Golden Arm Symphony

Graham Reynolds'

By Raoul Hernandez, Fri., Feb. 11, 2000

Prelude: Scherzo

Little does he know it, but Keith Reynolds is performing his pratfalls in the right place. Younger sibling of this evening's guest of honor, Golden Arm Trio's Graham Reynolds, Keith opens his brother's well-attended CD release party and buffet dinner with a bruising 45-minute impression of the late comedian Chris Farley envisioned as an earnest, acoustic guitar-wielding Austin singer-songwriter. Well, maybe "earnest" is the wrong word.

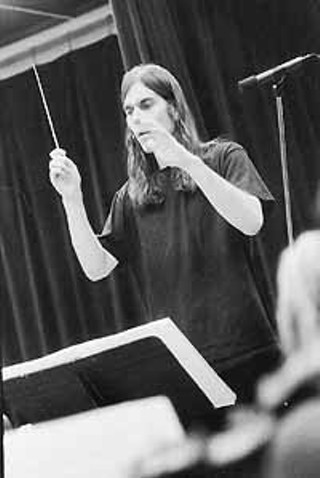

Singing show tunes and old-timey Americana requested by the audience via a menu passed out beforehand, the stout, blond music man throws himself around the Ritz's upstairs stage space, a smallish room that slants up and back with bleacher-style seating, like he was demolishing a Saturday Night Live set-piece. Graham, Abbott to Keith's Costello -- appearing taller than he really is thanks to his lanky frame and long, brown hair (combed forward onto the lapels of his double-breasted, pin-striped suit), and looking somewhat severe with his thick, Bela Lugosi eyebrows -- looks amused. Behind him, in the audience, are what one hopes are at least two more amused, if not slightly concerned, expressions: those of their parents.

Fortunately, this Sixth Street live music venue is the perfect setting for such a spectacle. Opened in 1974 as a downtown alternative to the Armadillo, precursor to Liberty Lunch in its anything-but-the-kitchen-sink booking policy, even onetime home to Esther's Follies, the Ritz lends the scene some vintage Austin: a relaxed yet energized surreality. Voices rise to meet martini glasses in constant salute, the din of the crowd inversely matching the dim of the lights.

Host Reynolds shakes hands with a multitude of well-wishers and friends, as Keith gingerly points out some newly acquired sore spots to his girlfriend, and the Tosca String Quartet readies for its turn at center stage. Another Saturday night soirée in the City of Music.

"Could everyone please SHUT UP!" bellows Cruella De Vil's shrill, meaner sister from somewhere inside the crowd. The Tosca String Quartet -- Leigh Mahoney and Lara Hicks, violins, Ames Asbell, viola, and Sara Nelson, cello -- continue their subdued second number. Seated in a black crescent (chairs, outfits, and music stands) in front of the Golden Arm Trio's equipment, Glover Gill's best local musical creation bows a deep, mournful sound.

Standing just off to the side next to his keyboards, Graham Reynolds watches the four women with keen intensity, listening to compositions from tonight's fêted Why the Sea Is Salt. It's something of a battle, bar noise versus Bartok, but the half-hour set culminates with a still and stirring version of the new CD's main theme, "The Ship at the Bottom of the Sea." As Mahoney and Ames play the tune's final notes, they both look up at Reynolds, eyes big and searching for approval. Giving them due ovation along with the rest of the boisterous, cheering crowd, the pianist grins wide and nods his head. In the room's roar, Ames mouths, "Thank you."

"Tosca String Quartet!" announces Reynolds triumphantly. "Tosca String Quartet!" Approval is all around, hooting and whistling. When he later seeks some encouragement for his own musical vessel following a short set break, neither the audience nor their enthusiasm has diminished.

"Hello, we're Golden Arm Trio," says Reynolds into the microphone bent over his piano, a vibes player, stand-up bassist, violinist, and tenor saxophonist all taking their places around his drum kit and keyboards. "We have a new CD. I hope you buy it."

And they're off, Reynolds opening with a short, solo piano statement before swiveling around on his tool and pounding out a beat on the drums as the band takes off after him on a mad klezmer chase. Alternating busy bursts of energy with slower, more thoughtful pieces, wherein Reynolds caresses the ivories like precious bone while violin and sax polish their own jeweled sound, the Golden Arm Trio are both the airborne cascade of notes in mid-waterfall and the violent smash of crescendos in the lagoon below. The crowd likes it, too; they're buying lots of CDs.

