State Musician of Texas

Douglas Wayne Sahm

By Margaret Moser, Fri., Nov. 26, 1999

If Texas had such designation, Douglas Wayne Sahm would be the State Musician of Texas. Even before his death on November 18, the genial, 58-year-old musician had been making music for almost of his entire life, a Southwestern renaissance man for modern times. He was "Little Doug Sahm," playing guitar, fiddle, triple-neck steel guitar, and mandolin in country dance halls and sitting on Hank Williams' knee. He was the Sir Douglas Quintet, scoring three Top 10 hits in the late Sixties. He was Doug Saldaña, Wayne Douglas, Samm Dogg, but no matter which moniker he chose, if he stepped into the spotlight he was Doug Sahm. When he appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone in 1968, Baron Wolman's photograph of Sahm wearing a cowboy hat and long hair with young Shawn Sahm on his knee, it single-handedly created the image of the cosmic cowboy for the nation and the world. It's almost laughably quaint to explain today why the cowboy hat and long hair were such an anomaly back then, but dang if Doug Sahm, then based in San Francisco, didn't make the dread redneck look cool. The Byrds and Burrito Brothers could wear all the satin Nudie shirts they wanted; Sahm and company were the real item. The cowboy hat and long hair became his lifelong look, uniquely Texas, uniquely Doug.

If it seems odd to focus on Sahm's style of dress and choice of hats, remember that he was a native of San Antonio, and San Antonio style is like no other. The lowrider culture he grew up around valued pampered cars as much as a well-cut suit and rubbed shoulders with country boys whose idea of dressing up was a string tie and polished cowboy boots. The black show bands that Sahm admired from afar and later joined wore matching suits and did dance steps with the music. In time, these disparate influences all melded into Sahm's unique vision of Texas music, but it could have happened only in one place -- San Antonio.

San Antonio in the Fifties and Sixties was itself an anomaly, its suburban sprawl concentrated on the northern outreaches of the city -- not the south -- as if to align itself more with Austin and not with Mexico. Certainly there was little attempt to develop San Antonio's Westside, home to its Mexican population, a city within a city almost like East L.A. If you lived on the north side of San Antonio like I did, the rules were simple: You were white and middle class and you didn't cross over.

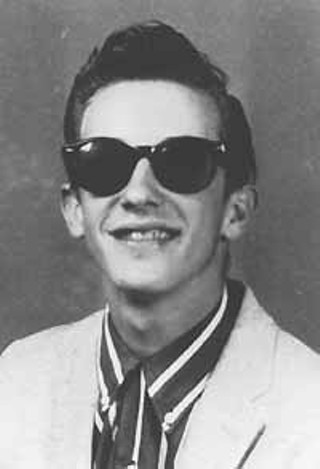

Doug didn't come from the Westside or the north side; he was from the Eastside, and he crossed every border he could. A yearbook photo reads, "Sam Houston High 1957-58," and there he is wearing sunglasses, a loud striped shirt and white jacket, and a shit-eating grin. The kid in that picture had been performing for 10 years and was about to make his second recording. Already he was hanging with Westside musicians and playing Eastside country clubs. Already he knew country, blues, Latino pop, jazz, and rock & roll. Already the Texas Tornado was being unleashed, and you can see it in that high school picture.

Doug and I were of distinctly different generations, but we had San Antonio in common. Of course it was never hard to have something in common with Doug, but there was camaraderie about being from San Antone that Doug respected. It was as if Big Red ran in his veins instead of blood, or knowing that while the rest of the world equated accordions with Lawrence Welk, under a Texas sky it was the instrument of the gods.

I didn't always understand that sort of thing, but Sahm made me understand it through his music. He went from rock & roll hero of my teenybopper years to beloved friend as an adult, but I never lost my awe of him as a musician. Whenever I could get him to play the Austin Music Awards, I did. And he did, in every configuration of Quintet and Tornados imaginable, and I was honored every time.

The last time I saw Doug Sahm was midsummer. He was in the parking lot outside Whole Foods jabbering to Derek O'Brien and attorney Jay Bell and waved me down. Did I know Virgin Records was distributing the Tornados' new LP Live from the Limo? No, I didn't. The four of us stood around under a warm Texas sun, talking, feeling fine, and enjoying the day and good company.

The old friends are the most comforting now. We look at each other and know without words that the pain of Sahm's death brings us together, a warm smile, a comforting hug, and a nudge in the ribs that yes, he's gone, but look what he left us. It's impossible to think of any one person who lived their life more fully every moment of every day.

He wrote the music of a lifetime, a unique soundtrack for the Lone Star state of mind. He left children who carry on his music in their own unique ways. He made five decades of recordings that spanned the globe. He gave millions of memories to millions of fans and played goodwill ambassador to the world with pure Texas pride. Maybe it's time to establish a state musician of Texas.

Adios, Texas Tornado. You old son of a gun. ![]()