply to everything from off-street parking to gas stations to veterinarians, go too far. Jim Lloyd, president of the South Congress Coalition, which has focused its efforts primarily on fighting crime along the South Congress corridor, says that coalition members had several reservations about the neighborhood association's initial plan. "At the time we thought it was too restrictive. A drive-through could be a dry cleaner," he says. But, Lloyd acknowledges, South Austin already has more than its share of pawn shops and car washes, particularly along far South Congress and South Lamar. "When you have a lot of pawn shops in the neighborhood, there's a feeling that it increases crime. That's something we need to resolve."

Indeed, crime -- particularly drug use and prostitution -- has hardly vanished from the area, as some enthusiastic South Congress denizens might assert; instead, many residents say, it has simply changed location, to the area around Ben White and the neighborhoods west of Congress Avenue. "A lot of the prostitutes that left [South Congress] came to our area because the police were closer in" to downtown, says Dodson, who lives near St. Edward's University. But as new businesses locate in the area, Dodson believes, economic revitalization may spur a slow exodus of crime and prostitution from the area; already, he says, the process has "slowly but surely" begun.

Real Estate Bonanza

Businesses aren't the only ones looking to locate in South Austin; there's also an influx of new residents, both home buyers and renters, wanting to cash in on the area's reputation as a cheap, friendly, eclectic neighborhood. The vacancy rate in South Austin, according to Ryan Robinson of the city's Planning Department, is less than 3%; at the upscale State House Apartments, formerly Jefferson on Congress, every single unit is leased or occupied. The city, meanwhile, issued almost 100 permits for new home and apartment construction in the last three years. But South Austin's extraordinary popularity may be leading to the demise of what makes property in the area a hot commodity -- its diversity, funkiness, and relative affordability.

In fact, according to both official figures and anecdotal evidence, many parts of South Austin are already off-limits for budget-minded home buyers and renters. Median house prices have mushroomed in recent years, increasing from just over $99,000 in 1996 to $122,270 as of this September, says the Austin Board of Realtors' Susan Moore. Similarly, Jim Holland, owner of Eco-Wise on W. Elizabeth Street off South Congress, sees ballooning taxes and property values as a sign of full-blown gentrification. "This area's done in a lot of ways. People can't afford to move here any more," he says. "It used to be you could go back in this neighborhood and find a decent house for $30,000; now that same house will cost you $160,000."

And as property values are increasing, property taxes are also taking an inevitable, parallel upward climb. "There's a big tax protest movement among people who are not in [South Austin] as investors -- people who have lived there," says Cinema West buyer Henry Benedict, who owns several rental properties in the area. "The average tax down there on my properties is $1,400 a year . ... My base rent goes up [each year] by at least $100 a month because of taxes."

That's in keeping, residents and property managers say, with South Austin's skyrocketing rental rates, which are currently about a dollar a square foot -- comparable to prices in costly Central Austin neighborhoods like Hyde Park -- throughout most of the area. According to a rental agent at Property Max, an apartment locating service, rents go up about every two months in this hot-market area, and owners aren't offering any specials. At the State House Apartments, rents are $1.20 a square foot, and rising fast. That, according to State House apartment manager Tom Lumley, is "outrageous ... I'm shocked at some of the prices, because unlike other cities up north where the salaries keep up with costs, the salaries in Austin aren't there." Nevertheless, says Lumley, the apartments -- now managed by a company called LBK Management in Irving -- have seen two rent increases in the past four months, with at least two additional hikes scheduled for 1999.

With South Austin's cost of living higher than it's ever been, many long-term residents are wondering what sort of people will be able to move there in the future. Donald Dodson says the diversity of his neighborhood, bordered by Oltorf to the north and Ben White to the south, is being threatened by the area's rapidly increasing housing costs. "A lot of the older Hispanic couples who raised their kids here are being adversely affected because they're not planning on moving but their property taxes have gone up," Dodson says. "In many ways it's still an old, funky neighborhood -- old hippies, bohemians, old Hispanic couples, and bikers. None of them are really rich. ... The type of diversity that's good, where you have several levels of income in one area, I'm afraid you're going to lose."

As of the most recent census, South Austin's population was 50% minority, with 25% living below the poverty line. But if residents' common conviction that the area is being "yuppified" hold water, these demographics are likely to have changed by the time the 2000 census rolls around.

Benedict, who lived in South Austin in the 1970s, believes that the area's shifting demographics are a sign that the neighborhood is changing for the worse. "It's still a very friendly and cohesive place, but it's not as Hispanic and working class as it used to be," Benedict says. "It's a lot more yuppie and high-tech and Anglo and there are very few families. ... There are not kids in the street any more." Instead, he says, the area is being overrun by people from outside Austin, who have "a much higher tolerance for the inconveniences of city life," and so might not mind the traffic, overcrowding, and expense which often accompany inner-city revitalization.

Moreover, as property values skyrocket all over South Austin, business owners who rent property in hot-market areas are starting to feel the burn of stratospheric rent increases. At New Bohemia, whose new location is one-quarter the size of its former Hyde Park digs, business is increasing just steadily enough to keep up with rent, which owner Alexandra Renwick says is about twice as much as she used to pay. Eco-Wise, a small retail establishment where nontoxic paints and pesticides bump up against organic cotton sheets and recycled glass objets d'art, recently moved from a tiny space on South Congress to a much larger building a block away. Owner Holland says that although his rent "at least doubled" at the store's South Congress location, that isn't why he moved; in fact, he says, it's getting hard to find any location in central South Austin where rents aren't virtually prohibitive. Sooner or later, "property values are going to go up, and businesses will move on," he says. "Don't ask me where they're going to go. I'd like to move too but I don't know where I'd go."

Positively First Street

Over on South First Street, where rents are creeping rather than catapulting upward, Alternate Current Artspace owner David Lee Pratt predicts that a veritable crowd of South Congress exiles will soon stumble westward into his neighborhood. "I think South First Street has an incredible future. It's more pedestrian-friendly than South Congress," he says. "South First is also one of the few integrated neighborhoods in Austin -- black people, Hispanics, white people all living side by side in the same block. Hardly any areas in Austin are like that."

Diversity aside, the reason most South Austin business owners say they are proud of their area is its stubborn refusal to succumb to the wholesale chain-store homogenization that doomed districts like the Drag to being little more than outdoor shopping malls. Despite high rents and South Austin's current cache in the local and national press (the New York Times, for example, ventured to South Austin recently for a profile), South Austin retains much of its funky, eclectic feel. The difference now, according to Off the Wall owner Ellen Johnson, is that people from outside South Austin are venturing in, changing the reputation of the area. "Ten or 15 years ago, if you mentioned that you lived in South Austin to someone from North Austin, they thought you lived on another planet somewhere," Johnson recalls. "Now we're the affordable, political, funky little inner-city neighborhood."

The challenge, Johnson and other merchants say, is to preserve the area's homegrown businesses from being overrun by ubiquitous chains like Barnes and Noble and the Gap, which have encroached on local merchants in virtually every other part of town. "My prayer is to keep it the way it is -- to keep Starbucks out, and to keep the Gap out, and to keep the Banana Republic out," says San Jose owner Liz Lambert. "Right now it's local businesses. As long as local businesses can survive, they'll stay here."

Copyright © 2024 Austin Chronicle Corporation. All rights reserved.