"This one's not on our new CD," exclaims Reynolds, the band launching into orbit a Golden Arm favorite, "The Cantina Band" from Star Wars. The crowd goes Ewok.

On the evening's last number, Reynolds plays both piano and drums momentarily, the vibes and violin weaving a delicate, silken web of remorse. At the conclusion, it's hugs and backslaps all around, a small harem of women congratulating Reynolds individually.

"Girls," winks Reynolds. "Golden Arm Trio gets females."

Andante

Up on North Loop, back among the wooden, two-bedroom ramshackles where rent is still cheap (momentarily), lives Reynolds the composer. If not for the mailbox, you'd miss the house entirely. When the door opens into a navy blue living room with copious shelving, books and bigger books galore, bug-eyed modern art bulging out from every wall, it's impossible not to look back at the drab doorway through which you just entered. This is an environment created/decorated/molded to nurture creativity. Reynolds boasts that the house was used recently as a venue for Austin's annual FronteraFest, the local theatre community's version of South by Southwest. He and his roommate sponsored a band, one in which Reynolds and his co-conspirators each played one of the house's five different rooms -- at the same time.

"The bassoon was in the bathroom," grins Reynolds. "That was pretty cool."

So's his room, a home within a studio. Sitting down at the keyboards butted up against the foot of his bed -- across from his drum kit and stand-up wall piano -- he shuffles the papers that have overtaken his life since November: his symphony. He's got six days before its first rehearsal with a 40-piece orchestra and just under three weeks before its premiere (and possible only performance) at Austin's Scottish Rite Theatre. Paired with a second symphony composed by Peter Stopschinski, keyboardist for local bebop punk rock band Brown Whörnet, Reynolds is taking it down to the wire.

"I fall asleep working on it, and I wake up working on it," he says shaking his head.

A symphony? Who writes symphonies? Why would you even want to write a symphony? And the really important question --

"Why does Golden Arm Trio get girls at its gigs?" repeats Reynolds. "Because we have melodies and straight-ahead beats."

Not exactly something often found in avant-garde jazz.

"I wouldn't necessarily call us jazz," shrugs Reynolds. "I've stopped resisting being called that, because there's no word that tells people any more about us than that does, although most people say, "I like you guys, and I usually hate jazz.'

"We get the "avant-garde' label, because I'll play clusters and bang on the piano and things like that," he says above his best Cecil Taylor piano demonstration. "We get the jazz label, because we have a saxophone and improvise -- even if all the places we're drawing from are predominantly not jazz. As far as the obvious references, I draw more from classical than from jazz."

Though not classically trained, Reynolds began taking piano lessons when he was five, continuing into his first year at his home state's Connecticut College. "I took straight-ahead piano lessons till I was 12. By then, my brother and I had both started improvising so much and composing that our teacher recommended that we get a jazz teacher instead."

Following said advice, he chose as his training ground one of those seedy basement jazz dens of iniquity.

"My mom had a day care in the house, which is quite a way to grow up," chuckles Reynolds in his nasal voice -- rounded rather than flat, calming. "My room was small growing up, and I had a crib next to my bed, all my life. I'd be sleeping and my mom would come in with a mother and her baby, change the diaper, and put the kid to bed for a nap, and I'd sleep through all that. I'd have marching bands outside my door at 7am. My brother and I would play music with the kids a lot, so it was a constant presence in our lives."

A road trip through Austin convinced Reynolds that the Texas state capital was ripe for his post-pediatric musical career, so after graduating in the spring of 1993, he moved to a city where the cost of living was once chicken feed compared to his other objects of flirtation: San Francisco and New York. Here in Austin, he conceived the Golden Arm Trio, a playful yet adventurous carousel of revolving musicians and evolving sounds; one performance might feature a duo bopping fast and fierce, the next a full band running through the entire score to Star Wars. R2D2 and a few other small, plastic George Lucas trademarks sit behind Reynolds on an extensive CD/LP shelving system.

"We've done a couple shows of all Star Wars music," he says. "The loudest crowds we've ever gotten have been at those shows."

