Ruling the Roost

The Live Music Capital's Notorious Captain of Industry, Tim O'Connor

By Andy Langer, Fri., June 1, 2001

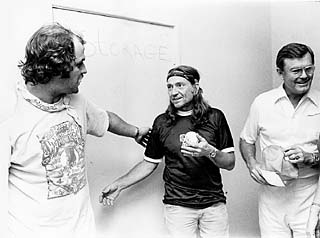

If he hadn't been driving the getaway car, Tim O'Connor might have punched Willie Nelson.

"I was screaming at him," recalls O'Connor, nearly 25 years later. "I wanted a fight."

What O'Connor didn't know at the time was that many shows at Houston's legendary Gilley's dancehall ended with more people onstage than in the crowd. This was one of those nights. Grabbing Nelson's beloved guitar Trigger, pushing the country music icon into a waiting car, and beating a hasty retreat, O'Connor had no idea that the cowboys rushing the stage were merely fans who loved Willie and wanted to show their appreciation. Berating the singer for letting his encore be overrun, O'Connor began yelling.

"Why I am I here? What do you want me to do? What do you want me to be?"

In those days, nobody in Nelson's Family had a title: If you had to ask for one, he didn't need you. If you didn't know what you were doing there, he didn't either. And yet, even after being yelled at by $25-a-day roadie, Nelson answered with typical calm.

"What do I want you to be?" Nelson repeated. "I'll tell you the three things I never want you to be: cold, wet, or hungry."

Three words that changed O'Connor's life.

"Something clicked," says the 56-year-old promoter today. "For the first time in my life I knew I had to put my faith somewhere. I'm not sure if I said it or not, but I knew right then that I was willing to carry this guy's guitar to hell."

Tim O'Connor's association with Willie Nelson has yielded lots of similarly colorful tales over the ensuing decades, but they're a small part of his story. As Austin's most successful concert promoter, O'Connor has earned and lost several fortunes, ridden deals to the edge of bankruptcy, and played chicken with the IRS since his arrival in town during the early Seventies. More to the point, it's been decades since Tim O'Connor carried anybody's guitar and worried about being cold, wet, or hungry.

Whether you know it or not, if you've seen live music in Austin over the past 20 to 25 years, you've likely given money to Tim O'Connor. In the Seventies, he reigned over Castle Creek. In the Eighties, he owned and operated the Austin Opera House, while co-founding Star Tickets and staging hundreds of large-scale festivals and benefits, from No Nukes concerts to Farm Aid. Today, he owns three of the city's most popular venues: La Zona Rosa, the Austin Music Hall, and the Backyard.

"Once upon a time, we were all fighters that ruled our own little neighborhoods," says Threadgill's Eddie Wilson, who once competed with O'Connor at the Armadillo. "Tim ended up ruling the whole roost."

Ruling the roost is an unpopular business, and over the years, O'Connor's reputation has often overshadowed his accomplishments. In the offices of Direct Events, the production company that runs his venues, associates call him "Crazy Ivan," a reference to the brash and unpredictable submarine captain in Hunt For Red October. He's equal parts Tony Soprano and Bill Graham.

"I've probably given plenty of people cause not to like me," admits O'Connor.

He also volunteers that he's probably amassed as many enemies as friends. Employees fear him and competitors loathe him. By his own admission, he's been quick-tempered, cold, and generally disagreeable for much of his career. It doesn't take much asking around for folks to recall the first time he screamed at them, or the first time they witnessed him either stand on his desk to make a point, or clear it with the sweep of an arm.

What few of these people will do, however, is tell these stories on the record. Some still fear him. Others have let bygones be bygones. Then there are those that "respect" him too much to dredge up the past, those content with allowing O'Connor to spin his own story, particularly considering he's on the cusp of retirement and still recuperating from triple-bypass surgery.

More than anything else, the stories told and untold paint the picture of a man who knows how to get what he wants, a notoriously stubborn and tough negotiator who never shied away from staging a charity event or benefit. Yet for all the yelling, he's known real pain of his own: He's lost a testicle to cancer and a daughter to drugs. His closest friends tell the story of a private man who's embraced the "Crazy Ivan" image as a front for less sinister passions: music itself and the belief that few vehicles serve and strengthen a community as well as a properly promoted concert.

