Going for Broke

Fruit Salad Days

By Andy Langer, Fri., June 18, 1999

|

|

"We didn't know Heinz that well, but John was certainly well respected in the local community and Robert Earl Keen was a peer," says Lounge Lizard Tom Pittman. "They were wanting to become the regional version of Rounder and we saw no reason why they couldn't do it. At that moment, Rounder wasn't interested in us anyway, so it looked like a good way to go. And it was. We were good for each other."

Indeed, in those early years, Watermelon enjoyed a solid reputation for being fair with their artists. While those same artists now say Geissler quickly established a reputation for general abrasiveness and mid-conversation screaming, few have ever questioned Geissler's genuine love of Texas music, describing him as a "freaked-out music fan." In fact, where other label chiefs might not be able to list their roster, Geissler reportedly got genuinely giddy when artists such as Carla Olson would stop by the label's offices (back then, Geissler's home). At the same time, Kunz enjoyed a solid reputation as a good businessman thanks to his ownership of Waterloo Records, where he was easily accessible to artists. For his part, Keen sold his share of Watermelon to silent partner Martin Reichold of Germany in 1991 in order to concentrate on his music career.

Not only did Watermelon take chances on what may have seemed like less-than-commercially-viable artists, they also offered simple contracts, dependable accounting, and the opportunity for musicians to buy product to sell from the bandstand at a distributor price. At this point in time, Watermelon's unofficial slogan became Waterloo's: "Where the music comes first." An even more direct in-house source of pride was the slogan, "We pay royalties that other labels can't, don't, or won't."

"I always felt if you get an indie record deal and somebody doesn't give you a million bucks, the one thing you have is artistic freedom and good accounting," says Geissler. "We're honest people, and everybody knows where we live, so everybody could come all the time -- it was their back yard, not New York, Nashville, Los Angeles."

By setting up shop in Austin, Watermelon didn't have to pay the big-city rent or salaries of some its competitors. Even when the fledgling label hired several part-time employees and moved out of Geissler's home and into an office on West 24th Street in 1995, they avoided the temptation of moving into executive suites or corner offices downtown. Like the careers of so many of its artists, Watermelon always seemed to be building organically. In fact, for much of Watermelon's history, Geissler has been the only full-time employee.

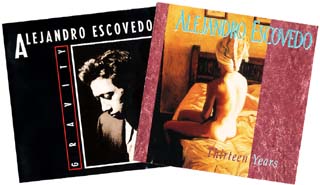

As early as 1994, Geissler's full-time job became keeping track of nearly 15 Watermelon releases a year. At that point, the Austin-based label had already established a good reputation with roots music lovers, secured overseas distribution, and seen several of its releases sell well beyond most indie standards -- notably albums from the Lounge Lizards, Tish Hinojosa, Monte Warden, and Alejandro Escovedo. Insiders cite the fact that Waterloo stepped up to the 10-15 albums a year pace while still living from one release to the next as a costly, early mistake -- even after having suffered big misses with Hamilton Pool, Steve Young, and a Timbuk 3 live album -- but today, Geissler insists that bulking up the catalog was a necessity.

"Distributors need a constant flow of product," says Geissler by way of explaining album "returns," product sold by the label to distributors that winds up failing to sell at either the wholesale (one-stop) or retail level and is sent back. Labels are responsible for buying those returns back, and without a constant flow of new product, Geissler says, distributors tend to not pay labels because they don't have the ability to offset returns with new product. "We felt like we had done everything right, and to a certain degree, having John there as an incredibly successful retailer, we always felt a lot of labels didn't pay enough attention to their retail side.

"Maybe it's not that sexy or glamorous, so for a lot of labels it's kind of, 'Who cares? The cool thing is finding the artists, hanging with them, and going in the studio.' Unfortunately, to quote John, where the rubber meets the road is when the final customer puts down $15 at the retail counter to take it home. Everything else before that is not a sale. If it goes from the distributor to the one-stop, it changes warehouses, and the one-stop still needs to sell it to a store. Then it's still only in a store. The one final sale that counts is to the customer."

The Retail Crash of '94

If there's a hard and fast lesson other indie labels can take from Watermelon's morality play, it's that the power of distribution and retail can never be overestimated. There isn't one party, from Watermelon's owners to its artists, that doesn't cite mid-Nineties retail trends as the primary cause of the label's bankruptcy. According to Kunz, the music industry's retail crunch can be traced back to 1994, when Tower Records, and later several other key retailers, demanded that they begin dealing with just one distributor per label. Up until that point, major retailers like Tower had been dealing with 10 different distributors with 10 different prices for the same product. As a result of Tower's change in policy, regional distributors began alliances and mergers that streamlined the distribution process. Before long, national independent distribution was born.

|

|

On paper, a national network of independent distributors looked like a healthy step for indie labels. Streamlined distribution promised fewer small labels getting lost in the shuffle, while the retail clout these new national alliances wielded meant indies now had access to big chain stores that were previously only major-label territory. Small labels that had always believed they could sell substantially more albums by getting their product into bigger stores now had their opportunity. Better yet, national retailers like Wal-Mart, Best Buy, Circuit City, Borders Books, and Barnes & Noble were booming, building stores as fast as they could. New stores needed product to fill their shelves, and indie distributors were more than happy to fill orders. For a year or so, indie labels like Watermelon were enjoying the largest orders they'd ever seen.

