Dead Man Blues

Near-Forgotten Delta Icon Charley Patton and the Austin Label That Revived His Music

By Clay Smith, Fri., Oct. 26, 2001

The Jinx

The blues is you're 43 and dead. The blues is when you live in the Mississippi Delta, it's 1929, your Grandpapa is white, and you're black. When you go to the station and the train has left, that is the blues. It's when you're so good-looking a man would cut your throat because he thinks you were singing to his wife (and maybe you were). But you survive.

Women = the blues. Having seven of your 11 siblings die in infancy or childhood could prompt you to sing the blues. The blues is trying to get right with God but picking up your guitar one more time. If someone wakes up in the morning with the jinx all around their bed, a symptom of the blues is that they may turn their face to the wall without a word to say. When Charley Patton got the jinx -- quite often, judging from the frequency with which he sings about omens -- he realized there was

No use a-hollerin', no use screamin' and cryin'

No use-a her hollerin', no use a-screamin' an' cryin'.

Patton never made a pact with Satan at the Crossroads, like Robert Johnson did. Although he was vastly popular throughout the Delta, and was the most widely recorded of the first generation of Mississippi blues singers, Patton was left behind when artists like Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters began to acquire young white fans in the Sixties and old blues recordings began to sell.

The people who took a cue from him -- Johnson, Skip James, "Son" House, Joe Williams, Bukka White, Willie Brown, Roebuck "Pops" Staples -- experienced a revival, but Patton has remained a cipher, interpreted at one time as a sloppy drunk who beat his wives (scholars say there were eight of them). He was also labeled a merely casual entertainer who garbled through his verses and sometimes made them up on the spot.

"Charley, he could start singing of the shoe there and wind up singing about that banana," Son House once said.

When he wrote about Patton in 1970, the late folk troubadour and noted guitar composer John Fahey pointed to the "disconnection, incoherence, and apparent irrationality" of Patton's songs. "Various unrelated portions of the universe are described at random," he wrote with scholarly dismay. Patton's recordings sound muted and unfiltered to the modern ear, and leave the impression that he happened to be singing on the street when a roving troupe of recording engineers managed to trap some of the sound.

But more forbidding than technological imperfection is Patton's particular style. He doesn't sing, he growls. It is often hard to discern what his songs are about because his verses consist of words that, once he gets ahold of them, hop over one another, bleed messily into one another, and are sometimes just discarded altogether. Some of his songs seem like one long exhalation whose particulars can't be parsed.

His diction is bloated, so much so that it must be purposefully like that. As music columnist Tom Piazza says in an article about Patton in the Oxford American's recent music issue, the word "door" comes out as "duwowwwwwahhhh." Listening to him for the first time is to be assaulted by something that doesn't sound quite right. If you wonder whether it's English, you're on the right track.

But Patton isn't necessarily trying to obfuscate; his music is frightening because it's hard to penetrate. Once it grabs you, though, it lets you in on a subtle, witty, and sometimes funny secret: Charley Patton is inspired by the things he has no control over. These include: death ("Prayer of Death"), being unable to escape when you badly need to ("Circle Round the Moon"), mean black cats that must be killed ("Mean Black Cat Blues"), white people ("Revenue Man Blues"), omens ("Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues"), and more death ("I Know My Time Ain't Long").

Fahey writes that "in spite of the many compliments people and relatives and blues colleagues paid him -- Patton's opinion of this world is that it's a big gyp, a waste of time, a vale of tears and he just can't wait to get to the next one."

Exactly why Patton was so popular -- famous enough to foster at least one imposter -- is a mystery at least partially solved by several writers contributing to Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton, a prodigious, monumental 7-CD box set put out by Austin's Revenant Records. Housed in a hardback book styled to look like an album for storing 78s, Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues is exhaustive.

Five CDs contain the material from all of Patton's recording sessions and the songs on which he may have accompanied other performers. One CD has 24 tracks from various artists he influenced, while another one is full of interviews with people who knew him. Three essays and a reprint of Fahey's 1970 book on Patton reveal all that is known about him, and a "sticker set" of record labels gives you something fun to do when you're feeling a little exhausted by the set's biblical heft.

There are also complete reproductions of the ads that heralded Patton's songs. When Patton recorded his epic lament "High Water Everywhere," about the massive April 1927 flood in Mississippi that he witnessed, his record company bragged:

Everyone who has heard this record says that "HIGH WATER EVERYWHERE" is Charley Patton's best and you know that means it has to be mighty good because he has made some knockouts. You're in for a real treat when you hear this record at your dealer or send us the coupon.

"In the recording studio, the blues, like everything else, was ad captandam vulgus, calculated to take the fancy of the marketplace," Nick Tosches writes in Where Dead Voices Gather, his recently published meditation on the life of yodeling blackface performer Emmett Miller.

