Son of the Circus

Twistin' in the Wind

By Raoul Hernandez, Fri., Oct. 2, 1998

|

|

Getting Ely into a chair, finally, isn't quite as arduous as two lifelong friends and musicians battling a poisonous serpent in a cramped toilet, but when he's finally seated, going through a mental check-list of everything he's done since the April release of his 14th album, Twistin' in the Wind, it's clear the Lone Star icon has not been sitting idly by; a 15-city tour of Europe, another of the West Coast (45 cities), the Los Super Seven project. In fact, on this Saturday night, immediately following our interview, Ely is scheduled to meet Rick Trevino, Joel Guzman, and Max Baca for a Los Super Seven rehearsal. The next day, he's off to Los Angeles to meet fellow superheroes Los Lobos, central players in the Mexican-American all-star group, then, in short order, a House of Blues gig, a press day in New York, and a taping of Late Night With Conan O'Brien.

"Immediately, the very next day, I'm back here to do a play," says Ely, plenty of breath left.

A play?

"Kimmie Rhodes has been writing this thing about growing up in West Texas," explains Ely. "She wanted me to play the part of her Uncle Wes, who was a pool hustler I knew very well in Lubbock. He taught me how to play pool. I spent many days going down to the Golden Cue pool hall in Lubbock just watching him play. He was a poet and a pool hustler -- real quiet, shy guy, but he just tore people up left and right."

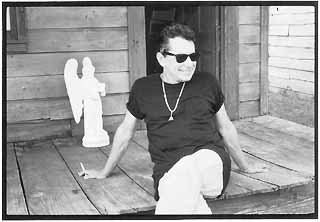

Even if audiences, Austin or otherwise, never get a chance to see Small Town Girl, a Joe Sears production put on for invitation-only audiences out at Willie Nelson's place this past weekend, the 51-year-old Ely has nevertheless spent the lion's share of his life tearing up audiences worldwide. Whether accompanied only by an acoustic guitar, paired with fellow Flatlanders Gilmore and Butch Hancock, or more likely, as leader of one of his many hard honky-tonkin' bands, Joe Ely has never delivered one of his Micheneresque tales of Texas with anything less than full, unbridled passion; a firebrand, that Ely, a tornado under the spotlight in the center ring -- a force of nature to be reckoned with, whether he was Down on the Drag, Lord of the Highway, or Live at Liberty Lunch. Or as the case may be now, Twistin' in the Wind.

For the majority of his two-decade recording career, Ely has torn it up for MCA, producers of 10 of the 14 albums under his name. After discovering him in a Lubbock honky-tonk "out in the middle of a cotton field" in 1976, MCA put out Ely's eponymous debut the next year, and continued releasing his albums -- Honky Tonk Masquerade ('78), Down on the Drag ('79), Live Shots ('80), Musta Notta Gotta Lotta ('81) -- until 1984's critical and commercial disaster, Hi-Res, after which he and MCA parted ways.

Rebounding with two creative-peak albums for Bay Area-based indie Hightone -- Lord of the Highway ('87) and Dig All Night ('88) -- Ely and MCA came back together with the spontaneous combustion of Live at Liberty Lunch, following it up with three of the songwriter's strongest and most cohesive releases, Love and Danger ('93), Letter to Laredo ('95), and Twistin' in the Wind. In fact, Ely was out on the road in support of the latter album, not yet out six months, when the Chronicle reported in August that he had been dropped once again by the label [Vol. 17, No. 49].

"Yeah, the timing [wasn't good]," acknowledges Ely. "I was still out there supporting the record. In that way, the timing was bad. But they're still supporting this record -- still buying ads in the papers. I just don't know how much longer I can support it, because I have to go ahead and start thinking about what I'm gonna do next.

"I can't linger on something knowing that I'm not going to be starting a new record for them."

The news must have come as a shock?

"No, not at all," he says easily. "I knew the minute that Seagram's bought MCA and then Polygram, I knew that was gonna cause a lot of friction. I had a working thing going on with MCA Nashville mainly because of [its president] Tony Brown. Tony liked to have a connection in Austin. He's always been real excited about the things coming out of here. But you know, I don't sell platinum albums. I never have. Also, I don't do country albums, like Nashville. So in a way, it was never quite the right label for me to begin with, but because of Tony's connection, I liked working with them."