Unfortunately, a crash immediately followed the boom, when major retailers realized they were sitting on product that wasn't selling and began returning product. Best Buy, for instance, may have stocked a full line of Watermelon releases, but it was Celine Dion, not Webb Wilder, that had registers ringing. Add to this scenario the chains' realizations that they'd overbuilt, and so-called "mom 'n' pop" record stores buckling under the marketplace pressure of the larger chains, plus the 1997 bankruptcy of Alliance, one of the nation's biggest distributors, and indie labels had front-row seats to the music industry's largest retail crash in two decades. For Watermelon, this meant as many as 70,000 albums being returned to the label. Not only had Watermelon already paid to manufacture these albums, now they needed to pay for their storage as well.

By 1997, Watermelon was taking in more old product than new cash. To make matters worse, one of the label's most artist-friendly policies came back to haunt them. Whereas most standard recording contracts withhold a certain percentage of royalties to protect against product returns, Watermelon didn't. "We went ahead and said, 'If anything comes back, we'll be able to absorb it,'" explains Kunz. "We were wrong."

According to Geissler, even before Watermelon witnessed its returns grow from 10-15% to 40-50% percent, the label received another early blow when their distributor, the now defunct REP, started returning product they thought they had sold but had actually misplaced in an old warehouse.

"Their computer system wasn't what it should have been," says Geissler. "They didn't know what they had sold and what they needed to order a lot of the time. We'd get a reorder for a title because they thought they were out, and then a month later they'd go to the fifth floor of their turn-of-the-century warehouse and find 1,000 they didn't know they had."

As early as 1996, Watermelon's reputation for paying bills on time had dissolved as quickly as the returns had come back. With almost no real cash flow to speak of, invoices from manufacturers, publicists, radio promoters, and artists' publishing companies began collecting dust. A year later, the failure to pay those invoices led to bankruptcy. What could have been done about the returns? One theory is that Watermelon could have better tracked what was actually "selling through," or being bought by the consumer, by using SoundScan, the sales accounting system that drives Billboard charts. Another is that Watermelon should have cut back on its release schedule, thereby advancing less money and thus putting them in a position to pay off old debts. By now, it's a case of Monday morning quarterbacking.

"Back at that time, SoundScan was finally getting fairly well established and I think we were looking more at all the great stuff we thought we had to bring to the world and were maybe spending more on making records and getting them out than we should have been," admits Kunz. "Maybe we should have been a full-fledged subscriber to SoundScan and been looking at some of those numbers of what was selling through more. We thought we were very well connected to the street and had a good idea of what we had out there that was selling, but we were mistaken. We probably made some records that we shouldn't have and probably spent more on some records than we should have. It's a mistake that because we believed in the music and artists so much was an easy mistake to make. But until the returns came back, our indications were that it was working."

A Sinking Ship

|

|

Although Watermelon still managed to pay those artists on its roster who a) had legal representation, b) were consistent catalog sellers, and/or c) had the ability to scream louder than Geissler, it wasn't long after the retail crunch that local artists began repeating Bad Liver Mark Rubin's classic off-the-cuff line: "Friends don't let friends sign with Watermelon." By all accounts, Watermelon's failure to keep up with artist royalties, songwriters' "mechanical royalties," and even recording advances, bred a roster of unhappy artists. Although Geissler now contends that some of these disgruntled artists were simply unhappy because they were no longer being paid for records that weren't selling through, many saw Watermelon becoming the kind of label the local indie was created to fight: a label that paid its artists as infrequently as the rest of the indie world.

While Watermelon had a long history of selling product directly to its artists, eventually almost every artist that had a use for product (i.e. touring artists) began trading albums for royalties. For both Watermelon and its artists, this made sense; if the label couldn't pay cash and if the artists would have used that cash to buy product anyway, together they could cut out the middle step. And while some insiders claim Kunz used his record store to buy an inordinate amount of Watermelon product, thereby pumping some cash into his failing label, Kunz denies it. Whether or not Kunz was rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, the fact that some Watermelon artists still haven't seen mechanical royalties (a songwriter's percentage as guaranteed by the Copyright Act) or sales royalties has, not surprisingly, brought out a series of Watermelon artists who question how strong their contracts were in the first place.

"I remember telling Peter Case the particulars of my Watermelon deal once," says Alejandro Escovedo, who released his first two solo albums on the Austin indie. "He said, 'Wow! I haven't heard about a record deal like that since Muddy Waters.'"