The music, of course, solves the remaining mystery of Patton's popularity. "Uncle Charley could take the guitar and make it talk," his niece, Bessie Turner, recalled. One song, which Patton calls "A Spoonful Blues," is believed to have originated in the 19th century, when a spoonful of cocaine was something a relatively widespread percentage of the population could have experienced. Patton recorded it in June 1929, his first session (he died five years later from a heart condition).

The only time the word "spoonful" appears is when Patton says "I'm about to go to jail about this spoonful" before he begins playing. Other artists sing openly about the spoonful, but leaving it out, as when Patton sings

Yes, I'm goin' crazy every day of my life 'bout a...

It's all I want in this creation is a...

I go home wanna fight 'bout a...

drapes a lingering mystery over the song that is articulated only by his jangly steel guitar. What sound like the voices of different people -- men, women, and children -- provide spoken asides full of implications about addiction and violence. The box contains another essay from Fahey in which, among other insights, he repents for his misinterpretations in 1970 and points out that it sounds as if there might be 20 to 30 people joining Patton in the song when it's only Patton himself. In Charley Patton's imagination, you can find not only the atavistic rumblings of a blossoming art form but adumbrations of blues yet to come.

Patton was also a consummate professional who wore a suit every day and, according to Reverend Booker Miller, never showed up late for a performance. "Charley Patton, Willie Brown, and Son House, the triumvirate of 'primitive' Delta blues masters, were, in the black parlance of the day, gay cats," Tosches writes in Where Dead Voices Gather.

Patton sprinkled his songs with the names of places that would have been familiar to his audiences, was unafraid of pointing his finger at white people, and accorded events in the Delta and his own life a newsworthy status in his music. He put up with, but bristled under, categories that made it possible for a rifle-toting white man to halt a black dance where Patton was performing in Blaine so that Patton would come and play at his party on top of a bridge.

"And Uncle Charley sat on that bridge and played for them white folks until about five o'clock the next morning," his niece said.

"The idea of a white man in the Delta hijacking Charley Patton from a black dance to play for whites is enough to boggle the mind," Patton biographer David Evans observes in "Charley Patton: The Conscience of the Delta," one of the essays in Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues.

"One wonders if Charley or any of the whites attached any significance to all this," Evans writes. "Were the whites drawing Charley into their world for a night? Or was Charley drawing the whites into some inscrutable world that fascinated them but which they didn't really understand?"

Out of Time

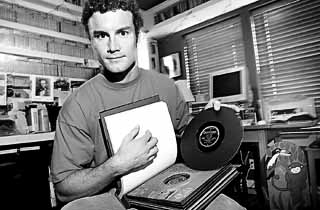

In high school, Dean Blackwood was one of the people who seemed to have it figured out. He was a jock but he had a spiky hair phase (the punk aesthetic did not fully infiltrate Arlington until 1984, when he was a freshman).

Blackwood was conversant enough with the freaks and the ropers that he was able to elude dislike from both. Earlier, in the seventh grade, his friends wanted to go to an Iron Maiden concert -- "I was as big on Iron Maiden as anybody," he recalls -- but he opted for Stevie Nicks. The day after, he wore the shirt he bought at the concert, "and people were like, 'What are you? Some kind of pussy?'

"Arlington wasn't a real hotbed of the arts," Blackwood told the Chronicle recently when meeting to discuss his record label, Revenant Records. "We got most of our cultural information 15th-hand."

The account of how Blackwood made up for lost time by running one of the nation's most defiantly eclectic and almost indescribably selective small record labels began, as these kinds of stories always do, with a bit of luck. In 1994, Blackwood was attending Harvard Law School and in his spare, miscreant time, putting out a limited series of 78s on a label he called "Perfect."

"I was trying to do music that had a really organic connection with the format," he says, "something that wouldn't sound contrived or scratchy or something like that." He would drop them in a bin of 78s at, say, a flea market or used record stores. What he recorded on the 78s "was not supposed to sound old-timey anymore, it was supposed to sound sort of out of time," like Charlie Feathers or Sun City Girls or Junior Kimbrough.

The idea was that some unwitting 78 searcher would purchase one of his records, take it home, play it, and never be entirely certain whether the music was new, old, retro-hip, or brand-new hip -- a cultural gag with some contemplative bite to it. During this time, Blackwood read an article in Spin that updated readers on the whereabouts of Fahey, whose timeless, intricate guitar compositions Blackwood was a fan of.

People who knew Fahey, who passed away this past February, respond to the mention of his name by shaking their head in a wistful and rueful way.

"When I first met him, I had never heard him speak before," Blackwood remembers, "and I thought, 'I think this guy's had a stroke, it's just been undiagnosed.' It was, 'Hi Dean, how are you?'" Blackwood mimics in a foggy, protacted manner -- like Bullwinkle's voice one setting too slow on a record player. "I think what it was was that he had a true artist mentality. If it wasn't immediately serving his needs or didn't involve something he was focused on right at that moment, then it was a distraction ... and that included ordinary things like upkeep around his room, keeping his money actually in a pocket."

