Hill Country Breakdown

By Christopher Hess, Fri., June 4, 1999

|

|

Guitar, banjo, upright bass, fiddle, and mandolin moved in smooth synchronization around the single condenser microphone, instruments held upward for amplification, the musicians trading solos and filling in between verses, a dance greeted by whoops from some and quiet dismay from others. Naturally, it was only a matter of time before the inevitable shouts for the former outlaw's theme song, "Copperhead Road," began -- standard meathead procedure at any Steve Earle show. They were politely absorbed and disregarded. There would be no rock & roll reprieves on this night, no flashing of the old Earle muscle that his fans have come to expect. This was, in Earle's own words, a bluegrass show.

In truth, the real bluegrass started when Del McCoury himself, the venerable, silver-haired guitar picker and patriarch of contemporary bluegrass music, came out and joined the proceedings. The first set moved along smoothly, Earle's deep nasal vocals breezing through the choreographed movements of McCoury's band -- made up largely of the elder's sons -- as they alternated solos and harmonies. It was only after Earle left the stage, however, that the energy level jumped perceptibly. With the Del McCoury Band center stage, the tempo nearly doubled, breakneck gallops through "The Look of a Perfect Diamond" and "Red Eyes on a Mad Dog" warming the crowd considerably. Though Earle's effort was a good one, with some of the tunes for his latest release, The Mountain, almost sounding like old bluegrass standards, it was obvious that this music was not, at this point anyway, his life's pursuit -- not the way it has been for the McCoury clan for many decades. Theirs was a different language.

"I wish I were as sure about anything as Bill Monroe was about everything," writes Earle in the liner notes to The Mountain. He goes on to account for his introduction to and continued fascination with bluegrass music, declaring the intention for his first acknowledged attempt at making a bluegrass record: "I wanted to write just one song that would be performed by at least one band at every bluegrass festival in the world long after I have followed Mr. Bill out of this world."

Despite the fact that Earle has not yet succeeded at his lofty goal, there's one thing he was right about: Bill Monroe single-handedly invented an American art form. Everyone who plays bluegrass or studies bluegrass or voraciously consumes bluegrass music agrees on that fact -- and that's about the only thing they agree on.

"There's this dichotomy, and it's been going on for at least 20 years," says Eddie Collins, leader of local bluegrass outfit the High Stakes Rollers. "There's a society for the preservation of bluegrass music, and they're real traditional. They want to define bluegrass music as Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs of 1950, and their favorite bands all play music like that, fitting into a definable music form. Whereas most folks, even Bill Monroe and the great players themselves, see it as an emerging music form that's always gonna grow and always needs those who are gonna push the edge."

Collins, who teaches banjo and guitar at South Austin Music, is an active member of the Central Texas Bluegrass Association, a regular participant in the bluegrass jams at Artz Rib House -- one of the few steadfast bluegrass venues in Austin -- and winner of second place in this year's Texas State Banjo Championships. While he's an active and visible proponent of bluegrass, he takes a more pragmatic view of devoting one's life to anything so specifically defined. His most recent album, Guitar Slingers & Texas Music, is Western swing, country blues, and singer-songwriter material. While all these root forms are linked to bluegrass historically and stylistically, there are a great many music fans for whom never the twain shall meet.

Whether pursuing related genres of music or "pushing the edges," there are vast and organized numbers who feel that the thing called bluegrass should, quite simply, be left alone. While this unyielding devotion to tradition may seem extreme to some, it's this same attitude that has allowed the music to remain, in a widespread sense, the same as it ever was. In Central Texas, few embody this preservationist spirit as fully as Temple's Leon Valley Bluegrass, who've been playing it straight since 1977.

"I think bluegrass has a stability that most musics don't have," says Ernest "Hoss" King, mandolin player for Leon Valley Bluegrass. "Since Mr. Monroe started it back in the Thirties, it's followed a traditional pattern. That's where we're at. We're probably more traditional than most bluegrass bands, because we have tried to keep with the traditional standard he started back in the Thirties and Forties."

There's a multitude of bands throughout Central Texas that have stayed true to traditional bluegrass: WST Bluegrass (We Sorta Tried), Grazmatics, HTML (Hard to Make a Living), and the Manchaca All-Stars, just to name a few. Artz Rib House, Green Mesquite, and the Manchaca Volunteer Fire Department are weekly hosts of the music, which can also be found, occasionally -- in some form -- at the Cactus Cafe and Flipnotics Coffee Space. For the most part, though, as has been true for many years, bluegrass music lives mainly at community jams and summer festivals. In the southeast United States, where the music was born and bred, there's a festival almost every weekend, most composed of nothing but bluegrass bands. In Texas, besides the fact that the bluegrass itself is a bit different, having been heavily influenced by the Texas fiddle tradition, the festivals are often not exclusively bluegrass.