At the same time, Escovedo is quick to admit he's never been known for his business savvy, a sentiment other unhappy Watermelon artists also repeat. While music industry experts say sketchy contracts and failure to pay royalties are not uncommon at the indie label level, at least one out-of-towner says Austin musicians may be prone to bad indie deals. According to No Depression's Grant Alden, the same apathy that drives the "Austin Curse" (high local expectations, low national sales) may drive Austin artists into record deals they eventually find undesirable.

"Could this happen anywhere? I'm not sure," says Alden. "My understanding is that status in Austin is something you acquire by playing songs for friends in a house or stage in a small bar. You don't acquire additional status proportional to the exposure you get by making records, touring, or selling a lot of records nationally. I think that's distinct to Austin and that people in Austin don't have the passionate desire to be heard in other parts of the country that people in Chapel Hill, Portland, or Minnesota would have. A lot of those people want to get out -- to get their message out and to get out themselves. People want to stay in Austin. It's a comfortable existence. And I think that breeds a kind of pensiveness in the way Austin musicians do business.

"That's what makes it easy for Watermelon or any label to continue not to pay people. It's not really what it's about for the artists. I think they seem to be happy to have their records out and happy to get some press notices, but not terribly concerned with the rest of it. There isn't the infrastructure there to be concerned, to be watching, to be monitoring the behavior of an independent label. If that were to happen in Nashville or Seattle, we'd all know about it. There are managers and lawyers and musicians there much more keenly attuned to the dynamics of business because they have to be in order to get out of the market they're in. In Austin, they're happy to be in the market and just want to be respected there."

|

|

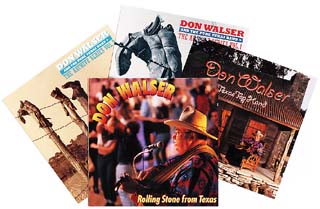

Unfortunately for Watermelon, three of the local acts whose album sales helped keep the label afloat almost singlehandedly -- Don Walser, Asylum Street Spankers, and the Austin Lounge Lizards -- were three of the indie's most unapathetic artists -- all three claiming to have severed ties with Watermelon last year. By and large, Walser's was the cleanest and easiest divorce. While Watermelon's ability to break a 65-year-old yodeler stands as one of the label's greatest accomplishments, Walser's manager, Nancy Fly, says that when the country crooner signed with Sire as part of the indie's 1997 deal with Sire, he was careful to make sure he signed with Sire, not Watermelon/Sire. Too many payments were past due to have it any other way, says Fly. For his part, Walser himself says he has no hard feelings left over from his association with Watermelon, although he still hopes some of the songwriters whose songs he covered eventually have their mechanical royalties paid.

"They did so much for so many people here and that's what's wrong with them," says Walser. "They tried to help too many people and spread themselves too thin. I was telling Heinz, it's like when I learn a song. If I really like that song but the public doesn't, then I don't sing it anymore. That's the way with signing people -- you may like them and they may be great people, but if the public don't buy them, you're wasting your money. It's just a hard fact that they had to learn."

While Walser ascribes to the popular belief that Watermelon went bankrupt because they put out too many albums, the Austin Lounge Lizards canceled their licensing agreements with the label when they couldn't get copies of their own albums. According to Lounge Lizard Tom Pittman, Watermelon was routinely late with their royalty payments, though the group opted not to sever ties with the label until after product was no longer made available to them. By mid-1997, Watermelon was so in debt to its manufacturers that getting new copies of some titles was impossible. "That's when we really got into a crossways with them," says Pittman. "Selling records on the road is a big part of our income. We're retailers on the road."

Because the Lizards' contract specifies termination of their agreement should Watermelon not fulfill their orders for product, the Lizards and their attorney, Lisa Fancher, contend Watermelon and the Lizards no longer have a deal in place. Watermelon and its lawyers say they still consider the contract valid. Similarly, Watermelon's lawyers also say they still have a licensing agreement to manufacture and distribute two albums from the Asylum Street Spankers, even though the band and their attorney, Cindy Lazzari, say they've terminated the contract. According to the Spankers' Christina Marrs, Watermelon's failure to pay royalties terminated the contract.

"We have past due royalties that they've refused to pay, and we figure if they can't be straight-up about that, we can't expect them to be straight up about anything else," says Marrs. "Now, we wonder if we're ever going to see a dime. People come up to me and ask me how to get the records and we can't get them ourselves. We have no access to them although we see them in stores. And my understanding is that they shouldn't be in stores in the first place. We tell people if they find them, go ahead and get it, but keep in mind we'll probably never see a dime. It's really frustrating to know you have a record out there that's still selling and it's money we'll never see."