By 1996, Blackwood was working at a law firm in Nashville. Fahey's father had died, leaving him $50,000, which Fahey gave to Blackwood to start their record label. Fahey was responsible for producing the big picture for the label. "The deal was that he would occasionally flash brilliantly, and I would pay the bills and make the arrangements and get things done," says Blackwood.

They decided that the music they liked -- the only music they liked -- had an "undiluted" quality. "It's like looking at the oral equivalent of turbinado sugar," Blackwood says. "It's almost meaty looking, it's very mealy, and you can squish it up in your hands and make something of it. After a while Fahey just started to say (and he was a classic naysayer), 'The thing that ties it all together is just that we like it all.'"

But Revenant doesn't seek out musicians merely because they weren't accepted by the marketplace; they like unadulterated music by artists who wrestled with the need to make a living. "The music doesn't seem slickified for commercial taste in any way, even though that was the intent -- to sell records," Blackwood says.

But after Fahey paid off his bills, bought some digital recording equipment, and squandered some of it, $20,000 had been spent. $30,000 is enough to start a record label, though, and in January 1997, Revenant released its first CD, a collection of works by British guitarist Derek Bailey (see discography).

Blues That Just Won't Quit

Several weeks ago, a British music journalist asked Blackwood, who now works as a lawyer at Dell, why Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues is being released now. After telling him that the two years it took to produce the set are up, Blackwood turned the question around with a lawyer's exactitude:

Maybe the question is, why do folks seem to be more interested now in such a document than ever before? Seems pretty clear that beginning around 1997, with the re-release by Smithsonian Folkways of the CD version of the original Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music, and culminating in the recent staggering multi-million selling success of the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack, we are in a different age of music listeners. May have something to do with a backlash against the 90s insincerity/ironic distance formula, the logical terminus/artistic nadir of the "post-modernist" take on the arts. (The so-called "cocktail nation" would be a prime offender.) People seem to have grown very tired of being winked at by performers who cloak their dubious "statements" in enough irony to largely make them immune to criticism, embrace, or even simple assessment, and, even prior to the latest tragic events, music listeners seem to be seeking something sustaining, something which has a readier ring of timelessness, like they found in earlier eras in the musics of Coltrane, Dylan, and a few others. So, generally, you've got the confluence of the original fans of these musics and fed-up younger folks, I think, feeding into the astonishing current interest in this stuff.

Recently, and particularly since Sept. 11, cultural arbiters have been declaring that irony is no longer earning its keep as an artistic stance, and that it may be time to retire it or to employ it only in a part-time capacity. It's an argument that has a great deal of validity, but to adopt it means running the risk of seeming joyless. Because Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues is such a massive work of scholarship and redemption, it is easy to dismiss it as a stern, grave institution that admits only the previously initiated into its ranks.

The reality is a bit more complicated. This is an exhaustive work of scholarship with a "sticker set" of Patton's original record labels. What are you supposed to do with these stickers, exactly? Be puzzled.

"This is aimed at a population, most of the members of which are so obsessive that they would never actually remove any of the stickers in here because that would be like sacrilege," Blackwood says. "So the joke is, Yeah, you can slap them on all your run-of-the-mill 78's and you can continue to have a full run of Charley Patton records."

An invitation to the release party for Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues announces:

-- Blues That Just Won't Quit --

Get yourself ready for some of the finest recordings you ever heard. The way the famous artist sings and plays is too good to miss. What he can't do with a guitar ain't worth mentioning. It is Revenant's treat and what a treat we are giving you.

This stilted, inauthentic language, which pops up throughout Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues, may be strange and funny, but the impetus for it is deadly serious. There are two camps of people who listen to archival music, Blackwood says: academics, who gravitate toward releases "where the music is always in service of the writing instead of being first and foremost a compelling listening experience." The other camp "just puts it out with only the notion of having the most compelling stuff out there, but then do nothing as far as buttressing that with good scholarly work.

"People want to know about the tradition going on," Blackwood insists. "That's a great thing if it's in service of the music. If it's the other way around, I think you end up with only a bunch of pinheads being interested in it. There's a lot of playful stuff in [Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues], the depth of scholarship is there, but we dispense with the pretense."

Blackwood works on Revenant business every night and weekend, and his wife Laurie manages to help out when she's not working as a nurse or taking care of their two girls. But running Revenant full time is not something he envisions.

"I'd have to think in wholly different terms," he realizes. "It would be less fun, I think." ![]()

Revenant presents its Masked Hoodoo Ball and Release Party celebrating the release of Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton on Saturday, October 27, at 8pm at Thirty Three Degrees, 4017 Guadalupe. Live music by the Bassholes, Tim Kerr & Mike Carroll. Free beer. Costumes encouraged.