A Market of Multitudes

Welcome to the new indieconomics of the Long Tail

By Doug Freeman, Fri., Feb. 1, 2008

Ex·po·sured (as defined by White Denim): (ĭek-spō'zhərd) verb. "Performing for the mere possibility of future gain or additional opportunities for exposure."

White Denim is freezing their collective ass off. The thermometer outside reads minus 1 and doesn't even register the ungodly windchill. Wisconsin in the middle of winter is the last place three Austin boys want to be, but for a band barely more than a year old, a stint opening for the Walkmen and doing radio shows across the Midwest can't be passed up. In fact, the band has coined a term for it.

"Everything's a little more 'exposure,'" laughs Denim drummer Josh Block by phone from Milwaukee. "Especially right now and the environment we're in, that word always shows up: 'It will be great exposure for you.'"

After ransacking Red River last year in a blog-buzzed fury, the raucous trio has been well "exposured." Now, as the group prepares their debut LP for release in early March, White Denim is suddenly being forced to navigate the open tundra of the new music marketplace, an economy still chipping at the ice of a technological blizzard.

With CD and major labels in a deep freeze, alternative business models for the industry are beginning to take shape in the drift. Artists are discovering new avenues of support, and bands like White Denim are at the forefront of innovative approaches that are redefining the music business.

Last fall, the band licensed four songs to RCRD LBL, an ad-supported online label that offers free downloads on their site (www.rcrdlbl.com). In addition to paying artists for their material, RCRD LBL in turn works to license the songs to other companies. Like the most promising new business strategies, RCRD LBL's approach combines elements of what has proven successful in the digital marketplace: free downloads, ad-supported revenue for artists, and the possibility of further exposure and revenue through licensing to media sources like television, film, and video games.

"The selling point for us was that it's free-released," acknowledges Block. "If they were charging [fans] for [the songs], we definitely would have thought twice. I can see a lot of people moving in that direction – maybe not that exact model, but that direction. It's pretty obvious with corporate involvement getting bigger these days and being in the scene. I don't know if it's good or bad, but anything that supports music, I think, is good when it comes down to it."

Even more indicative of the new musical landscape is the effort behind White Denim's yet-to-be-titled album. Transmission Entertainment, a local booking and events venture launched last summer, is providing financial backing for the band, helping them buy a touring van and covering recording costs.

"The idea is to use our existing resources to help out in whatever way we can," explains Transmission partner and Mohawk owner James Moody via e-mail. "We believe that White Denim is better than stolen cheesecake, so we put our money where our mouth is. It was never in the 'business plan' for Transmission to take on bands as their own, and that's probably why we only work with one. We are not a record label, nor do we plan to be. This is just what happens when you give music nerds like us the keys to a business."

"It's pretty much a community thing," offers Block. "They're going to be sitting there with us brainstorming about what we can actually do and what's possible. There are no actual defined roles for anyone involved, but just kind of what needs to be done and who has the ability to do it, whether it's us as individuals or a band or someone individually within Transmission. They can be honest about what they can and can't do, and we can be honest about what we can and can't do."

White Denim's arrangement with Transmission mirrors the increasingly blurred relationships and roles within the new unstructured musical economy. As traditional frameworks erode, diverse structures are being erected from the rubble. The keys to the kingdom have passed from major labels to the fans themselves, who are supporting artists directly through downloads and live shows. Being exposured is no longer about playing in front of the right label rep but rather about getting your music to the widest possible audience in a world where a half-million people Googling "song in Old Navy commercial" is more powerful than regular radio rotation.

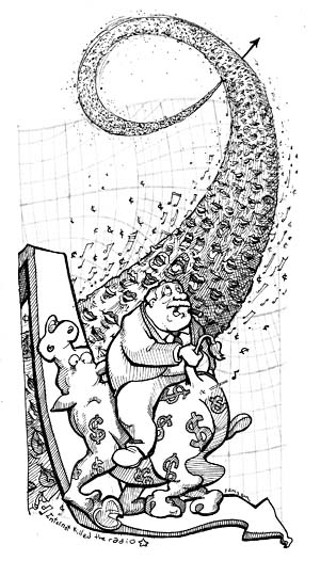

Welcome to the new indieconomics of the Long Tail.

Dark-Sided Computer Mouth

In his 2006 book, The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More, Chris Anderson, editor-in-chief of Wired magazine, outlines the emerging virtual economy. Citing sales results from online companies such as Amazon, iTunes, and Netflix, Anderson discovered that given unlimited storage capacity, the profit scale is nearly turned on its head. Whereas the industry was previously supported by the overwhelming sale of only a few hit CDs, the accrued profit of a large volume of limited-sale items is now more lucrative than high-profile blockbusters.

"Where the economics of traditional retail ran out of steam, the economics of online retail kept going," writes Anderson. "The onesies and twosies were still only selling in small numbers, but there were so, so many of them that in aggregate they added up to big business."

Traditional music economics is still characterized by the Pareto principle, or the 80/20 rule, which recognizes that 80% of sales comes from only 20% of products. In other words, companies from Wal-Mart to Waterloo Records are supported by large volume sales of only a few items. This is the hit-driven economy that has dominated the record industry since the beginning, allowing labels to pay artists ridiculous sums on speculation, only to drop them after one or two "moderately" selling albums.

Physical retailers can support only limited product, so high-selling items continue to stock shelves. Likewise, consumers have long had few available choices, the marketplace driven by a top-down strategy; labels flood the bottlenecked outlets of radio and retail dictating what the public hears and can purchase.

Long Tail economics, however, finds success where traditional industry registered failure. In the digital economy, lower volume sales of a large number of items rivals the higher numbers sale of only a few hits. Adding to the profit share of virtual retailers is the fact that the Long Tail extends almost indefinitely. Given a global marketplace and easy access, every item will find a buyer, and more frequently than anyone anticipated.