Nightmares Come True

By early 1997, the complaints from Watermelon's creditors starting getting louder and more persistent. Although the success of Walser and the Derailers seemed to hint at the label's capability for breaking new artists, it wasn't hard to figure new artists don't do much good to a bankrupt label. To that end, Geissler began offering a new promise: "I'm working on a big deal and when it comes through everyone's gonna get paid." Geissler's new deal wasn't for an artist, but was instead for a distribution partner.

At the time, distribution deals cut with major labels regularly amounted to somewhere between $750,000 and $1 million in advances. Unfortunately, the deal Watermelon wound up cutting with Sire in October 1997 wasn't quite as big as Geissler hoped, netting the label only $150,000, with an additional $50,000 for the "uplift" of Don Walser and the Derailers to Sire. Along with both Austin acts went their catalogs, five of Watermelon's most successful sellers. According to Kunz and Geissler, the deal still looked like a worthy proposition because it would free them from their previous distribution contract -- a contract the label had fallen behind on by not being able to reimburse REP for returns. Watermelon believed that a new distributor would jump-start their sales flow, particularly given Sire's commitment to help promote the indie's catalog and to cut them into whatever profits were derived from new Walser and Derailers albums. Instead, most of the Sire advance went toward Watermelon buying their way out of the old distribution deal and more new albums. For the most part, Sire's advance didn't trickle down to the creditors.

Lisa Shively, a Nashville-based publicist who began working with Watermelon in 1990 on Gravity, Alejandro Escovedo's solo debut, says she was promised a portion of the Sire advance, which would pay her for nearly three years of publicity work.

"He was always up-front with me and had always paid his bills, so when he said he would pay me back when the deal went through I took him at his word," says Shively. "I got the impression he thought the deal would solve all his problems and certainly our problem. Then, when the deal came through, he gave me $5,000 and I never heard from him again."

What followed was Watermelon's first real legal tangle -- a lawsuit filed by Shively for nonpayment, and the label's subsequent countersuit alleging the publicist was incompetent. Although the countersuit was dismissed after Shively flew in No Depression's Grant Alden and Conan O'Brien booking agent Jim Pitt to testify on her behalf, the court ruled in favor of Shively, awarding her $52,000. Today, Geissler says he was too busy trying to salvage the Sire deal to spend time preparing for the Shively case and contends that rather than "incompetence," he simply felt Shively's service had suffered since his payments got less frequent and that the "bark" of their relationship had simmered to something akin to "an old married couple."

According to Shively, "Heinz changed quite a lot. When we first started working together we used to talk about music, things he found exciting, asking me what was out there. As the years went on, it was less about music and I don't even want to say business -- he just wasn't in the music part of it anymore. I don't even know if that can be reflected in his signings, but there was less time invested in each release. With Alejandro and some of the early things, we spent a lot of time.

"Then it got to where each release had maybe a month put into it. Stuff like this needs more than a month. Don Walser and the Derailers may have been exceptions, but there were a lot of records coming out that I didn't think made that much sense to put out and if you're going to put them out without any support, they're guaranteed dead on arrival. It was becoming less enjoyable for me to do it, so maybe the two of us had less to talk about, I don't know."

"Then it got to where each release had maybe a month put into it. Stuff like this needs more than a month. Don Walser and the Derailers may have been exceptions, but there were a lot of records coming out that I didn't think made that much sense to put out and if you're going to put them out without any support, they're guaranteed dead on arrival. It was becoming less enjoyable for me to do it, so maybe the two of us had less to talk about, I don't know."

Meanwhile, the Sire deal wasn't getting any better. Neither Walser nor the Derailers looked like they'd sell enough albums to send significant money back to Watermelon, plus there was a new problem on the horizon: manufacturing. According to Geissler, he and Kunz always worried about Sire's manufacturing arm, WEA, getting too busy with Madonna and R.E.M. orders to manufacture the Watermelon catalog. At the time of the deal, Geissler says Watermelon was assured fair pricing and turnaround, but what neither label anticipated were manufacturing issues that resulted in a major redesign of each Watermelon order.

Geissler explains that Watermelon's bar code configuration was one dash and one digit off from the WEA system's standards and that the label film (the art for the actual CD surface) was two millimeters too large for WEA's CDs. As a result, each Watermelon CD inlay had to be redesigned prior to ordering. Geissler claims Sire would then take 10-12 weeks to manufacture jobs Watermelon's old manufacturing outfit would take two days to complete.

"Our worst nightmare had come true," says Geissler, who points out that each hiccup in the manufacturing process was slowed down by a communication process that filtered between the pressing plant, Elektra, Sire, and then back to Watermelon. "But WEA has been doing business so long they weren't about to change their ways for Heinz and John. We walked into it knowing some of these problems could occur, but when all of them did we were shocked."

