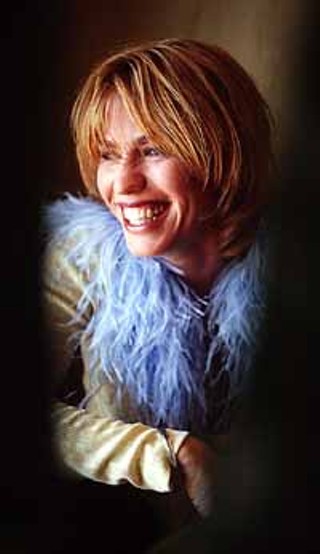

Sara Smile

Sara Hickman, A Woman Waiting to Happen

By Margaret Moser, Fri., May 11, 2001

The secret is the smile.

It starts in her full, peachy-pink lips. Puckers and creases broaden and smooth as the lips expand and curve, bowing upward in a crescent. The mouth parts to reveal ivory teeth, even and glistening. And just where it is least expected, a tiny dimple flirts on the upper right. Julia Roberts wishes she had Sara Hickman's luminous smile.

Hickman knows the value of a smile, so the 38-year-old singer-songwriter-artist-mother-wife-activist bestows it often. It appears whenever she speaks of her two children, her husband, her fans, her tireless community work, her art, and her music. Sometimes, when touching on emotional subjects or talking about answering God's calling, the smile comes with bright tears. Sara Hickman's life is blessed, rich, busy, and yes, occasionally turbulent.

"Go Create Something"

Sara's house in deep South Austin is as full of life as her music. It is a visually appealing space, with a grand, colorful canvas painted by her father dominating a very homey sitting area beside a spacious kitchen. Nearby is what looks like a tiny painting studio, with art supplies and kid-sized table and chairs, decorated in the bold palette of childhood.

In the middle of the house is a living room with piano, and at one end is an office where Hickman's husband Lance is collecting phone messages while his wife consults the calendar about a gig. Baby Iolana is in the midst of her mid-day nap at the other end of the house, where daughter Lily's room is located, a showpiece of small murals painted by Sara and her friends. It's enough to make you wish you were five and your last name was Hickman.

Hickman's parents were both artists, her father a painter and professor and her mother a weaver and sculptor. Their response to the classic childhood cry of "I'm bored" wasn't "go watch TV" but "go create something." She has carried that imperative with her since childhood, and passes it on to her own children.

"My parents always had artists over, smoking cigarettes in these long holders and wearing interesting paisley clothes and playing the piano, staying up late," Hickman says. "It was all very glamorous. My mom had a 12-foot loom in the back of the house and was always weaving, making odd sculptural pieces. I remember thinking everyone lived with art in the house and paintings on the walls.

"A lot of people think of creativity like volunteering -- taking a couple hours out of the week and maybe make cards for their grandmother or whatever. In my family, it was part of your life. Creating was the same thing as going to the bathroom or cooking breakfast. It was just there, all the time.

"I'm trying to pass on to Lily and Iolana that creativity isn't just a 'bonus timeí' where you sit at the table and draw, it should be a way of expressing yourself whenever you feel it. And I am so grateful to my parents for that. Today on the way to school Lily said, 'I love the gray in the sky! Isn't it beautiful?' Yes, it is -- it brings so much depth to see your life that way."

I've Got the Music in Me

So why didn't Hickman choose one of the visual or graphic arts? Her childhood seemed tailor-made for producing a budding artist. That is, as she freely confesses, "kind of a mystery. My family wasn't very musical.

"I've never told anyone this, but I remember a babysitter putting on my dad's Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass record and dancing. And I was laughing and dancing hysterically, I was five or so, and we were having the best time! I think it really sparked something in me."

The next step was piano lessons, but they failed to keep the spark going. "You have to learn some instrument," her mother told her, and took Sara shopping. They left a music store with a guitar. It was the beginning of a lifelong romance between a girl and her instrument.

"I loved the guitar," she enthuses. "It became my best friend. I had a Sears tape recorder and wrote skits, wrote the commercials and everything. I still have tapes from when I was little, announcing 'the watermelon seed spitting contest of the universeí' and you can hear my friends going 'sput, sput, sput.' I wish I still had my first guitar, but in fourth grade I sold it to Grace Das for $10."

Hickman kept following the guitar's siren song through junior high and high school. She tried out several colleges before finishing at North Texas State University in Denton. The university's famous music school included Brave Combo's Carl Finch, who saw something special in the aspiring songwriter.

