After the Last Hurrah

Beaver Nelson, Older, Wiser, Scruffier, Returns With His 'Little Brother' in Tow

By Jim Caligiuri, Fri., Nov. 10, 2000

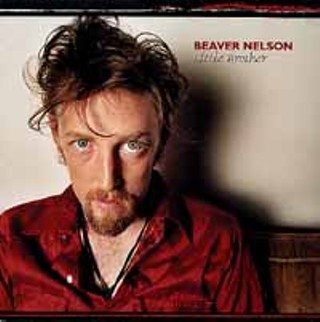

Take a close look at the cover of Beaver Nelson's new compact disc, Little Brother. His stare is fixed straight at you. His hair is disheveled, strewn in all directions. His shirt is unbuttoned, adding to his unkempt appearance. His is a look somewhere between deer-in-the-headlights and police lineup. He's the very definition of "scruffy." Thing is, it's not a fashion statement. What it is, is an accurate representation of the artist inside.

Little Brother is the 29-year-old Nelson's second album, which comes two years after his outstanding debut, The Last Hurrah. On his new album, the local favorite takes on a variety of musical styles -- country, folk, rock, blues -- and bundles them up in an appealing mix that, beyond the simple, moving lyrics and refreshing vigor, breaks no new musical ground. While The Last Hurrah was more acoustic-based, a singer-songwriter's album, Little Brother is a step in another direction. He's replaced the fiddle and mandolin with horns and organ, and along with his producer Scrappy Jud Newcomb, forged an honest-to-goodness rock & roll album. It's both more electric and more electrifying.

This is not surprising, given that Nelson's tenure in the music business has been traumatic to say the least. The tale of how he got to the point of releasing The Last Hurrah is one of heartbreak, unbelievable twists and turns inside the music business machinery, and more than a couple of false starts over the course of nearly 10 years. But the story had a happy ending; the album was a success, selling enough copies that Nelson is actually making some money from it now. The making of Little Brother mirrored some of the same music business turmoil he experienced previously, yet it was compressed into a much shorter time frame.

"The first record came out," he recalls, "and got some decent press. There were some people who were waiting for a Beaver Nelson record. I took the angle that no one would know who I was. It's almost always a good approach to look at it, as there's a whole world of people who don't know anything about you. It's always good to keep that in mind. But so far, we've sold more records than we originally thought we would."

Thing is, Nelson says that if he hadn't gone through all the confusion and heartbreak of making the first album, there never would have been a second. After The Last Hurrah was released, Nelson went on a new journey of sorts to put all the unpleasantness he'd experienced with record labels -- and the people who work for them -- behind him. He toured some, mostly in the Midwest, but on the East Coast as well. The album received almost universal critical acclaim and won him many fans.

Yet, when it came time to make a second album a year later, some funny things started happening. Not funny as in "ha ha," funny as in unfortunate. It seems Nelson's life in the music business was meant to be one of unlucky breaks and ill-timed decisions.

"My thought was that we had a certain amount of momentum with The Last Hurrah, so let's get another one out there quick," he explains. "We were ready to go. We had the songs. The band was solidifying. We had a budget. We had our meetings. We had it set up."

That's when Matt Eskey at Freedom Records, the local indie label that released The Last Hurrah and was onboard to do its follow-up, decided to fold his label. Two weeks before Nelson was due to enter the studio.

"I don't blame him," states Nelson. "He did what he had to do. He put out a record and to have as much success as we did is great, but when success is breaking even, I understood. The money you have to spend to just get to 'breaking even' is unbelievable. One bad move and you can fail. So when success is breaking even, it's tough. I saw his point of view."

Nelson proceeded to get a loan and record what has become Little Brother. When he was finished, Nelson started shopping the album around, getting lots of "maybes" and "we'd love to do this, but we don't know yet," but nothing solid, and no major label interest. Just when things were looking bleak, Jacknife Enterprises, a local music business firm that dealt in national radio promotion and artist management, decided to close up shop. They were his management team.

"Within two months of finishing the record, Jacknife closed down and there went my management," sighs Nelson. "There's no ill will whatsoever, but it sure seemed like the timing couldn't be worse."

He chuckles.

"There was a time where everything was going against me, but there were also times when it seemed like nothing could go wrong," he says philosophically. "Those were some real familiar feelings. I knew the way I had dealt with stuff before, and not much of it was positive. I just kept holding on to the notion that I'm so much better than I was before. People seemed to like my record, they liked my songs, and there was something tangible here. I was hearing from a succession of labels that were interested in doing something with the new record up until South by Southwest of this year. If I'd heard a big silence for four or five months after we made the record, I don't think I would have dealt with it the way that I did. But I heard from people who were interested, and as it turns out, not one of them did or could put the record out."

It was during SXSW, actually, that Nelson had a chance encounter with an old acquaintance that eventually led to his new record label.

"Everything was kind of crushing around me," he recounts. "It was a very heavy day on Saturday during SXSW. I head over to the Continental, 'cause I'm playing Mojo Nixon's daytime show. I've got a 2pm set. We played like six songs and it was blazing from the get-go. It was just one of those days. Afterwards, over wanders two guys, Jeffrey Reed and Chris Hudson."

Reed, it turns out, engineered a recording session Nelson had done in the days before the release of The Last Hurrah, though they hadn't seen each other in years. Hudson, meanwhile, is the cousin of Cary Hudson, one of the main forces behind Mississippi roots rockers Blue Mountain. It's Chris Hudson who also runs a small indie label in Monticello, Miss., called Black Dog that has released albums by Blue Mountain, Marah, and others. Reed and Hudson were looking for acts to bring into their studio, which they use to record artists for the label.

"When they said they were in Monticello, my jaw hit the floor," laughs Nelson. "That's where my father grew up. So now I have to go there. I used to spend my summers there when I grew up. We knew all of the same people; most of them are my relatives. So now I have to visit the studio. They agreed to let me demo some songs. Three weeks later, me and Scrappy head over to Mississippi and record five songs. And while we're there, we check out the label. We had a deal with this other label, but eventually that fell through and Black Dog agreed to put the record out."

With the ball rolling once again, artwork, final mixes, and mastering were completed quickly. Little Brother followed in September, once again to rave reviews. Which is appropriate: Little Brother is easily one of the best albums to come out of Austin this year. Adding to the upswing, Nelson and his wife Stephanie are expecting their first child in about a month. Not that he isn't fully committed to making this album a success; touring and promoting the album as much as he can are a way of life.

"If I'm doing my job," Nelson explains, "I'm probably going to say things that almost everybody has thought about. I'm just gonna say it in a way that no one has said before, and I hope that way of saying it sheds some new light on a well-documented state of mind or whatever. I'd like to think that maybe from having listened to these songs, we understand something a little bit better about human nature or about the way we all think. I would like to think that.

"That's what I'm trying to do. I know that I'm doing something, as a body of work, that's connecting with people, and that's all I can hope for." ![]()

Beaver Nelson plays Flipnotics on Friday, November 10.