Rosetta, My Rosetta

By Jay Hardwig, Fri., Aug. 13, 1999

|

|

It wasn't supposed to be that way -- marriages never are. The courtship of Bob and Mary Lou had been the talk of the town in tiny Pawhuska, Oklahoma, from the day in March 1939 when Bob vowed to marry "that pretty little girl with the coke-bottle figure" until the day he did so four months later. It was a storybook romance: Famous fiddler falls for local gal. But the romance faded quickly, and that same November, Bob asked for and received an annulment. Shortly thereafter, Mary Lou moved back home.

Then came Rosetta. When Bob found out that Mary Lou was pregnant, he changed his mind, and the annulment was annulled. On July 25, 1940, their daughter was born. Her name was taken from one of Bob Wills' signature songs, the Earl Hines classic "Rosetta." That night, Bob sang the song on his midnight broadcast from Tulsa's KVOO.

"Rosetta, my Rosetta,

In my heart, dear, there's no one but you.

You made my whole life a dream,

and I pray you'll make it come true."

But Bob's life -- his married life, anyway -- was no more a dream with Rosetta than without her, and by spring of the following year, his marriage was in pieces for a second time. This time it was Mary Lou's bidding -- she moved out of their Tulsa home while Bob was in Dallas for a recording session. This time it stuck. As Bob's recording of "San Antonio Rose" went gold and eventually platinum, Mary Lou moved back to Pawhuska with a $4,000 alimony settlement and $50 a month in child support. She used the money to buy a house off of Main Street, took a job at a local beauty shop, and resumed her small-town life. It would be nine years before Rosetta saw her father again.

September 2, 1950

Dear Diary,

Last night I saw my real daddy. He was so nice to me. He is wonderful no matter what my mother says. I love him. He liked me too. I played the record "Rosetta" and I had to cry. I wish my daddy and I could live by each other. I love him.

-- from Rosetta Wills' diary

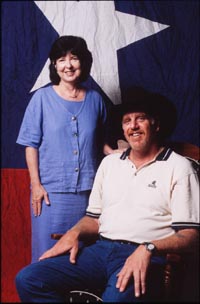

Growing up without a father is always tough, but growing up without a famous father in small town Oklahoma in the Forties and Fifties is particularly tough. Looking back, Rosetta, who lives in South Austin, says that while her daddy's absence left her confused and hurt, she didn't resent him or want anyone to speak ill of him. With her mother Mary Lou working, dating, and later remarrying, Rosetta grew up largely in the care of her grandmother Grace Belle, and Grace Belle had nothing but kind words for Bob Wills. She thought him a good, charming man. Indeed, for 50 years she kept one of his half-smoked cigars, tied with a pink ribbon and tagged "Bob's cigar -- March 27, 1939." (The same cigar now rests behind glass in the Broken Spoke's "Tourist Trap.") When Bob came to nearby Fairfax to play a gig in 1950, Grace Belle took Rosetta to meet her father for the first time.

|

|

Rosetta saw her father only twice more before she left for college. When she was 13, he dropped by the house before a local show with a new red dress for her, staying long enough to chat up Grandma and Grandpa and hear his daughter play "San Antonio Rose" on the piano. Four years later, Rosetta went to Tulsa's legendary Cain's Dance Hall to see her father perform for the first time. When a friend dragged her stageside, Bob leaned down and grasped Rosetta's hands.

"Honey how are you?" he asked kindly. "Is this your little friend? I hope you kids enjoy the dance." Then he smiled and left the stage.

After a few years at Oklahoma State, a few years in Los Angeles, and a few toes dipped into the emerging counterculture, Rosetta moved to Tulsa, which proved to be a good spot for shoring up her relationship with her dad. His cross-country tours brought him through town regularly, and for a couple of years in the early Sixties, Bob called Tulsa home. Rosetta went to all of his shows, and afterward they would sit in Wills' black Lincoln Continental and talk.

"I didn't have a close relationship in terms of time," says Rosetta now, "but when I was with him, it always felt close because he was a very warm personality. There weren't very many times, but those times were good."

It may have taken 20 years, but a father-daughter bond was starting to form. He was genuinely happy to see her; she was proud of him and curious about his life. There was a lot they didn't talk about, but at least they were talking. Father and daughter were patching things up, but Rosetta still had a couple surprises in store.

The first came when Rosetta was planning her wedding to Phil Arnett, a Tulsa native and college beau who had sparked Rosetta's interest in Ray Charles and the Bay Area beat scene. She got a call from her Aunt Olga, who told her that Betty Wills -- Bob's fifth wife and the mother of his final four children -- didn't want Rosetta to mention her in her wedding announcement.

"Oh gosh," explained Aunt Olga, "they just never got 'round to tellin' their kids about you and Robbie Jo [Bob's first child, by his first wife Edna]. Their kids don't even know he's been married before."

A few years later, Bob introduced Rosetta to her 18-year-old half-brother James at a Saturday night dance. If the sudden introduction was unnerving for Rosetta, it was even more so for James: he still didn't know he had a half-sister.