"Carl made me mix tapes, music from all over the world," she says. "He took me under his wing and said, 'You don't have to be just a girl with a guitar, here's what you can be.' It was a blessing and a curse because he exposed me to all styles. It broadened my horizons musically so much that I do bring in all these quirky elements, and that can be overwhelming. It's like I wanted to taste the whole world but had to start with a spoonful."

While a student, Sara picked up gigs at Poor David's pub in nearby Dallas, and after college gravitated to its musical nexus in the Deep Ellum district. In the late Eighties, it was a vibrant scene, and Hickman rose to the front of its urban ranks with her spiritually romantic, intelligently optimistic songs. She scored a major-label contract with Elektra for her debut recording, Equal Scary People. It garnered the kind of favorable notices most artists only hope for.

Her popularity was on the rise. She regularly collected top awards from the Dallas Observer music poll and played rigorously. She had also recorded a song for the Arachnophobia soundtrack ("not even one of mine -- Martika co-wrote it"). Elektra had suggested it would be an excellent addition to second LP Shortstop. Sara disagreed and completed the album without the song, but not without fallout: "It was the first time I got that 'uppity artist' vibe." It wouldn't be the last.

Shortstop came out in 1992 amid good times -- tours, VH1 videos, more music awards from the Observer. Her category-defying music -- too rock to be folk, too pop to be rock, too quirky to package and sell -- cultivated an ardent following. It was pure Sara Hickman, and her fans loved it. Soon she was at work on her third Elektra album.

"I was supposed to be the girl-next-door Tracy Chapman," she remembers.

This time, the record boasted Hickman, Paul Fox (the Wallflowers), and Angelo Badalamenti (Twin Peaks) as producers, a solid team with seemingly great promise. No one was prepared to hear that the album Elektra spent $300,000 on was going to be shelved, least of all Hickman.

"My Songs Are Hostage"

"I felt like I failed. I let down my fans and family and friends," Hickman says. "The label president said it was 'three records in one.' There was a clause I couldn't re-record the songs for five years."

Devastated, Sara turned to those close to her and once again her mother had the sage advice: "Call them and see if you can buy the masters." Sara summoned her courage and called Elektra's attorney.

"'Hi, this is Sara Hickman,'" she recounts. "'I know the label just dropped me, but do you have a picture of your family on your desk?' 'Uh-huh.' 'At the end of the day do you go home to your family?' 'Uh-huh.' 'Well, I don't have a family. I don't have children. I don't have a picture on my desk because my family and my children are my songs. And you are practically holding my songs hostage. I don't know what I am going to do if I can't get my songs back. This is really important to me. I will raise whatever amount you want.' Then I started crying and hung up the phone."

The move was gutsy, the tears were girly, and it worked. The label agreed to let the masters go for $100,000. Hickman was elated, although she faced one small obstacle: she had no money, least of all $100,000. Thus Necessary Angels was born.

Anyone who contributed $100 to her cause became a "Necessary Angel" and would get a numbered bracelet, a copy of the CD, their name in the CD booklet, and an invitation to a private party for its release. Friends like Michelle Shocked and Trout Fishing in America were among those giving $100 for the wrist halo. Hickman, meanwhile, was liquidating possessions left and right.

"I sold my house, sold my car, sold my antique salt & pepper collection," she says. "I was homeless, living with friends, my stuff was in storage, and I broke up with my boyfriend."

And she raised $40,000. It was less than half the amount needed, but Jac Holzman, the Elektra founder who had gone on to Discovery Records, took an interest in the album. Mysteriously, Elektra's asking price cut in half, to $50,000, and the dream drew closer. Hickman signed to Discovery, and the price dropped to $25,000.

Today she calls the party and celebration for 1994's Necessary Angels "the most amazing moment of my musical career." She had rescued her songs, paid off the lawyers, and donated the rest to the Romanian Children's Fund. She also would not release another solo album until 1997.

Nineteen ninety-five was hardly fallow. She moved to Austin from Dallas. A personal project dubbed the Domestic Science Club was picked up for distribution on Discovery by former necessary angel Jac Holzman. A second recording by the trio of young women -- Hickman, Robin Lacy, and Patty Lege -- followed in 1996. Tours solo and with Nanci Griffith furthered her career, as did a new recording project.

Hickman exited the studio with new material and a healthy dose of covers on 1997's Misfits and even more new songs on 1998's Two Kinds of Laughter, produced by Adrian Belew. One marriage had gone and a baby had come. Soon enough, another marriage would come, and with it a second baby.

