The San Francisco Sound

The Music Was the Message

By Louis Black, Fri., Dec. 7, 2007

I

The first music piece I ever wrote was on the then-current San Francisco Sound for my high school newspaper. Racking my brain, listening to records as well as reading everything available (which wasn't much, mostly Crawdaddy! and random record reviews), I was trying to figure out how to define that sound. Finally I suggested that it had a lot to do with the bands' efforts to re-create their live sound in the studio. Even then this was way off-base.

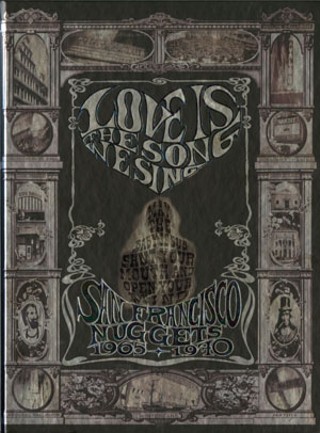

As music critic emeritus Ben Fong-Torres writes in one of the introductory essays to Rhino Records' 4-CD Love Is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets 1965-1970, "I've never understood that tag [San Francisco Sound]. Maybe it's just me, but I find it difficult to listen to Big Brother & The Holding Company's 'Down On Me,' Jefferson Airplane's 'It's No Secret,' and Country Joe & The Fish's 'Section 43' and make obvious musical connections between the Big Brother's raw blues, the Airplane's folk-rock, and the Fish's acid visions."

It took years of writing before I was comfortable with the idea that specific cultural movements such as New York punk, the French New Wave, progressive country, Sugar Hill rap, New Wave, young German cinema, and so on weren't really defined stylistically. Instead, they had a lot more to do with the emergence of an array of creative talents at the same time, artists innovative in their rethinking of a medium as they rejected its accepted aesthetic standards.

The bands of the New York punk/New Wave scene share the Velvet Underground, New York Dolls, and Stooges as common heritage, while all also acknowledged the importance of the Ramones. What acts like Television, Patti Smith, Richard Hell & the Voidoids, Talking Heads, the Dead Boys, Fleshtones, Blondie, Suicide, and Mink DeVille really share, however, is that they emerged at the same time, most coming out of CBGB.

II

Labeling the music that emerged from the Bay Area between 1965 and 1968/69 as being part of an interconnected scene is nevertheless accurate. The Jefferson Airplane and Moby Grape (along with L.A.'s Byrds) were the first bands with which I really fell in love. This isn't to overlook my affection for the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother & the Holding Company, and Sopwith Camel, among others, but listening to the Airplane and Grape took me to places I'd never been. The music was critical, but the San Francisco mystique and lifestyle were part of the package.

III

There was so much happening musically in the latter half of the Sixties, as well as so much music from the past to discover, that chronology, musicians, musical heritage, and songs all run together in my memory with precious few specifics standing out. Acts weren't really defined in terms of regional scenes at the time, but maybe because Haight-Ashbury evoked so much more than an intersection – a whole hippie lifestyle, rather – the San Francisco scene was always thought of as a geographic entity.

Bands were heard of long before they were actually heard. Pictures of the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane in Time and Newsweek seemed impossibly exotic. Those that have come of age in these times of the Internet, iTunes, MTV, and the prevalence of rock music in all media including TV and movies probably can't really grasp the pony-express way news spread then. It was frustrating, but it also allowed for a mysterious fog to envelop this music. Fitting, given San Francisco's weather.

In January 1967, the massive Human Be-In was held at Golden Gate Park. Called "a Gathering of the Tribes" – could there be a more potent image? – Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsburg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder, Dick Gregory, Lenore Kandel (a poet known for her sexually graphic work), and playwright Michael McClure (The Beard) all read, chanted, and spoke. The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother & the Holding Company, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and the Sir Douglas Quintet played. The news showed everyone smoking pot, while the word was that LSD guru Owsley Stanley wandered the crowd, a hippie Johnny Appleseed planting his wares in the consciousness of all.

Is it any wonder that the Summer of Love followed? Perhaps even less surprising is that before the year was over, in October 1967, a mock funeral was held in the Haight mourning "the Death of the Hippie." The following month, the first issue of the then-biweekly Rolling Stone appeared with John Lennon on the cover.

Clothing, long hair, pot, rock posters, LSD, underground papers and comics: The hippie and freak lifestyles were all aspects of what was happening. What an alluring package, combining music, lifestyle, renegade consciousness, and politics.

The music was the message. The handfuls of pictures, random stories, and oral legends all led to it. The bands, fine on records, were even better when finally heard live.