Geissler says he also knew that Watermelon and Sire had failed to come to an agreement on a return reserve rate, the percentage of sales held by the major until product sold through, returned later to the indie in a lump sum. Although the reserve rate wound up being set at an industry standard of roughly 20% instead of something more favorable, Geissler says he thought Watermelon could make the advance last until that reserve rate was returned to the label in late 1998. According to Kunz, just as Watermelon was about to receive its reserve withholdings, Sire stopped offering timely accounting and sales reports. Sire would not comment in detail for this story, but Watermelon cites that lack of accounting for their final push toward bankruptcy.

Not for Sale

In the months preceding Watermelon's declaration of bankruptcy, the label entertained two bailout efforts and filed one piece of paperwork that wound up a public relations nightmare and further distanced Watermelon from its roster of artists. That document, a UCC-1 financing statement filed with the secretary of state's office, offered 63 masters, contracts, and licensing agreements to Sire as collateral on the advance Sire paid almost a year earlier. Although the filing was requested by Sire and should have been made at the time of the advance, the document had the appearance of Watermelon voluntarily handing over the rights to their artists' livelihoods. That Watermelon was so clearly insolvent at the time of the filing made the label look even worse.

In truth, the origin of this "smoking gun" document is much less alarming than it appears on the surface. Advances are recoupable loans, meaning the only thing a recording label or act has to offer as collateral are its masters, contracts, and licenses. In effect, turning in a list of those holdings to the secretary of state's office only "perfects" a loan agreement the same way a title does on a car loan: If you were to default on a car loan, the bank holding the title can then pick up the car itself. Nonetheless, the UCC-1 filing made it look like Watermelon was more than willing to sell its artists over to Sire, a label none of them had originally agreed to sign with. Although Watermelon and its attorney, David Ward, say they've heard similar concerns from Watermelon artists, Kunz says nothing so sinister took place.

"It wasn't anything to sell them down the river," he says. "We were in a situation where if we had gone to the bank to borrow money, the assets we would have had were the masters we owned. Although Texas banks don't seem to understand that, Nashville, New York, and L.A. do. We could have maybe had the same scenario with somebody saying, 'Wait, Bank ABC owns our masters?' When you go somewhere and essentially get a loan you have to put up collateral. It's that simple."

Less simple were Watermelon's last-ditch efforts to restructure their deal with Sire. Sometime after May 1998, Geissler and Sire president Seymour Stein reportedly came to an agreement for a restructured deal that promised better accounting, better manufacturing turnaround, and more attention for Watermelon's developing artists. According to Geissler, his and Stein's handshake phone agreement was rejected by Warner Music Group brass hours before it was designed to go into effect. "That's where the shit hit the fan," says Geissler.

Less simple were Watermelon's last-ditch efforts to restructure their deal with Sire. Sometime after May 1998, Geissler and Sire president Seymour Stein reportedly came to an agreement for a restructured deal that promised better accounting, better manufacturing turnaround, and more attention for Watermelon's developing artists. According to Geissler, his and Stein's handshake phone agreement was rejected by Warner Music Group brass hours before it was designed to go into effect. "That's where the shit hit the fan," says Geissler.

Another deal, this time with Warner Bros. vice-president of publicity, Bill Bentley, also failed to come together before Watermelon's bankruptcy. Bentley, an Austin expatriate with strong ties to local music, began negotiating with Kunz, and later Geissler, last fall. Although the deal never got to the serious negotiation stage, Bentley saying he was never provided enough information, the L.A.-based music industry veteran says he talked with Kunz on at least 10 occasions about a possible purchase.

"At one point, John called back and said, 'It's not for sale,' and that Heinz was going for reorganization, and therefore he's going to keep the label," explains Bentley. "I think we both realized that if I bought it, I was going to work there and Heinz wasn't. There wasn't room for two heads of the label. That's nothing negative about Heinz. It just couldn't support the payroll and had to be an either/or deal."

Did Geissler refuse to entertain the idea of selling the label if it meant stepping aside, thereby putting himself ahead of the label's best interests by opting for bankruptcy instead? Both Kunz and Geissler deny the deal ever got close enough for a decision to be made. And while the brunt of the blame for Watermelon's bankruptcy has fallen squarely on Geissler's shoulders, some Watermelon artists have also begun questioning Kunz's role in the label's pre-bankruptcy, day-to-day decision making. Was Kunz merely a silent partner?

"I don't think I've ever been a silent partner," says Kunz. "Heinz and I spoke, and still speak, several times a day. As far as the day-to-day operations of the business, that was Heinz's realm, and if something was out of the ordinary or a problem came to my attention, we talked about it. There were certainly times when something would come to my attention from the artists' side rather than Watermelon and I'd go check into it. In some cases, there was a valid complaint and in some cases there wasn't.

"I was trying to do what could be done for the label all along. The last couple of years we had some hard and tough business decisions to make. When the big tough decisions needed to be made, Heinz and I would get together and make those. I wish, and I know Heinz wishes, we weren't in this situation. It's nothing that any business person would want -- to be in a situation where one has to completely reorganize the business to make it still viable. We believe we have a company where it's worth doing that for.