If the direct line between the highest-grossing film of all time and Sergei Eisenstein's 75-year-old silent film classic The Battleship Potemkin is a little tenuous to film scholars, then Reynolds walks the high wire with eyes closed. Shortly after the release of Golden Arm Trio's self-titled debut in 1998, Reynolds composed his own score for Potemkin and performed it with his band as part of the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema's inspired teaming of silent films and live, original music scores from local acts. Whereas The Golden Arm Trio CD snuck two classical pieces (Chopin and Prokofiev) among the 26 other kamikaze compositions, there were no strings.

"The first time I wrote for strings on any extensive level was for Battleship Potemkin," explains Reynolds. "I'd played a few shows improvising with string players, but that was the first full-on effort with a string section. Even in high school, I was always playing these concerts with people who didn't improvise, so I was always having to show them what to play. Now, I have all these classical players who don't improvise -- or that's not what they're used to doing -- and it's a whole different ballgame. I've learned to write more, and they've learned to improvise more. We've all come a long way in both directions."

Still, even Pete Townshend never attempted a symphony -- that was Sir Paul (McCartney).

"The doorway to classical music for a lot of people, partially including me -- people from my generation -- is soundtracks like Star Wars," posits Reynolds. "I listen to a lot of early 20th-century music -- Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Shostakovich -- and you listen to stuff like that, and you can hear every piece of music that John Williams ripped off for Star Wars. I went and saw the UT Symphony recently, and they played Holst's The Planets and 'Mars' is [The Empire Strikes Back's] 'The Imperial March.' You can see the Millennium Falcon, practically."

So, if Austin Symphony conductor Peter Bay shows up to your symphony, will he be pointing fingers and making accusations?

"I discovered that in one of my string quartets," laughs Reynolds. "I knew when I wrote it, 'This sounds so familiar.' I kept playing it for people and saying, 'What is this?' And people were like, 'Uh, I don't recognize it.' So, finally, a week ago, I put in this Liszt CD. It's this great piano and orchestra piece. It also happens to be one of my string quartets -- one that didn't end up on Why the Sea Is Salt, thankfully."

Reynolds plays a few brief snippets from his symphony, and like a camera lens narrowing its focus to a pinpoint, the frequent Golden Arm practice space slowly fades except for a reading lamp lighting the pianist's long, well-sculpted hands on the keyboard.

"If you were really looking closely," he smiles, "you could hear where I was drawing from. But it's not like I'm ripping off melodies. Though, yeah, sometimes one of the violins will say, 'You know, you oughta give Prokofiev a break!'"

Menuetto

Graham Reynolds and Peter Stopschinski probably have many things in common, but three in particular stand out: Both are pianists, both are composers, and both are in popular local bands that draw at Emo's as well as the Alamo Drafthouse. Only Stopschinski works as a cook for Austin's celebrated movie-house-cum-grub-pub, however (Reynolds cleans homes several days a week), and it was this Texan son of a piano teacher's unofficial major at UT, Brown Whörnet, that scored the series' second dinner & show combo, Nosferatu.

After ST 37's thundering Metropolis, and Brown Whörnet's teeth-gritting vampire slaying (reprised last year), voyaged Potemkin, but even before Reynolds' and Stopschinski's bands collaborated on scoring the first dinosaur claymation epic The Lost World in September, the two budding classicists had already premiered the precursor to their symphony.

"Last year, I heard that [Graham] was writing some string quartets," says the classically trained Stopschinski, who received a degree in music composition from UT in 1995. "Brown Whörnet had played shows with Golden Arm Trio, so I knew him. I called him and said I had written some string quartets, too. It turned out we were both lying; neither of us had written anything. He was telling people he was writing string quartets to make it happen -- force him to do it. I was telling him the same thing so I could join in with him, knowing that I would also write them when I had to."

The results, according to a Chronicle review, were "steamy. -- Collaborations that reap results of this level are not common enough" ["Live Shots," July 20], and if a private CD pressing of The Tosca String Quartet Plays the Music of Graham Reynolds and Peter Stopschinski, recorded for the participants during the show's only performance at the Hyde Park Theatre last June, is apt representation, the two sets were stunning.

"That came about because I knew a couple of the [Tosca] girls from UT," explains Stopschinski, "so I asked Sara to play the cello. She said, 'I'm not coming unless I can bring my whole quartet.' We were like, 'Oh? Well, we can arrange that! That's no problem.' It all just worked out toooo good, and we had a really successful concert. I'm still amazed how well it went down.

"That night, after the concert, Graham said, 'We need to write a symphony, soon -- get an orchestra together and play 'em.' Ever since then, we've been working on it."