A Quieter Gift

"About three years ago I was going through a really hard time and I went to my minister of the church and said, 'I feel like God's calling me into the ministry,'" Hickman relates. "'I am thinking of going into the Unity Church because I want to work with all kinds of people.

"She said, 'Well, you'd probably like that, but you're already being a minister. You touch more people with your gifts from God than if you were doing what I do. You're on the right path, keep doing what you do.'

"It really made me feel like, 'Yeah, it is a ministry and I'm not gonna give it up.' Maybe I don't 'fit' anywhere, and sometimes that hurts, I'm not successful in that sense. But I am successful in this whole other unique way, and that's how I look at it. My music is a quieter gift between me and the people who like what I am doing. Instead of being the outsider looking in at a party, I'm having my own party in the street."

It's not the first time Sara's eyes well with tears as she speaks. Her estimation of her music as "a quieter gift" is disarmingly modest. Next to her smile, music is what Sara gives most freely. And whether assisting her church choir in producing a CD or flying to Romania, Hickman takes her tithing as seriously as her music and her children. Among the organizations and programs benefiting from her commitment are Austin Mother's Milk Bank, Arts for People, Hug the Homeless, Hill Country Youth Ranch, the Mautner Project, Hill Elementary School, Umlauf Sculpture Garden, Kerrville Songwriting School, and Habitat for Humanity.

Hickman got certified to teach parenting classes and makes time to do so. In 1991, a homeless woman in her Dallas neighborhood inspired the song and video "Joy," directed by Sara and winner of a USA Film Festival award. She co-produced a PBS documentary titled Take It Like a Man. Last year, Hickman won an award from Humana for speaking on women's health. She designs her own CD art but also has time to do it for a friend. Changing public opinion about the homeless is also high on her agenda. "In March I was playing at La Zona Rosa," she explains. "The homeless people were asleep under that overhang next door and so I went over and asked, what do you need tonight? 'Oh man, some blanketsí' so I went home and gathered some for them. The next day Lily and I went to Target and bought gloves, toothbrushes, toothpaste ... Lily wanted to get them bottles of water so we did. We made little packages and handed them out.

"Lily gets out with me and she hands out the bags and she knows that these are people. Whatever their circumstances, however they got there, they still suffer and need to feel love and compassion. I have so much, and that other stuff I can buy; the love is free to give."

The Hickman Monologues

Even with love to give, Hickman's schedule gets a little frantic. Gigs must be booked, such as her upcoming August appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival. Tours must be undertaken, like the Kerrville Folk Festival Cruise she will play on in January 2002. Her music for babies and children is like "having a third child." Between her recording the kids' CDs Newborn and Toddler, she delivered a spectacular collection of songs last year called Spiritual Appliances.

"Life goes so quickly now that I am a mom," Hickman notes. "I have to have time management. I have two children. I need to spend time with them together and separately, and I need to spend time with my husband. And I need to spend time with all four of us. And yet I have to spend time writing, overseeing the people that help me work, and I still do my own accounting. It's like having a tiny little empire. It's exciting and completely exhausting."

Sara gets plenty of help from Lance, who sometimes performs with her. She is quick to give him credit for helping her regain balance in her life, but is especially grateful to him for one thing: surprising her with tickets to see Linda Ellerbee in The Vagina Monologues, which turned her thinking around.

"Now I talk about vaginas onstage all the time," she says. "Before I saw The Vagina Monologues I wouldn't say 'cunt' or 'pussy.' To me, they were like little blows to women -- nasty, naughty, ugly, and smelly. My new thing is that this is not the peace sign" -- Sara holds her index and middle fingers in a classic V sign -- "This means power to the vagina. I'll be in the middle of a song and go into a rap about the vagina because I love to celebrate women. When I perform 'Woman Waiting to Happen' live it has 10 times the power it does on the record. I wrote it with Barbara K, an anthem about women now, not an angry thing, but celebrating women."

As if in agreement, a muffled cry comes from down the hall. Lance goes to tend the baby, and appears moments later holding a sleepy-eyed Iolana Rose. Her downy blond hair frames her chubby little face, which splits into a wide, sweet smile when she joins her mother on the couch. The keyring Iolana grabs becomes a rhythm instrument as she shakes it vigorously and emits little peeps. She is, as to be expected, a happy baby: curious, incipiently musical, and intelligent.

And a lot like her mother. ![]()

Sara Hickman plays the Rockin' the Cradle free Mother's Day concert in Waterloo Park Sunday, May 13, with Kelly Willis, Brave Combo, Foamy, Eddie Coker, and Rue La-La, noon-7pm.