The CTBA's annual festival in Zilker Park, for instance, has remained mostly bluegrass, although seminal Austin band the Bad Livers headlined last year -- a band that is not, despite many claims to the contrary, a bluegrass band. There are also bluegrass festivals in Spring Town, Texarkana, Canton, and many more towns throughout Central Texas during the summer months (check the CTBA Web site at http://www.jump.net~ctba). North of Austin, there's the Old Settler's Music Festival in Round Rock. Formerly called the Old Settler's Bluegrass & Acoustic Music Festival, over the past several years the bluegrass has been increasingly replaced by what co-producer Randy Collier calls the "Austin sound" -- any combination of singer-songwriter, folk, blues, rock, and country. Headliners this year were Patty Griffin and Joe Ely. Not bluegrass.

"It was more bluegrass before," says Collier, "and in my heart, I wish it could be all bluegrass. But it doesn't sell. A straight bluegrass festival does not sell tickets here. It's not because it isn't a good form of music, but because not enough people have heard it.

"[Besides] I think there's enough room in Bill Monroe's vision to include a lot more than just that. That was his style, but he also wrote a lot of tunes that covered a lot of ground. 'Blue Moon of Kentucky' was an Elvis hit. He has a lot of instrumental songs that are pretty jazzy, that use more than just three chords."

The grounds of Old Settler's park are awfully big for an audience comprised solely of bluegrass fans, as many people in the community understand. The festival's attendance was down from last year, when the lineup was more bluegrass than this year. While he understands the motives behind the diversification of many bluegrass festivals, LVB's Hoss King points out a possible reason that festivals suffer for it.

"I can't fault people who try to do that," he says. "However, bluegrass folks are a hard-core bunch of people who are just not satisfied if it's not bluegrass. Most people who are in the bluegrass arena, if they're going to a bluegrass festival that's what they expect to hear and see. And if it's not bluegrass, they're disappointed and often will not go back. They can be kind of callused. Most of them want traditional bluegrass. There are a lot of variations in bluegrass, but as long as it maintains that bluegrass sound most people will accept it."

Though bluegrass music sounds as if it's older than the hills themselves, the fact is that it originated fairly recently, in the early Forties, through the music of Bill Monroe and his band, the Blue Grass Boys. The instrumentation of the band went through several changes, incorporating many stringed instruments and even the rare accordion or horn, but eventually, sometime around 1945, a definitive lineup was established -- a model accepted by staunch bluegrassers as the only truly acceptable instrumentation from that time on. The group's namesake played mandolin, and Monroe is generally credited with linking the instrument to country music. An upright string bass filled out the bottom, and a flat-picked guitar set the rhythm. Solo duties were handled by mandolin, fiddle, and banjo, with the occasional dobro thrown into the mix -- though some regard even that with suspicion.

Bluegrass was not an entirely new or revolutionary form of music, but rather an evolution of country music into a highly technical style related to old-time music, country blues, and string bands, created at the hands of Monroe's landmark ensemble. In addition to the instrumentation, bluegrass is characterized by a distinct style of singing and drastically increased tempos. Vocals dwell in the upper reaches, and it's this high-pitched, nasal, straight-toned style that creates the so-called "high lonesome" sound that is the hallmark of bluegrass.

The event that cemented the bluegrass sound and format came in 1945 when Earl Scruggs joined Monroe's band as its five-string banjo player. Scruggs' three-fingered picking style was revolutionary, taking an instrument that had all but disappeared from the forefront of country music and making it the centerpiece of a cutting edge band in a highly virtuostic playing style. "Dueling Banjos," "Foggy Mountain Breakdown," and the theme to The Beverly Hillbillies are all defined by Scruggs' instantly recognizable sped-up string-picking that drives like a train.

This innovation in music captured the hearts and imaginations of countless musicians and music fans. The bar had been raised, a new standard had been set. In the same way that Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker changed the sound of jazz -- at approximately the same time, in fact -- Bill Monroe's Blue Grass Boys took country music to new levels of instrumental competency, making nothing short of virtuosity acceptable. The Stanley Brothers, Flatt & Scruggs, Reno & Smiley, the Osborne Brothers, the Dillards, Jim & Jesse were all imitators of Monroe's, each act adding its own twist (two fiddles, a dobro) to make themselves unique. Common to all of them was the dizzying capacity for instrumental solos that is essential to bluegrass.