"It certainly would have been easier to throw in the towel and say we're going to liquidate the business. Part of that is that we've been building and fighting for this company for a long time -- fighting for the artists and the music we're trying to bring to the world. But tough decisions had to be made, and sometimes they're not the decisions you'd make in a kinder and gentler world."

Pounds of Paperwork

Both Geissler and Kunz attest to the fact that their decision to file for bankruptcy was not made in a kinder, gentler world. Although Geissler told the Trustees' Office he first considered bankruptcy last October, Watermelon wound up officially declaring Chapter 11 on the last day of 1998. As complicated as Picture #1 had become -- everything leading up to their filing for bankruptcy -- Picture #2 didn't seem to promise any kind of elementary fix either. In fact, as a debtor hoping to find someone to help reorganize their company and cover their debt, the only thing Watermelon did quickly was become an open book. By and large, the label's debts, financing, and day-to-day business affairs became public record.

With little or no operating income at the time of bankruptcy, Watermelon went from an operating label to pounds of paperwork almost overnight. At the same time, Geissler reduced his staff and moved Watermelon's offices back to his home, he and attorney David Ward busy preparing the Trustees' Office most basic mandate: a statement of financial affairs. Among the revelations in those documents, which were initially filed January 15 and then amended on February 25, were the following:

• Watermelon's cash collections dipped from $616,488.37 in 1996 to $199,977.44 in 1998. In 1997, the year most indie labels felt the brunt of the retail crash, Watermelon collected just $267,659.14 -- less than half of the previous year's take.

• Watermelon's Chase Bank account for just over $8,000 had been seized by the Press Network, publicist Lisa Shively's company.

• Watermelon may have amassed as much as $1 million in debt, where at least 20 creditors are owed more than $1,000 each. In addition to what is owed publishing giants The Harry Fox Agency ($200,000) and Warner-Chapel Music (unspecified), some of the largest disclosed creditors include: manufacturer Disctronics ($60,894), publicist Cathy Halgus ($3,822), office supplier Pitney Bowes ($10,732), Kathy Marcus Design ($5,225), Dick Reeves Design ($1,741), and radio promoter Al Moss ($3,650). Not discounting Sire's $100,000 claim and Shively's $52,000, Watermelon's debts range from a $50 tab due to the Austin Police Department's Alarm Unit for a false security alarm to the scariest of all creditors, the Internal Revenue Service ($7,000).

• In 1998, Geissler received a salary of $28,000, while Kunz went unpaid.

• A disclosure of royalties due to artists illustrates just how far behind Watermelon had fallen in paying both artist royalties and mechanical royalties to uncontrolled songwriters (songwriters not in the recording bands themselves). Among the artist royalty debts: the Asylum Street Spankers ($4,129.23), High Noon ($3,305), Tish Hinojosa ($4,807), the Silos ($2,651), and Don Walser ($8,226). On the mechanical royalties side, Watermelon owed an additional $18,402 for Webb Wilder albums and $25,455 for Walser recordings.

To complicate matters, those figures do not include albums sold after June 1998 because Watermelon claims they only received updated sales accounting from Sire last month. In addition to the filings, Geissler and Ward have had to attend two more creditor's meetings, mini-depositions where legal representatives of the creditors can question the debtor in hopes of clarifying the finer points of the public records and reorganization plans. At those meetings, lawyers for the creditors learned:

• At the height of Watermelon's weakest financial period, March 1998, the label advanced nearly $15,000 to Johnny Bush for recording a new Watermelon album.

• Geissler considered Carla Olson "The Queen of the Cut-out Bin" and estimated neither her releases nor the much-celebrated Austin Nights collection sold more than 2,000 units total.

• Geissler maintains that Watermelon doesn't recognize the revocation of contracts by the Austin Lounge Lizards nor the Asylum Street Spankers.

• Under the Sire deal, Watermelon was supposed to receive checks monthly, but only 23% of total sales were to be returned to the indie. In addition, the 20% held for returns was scheduled for repayment every nine months. Watermelon contends they had received no accounting or checks from Sire since the initial advance was paid.

This last point, Sire's alleged failure to account to Watermelon, has been a bone of contention for both Watermelon and its creditors since the beginning of the bankruptcy hearings. Although Sire's attorney, New York-based bankruptcy lawyer Brian Herman, says that any claim Sire hasn't been forthcoming is "inaccurate" and that Sire is now "up-to-date," the lack of overall sales accounting seems to have had a trickle-down effect on Watermelon: Without sales figures, artists don't know what royalties they're owed, and therefore how much say they have in a reorganization plan.

"Most of my artists haven't been accounted to," says Cindy Lazzari, who represents 27 separate entities in the Watermelon case, including Iain Matthews, the Asylum Street Spankers, Monte Warden, and the Derailers. "To know our powers and rights, and our position in the bankruptcy, we have to know what portion of Watermelon's debt we represent."