Asked to assess Reynolds' compositional skills, Tosca String Quartet's first violin Leigh Mahoney, whose 3 1/2-year-old musical endeavor counts Alejandro Escovedo, Jon Dee Graham, and Shawn Colvin among its once and future clients, says the group has taken the composer's work to heart.

"It's not that we have to forget about things that we've learned," she says. "It's that he's a new composer and he has a different approach to his notations. The story is a little bit more clear in his music than in other music that I've played. These symphonies prove that he's constantly learning -- improving his compositional skills. He's the only person I know who's written string quartets we can play in a bar."

Bill Elm, who sponsored Reynolds as a Friend of Dean Martinez when the local Giant Sand spin-off needed an organist to tour 1999's instrumental sleeper Atardecer, points out that his composer amigo was integral to FODM's Alamo Drafthouse silent film series contribution, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Reynolds also contributes a composition and his playing to the group's upcoming release, A Place in the Sun, which revolves around Caligari's creepy main theme.

"Does he have a natural talent for this? I would say he does," affirms Elm. "The String Quartets were amazing. I was very impressed. The only thing I wish is that he had been able to play with them. The symphony should be pretty cool."

"Graham's talent is difficult to assess," puzzles Stopschinski. "It's pretty broad. So many people write music, especially here in Austin, but you notice that many of them are locked in this sound or style; somehow the desire to find one's voice limits all other possibilities. With Graham, he's one of those rare exceptions that doesn't let style determine what his sound is gonna be."

Could an expert recognize your symphonies as first efforts?

"Maybe," admits Stopschinski. "I took my symphony to my stepfather. He's an amazing classical musician -- the very first dean of music at Baylor. He's 87 years old and amazing. From Austria; went to school in St. Petersburg in the 1930s. This is when Shostakovich and Prokofiev were still hanging out there. He conducted one world premiere of a Shostakovich piano concerto with Shostakovich playing the piano. This is a guy who used to hang out with Shostakovich -- they'd get coffee together!

"There was a point in Shostakovich's career when the Communists were coming into power, and he was still the main composer in Russia. He had an opera that was just opening and a symphony that was in rehearsal at the same time. Well, Stalin goes to see the opera, and he happens to sit really close to the brass section, which has this big, extended part -- this really obnoxious, dissonant music. Well, Stalin got up and walked out.

"After that, Shostakovich's career was in the dumps, and he had to withdraw this other symphony that was in rehearsal. My stepdad had Shostakovich play that symphony on the piano for him, alone. This symphony that wasn't heard for 30 years after that. My stepdad was privy to that.

"So, this is a man who knows a lot. When I brought him my symphony, he suggested that I start with something smaller and not go for such a grand work. He could tell mine was a first symphony."

Maestoso

It's Super Bowl Sunday afternoon, and even though the sun shines, the chill air burns your ears. The UT campus is quiet, but one can feel all that young male testosterone coming to a boil. Two o'clock rings from the bell tower. Approaching the F. Loren Winship Drama Building, music emanates from behind its thick stone walls; inside, a cacophony of sound from the music room's open door chases Reynolds down the dark, carpeted hallway. You'd never guess this was his first symphony -- or better yet, the first rehearsal for his first symphony.

"We've got an orchestra in there!" he says wild-eyed, hands waving. Cool as a first-time father whose wife's water just broke.

Through the fluorescent white room's heavy blue curtains, some 30 instruments warming up is indeed enough to make any man giddy. Returning moments later, Reynolds jumps onto a yellow box at the front of his orchestra! and opens up with a joke.

"I don't know how to conduct -- "

A laugh goes up. Maybe it wasn't a gag. After Mirandizing the lot of them -- eight violins, three cellos, two clarinets, bassoons, flutes, French horns, bass, percussionists, plus an oboe, tuba, and trombone -- up go his arms, and with the conductor's baton, so does the music. At first, it's just the two flutes and a reed or two, but soon the violins lie down beside them. Before the spell can take, poof!, the movement is over. Is that it? Cautious smiles say "Yes."

The second movement also starts low and slow, the bassists bowing a sad intro. The cellists begin to giggle.