Recent Austin performances by Bela Fleck & the Flecktones and David Grisman demonstrate where cultivating total mastery of an instrument can take a player. Both nationally renowned musicians are former practitioners of bluegrass, but while few would argue that Fleck's banjo playing or Grisman's mandolin work are near the top of their respective class in the world, likewise, few who know would consider calling the music created by either of them bluegrass. They have abandoned traditional group instrumentations as well as standard repertoires to pursue their instrumental capabilities outside the genre.

These career moves have gained both Fleck and Grisman large fanbases, mostly among the displaced Deadhead contingent, linking them to the swelling movement of mutant bluegrass bands -- "MuGrass" -- like Leftover Salmon or String Cheese Incident. Both have also gained commercial success far beyond nearly anything in the world of bluegrass. Not surprisingly, it hasn't endeared them to the traditional community. The term "soulless technician" often comes up in reference to both of them, and for those who have dedicated themselves to the music of Monroe, their music is generally nothing but gymnastics. Lack of soul does not bode well in a music so steeped in the gospel, and their jazz-infused extended jams are anything but traditional.

Buck Buchanan, guitar and dobro player for the Manchaca All-Stars, who play the all-you-can-eat fish fry at the Manchaca Volunteer Fire Department the second Friday of every month, is a bluegrass traditionalist by upbringing.

"I grew up with it," he explains. "When I was six years old we got our first battery radio in the hills of Tennessee, and from there on it was the Grand Ole Opry every Saturday night. Bill Monroe and the Stanley Brothers and Flatt & Scruggs, after they left Bill Monroe's group. I think Flatt & Scruggs were my favorite band of all time. They were a lot more versatile, they did some of the slower tunes and proved to the world that you didn't have to play bluegrass at 90 miles an hour. And they added the dobro to bluegrass."

Buchanan's opinion of the tendency toward commercialization of bluegrass is tolerant, even understanding. Change is inevitable, that's just the way it goes. That doesn't mean he takes part, though.

"I watched this happen back in the Forties, and now it's starting all over again," he says, laughing. "Everybody's saying, 'I gotta pick-up my guitar. I'm not able to hear anything,' and then when everybody's electric again there'll be a few hard-core bluegrassers around that want to do it the old way. Then in another 10-20 years, we'll be back to the acoustics again. When the 40-year-old guys get to be 60, they all go back to their roots."

The All-Stars have seen approximately 200 players pass through their ranks since they started in 1978, and the group's repertoire has remained traditional bluegrass the entire time. And as far as expanding the genre's canon and contributing new material or twists on the form goes, it doesn't much matter.

"I've written a couple songs, my brother [Ben, All-Stars' guitarist/vocalist] has written four or five. I've never been much on wanting to write new songs -- there's so doggone many good ones I haven't learned, you know? I never felt the need for it. That's what sells is the new stuff. But, like I said, I never wanted to sell it. I just do it for enjoyment."

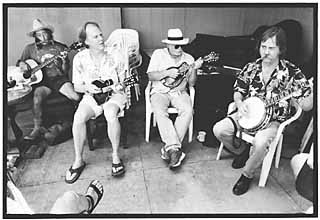

The appeal of the music to Buchanan has always been, and will always be, of the most fundamental sort: "A bunch of guys can get together under a tree and not have to have a lot of electronic equipment to play music. Just sit down and enjoy themselves. I think jammin' is the most enjoyable part of it."

It's precisely such spirit that has kept bluegrass alive and well in this country and beyond. Recently, guitar great Peter Rowan played the Cactus Cafe with Druha Trava, a bluegrass band from the Czech Republic. There are Japanese bluegrass bands as well as Norwegian bluegrass bands. The music is about community, about working toward the mastery of an instrument, and anywhere those things are brought together and appreciated, there's bound to be a bluegrass jam going on, regardless of commercial reception. Mark Rubin, bass and tuba player for Bad Livers, has this advice:

"Anyone who sets off on that path has to be aware of the fact that there is only a certain amount of economic recompense. The people I know who are the happiest at this stuff do it as part of a familial tradition, or a cultural tradition. That's where it's rewarding."

According to Rubin, unreasonable expectations are what lead many practitioners to fret at the state of bluegrass in today's popular music market.

