Austin Author Ed Ward Revisits Rock’s First Guitar Hero, Michael Bloomfield

“When you heard Mike Bloomfield play, you got the sense this was the real shit"

By Tim Stegall, Fri., Sept. 16, 2016

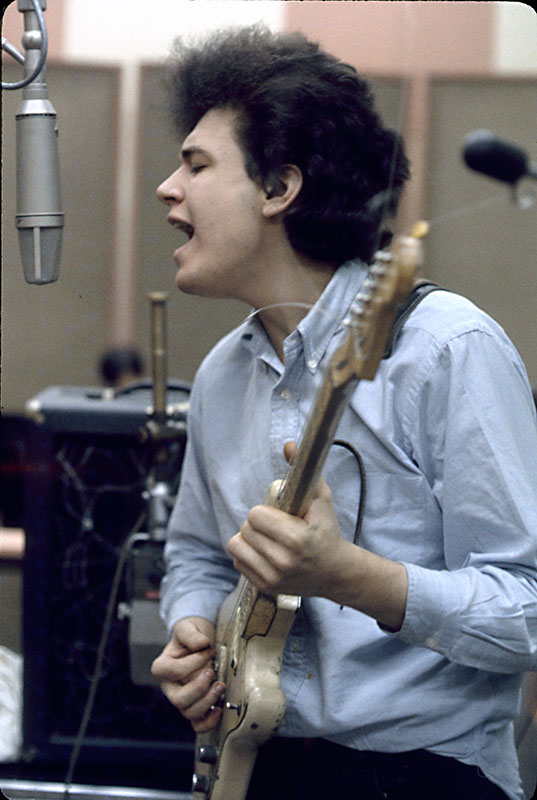

June 16, 1965, New York: Bob Dylan hunkers down in Columbia Studios attempting to apply rock & roll sonics to his beat verse. He's as befuddled as the seasoned session musicians about manifesting the sound in his head. Until a disheveled, frizzy-haired young man walks in from the rain, Fender Telecaster arched atop his shoulder as if it's a rifle.

He plugs in and smiles: "Let's go!"

By August, the session's byproduct, "Like a Rolling Stone," hit No. 2 – kept out of the top slot only by the Beatles' "Help." The trebly blues runs of the song's guitarist, Mike Bloomfield, accompanied Dylan's Newport Folk Festival appearance the following month. Folkies booed.

Others heard the guitar's future.

After the 22-year-old virtuoso finished work on Highway 61 Revisited, he then cut the debut of his day job, Chicago's Paul Butterfield Blues Band, in the wake of Newport. That heady summer of 1965 Bloomfield entered rock & roll history as what Ed Ward, local author of newly revised and expanded biography Michael Bloomfield: The Rise & Fall of an American Guitar Hero (Chicago Review Press, 272 pp., $26.99), calls the genre's "first lead guitar star" – all the events that built his reputation happening within weeks.

"Bloomfield, to people of a certain age, introduced the idea of a lead guitar," surmises Ward. "The Beatles had two guitars, but I never thought of George Harrison as a lead guitarist because it wasn't a jazz-modeled combo the way all blues bands are."

"Bloomfield is the guy who drives onto the block with a jalopy and wins everyone's pink slips," assesses local native Charlie Sexton, Dylan's current lead guitarist. "He had a perfect empathy with Bob, because they were reading the same books and writers, listening to the same records, drawing from the same influences. Bloomfield took it to a more elevated level instrumentally."

"When you heard Mike Bloomfield play," choruses Gary Floyd, mouthpiece for trailblazing Austin punks the Dicks and one of those "people of a certain age," "you got the sense this was the real shit. Everything else came off phony."

"He could just flat-out play," Dylan told Texan Douglas Brinkley in a May 2009 Rolling Stone piece. "He had so much soul. And he knew all the styles, and he could play them so incredibly well. He was an expert player and a real prodigy, too ....

"I think he'd still be around if he stayed with me, actually."

Scion of a Windy City kitchen supplies dynasty, Bloomfield Industries, Michael Bernard Bloomfield wasn't the first child of his era to discover his destiny via the family maid. Falling in with other young, white, Chicago blues enthusiasts in South Side clubs while learning firsthand from masters like Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf, Bloomfield's instrumental voice developed into an overdriven shriek, applying Waters' vicious vibrato to B.B. King's singing single notes. Given full flight with the Butterfield Blues Band, his extended soloing on the group's second LP, 1966's East-West, became a master class for psychedelic bands.