While most people don't care who owns the venues they visit, it could be argued that the one non-performer's name every Austin music fan should know is Tim O'Connor. He brought a level of professionalism to local concert promotion previously unseen, not to mention a wealth of shows unlike anything Austin had ever experienced. Now, as his relationship with SFX, the country's largest concert promoter, nears contractual completion, the impact of O'Connor's retirement on the local promotions pool is unknown. Likewise, his exit strategy remains characteristically ambiguous.

"I'm a loner," says O'Connor. "I'm known for being a guy that keeps a lot of things to myself. I may have given up a certain amount of information here or there, but my past is that nobody really knows what I'm up to. I believe it's given me an edge as a competitor and given us a distinct advantage as a company."

The tale of Tim O'Connor starts with a Baby Doe born in Great Bend, Kansas. After roughly 26 months in an adoption facility, he was adopted and given the surname O'Connor. By sixth grade, he was sent to a boy's school in Arkansas for three years. After a short stint at a Jesuit high school, he was again shipped away for discipline: this time to Kemper Military School in Booneville, Missouri. In 1960, after eight months of marching with a weighted backpack and an M-1 rifle, O'Connor and several other cadets broke ranks, literally running away and leading police on a manhunt.

"Obviously, there's already a pattern developing," smiles O'Connor. "I didn't take direction very well."

Apprehended and returned to Wichita, it wasn't long before O'Connor ran away again. Winding up just outside Southern California's Laguna Beach, O'Connor approached a house for sale and asked the family moving out if they'd pay him to help. They did him one better, allowing him to stay in the garage apartment of their new house.

After enrolling in a local high school, he immersed himself in student theatre (he was Conrad in Bye Bye Birdie). There was other drama as well: He'd been caught attempting to steal a WWI cannon from the town post office. (The plan had been to throw it in the high school swimming pool.) That arrest led the state of California to declare him an emancipated juvenile; he could now be tried for adult crimes. After graduation in 1963, he decided to tempt fate and stay in-state, attending Monterey Peninsula Junior College.

"We had a lot of fun, a lot of drinking," says O'Connor, who ran for his freshman class vice-presidency and won. "I didn't have much fear and figured I didn't need to take much guidance from anyone else."

Somewhere along the way, O'Connor started a band in Laguna. He was the Wanderers' cardigan-wearing lead vocalist, and he landed them gigs at area sock hops and talent shows. During the same period, he rented Laguna Beach High's gym for $50 and threw a concert featuring a semi-popular local band. What O'Connor didn't know was they'd since befriended another fledgling band, Buffalo Springfield, and as word of the two bands' association spread, the show sold out on the belief Stephen Stills and company would show up to jam. They did.

"I cleared a few hundred bucks easy," O'Connor says. "It got me thinking."

Unfortunately, before he could think on it harder, a night of drinking in Carmel led to another arrest; police picked up O'Connor and his buddies after neighbors reported having seen them prying at a metal cage in front of the local liquor store. Attempted burglary charges led to 27 days in jail, a trial in Salinas, and six years of probation. After the conviction, O'Connor says state authorities recommended he leave the state and not return.

Kansas State University was the next institution to ask O'Connor not to return. From there, he landed a job in Dallas working at various local bars and hotels. Soon married with a baby, he returned to California, where he eventually wound up laying drainage pipe in the Mojave Desert. Separated from his wife, the couple later returned to Kansas to try and make the marriage work. It didn't, and at 22, he moved to Colorado while his family left for Atlanta.

In Colorado, O'Connor was offered a deal for a restaurant/bar/apartment combo along I-70, in the mountains not far from Winter Park. With income he'll only say was "not legal," O'Connor took ownership of 13 bungalows and a bar he named the Lift. At the time, musicians such as Jimmie Vaughan and Rusty Wier began stopping at the restaurant on their way to Winter Park. Seeing an opportunity, O'Connor began inviting them to play his bar in exchange for free lodging in the bungalows below. The other rooms he rented.

"Anytime someone was more than 90 days behind on rent, I'd go down and take their front door off the hinges and hold it in the office until they'd settle up," O'Connor says. "Winters are fairly cold in Colorado, so it became a strong collection approach."

Although O'Connor did some settling in before utilizing similarly strong-arm tactics in Austin, his arrival was still relatively splashy.

"The town had just gone from zero to 65 clubs in 18 months," says Eddie Wilson of the city's early-Seventies live music boom. Along with Wilson's Armadillo, and the One Night, Soap Creek, Split Rail, and Broken Spoke, there was the Checkered Flag, a fledgling beer joint on Lavaca owned by future Kerrville overseer Rod Kennedy and his partner Allen Damron. When a mutual friend invited him to Austin for what amounted to a consulting gig for the venue, O'Connor signed on as a partner and re-christened the club Castle Creek.