"The bluegrass music industry is in a state of operative denial," states Rubin. "The operative denial that's in place is that bluegrass is a commercial music. The fact of the matter is it's not. It hasn't been since the mid-Sixties when Flatt & Scruggs stopped having hits with Bob Dylan covers. Like many musics that are based in traditional forms, at one time it was a commercial entity."

When contemporary artists discover these old forms of music and are so inspired by them that they attempt to copy or revive them, the resurgence of artistic interest, combined with the lack of a commercial interest, brings the music into the realm of the folkloric. For example, bluegrass is a folkloric art, while swing jazz is not. With respect to bluegrass, many of the form's originators and first wave of practitioners are still around, offering tips and wisdom to those looking to keep the music alive. But, with bluegrass, it doesn't come easy.

"Bluegrass music requires the study of a lifetime," says Rubin. "That's the problem. You end up trying to commercialize all this effort and you run into a brick wall. So, within the bluegrass music scene is the attempt to somehow improve bluegrass -- the catch phrases are 'Expand its horizons' or 'Push the tradition.' A friend of mine calls that rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

"I think that's exceptionally misguided, because you have to be awake with the modern age and understand that once you're in the study of bluegrass music it's akin to the Civil War recreation or the Society for Creative Anachronism. It's only going to be a hobby. Tom Ludwick and [Leon Valley Bluegrass] epitomize what bluegrass music is today. They are people who are music fans who got turned on to this particular art form and then devoted themselves to it as an all-consuming hobby, which then becomes a lifestyle."

|

|

Rubin's own band, Bad Livers, is often referred to as a bluegrass band, a title Rubin and bandmate Danny Barnes -- a banjo player and guitarist of extraordinary skill -- flat-out deny. "I have far too much love and respect and admiration for bluegrass to have ever chipped away at its reputation by assigning our dumb asses to it," says Rubin.

Rather, both Rubin and Barnes were well-versed in bluegrass and went on to develop their own style of music, which was based as much in the ethos of punk rock as it was in the style or instrumentation of bluegrass. While it's tempting to relate banjo music to bluegrass as a means of discussing the music of Bad Livers, the weight and focus carried by the bluegrass tradition makes its title something to be taken more seriously than a word like, say, "rock."

"It's like the word 'folk,'" continues Rubin. "Folk now includes these pathetic singer-songwriters telling you all about their girlfriend. The whole detestable singer-songwriter phenomenon now goes under the moniker 'folk.' I think Big Bill Broonzy is a folk artist, not this stuff. Just because the whole situation today is jive doesn't mean the terminology has to follow it too."

Though his musical partner Danny Barnes has a more positive outlook on the general state of music -- the phrase "Music is good" comes up often in his speech and on his Web site (http://www.dannybarnes.com) -- the two longtime friends and bandmates share an insistence that people do their homework. In reference to MuGrass bands and their ilk who claim relation to bluegrass without putting in the time to learn the tradition, Barnes is philosophical.

"What has become de rigueur is the elements that they could quantify, not the elements that they couldn't quantify," he says. "And I think that's human nature. What you could quantify is that all those guys are dressed alike. They all come from middle- or lower-middle-class blue-collar backgrounds, or whatever, just for example. It's easier to quantify things like that than spirit, or invention, or creative spontaneity -- things you can't quantify. We found that over time, the things that you can quantify become the norm."

The course that Barnes has taken with his music, though steeped in the traditions and techniques of bluegrass banjo, operates outside the historical parameters of traditional bluegrass. This is as it should be for someone like Barnes whose creativity is not in reconstruction, but in achieving technical mastery and the subsequent dissimilation of form and content. While there's bluegrass in the music of Bad Livers, the Austin institution is not bluegrass.

"My recorded output is not bluegrass," concurs Barnes. "What I've tried to do is capture that same inspiration that these guys used, which is using the elements given to you, and those you've learned and absorbed, plus a certain degree of fly-by-night, seat-of-your-pants creativity to come up with a new thing."

In addition to Bad Livers, Barnes' own thing includes solo recordings that he makes at his home in Port Hadlock, Washington. He plays all instruments, mixes and burns the CDs himself, and sells limited editions of them on his Web site. He's also working with jazz guitarist and musical innovator Bill Frisell, with whom he will soon begin a tour of Europe. Barnes is animated and passionate about every one of his projects, and even though he is not actively involved in making bluegrass music, he is nonetheless adamant about people's perceptions of it.