Clashing increasingly with Butterfield, Bloomfield broke off to start "an American music band" in San Francisco. Eventually settling into a soul revue by dint of drummer/co-vocalist Buddy Miles' forceful personality, the Electric Flag proved capable of a formidable live voltage that translated only rarely across two studio documents. Bloomfield's struggles with insomnia and heroin addiction short-circuited Electric Flag tenure – as it would any future ventures.

Bloomfield eventually reunited with Dylan one last time. In November 1980, at S.F.'s Warfield theatre, many in the audience were left wondering about the unkempt schlub in torn jeans and bedroom slippers playing searing lead on "Like a Rolling Stone." And that was after the bandleader's expansive introduction.

Not six months later, Feb. 15, 1981, his body was found nearby in a 1971 Mercury Marquis. Death ruled as cocaine and methamphetamine poisoning, John Doe No. 15 was eventually identified by ex-wife Susan Buehler as Michael Bloomfield, rock's first guitar hero, 37. The lethal cocktail was not known to be favored in the guitarist's chosen pharmacopia.

"Michael was already being forgotten by then," shrugs Ward.

The writer's Bloomfield bio has endured a life as troubled as its subject's. A music journalism pioneer via Sixties/Seventies work in groundbreaking periodicals Broadside, Crawdaddy, and Rolling Stone, he'd interviewed Bloomfield for an unpublished feature as Creem magazine's West Coast editor. While the Austin American-Statesman's music editor, he was contacted by sometime-manager Toby Byron to write a quickie bio shortly after Bloomfield's death.

Typical to the music industry, the first edition of American Guitar Hero was rendered an instant collector's item when the publisher went out of business a week after the book's 1983 release. It soon fetched hundreds of dollars on the used book market from Dylanologists due to a wealth of session information in the pre-internet era. As Ward moved through on-and-off Austin Chronicle stints, NPR Fresh Air spots, and two decades in Berlin before returning to Austin several years ago, he begged Byron to reprint the book.

Those supplications proved to no avail until roughly the time Ward inked a deal for his forthcoming multi-volume The History of Rock & Roll, one of this year's short-list music reads at November's Texas Book Festival.

"Toby got ahold of me and wanted to do the Bloomfield book as an e-book," grouses Ward. "I thought that was a pretty dumb idea, because as far as nonfiction is concerned, e-books don't sell."

Once Chicago Review Press got involved, American Guitar Hero became a print volume again, newly expanded and revised with interviews and new material from uncredited writer Edd Hurt, featuring Jann Wenner's 1968 Rolling Stone interview with Bloomfield, and an exhaustive discography/sessionography. Already in a second printing, consider it a definitive document whatever the provenance.

"How to be co-equal with everyone in the group," replies Ward of Bloomfield's legacy. "Not being a bunch of soloists bumping into each other. Once you learn that, the next thing is to learn how to be a soloist – when it's time to start and when it's time to shut up. I think paying attention to the Paul Butterfield Band's albums and some of Michael's other work will give you clues to that."

"Sometimes," chuckles Charlie Sexton, "the guy with the spoon can cause more damage than the guy armed with a knife or a fork."

A still visibly awestruck Bob Dylan – in Sweet Blues: A Film About Mike Bloomfield, director Bob Sarles' documentary in Columbia/Legacy's 2014 box set Michael Bloomfield: From His Head to His Heart to His Hands – proves perhaps the most effusive on the subject.

"He was just the best guitar player I'd ever heard."

Three Key Bloomfield Moments

"Maggie's Farm"

Bob Dylan, The Bootleg Series, Vol. 7: No Direction Home – The Soundtrack (2005)Recorded at the infamous Dylan-goes-electric Newport Folk Festival appearance, July 25, 1965, Butterfield Band drummer Sam Lay pushes the tempo to hardcore speed as Bloomfield's Telecaster mortally wounds Elmore James' "Rollin' and Tumblin'" riff, then stabs Pete Seeger's eardrums with switchblade blues runs. Those don't sound like boos at the end.

"East-West"

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, East-West (1966)Thirteen minutes of proto-acid rock, featuring samba rhythms and Bloomfield's dynamic exploration of Indian and Latin scales. It schooled San Francisco's lysergic scene in electric guitars, igniting Carlos Santana's career in the process.

"Tombstone Blues"

Bob Dylan, Highway 61 Revisited (1965)The boss directed Bloomfield to not play "any of that B.B. King shit" prior to tracking "Like a Rolling Stone," but that didn't dissuade the six-stringer from unleashing garage-punk slash on this track Al Kooper called "the most scathing raw lead guitar ... since Link Wray."