Moving into Michael Martin Murphy's house on 54th across from the DPS and forging fast friendships with musicians like Jerry Jeff Walker and Jimmy Buffet, O'Connor quickly made Castle Creek's bookings competitive. Almost immediately it became the place to not only see roadshows such as John Prine, Jackson Browne, and Bonnie Raitt, but the cream of Austin's burgeoning singer-songwriter scene: Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, Stephen Fromholz, and Delbert McClinton. O'Connor says the business side of concert promotion back then was fast and loose, but not very competitive.

"Clubs might argue over one act, once a year or so," he says. "That's where I learned to present the best show -- show by show. I remember certain nights with Steve Goodman or John Prine where I physically threw people out for talking. On those nights it was a listening room. On others, it was a place for hell raising, hooting and hollering."

That O'Connor quickly became known as the best "operator" in town paid off quickly.

"Willie had long been my songwriting hero," explains O'Connor, "and out of the blue, he just walked in, asked for me, and said, 'Hi. I'm Willie Nelson. I wanna work your joint.'"

Not only did Nelson play Castle Creek, he also offered to take O'Connor on the road.

"Tim and Willie were an odd couple," says Arlyn's Freddy Fletcher, Nelson's nephew. "He was apt to go off, which was a sign of the times, but we were always a little more laid back."

On the road, O'Connor got his hands dirty re-wiring sound systems and handling payouts, but his stint with Nelson was short-lived.

"The first chance he had back in Austin, he fired me," reveals O'Connor. "He called me into his office and said, 'Tim, I just want to let you know I think you did a great job, but I think you're maybe just a little ahead of us. Why don't we wait a little while and maybe we'll catch up with you.'

"I thought I had done well, but what I was really doing was screwing every relationship he'd established in every little town in Texas and Louisiana. Of course, I didn't really go anywhere. I stuck around Willie like bad penny."

Along with working in Nelson's front office and running Castle Creek, O'Connor also found time to open a non-music club, the Squeeze Inn, a bar on 19th Street where the pool tables, jukebox, and beer were all a quarter. Once again, the good times didn't last -- local authorities asked him to leave town.

"There was an incident in front of the Alliance Wagon Yard," states O'Connor. "A stray bullet was fired and went into somebody's leg. It just so happened it was my stray bullet."

Turns out O'Connor had shot a label executive with CBS Records, with whom Nelson had just signed.

"I met Willie in San Antonio to apologize to him," recalls the promoter of his last move before leaving Austin. "I knew I'd screwed up big and made my mea culpas. He let me spill everything out for him and then I asked, 'What do you think?' I'll never forget Willie's answer.

"'I think I'm going to let you negotiate all my contracts with CBS.'"

It may not have cost him his friendship with Nelson, but O'Connor's stray bullet came with a hefty price tag -- having to leave Castle Creek. Then again, once a drifter, always a drifter; this time, O'Connor settled in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and hooked up with a friend from his Colorado days, songwriter Tom Campbell. What started as benefit concerts for local Native Americans grew into something far bigger: star-studded concerts pairing artists with causes. One night they'd be working against nuclear weaponry, the next for prison reform.

If producing five nights at Madison Square Garden wasn't experience enough, O'Connor found himself immersed in a contact sport; By working closely with artists like Bonnie Raitt and Jackson Browne for charitable causes, he was rapidly building a national network of artists, managers, and booking agents.

"I got to know an immense amount of people really well," he says. "It wasn't by design, but it worked out that way."

Unfortunately, O'Connor almost didn't get an opportunity to use his new Rolodex entries. At a benefit in Monterey, O'Connor collapsed onstage. He knew he'd been sick for some time, but blamed it on exhaustion. He wound up in Houston, diagnosed with cancer. It had spread for as long as six months undetected, and surgeons removed not just a testicle, but also portions of his small and large intestines.

"I made it through," nods O'Connor, "but I came out weak."

After recuperating, O'Connor returned to staging benefits and working with Nelson. In 1977, he led a group of almost 200 musicians on a cultural exchange trip to Japan. It was the first O'Connor production to require a 747.

"Can you imagine sending a guy like me over as an ambassador of goodwill?" quips O'Connor.