"I get chills when I hear a good bluegrass band," he says. "When I listen to those [old Bill Monroe 78rpm records], I cry and I get goosebumps and my hair stands up on the back of my neck. It really moves me. ... Some of that modal playing is in two keys at the same time, which is a little Stravinsky if you think about it. Bagpipes and bluegrass pieces, they're modal, which means they're stuck between two keys. You can play either chord, it's weird. But that's what gives you that real creepy feeling. Have you experienced that yet in bluegrass? When listening to bluegrass, have you had that real creepy feeling?"

Yes, the first time I heard the Stanley Brothers' "The Lonesome River."

"There it is! That's what I'm saying. That's my definition of bluegrass right there. I can describe it in musical terms, that real wavering sort of perfect fit. If you hit it on the piano on the low end, it sounds like a cannon going off. And I think it has some sort of psycho-acoustic effects -- it does something to your brain. Sort of reaches back into your heritage or something -- some sort of Darwinian ethos."

Taking the banjo beyond preconceived notions and pre-established musical forms has proven no easy task for Barnes, as far as public reception goes. But, when you're playing music for the unrelenting demands of creativity, half-effort is not an option.

"I've dedicated my entire life to perfecting the banjo," says Barnes. "That's the truth. The more I do it the more I realize people can't deal with it. I think it's too intense. I don't think people can deal with the banjo. Ever since I started playing people have been saying, 'Hey this music is gonna come back,' but it's really not gonna come back. I think it's even more punk rock than punk rock in that respect. More stick to your guns and damn the torpedoes than punk rock has become since, if you think about it, it's more of a corporate statement these days."

There is nothing corporate about bluegrass. Limited potential for audiences, gigs, and innovation as prescribed by the boundaries of the genre -- not to mention the zealous guarding of the form and the technical proficiency required to play even passably -- offer significant barriers for young players trying to break into playing bluegrass. Still, whether or not they claim to be playing in the realm of traditional bluegrass, there are bands playing around Austin. If the Meat Purveyors, Two High String Band, Bluegrass Drive-by, or Fence Cutters are not bluegrass in the strictest sense, they do take conscious steps to include many of the music's attributes in their music.

|

|

"I'd like to call us a bluegrass band, and I love bluegrass," says Brent Livingston, banjo player for Bluegrass Drive-by, "but I also like different kinds of music, and I don't think we're smooth enough to be called a bluegrass band. I'd say we're more a glorified jug band."

Livingston is a former student of Danny Barnes', so the weight of bluegrass history is not lost on him, and neither is the importance of ability. Like many young pickers who love the traditional form, Livingston says that the sheer breadth of choices in musical styles that make up the modern musical spectrum are just too much to limit oneself artistically.

"I go down to the Artz jams, and I don't want to offend anyone down there. I like going to them, but I also like playing on stage and I don't want to abide by any rules those traditionalists have. I don't really care about that."

The Artz jams, in addition to being a way to hone one's chops, are a proving ground of sorts for bluegrassers in Austin. "I've had some great times down at Artz," says Livingston. "It can be pretty critical, but it's also nurturing. People do go out of their way to show you stuff."

While the choice venue for Bluegrass Drive-by gigs is Emo's over Artz, Billy Bright of Austin's Two High String Band prefers the quieter atmosphere normally reserved for bluegrass and acoustic music. The choices are limited, but for a reason.

"We don't want to play the other places," Bright says. "It's hard to play bluegrass in a bar. To me, bluegrass is meant for a certain kind of environment and if you're not playing it there, it gets hard to communicate -- not only to the band, but with the audience. It's hard to play in a rackety bar, and I've done that enough to where it doesn't matter if I don't."

Bright does not claim to be in a bluegrass band. Two High String Band plays a number of bluegrass standards, including a generous helping of gospel numbers and hyperspeed instrumentals, but in a live setting, the local group lacks a fiddle and banjo. Therefore, as Bright acknowledges, they're not really a bluegrass band.

At its heart, Bluegrass cannot be defined and measured by an absolute standard or formula. What makes bluegrass bluegrass is an adventurous spirit, an improvisational deftness, an ethereal quality that defies description -- a sound that spooks you. Something that wells up in your throat at the beautiful mournfulness of the high lonesome sound.

"It's just a matter of accepting who has influenced me and letting it be that way, letting the song come out," says Bright. "I like to use old phrases in a new context, in a way that you're not ripping someone off. It's the same with chord progressions and melodies, its all borrowing or stealing directly from old songs, know what I mean?

"That's what Bill Monroe was doing when he wrote his songs, too, in a certain sense. Everybody's got their influences."