It's All in the Planning

A prime component of Chapter 11 is the idea that those parties owed money by the debtor have a vested interest in the financial future of the party that filed for bankruptcy. It's therefore a committee of creditors who vote on a reorganization plan that best serves both the company and the creditors. When all of Watermelon's creditors are taken together, none is more important than Sire Records; their position in the negotiations cannot be underestimated. Not only do they have a security interest in all of Watermelon's assets, they also have the only debt that must be paid outright -- what is referred to in bankruptcy law as a "secure" debt. Although the fact that the security agreement was filed within 90 days of Watermelon's declaration of bankruptcy may leave the Trustees Office capable of voiding that agreement, nobody is denying Sire will be a key player in any reorganization effort.

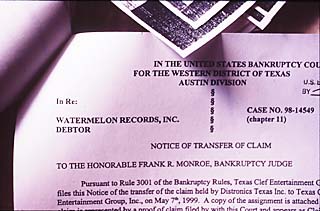

The first reorganization plan presented to the court, a filing from a company called Texas Clef, leaves little question that unless the court rejects Sire's claim on the master tapes and licenses, there would be no assets to distribute, and therefore no possibility of a deal. If Sire's claim were removed, Texas Clef has promised to pay $83,000 to reorganize Watermelon. Who is Texas Clef? According to court documents, Texas Clef is led by Antone's Records CEO Randy Clendennen, although Clendennen and his attorneys are quick to point out that Antone's and Texas Clef are two separate entities. The importance of this point is clear: Antone's Records has its own distribution deal with Sire Records, and at least in theory, to pull the rug out from Sire on the Watermelon deal would not be good for Antone's own relationship with the major label. Clendennen says he's not worried about alienating Sire.

"I can see how it may look odd, but this has nothing to do with Antone's," says Clendennen, who believes any reorganization plan would have to nullify Sire's lien. "I don't think we alienate Sire or that we have targeted Sire."

Although Texas Clef's plan was filed only after negotiations with Watermelon stalled, Clendennen won't say whether the fact that his proposal isn't the indie's officially submitted plan means Geissler himself would not fit into the Austin label's future. Clendennen hints that Geissler might stay, but Clendennen's attorney, William Davidson, is less committal.

"It doesn't involve Heinz," says Davidson. "We have proposed to purchase some of the assets and move forward with or without him. The two aren't related. The purchases by Texas Clef isn't conditioned on a relationship with any of the current owners of the corporation. It's possible we'd keep him and possible they wouldn't. There's been no decision one way or another."

For the artists involved, the big question is how Texas Clef intends to address the issues surrounding Watermelon's debts, as well as their own contracts and master recordings. As part of the plan, Texas Clef intends to continue working with 39 different Watermelon artists. To do so, says Davidson, they would have to honor the artists' contracts with Watermelon and "cure" any defaults in the contracts -- make arrangements to pay their debts, if not in full, at some agreed upon percentage.

Although Watermelon's officially sanctioned plan had yet to be filed at press time, Geissler, Watermelon attorney David Ward, and Jeff Skillen of Valley Entertainment, a California-based company presenting the reorganization, promise their plan would pay the artists in full. Valley Entertainment's proposal includes working out a settlement with Sire prior to filing, thereby not having to ask the court to declare Sire's advance "unsecured." At press time, Sire and Valley had reportedly reached a handshake agreement. Valley says they would keep Geissler in charge of operations and keep Kunz on as a consultant, although it's as yet unknown whether either would enjoy any equity in Valley's version of Watermelon.

Who is Valley Entertainment? According to Skillen, his group is the in-house record label division of Valley Media, one of the country's largest one-stop wholesalers, which owns Distribution North America, the largest independent distributor in America, servicer of close to 90% of all Internet-based CD sales. What has raised eyebrows about Valley Entertainment's interest in Watermelon is that not only do they have the deep pockets it would take to pay the artists' contracts in full and the leverage to negotiate directly with Sire, they also own a proven distribution system of their own. In addition, by operating DNA, they own the company most artists would eventually be selling through if they were given the chance to buy their masters back in a liquidation.

Tish Hinojosa, for example, would likely license the rights to her old recordings to Rounder (her current label), who would then distribute them through their deal with DNA. Such a scenario might leave Hinojosa and other Watermelon artists in a position where voting for the Valley Entertainment deal makes more sense than rejecting it; if their albums are going to be distributed by DNA anyway, why not be part of Valley Entertainment's operations directly and have their sales force enjoy an incentive to move her product?

If both the Texas Clef and Valley Entertainment plans sound confusing, it's because they are. It's expected that Texas Clef will refile their plan with more specifics and that the initial Valley Entertainment filing should disclose the details of their deal with Sire, but lawyers for the artists say the good news is already that both plans take steps toward addressing the artists' concerns -- even if it's out of legal necessity.