While at the San Francisco airport, after making it out of Japan without sparking an international incident, O'Connor and Nelson discussed opening a club together. The singer believed he'd stumbled on the perfect property. Not only would the building at 200 Academy provide them with a 56,000 square-foot main building, the two would also be buying 218 apartments in 17 different buildings, stretching from the corner of the Travis Heights neighborhood to South Congress.

"When Willie and I needed to deal with banks, we'd be sure to pull up in front with the bus," explains O'Connor. "He'd sign hundreds of dollar bills and tell the bank president he could come to whatever shows he wanted."

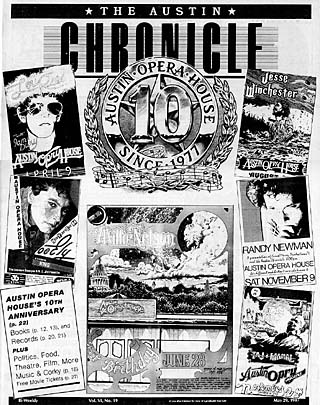

Nelson and O'Connor were in business, 50-50, for a mere $10,000 up front. Better yet, while studying the plots they'd just bought, O'Connor found an additional 13 lots they'd inherited through a sale the bank hadn't covered in the mortgage. With the $60,000 those lots sold for, the Austin Opera House was up and running. At the time, the only viable concert venues for major touring talent were the City Coliseum, Palmer Auditorium, and the Erwin Center. More importantly, the Opera House provided an alternative to the Armadillo.

"Eddie Wilson pretty much had a headlock on the city," says Jim Ramsey, a local concert promoter who often rented the Opera House from O'Connor. "While his was a closed shop, you could walk into the Opera House, cut a deal, and get your feet wet as a promoter."

When the Armadillo finally ended its storied, decade-long run in late 1980, the Opera House was seen by many locals as the last gasp of "Old Austin."

"It was the holdout," says Henry Gonzalez, who first worked at the Armadillo and later stage-managed the Opera House. "When the Armadillo went down, all the other clubs started disappearing. Aesthetically, [the Opera House] and Liberty Lunch were the only ones to carry over the Seventies vibe into the Eighties decline."

They also hung out at another one of O'Connor's clubs. Mostly, the Opera House's vibe was supplied by Nelson's entourage, a constant presence at the door, in the crowd, backstage.

"His Willie thing was a phenomenon," exclaims Wilson. "My hippies couldn't work with Willie's hippies. Tim pulled off what I consider to be one of the world's greatest public relations miracles. To maintain a relationship between his people and that wonderful bunch of Damon Runyan characters that hang around Willie still impresses me. Willie is the Muhammad Ali of white people, yet running in tandem with his crowd is a something a lot of people can't do."

Willie's hippies may have gotten along with the Opera House staff, but promoters running in tandem with O'Connor often found the going difficult, to say the least.

"Tim wasn't a real easy person to get along with in those days," remembers Ramsey. "There would be many times we'd be screaming across the table at each other, and 20 minutes later it would be hugs and kisses. And suffice it to say that in those days, there were plenty of outside influences that dictated someone's personality, to be as polite as I can without casting stones from a glass house."

Gonzalez describes the Tim O'Connor of the Opera House era as a "hard man to get close to," but says that he offered his employees and crews unprecedented latitude. If you did your job and something went wrong anyway, Gonzalez says O'Connor would protect you from angry promoters or artists.

"The screaming, the reputation, a lot of that was a front," asserts Gonzalez. "It was part of the game, because he wouldn't come in until that was the last resort. By the time the problem got to him, his job was to play the heavy."

O'Connor doesn't deny he made his share of enemies at the Opera House, but he also maintains that the concert business was changing so rapidly in the early Eighties that the need to enforce a level of professionalism by any means necessary was that much more important.

"As more acts came to town that had witnessed the growth of the concert industry nationally, the relaxed, laid-back Austin approach wasn't as effective," O'Connor explains. "We had to keep taking things up a notch -- sound, promotion, overall presentation. I'd like to think I was one of the architects of trying to make this town's concerts more professional."

What O'Connor didn't advance very well was peace between concert promoters and neighborhood groups. After Travis Heights homeowners blamed him for cigarette butts left nearby, O'Connor found a commercially zoned lot that bordered the neighborhood and briefly put in a petting zoo. If Bobo the Elephant wasn't message enough, O'Connor told a neighborhood meeting that if they didn't back off, he'd host Nelson's annual Fourth of July picnic in the Opera House parking lot and aim the speakers at their houses.