"Wait, wait," waves Reynolds, the music stopping for a laugh. "I forgot -- "

Some classical gobbledygook about measures, which doesn't deter the bassist from beginning again. This time, the cellists start playing rather than giggling, and are bolstered by more strings. It's a pensive piece, thoughtful with somber winter tones, and continues until almost all the musicians in the room are coaxing sound from their instruments. Building like the rumble of an earthquake, the drums crash at the crescendo and silence the uprising, the cellists and violins the only survivors. This pattern of peaks and vallleys continues. Then, silence.

"Next time, we'll take it faster," announces Reynolds.

This time, it's the French horns that introduce the piece -- a new movement. The tuba rises to greet his brass peers, but before it can get there, Reynolds is down on the floor helping the violin section annotate his score.

"Sorry 'bout that," says the conductor, climbing back onto the box and lifting his arms to begin again.

This time the clarinet breezes through the room, the bass clarinet struggling to keep up, and the snare drum egging both of them on. It's a bouncing, animated number, with the tuba boo-booping, and the strings making a rather tense response. The cymbals keeps a careful eye on both. Reynolds, meanwhile, has locked stares with his score, his arms moving up and down mechanically. They stop when the bass clarinet misses his cue.

"That's you," says Reynolds, pointing.

They go again, only this time the violins miss their cue.

"You guys came in two measures too early," says the composer patiently.

An almost pastoral piece blossoms soon after, the violins lush, elegant, as if to soothe the savage beast. The cold bite of the season snaps next, muted strings giving off an icy stillness, followed by a familiar klezmer-type march that steps in time to the drummer's rat-a-tat-tat. Currents and crosscurrents rush by, Reynolds losing his place once or twice and looking up in confusion only to find no one paying him any attention because they're busy reading the score. They just keep playing.

At the hour mark, they stop, and Peter Stopschinski, in a pair of pajama bottoms and T-shirt, magically appears for the passing of the baton. As he prepares for his third of the two-hour rehearsal, Reynolds makes his way over to where the classroom's one-piece desk/chairs have been shoved into a corner, fixes a gaze on his chronicler, and lets out a relieved sigh.

"We made it through."

Finale: Allegro

By now, the Super Bowl has started and it's even quieter and colder on campus. Walking up the Drag, Reynolds agrees to help this classical music novice pick out some choice CDs at Tower Records. Chopin's 21 Nocturnes and 26 Preludes are no problem, and after a bit of searching, Reynolds finds one of his main inspirations, a double disc of Ravel's Complete Piano Works on Sony Classical. Both prove sound investments. No luck finding the right Shostakovich, however.

Ducking into a Thai place not far down the Drag from where Raul's used to punk rock, Reynolds is clearly tired. Two hours' sleep is all that stood between finishing his symphony and dropping $50 for a 90-minute Kinko's copying binge that produced more than 800 symphonic pages that morning. "I've been at Kinko's a lot lately," he chuckles.

So, how'd the rehearsal go?

"Reasonably well," he smiles wearily. "I lifted my hands and they started playing."

Is it what you'd heard in your head?

"It was great to hear it. It sounded pretty much the way I was expecting it to, which was nice. That's always a relief. That happened with the String Quartets: "Oh, that sounds the way I meant it to.'"

This whole project has been somewhat by the seat of your pants, hasn't it? Two rehearsals and a run-through the day of?

"Peter's gonna have a harder time with the short rehearsal schedule, 'cause his is so complex. Mine's pretty straighforward. Since we can get through it, it's now just a matter of tweaking. But I know that it works basically, so that concern, we're past it."

Maybe so, but a few days later Stopschinski reveals that a UT student conductor has been hired to present the symphonies on Saturday. Add another name to the payroll.

"For unknown composers to have an orchestra play their music and pay them is something in itself," remarks Reynolds.

Confirming reports that he's talked to New York's avant-skronk indie jazz label Knitting Factory about putting out the next Golden Arm Trio CD ("I want it to sound like the Latin Playboys -- more produced; I've got a looong list of ideas for upcoming albums"), Reynolds looks wistful for just a moment. You can almost hear the credits roll and classical music come up.

"Yeah, it would be nice," he says softly. "Our visibility would be so much greater. I have every ambition to do things like that. I tour some, etc. But especially when we're involved in projects like this, it seems that virtually anything I can think of musically, I can see that it comes to pass. It can't really get better than that." ![]()

Golden Arm Trio and Brown Whörnet present "World Premiere Symphonies" by Graham Reynolds and Peter Stopschinski, Saturday, February 12, at 8 & 10pm. Tickets, $10, are available at 33 Degrees and Waterloo Records.