"It was awful," concedes Rosetta, shaking her head.

The revelation -- that her father hadn't told his other children about her or Robbie Jo -- made Rosetta question the sincerity of their newfound relationship. She kept her mouth shut, but inside she reeled. Ten years later, the emotions of that day came to the fore in a letter she wrote to her father.

"Why did you let me grow up without getting to know me?" read the letter. "Why didn't you tell your other children about me? You should have acknowledged me."

By the time she found the courage to send the letter, Bob had fallen gravely ill. Confined to a wheelchair, he was weak and often confused. His wife Betty thought the letter would be hard on her ailing husband, and she refused to let him read it. Shortly thereafter, he suffered a massive stroke and slipped into a coma that lasted 17 months. On May 13, 1975, Bob Wills died at the age of 70. He never knew about Rosetta's letter.

By the time she found the courage to send the letter, Bob had fallen gravely ill. Confined to a wheelchair, he was weak and often confused. His wife Betty thought the letter would be hard on her ailing husband, and she refused to let him read it. Shortly thereafter, he suffered a massive stroke and slipped into a coma that lasted 17 months. On May 13, 1975, Bob Wills died at the age of 70. He never knew about Rosetta's letter.

"I hereby give, devise, and bequeath unto my daughter, Rosetta Arnett, formerly Rosetta Wills, the sum of one dollar ($1) and my love and affection."

Bob's last will and testament was Rosetta's second surprise. Expecting to receive nothing, she got something worse: $1. Four plays on the jukebox. For a daughter who had often felt shuffled aside, the $1 bequest felt like a slap in the face. Since that time, Rosetta has learned that $1 bequests are common in wills, used to protect the estate from challenges by unnamed heirs. What's more, she doubts that her father even read the will that he signed. Still, she says with a laugh, she never got her dollar.

If the will stung at the time, now Rosetta sees it more as a funny story, an ironic exclamation point on the sporadic and sometimes strange relationship she had with her father. Her attitude is indicative of her feelings towards her dad these days: Take the good and forget about the bad. For all of his faults, Rosetta Wills truly loved her father. Besides, she says, she's not one to hold grudges.

"I think as you get older, and have children of your own, you start to figure out that most people do about the best job they can do, and hope it's right," says Rosetta matter-of-factly. She now believes her father was sincere, and that he did care about her -- even if he didn't always know how to show it.

"That doesn't mean that he did everything right, and it doesn't mean he didn't hurt me or hurt a lot of people in his life," she explains, "but there was no malice. It wasn't intentional. It was more circumstances. He certainly wasn't a devoted father by any means; his life was his music, his playing."

|

|

"It's just their lifestyle," says Rosetta, comparing her father to some of today's itinerant rock stars. "It's just what they do."

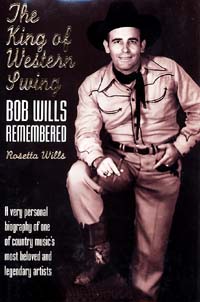

That tone, a mix of understanding, acceptance, and admiration, is plainly evident in Rosetta Wills' recent book The King of Western Swing: Bob Wills Remembered (Billboard Books, $21.95 hard). Part memoir and part biography, The King of Western Swing tells the tale of two lives, those of Bob and Rosetta Wills, and the brief moments in which they intersected. It's not a hatchet job -- not a Daddie Dearest tell-all, determined to expose her father's feet of clay.

"The last thing in the world I want to do -- because it's pointless -- is to be negative," explains Rosetta. "I want [the book] to be honest. I want it to be real. I don't want to sugarcoat it. But there's no point in the other side of it, because people loved him too much."

Besides, she adds, "I genuinely didn't feel that way. I really admire what he did, and he made me feel good."

Published last year, The King of Western Swing has been well-received, netting positive reviews and a nomination for the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award. (She was the only first-time author nominated; Fred Goodman's Mansion on the Hill won.) Rosetta, now 59, quit her job as a disabilities advocate to promote the book full time, hosting booksignings, attending awards ceremonies -- most recently her father's induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (see sidebar) -- and going to Western swing conventions to talk about her dad.

Rosetta will tell you frankly that she's enjoyed the attention that her famous father has brought her; in a way, it has made up for the attention she didn't receive when he was alive.

"Right now, I feel fine," she says about her father's role in her life. "I might not have ever written a book if it hadn't been for him. There's been a lot of great things that have come out of it. I've made a lot of new friends, had a lot of great times, and got a lot of backstage passes. It's been fun."

As for her missing inheritance, things are looking up in that regard as well. Together with Bob's other children, she recently acquired the rights to "San Antonio Rose" -- rights Bob sold to resolve an IRS dispute in the early Fifties. Dwight Yoakam sings the song on Asleep at the Wheel's second and latest tribute to the King of Western Swing, Ride With Bob, and Rosetta Wills couldn't be happier. It's a beautiful song, she says, and when the album hits the shelves, a royalty check or two should be coming her way. She'll finally make that long-awaited dollar, plus some. Long live Bob Wills.