"Better yet, I told them I'd put on every poster and ad, 'Plenty of free camping in beautiful Travis Heights.' When my lawyer got done kicking me in the leg, that's when things really went downhill," recalls O'Connor. "I really cut my teeth in neighborhood negotiations back there -- in all the wrong ways."

Travis Heights wouldn't be free of O'Connor until 1990. He'd bought Nelson out two years earlier, just before the singer's tax situation got messy, but it wasn't long before O'Connor himself wound up in a bit of IRS trouble; since buying the Opera House in 1977, he'd been filing corporate taxes, but not personal taxes.

"I thought that was the way it was done, but Ms. Martinez at the IRS totally disagreed with my position," says O'Connor of the six-figure penalties he accrued.

With Nelson's own tax problems, O'Connor didn't have time to implement his traditional Plan B and wound up selling the Opera House at a "fire-sale" price.

"Every other time we'd get behind in taxes or I'd miscalculate someway, I'd call Willie and he'd come in and play five dates. We never called them 'benefits,' but we both knew the deal. His draw often kept the doors open."

There was a time when Tim O'Connor didn't have to worry keeping the Opera House's doors open. In the mid-Eighties, Austin's most powerful promoters shared office space at 411 Barton Springs Rd. and formed what later became known as the Ivory Tower collective. O'Connor controlled the Opera House, routinely dealing with Houston-based powerhouse Pace Productions and their Austin liaison, Steve Hauser. After owning five record stores, French Smith controlled Austin's outdoor events, staging Pecan Street and a half-dozen or so other annual festivals while also renting the Opera House for the occasional indoor show. Jim Ramsey booked both the Back Room and a healthy slate of Opera House shows.

"We all found ourselves together one day," says O'Connor. "Instead of coming to work with machetes, we tried a pencil and pad. We were going to see what we could work out together, as opposed to being at each other's throats."

Strength in numbers now meant they weren't bidding against each other, so the only venue Pace could book without working with the newly formed collective was the Erwin Center. What it boiled down to was simple: the collective could pool connections and resources to produce bigger and better shows with more frequency then they could on their own.

"We had the town in a headlock," Ramsey says. "Instead of fighting each other for the same piece of pie, we were cutting the pie up."

Unfortunately, Ramsey says, there were often too many cooks in the kitchen without a head chef. The arrangement lasted less than two years, with Ramsey bailing first, followed shortly after by Smith. Hauser, meanwhile, who'd brought most of the group together, had left early on to start up the successful FreedomFest franchise. O'Connor was left holding the market share of shows in Austin.

"When I was there, my goal was to mediate and to make sure everything made money," says Hauser, a booking agent at the William Morris Agency's Nashville office. "I think Tim always had the best understanding of what the consumer wanted and how to deliver it. We were always running around trying to book as many shows as possible and were most conscious of how much money we could make.

"That wasn't the bottom line with Tim, though. That was unique, and I think a lot of that came from working with Willie. He knew that you didn't always have to make money, that you have to give great product. And great product will make it so that you can eventually make money."

Even if you control a market and wind up making money, as the Ivory Tower collective did, it's often not the kind of money true empires are built on. Even today, promoters often walk away at the end of the year making as little as 5% of the door's receipts. The only way for promoters to make real money is on ancillary goods and services: alcohol, food, a percentage of a band's merchandising, and ticket fees.

In the Opera House days, O'Connor cut his costs and launched a successful business with Brad Meyer by starting Star Tickets; they not only made money selling tickets for other venues, but they were able to keep the money from the Opera House in-house and available. Moreover, O'Connor has also long been Austin's king of the private party, hosting as many 200 private events a year at his three venues.

"I realized long ago that music was the nighttime job and that you had to be making money during the day," reveals O'Connor. "As long as you're doing private parties, you know the money is there up front, and no matter who shows up, the check's clearing. You have to build a base on a fixed income so if you lose it on the concert side you don't go bust."

O'Connor may have entered the Nineties knee-deep in debt to the IRS, but at least the Eighties were behind him. Midway through producing the second Farm Aid, at Manor Downs in 1985, O'Connor got the news his daughter had passed away. Three years later, O'Connor's life changed again, this time by his own choice. After staying out drinking until 4am the evening before a three-day blues festival at the Opera House featuring Bonnie Raitt and Stevie Ray Vaughan, O'Connor says he realized he had two choices.