As Anderson explains, "That mass of niches has always existed, but as the cost of reaching it falls – consumers finding niche products and niche products finding consumers – it's suddenly becoming a cultural and economic force to be reckoned with."

The new economy doesn't destroy the viability of hits, but it does inevitably diminish their returns as fans are able to find music that better suits their individual tastes. It allows for true democratization of the industry with discretion seized by the public, evidenced in the current cultural influence of small-scale indie bands. For every newly sprung White Denim along Red River, there's a teenage hipster-in-waiting searching for that band's music.

"For a generation of customers used to doing their buying research via search engine, a company's brand is not what the company says it is, but what Google says it is," concludes Anderson. "The new tastemakers are us."

The Long Tail applies to nearly all aspects of our contemporary lives, from personal photos (Flickr) to politics (Ron Paul). It's not simply an economic theory but rather the characterization of a culture of abundance as opposed to one of scarcity. With more choice and easier access, consumers find material that's most relevant to them individually.

"There's still demand for big cultural buckets, but they're no longer the only market," proffers Anderson. "The hits now compete with an infinite number of niche markets, of any size. And consumers are increasingly favoring the one with the most choice. The era of one-size-fits-all is ending, and in its place is something new, a market of multitudes."

Viral Video Killed the Radio Star

Rock & roll was born of a hit-driven, superstar system. Labels manufactured as many formulaic acts and Brill Building singles as could flood the limited channels of exposure. When rare, public-driven revolts of taste occurred – Elvis, the Beatles, Nirvana – the music industry jumped aboard the proverbial bandwagon and continued undaunted.

The model has held for the past half-century, and for all its egregious exploitation of artists and the public, it's still difficult to imagine popular music and the recording industry developing without the centralized control of major label monopolies. Yet like any concentrated power structure, whether governmental or economic, its influence was maintained through scarcity and dictating demand.

The shortsightedness of major labels today lies in their belief that the new business model for music will emerge as a similarly monolithic system that has always dominated the industry. Though some models, like Live Nation's 360 deals – where label, promoter, and management are all one – will take precedent in the new economic landscape, the "market of multitudes" demands more diverse, unique approaches. Radiohead may be able to successfully self-release albums online, but few acts are capable of such digital success and are still at the mercy of an established infrastructure for physical distribution. Labels, however, aren't eager to embrace that diminished business role.

Though the new indieconomics levels the playing field for artists somewhat, it doesn't translate to acts suddenly being capable of reaching unmitigated success. If anything, the saturation of music competing for limited attention spans requires artists to work harder to connect with their potential fans. The rock-star fantasy of big-label money fueling nights passed with hookers and an eightball is more distant than ever.

For the new musical economy, this means both artists and fans must negotiate a vast frontier to connect. The market is suddenly global, and as fans find niche channels that cater to their interests through online blogs, forums, and aggregators, artists can use those outlets to expand their base of exposure. With digital music stores and software such as Snocap or the locally developed IndieKazoo, which allow acts to sell downloads directly from their websites and MySpace pages, musicians can make money from the most distant markets with virtually no overhead.

The key for artists is taking advantage of every possible outlet of exposure. Labels can still provide invaluable business experience, but their usefulness is slowly shifting toward management and distribution capabilities. Artists must, in one way or another, account for their own careers. Yes, it's a job, but the tools are available, and the possibilities are wide open.

Let's Talk About It

"We're set up to where we don't have to do a label thing," offers Thomas Turner, the beat and business mastermind of Austin's Ghostland Observatory, which releases its third album, Robotique Majestique, on the drummer's Trashy Moped imprint Feb. 29. "We have a good distribution deal that we just landed, and I just hired a private marketing firm to handle a lot of the communications. So I've basically hired an infrastructure to help me run the label the same way a major label would. We're pretty much set up to do just about anything that a major label would provide for a newly signed act."

Ghostland's DIY success may be an anomaly, but it reflects the trend. With artists beginning to consider labels not as encompassing entities but simply as another cog in the patchwork business wheels they construct, both major and indie imprints have become an avenue of calculated recourse rather than necessity. Artist conglomerates like Austin's Autobus Records ("Collective Wisdom," May 11, 2007) or financial backing from companies like Transmission can easily supplant labels' traditional roles.

"We're not seeking out labels, and what labels have talked to us really aren't offering anything we can't do for ourselves here in the States, at the moment as least," says White Denim's Block. "We've been talking to labels in the UK, though, because that's a territory we don't have down already. We're looking at labels as experienced business guys who already know the landscape, and Europe is one that we're definitely not familiar with."

Transmission's support of White Denim isn't without local precedent, either. The event agency C3 Presents, responsible for the Austin City Limits Music Festival and Lollapalooza, as well as booking Stubb's and Emo's, also manages a small roster of artists. Among their clients is local pop quintet What Made Milwaukee Famous, which finally sees the release of a sophomore effort, What Doesn't Kill Us, in March through indie imprint Barsuk.

The Long Tail of indieconomics has created a new measure of success within the industry, one that curbs traditional rock & roll iconization and excess into a more realistic standard but also one that's much more accessible for both artists and fans.

"With [the music industry] going downhill, bands like us get heard a lot easier, a lot more now than we would have when everyone's ambitions was to get on a major," says Block. "But still, if you're not 18 and you don't have your parents' house to go back to, you need a little help. That's where I see community-based businesses really coming into play, people like Transmission who take an interest.

"It's not the wisest investment, you know, so they've got to be doing it for a different reason," he laughs. "It's pretty obvious these days that there are better things to put your money into. The only reason people would help out a band is because they like them."