Filing Frustrations

Even as representatives for Texas Clef and Valley Entertainment work on making deals for reducing debts and securing voters behind the scenes, Ward is guessing Watermelon's restructuring is probably still three to six months away. What few involved with the bankruptcy want to speculate about are the ramifications of liquidation. In the event neither restructuring plan is approved by creditors, the court could turn Watermelon's Chapter 11 into a Chapter 7, allowing artists and outsiders alike to bid on purchasing Watermelon's master recordings and remaining inventory. For the artists, the good news is that they might stand a chance at getting their masters back. If that were the case, artists could then take those masters to another label or manufacturer and release them on their own. At least one local attorney is advising that Watermelon artists, whether they met the deadline to file an official claim or not, "file for notice" with the bankruptcy court so they're kept in the loop about news on a potential liquidation.

"Whoever is in charge of the liquidation, the debtor or the trustee, is supposed to give notice to everybody before selling rights or product," says the Lounge Lizards' attorney, Lisa Fancher. "That's a pretty good opportunity for artists to come in and buy them for dimes on a dollar. The main obstacle is that artists get these piles of paper and don't know what they mean or don't read the fine print. It's a good time for people to pay attention to what they get in the mail."

Although several Watermelon artists interviewed for his story admit they initially hoped for liquidation and the chance to buy their masters, most admit they'd just like to see their albums stay in print, which is why they may have signed with Watermelon in the first place. Monte Warden, who recorded two albums for the label, says that while he and Geissler have a longstanding disagreement over his product debt and Watermelon's unpaid royalties, the country singer says that having a new Asylum album on the charts means it's disappointing not having his old back catalog available to get a boost.

"Now would be a great time to get my masters back," says Warden. "Pie-in-the-sky, I assign them to Asylum. Either way, Heinz ought to be happier than a pig in poop that I'm on a major label. But pile-on and cheap shots are not my game. Does the guy owe me money? Yeah. Did he probably get screwed somewhere along the way? Yeah. But why would he want to take that screwing out on the people that made records for him? Maybe he doesn't. Maybe he's just back in the corner. All I know is that after the time I took off for my son and I was ready to make records again, the only two guys that let me be my own A&R department were Heinz Geissler and John Kunz. Everybody else had strings attached."

From Warden on down, the backlash from the Watermelon artists hasn't been as strongly worded as the backlash from their lawyers, whose job it is to play hardball. According to several lawyers pursuing claims, the label's bankruptcy comes down to one thing: blatant breaches of contract. Although both reorganization plans promise to remedy the artists' claims, at least one attorney says that shouldn't take precedence over the fact that it's the artists who have done the least to deserve a prolonged bankruptcy.

"I don't second-guess Heinz's business acumen because the recording business is inherently high-risk and complex," says Cindy Lazzari. "But I can tell you that it's most unfortunate for the artists. What needs to be remembered is that Heinz has already collected the money that my clients are owed. It's not like it's a spec deal. He's collected this money and not paid it. We're only asking for money he already collected. To force artists to spend more time and money chasing and protecting their interests after he's collected their money and not given it to them adds insult to injury."

Within the ranks of artists and attorneys following the Watermelon bankruptcy there are also those who wonder whether Geissler should be involved with any potential future version of Watermelon. Would the Texas Clef plan have a better chance with creditors if Geissler were out of the picture? Perhaps. If Geissler claims he's learned a lesson from Watermelon's bankruptcy and pledges a new policy of fiscal responsibility, can he change some minds? Again, perhaps. The only sure thing may be that this morality play doesn't have far to look for its tragic hero. Is Geissler not the archetypal music fan that loved music too much?

"[The bankruptcy] has been a big-time frustration," says Geissler. "I also personally think it's sad that sitting in the hot seat can put you at odds with artists you considered friends. When a record doesn't sell the way we all hoped, the label gets blamed. Ultimately, the consumer makes the final decision. We can only produce the tools and get music to the consumer. Unfortunately, I can't stand in front of a record store with a gun in my hand and force people to buy Watermelon records."

Maybe not, but according to Geissler, to have owned a record label that put him in a position to sell the records he loved, there have been as may rewarding moments as "big-time frustrations." But while the label Geissler and Kunz founded sits in the midst of bankruptcy, the real question is simple: Were the six years of prosperity and goodwill worth that final four that led to hard feeling and bankruptcy? Is it any surprise there isn't a simple answer?

"For me, I'd like to see Watermelon as a label survive and thrive," concludes Geissler, "with the records in print and viable. That's what I'd like to see. I'd like to see the creditors be made as whole as they possible can and the artists feel like they got the best deal they possibly could. That's an important part of the label being able to move forward.

"Was it all worth the headache?" asks Kunz. "Were the first six worth the last four? I learned an awful lot of things I never wanted to learn -- bankruptcy being the biggest of them. But I think it depends on how everything shakes out. If it shakes out the way I just said, with these objectives being attained, then probably, yes. Although it was a hell of a bumpy ride."