"I could either walk down to the bar and start drinking again, or be honest and do what I said I'd do -- to produce these shows in a professional manner."

He's been zealously drug- and alcohol-free ever since.

Throughout 1990-91, O'Connor drifted yet again, this time to Minneapolis to work with a group that presented stadium-sized Earth Day concerts featuring acts like Paul McCartney and REM. A year later, Austin came calling again; Jeff Blank from Hudson's on the Bend believed he'd found the land for a restaurant/venue concept he and O'Connor had long discussed. January 1993, they bought 13 acres in Bee Caves and began work on the Backyard and its Live Oak Amphitheater, a nearly 3,000-seat outdoor venue.

Although O'Connor believed he could build a venue that reflected "Old Austin," his venue was at least 15 minutes away from downtown. O'Connor recalls that only one friend, Texicalli Grille's Danny Young, believed it would work. Young told him it was a bird nest on the ground -- he'd only need to pick up the eggs. Skeptics, on the other hand, said concertgoers wouldn't drive that far for a show, particularly from North Austin. Before long, Georgetown's "Only a Conversation Away" slogan became the Backyard's "Only Three Songs Away."

"I liked being in Bee Caves," O'Connor says. "I always wanted to sit behind my desk and be able to tell some artist that had me pulling all the red M&M's out of the bag that he'd never play in this town again."

Although the Backyard wound up proving Austinites would indeed go out of their way for atmosphere and talent, O'Connor's next move brought him downtown. Through an introduction from Jim Ramsey, O'Connor was brought in to consult on a club called the River's Edge, located at Second and Nueces. He found a warehouse with unisex bathrooms and a huge dividing wall.

"It wasn't what they wanted to hear," remembers O'Connor, "but I told them they had a very awkward room that I'd close and start completely over with."

Several months later, the landlord offered him the chance to do just that; after tearing down the wall O'Connor opened the Austin Music Hall with a sign that said "Phase 1."

"People that had been to the first round of shows there because perhaps they knew I was the same guy behind the Backyard, would come to me on the streets afterwards and cuss me out," he says. "The acoustics were horrible, and it was just this terribly hot, smoke-filled room."

Nearly a million dollars of roof-raising renovations later, the Music Hall's Phase 2 was completed in time for South by Southwest '95. And despite the fact that Direct Events had grown nearly 300% in 1994-95 and was on the verge of bankruptcy, O'Connor agreed to buy La Zona Rosa in 1996. After significant renovations, he lost nearly $140,000 its opening year and half that its second.

Even so, merely owning La Zona added value to Direct Events. Now, O'Connor owned and operated four different venues with four different configurations: a 3,000-seat indoor room, a 4,000-seat outdoor space, a 1,400-seat indoor venue, and a smaller club-sized room within La Zona. Not only did it allow Direct Events to lure agents and acts with the promise that they could move through their ranks, it kept the overall business operating 12 months a year, not just the seven months it was safe to stage shows at the Backyard.

Just as vital to Direct Events' success has been O'Connor's agreement with Pace Productions for the Music Hall and Backyard. O'Connor has a history with Pace that predates the production company's move from New Orleans to Houston in the Eighties. Owning the Backyard and Music Hall gave O'Connor an opportunity to formalize their dealings; in 1995, the two companies signed a contract that allowed Pace to co-promote shows in O'Connor's venues.

While this cost Direct Events some independence, the contract reserved O'Connor's right to promote 140 acts on his own that he had longstanding relationships with (artists such as Willie Nelson or Little Feat.) Backed by the national clout of Pace, now part of the larger SFX group, O'Connor believes he's been able to bring more shows to town at competitive prices.

"We've always had a policy that if I knew an act better than somebody else or had a certain kind of relationship, it's probably best I'd make the call," explains O'Connor. "My relationships are based on the old way of doing business, where theirs are on a new, more aggressive, streamlined, let's-buy-the-tour or region approach. On my own, I'm doing one date, while they're buying 40. It's obvious that you get economy of scale working with them."

O'Connor is the first to admit the combination of Pace's deep pockets and his own long-term connections represents a serious hurdle for competing Austin venues. At one point, it wasn't unusual for booking agents working the local market to get 40% more than their asking price after compiling competing bids from Direct Events, Liberty Lunch, and Stubb's. O'Connor denies critics' claims that he's used Pace's muscles to target Stubb's and Liberty Lunch, and maintains that the increased competition he's seen in the past few years has done more to hurt the local concert business than help his own.