Still, the music itself also came in frustratingly slow-moving concentric circles. Surrealistic Pillow was released February 1967, spawning two radio hits in "Somebody to Love" and "White Rabbit." Although the Airplane's first album, The Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, was released September 1966, it had done so under our radar. The Grateful Dead was released in February 1967, Moby Grape followed in June, and the Airplane's wonderfully strange and overindulgent After Bathing at Baxter's in December. In May 1968, Quicksilver Messenger Service was released, with the first really defining Grateful Dead album, Anthem of the Sun, coming that August.

The Be-In was followed in June 1967 by the Monterey International Pop Festival, the generation's defining music event. Everyone heard the Monterey stories, about Otis Redding stealing the show, Janis Joplin coming into her own, and Jimi Hendrix blowing away all with his otherworldly genius. Consider that more than half of the albums listed above came out after Monterey (five months before Rolling Stone debuted). The myth preceded the eagerly anticipated music by such stretches of time that myth and music lost defining boundaries becoming and being received as one.

IV

The mystery, mystique, and exotic were all crucial to the San Francisco scene, but the center was the music.

The beautiful harmonic power of Marty Balin's and Grace Slick's voices blending together on Surrealistic Pillow and the full encyclopedic but cohesive playing on Moby Grape blew the top of my head off then and can still do so now. Early Dead, Big Brother, Mother Earth, Country Joe & the Fish, and Quicksilver Messenger Service all were engaging and are still more than simply entertaining. Unfortunately, Love Is the Song We Sing is too much a scholarly collection, designed more as a historical document to convey the time, scene, and music than a musically coherent collection.

In another of the set's opening essays, Gene Sculatti celebrates this very inclusiveness. Rather than Love being "Frisco-centric" or just featuring the hits, Sculatti writes, "On the basis of what's heard here, you'd have to say that Northern California in the mid-1960s constituted one of the country's most vibrant regional scenes." Unfortunately I don't have to say that, because instead I find the ambition to convey that is this anthology's greatest failure. One entire CD of the four is devoted to mostly unknown Northern California bands of the period. Being a student of music history, I'm interested in listening to this, but in its attempt to convey the fullness of the San Francisco scene, the disc is an academic distraction. Ignorance be my guide, but I just can't work up much interest in the Front Line, the Mourning Reign, the Immediate Family, Public Nuisance, the Savage Resurrection, and so on.

The packaging is beautiful, the essays excellent, the annotations for each cut knowledgeable and fascinating, all of it accompanied by stunningly reproduced photographs. Even with all that, however, how many pictures of young men with long hair in bands never heard of can one find entertaining?

There aren't enough unheard goodies to excite anyone already enamored and/or familiar with the scene. A couple of EP versions of songs, some original single edits, and a few live versions are about it, with not one being revelatory or enlightening. All told, there are considerably less than a dozen rarities out of the more than 75 tracks.

One of the collection's strengths is rarely heard work by bands that heavily influenced the scene, including the Charlatans, Mojo Men, Beau Brummels, and the Great Society, as well as cuts by bands that evolved into major players; the Warlocks became the Grateful Dead; Dino Valenti joined Quicksilver. But way too many of the selections are from readily available albums. Groups like Salvation, Ace of Cups, the Loading Zone, Fifty Foot Hose, Kak, Sons of Champlin, and Mad River are definitely of some interest. A lot more live recordings, jams, different bands' members playing together, or really obscure releases by the Dead, Airplane, Grape, Quicksilver, Country Joe, Big Brother, and the like would have gone a long way toward redeeming this collection.

Which raises the question as to who the target audience for this collection is. There are way too many cuts by obscure bands (including almost the entire second disc) to be of interest to the novice. The lack of unusual/unknown cuts along with the too-historically oriented organization of the tracks undermines Love for anyone familiar with the music. Only those music fans who combine obsession with listening pleasure, valuing the obscure and unknown as much as the music, will be fully delighted here.

V

What makes Love Is the Song We Sing especially frustrating is that at the end of the day and 40 years, I've come to understand that there was very much a San Francisco Sound. The musicians joining together to form those bands didn't share a single common cultural background but, rather, came out of folk, blues, jug-band music, country, bluegrass, and rock. They abandoned all these styles, then brought them forward, spicing it all up with psychedelics and straining the ideas through the times until it was all one unbelievably rich and potent brew.

The San Francisco Sound was the combination of so much music that came before, uniquely combined into many different sounds yet all played with enthusiasm, skill, knowledge, love, and an impossibly optimistic energy.

Instead of the driving 3-D explosive pop-up-book anthology that would suit the music and do it justice, what's here is a work of history. Interesting, sometimes fascinating, but never really exciting, rather than blow the top of your head off, Love Is the Song We Sing inspires you to put your glasses on and take notes.