"Booking agents not only have more options, but they'll gladly work the rivalry," posits O'Connor. "Everyone ends up paying more, including the ticket buyer. Over the last few years, we've been killing ourselves."

Charles Attal has spent the past five years receiving a crash course in concert economics at Stubb's. Attal co-owns and books both the restaurant's small inside room and Stubb's Waller Creek Amphitheater, a Backyard-style outdoor venue. By flying around the country to meet with agents and sending follow-up packages of barbecue, Attal has earned a reputation within the industry as a dedicated player.

So much so, in fact, that Attal has pried a sizable amount of shows away from Direct Events. He also produces classy and smooth-running shows; as with the Backyard, acts that play Stubb's tell their agents they want to return. And yet, his primary obstacle has been not being able to buy large shows year-round. While he's used venues like the Mercury and Antone's to stage larger shows in the off-season, he also runs the risk those clubs will eventually cut him out of the deal.

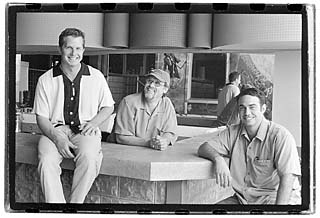

"Not controlling your own destiny is a distinct disadvantage," says O'Connor. Meanwhile, O'Connor has directly helped shape Charlie Jones' destiny. Jones started answering phones for Direct Events in 1993, and just three years later was La Zona Rosa's general manager. When Attal was paying for his own meet-and-greet trips to the coasts, Jones was meeting agents on O'Connor's dime.

"He pretty much taught me 80% of what I know, and the rest comes from the Pace guys we worked with in his office," says Jones, whose MiddleMan Music produces many of the city's largest outdoor concerts and events, from A2K and the Lance Armstrong celebrations to multi-act KGSR Blues Festivals and 101Xfests.

Since O'Connor and Jones both describe their relationship as "father-son," the latter equally close friends with Attal, Jones has been the architect of what could be the new Ivory Tower collective -- a centralized effort from Stubb's, MiddleMan Music, and Direct Events. When Attal faced a weekend's worth of rainouts last season, Jones brokered a deal that allowed both shows to move to La Zona Rosa. Was it a case of O'Connor keeping his enemies close?

"I don't know if you could quite call us enemies," Attal demurs. "He's always held most of the cards, and I've always been the guy fighting to get a few of them."

What nobody expected, Jones included, was O'Connor's recent invitation for Attal to begin booking La Zona Rosa. It's a move that gives Attal year-round booking clout and has already resulted in both La Zona Rosa and Stubb's paying lower prices for shows. And while monopolies are generally bad for the consumer, in the concert business, they tend to work to the ticket buyer's advantage: Promoters paying less for shows typically pass it on to the consumer to increase attendance and thus increase alcohol sales and other ancillary revenue.

"I do think it's going to work to the consumer's benefit," reasons Attal, who now shares office space with Jones. "I'm dealing with the agents on both venues and putting the show where they'll be best presented. I know what I'm going to pay and that's it. We're not bidding shows up 30-40% anymore."

For his part, O'Connor admits he wishes he'd swallowed his pride and called Attal sooner. He sees it as a return to the free flow of information that he found in the Castle Creek days.

"I'm open to the possibility we can do something collectively that we can't on our own -- to protect the Austin market," reasons O'Connor. "Mark my words, if you think it's difficult now, give it 24 months. This scene could change as drastically as it did from the Seventies to the Nineties within just a couple of years. Things are moving that quickly."

As cryptic as his warning may be, it's notable that O'Connor also refers to his new alliance as "solidarity by design of defense." Defense from what? SFX. O'Connor's contract with one of the country's largest promoters is due to expire in December. Whether or not it's renewed, SFX's power is intimidating. They now own 130 venues nationwide, including 44 amphitheaters. Additionally, they can flex the muscle of 1,170 radio stations.

"It's tough to build momentum as an independent anymore," explains O'Connor. "You have to create a niche that's so protected and specialized that it doesn't draw too much attention. Because if you're detected and manage to pierce the bottom of that larger national company's canopy, they're going to come after you."

At this point, there's no timeframe on how long Attal and O'Connor will continue working together. While they appear to be getting along famously, neither side denies their relationship is still a house of cards. O'Connor's fuse may be longer these days, but one crossed signal could end the deal. While it's a poorly kept secret that Attal and his partners are entertaining offers to sell Stubb's, O'Connor's retirement is more likely the deal breaker.

In fact, O'Connor was to retire from day-to-day operations January 1, 2001. Late last year, however, SFX's purchase of the Backyard was a week away from being completed when it was called off. O'Connor claims it's a mystery to him why the deal came off the table, but he maintains the negotiation process hinged on design. While both sides had worked through 98% of the differences, SFX's plan to expand the Backyard clashed with O'Connor's vision of how he wanted to leave the facility.

"I've never had a customer tell me I should cut down a 400-year-old oak tree because the sightlines would be better," he says. "But to get a major company to sit down and have the same general plan -- a plan that doesn't compete with the city or the design of the developments around the facility -- is very challenging. And honestly, for me, it wasn't about money in the end. I'd made concessions to the tune of some serious dollars."

Although O'Connor admits there's still "conversations at different levels" about how the deal might be salvaged, he says a group of well-financed smaller promoters could perhaps team up to purchase the Backyard. Or, he hints, he could wind up settling for less money to merely close the venue and sell the property outright if he can't find the right buyers. In any scenario, Jones and Attal say it would only take a drive to their office to unload the lease to the Austin Music Hall. And yet, Attal says he's not waiting in the parking lot for O'Connor to show up with the paperwork.

"I think he likes the game too much to really be trying to get out," maintains Attal. "I may not know him as well as Charlie [Jones], but I'm certain it's not the money that drives him anymore. It's not about the extra dollar. It's about the excitement. He does it because he loves music and loves the game."

Tim O'Connor believes his funeral will be like many other events he's staged: well-attended.

"I think a fair amount of folks will come," he says. "The way to make money is to offer a drive-through viewing. You could rent a stick to poke me with ... to make sure I'm really dead."

O'Connor isn't serious, but given his thoughts of retirement and recent run of heart troubles, he's indeed been spending time pondering his legacy. And just what might that be?

"My first thought would be that they'd say, 'That's that old guy that's been around forever. He's maybe a little crusty,'" laughs O'Connor. "I think they might also say, 'He sure had a lot of breaks because of his association with Willie Nelson. I'm sure that's what made his career.' But lastly they'd say, I hope, 'I've had a lot of dealings with the guy, and while he's a tough negotiator and a lot of time you can't figure out what he's up to, he's honest. I never heard him not paying an artist or cheating a partner.'

"I think somewhere along the way, people that know me labeled me as a guy that if I said I'd do it, I did it -- at all costs. I don't know if that's bad, but I know I'll get to the mark. I might be tattered and torn up, and a lot of people may be lying behind me, but my attitude is, if you're not helping, get out of the way. I have very little patience for people that fool around in this business or just want to make a buck."

Indeed, says Steve Hauser, if you're looking for O'Connor's legacy, look toward his lack of patience for part-timers and carpetbaggers.

"The battles I had with him at Pace over why we couldn't do a certain event always came back to the same thing, 'That's not what Austin's about,'" says Hauser. "It took until I lived there to understand how unique the city is. Tim recognized that better than anyone. His mission was always to bring entertainment for Austin, not bring Austin entertainment just because it worked in Houston or Dallas. And if you're always looking out for your town and its fans, look what happens. We're talking about a concert promoter 30 years later. That's rarely the case."

Although it's been mostly by his own design, the great irony of Tim O'Connor's career is that it took 30 years for his story to reach his customers -- the people of the city he loves catering to. Few salesmen in any industry deal so long with so many customers that don't know their name. Or maybe it's not ironic at all. Maybe it's yet another O'Connor business strategy. Is he showing his hand to lull competitors into a false sense of security, or is coming clean part of a public relations campaign designed to repair his reputation before he eases into retirement? Perhaps it's all of the above, although he denies there's any real motive at all.

"Do I want to try and change my image? What's done is done. I am what I am," he says. "But I'm at a point in my career and life that whatever I have and haven't done, it feels right to get it out there. And to some degree, it's also about admitting what I've done wrong. I've made some mistakes and enemies, but the other side is I hope I've made some friends and made a little bit of difference in the presentation and the quality of music that comes to Austin.

"Have I done it all by myself? Absolutely not. But it's time to clear the air and say the driving force I have at this point is merely wanting to grow old gracefully. I'd like to pass through whatever time I have left in this industry and in my life and be able to sit back in the rocking chair, should I get that opportunity, and say 'Tim, you didn't do too bad.' That would be good enough for me." ![]()