More a Legend Than a Band

|

|

That Ely doesn't seem the least bit worried about losing a recording contract is not the least bit surprising. Indeed, he's not one to linger on something; Ely says that as soon as he sees a finished CD, he starts work on the next one. With or without MCA, he will make albums -- make albums, hit the road in support of them, then return home to write about what he found out there, and start all over again. That's been the cycle ever since Joe Ely hit shelves in 1977. This time around, Ely says he's thinking about making another live album, maybe calling David Grissom to come down and join Jesse Taylor, Lloyd Maines, Teye, bassist Gary Herman, and drummer Donald Lindley -- his current band -- for some locally recorded shows.

"I've got a lot of calls from different labels that are interested in doing stuff," reveals Ely. "But you know, I've been thinking lately. I have so many things that I've worked on here over the years that have never been released: I've done a solo acoustic album, I've done several full band albums I've never released. And I'm thinking I might start a little label, myself.

"I'm just kicking that around, mainly because there's so many projects that I've started and worked on over the years that I've kinda kept them close because they were so personal. I might be completely insane to start another label, but why not? There's already 400 labels in Austin."

When talk arises concerning future "projects," as Ely calls them, and it becomes clear that for the present moment anything goes, one subject in particular seems to come up naturally: the Flatlanders. The Lubbock triumvirate of Ely, Gilmore, Hancock, the Flatlanders came together in 1970 when all three budding mystics were fresh out of high school and looking to stake their own claim to the legacy of their hometown's spiritual and musical muse, Buddy Holly. A sole album was recorded by the three in Nashville by 1972, but when it failed to come out (released finally by Rounder Records in 1990 as More a Legend Than a Band), the three went their separate ways.

More than 25 years later, with the release of the soundtrack to Robert Redford's film The Horse Whisperer in April, the now-mythic Flatlanders actually found themselves with a new song out there for public consumption, the freshly recorded and bucolic "South Wind of Summer." According to Ely, the "project" came about when he met the film's supervisor in Tony Brown's office. Taking a liking to "Roll Again" from Twistin' in the Wind, she took the song to "Redford's people," who casually suggested Ely should take up with his ol' buddies and write and record a brand-new song just for the film. The three compatriots wrote three songs in a day and a half.

"That's when we realized we had never sat down and wrote anything with the express purpose of it being a song," explains Ely. "We realized we could do that -- all three of us. We always thought that we came from such different places that we couldn't come together on one song. That's triggered a few things. We have even talked about making another Flatlanders record, which would be great fun."

So...?

"I've had so many people ask me about that -- record companies and just fans that would love to see what we could come up with. I think there is a chance, yeah. We've talked about it and all agreed it would be a great, fun project to do."

Fun enough, apparently, that already a handful of Flatlanders reunions have taken place this year alone: one at South by Southwest during a Twistin' in the Wind preview/listening party at Ely's house, another on The Late Show With David Letterman, and a third that followed the television show taping when Ely and Hancock showed up at Gilmore's post-Letterman gig at New York's Mercury Lounge. As a matter of fact, Ely says that only the night before this interview the Flatlanders reunited for an impromptu gig in Lubbock after Gilmore and Hancock received their stars on the town's music walk of fame. The trio played well over two hours.

"We played forever," laughs Ely. "We played songs we hadn't played together for years. It was such a great feeling. I think [a new album] is something that's destined to happen. And now might be the best time since I'm not tied up with a label, and neither is Butch. Jimmie is probably gonna be signing something with some label soon, but as of now, he's not."

Lord of the Highway

If a full-blown Flatlanders reunion is destined to happen, so too does it seem similarly fated that Ely became a musician in the first place; he the truest of troubadours, always on another stage, in another town, bringing Texas vistas to audiences who might never even set foot on Lone Star soil. Born in Amarillo on February 9, 1947, Ely says his fate was already carved out for him when his family moved to Lubbock when he was 12.

If a full-blown Flatlanders reunion is destined to happen, so too does it seem similarly fated that Ely became a musician in the first place; he the truest of troubadours, always on another stage, in another town, bringing Texas vistas to audiences who might never even set foot on Lone Star soil. Born in Amarillo on February 9, 1947, Ely says his fate was already carved out for him when his family moved to Lubbock when he was 12.

"I guess being born on Route 66 destined me to be a highway man," says Ely thoughtfully. "My granddad came into West Texas at the turn of the century with the railroads. My daddy worked for the railroads. So, I grew up on a train. That was a big part of it. Finding music was the other piece of the puzzle."

Ironically, it was the music that found Ely; first when renowned fiddlemaker Jimmy Meeks made the 8-year-old Ely his own little violin, and later when the man from whom Buddy Holly had taken Hawaiian steel guitar lessons came to the front door. "Only in Lubbock can you imagine a guy coming around door-to-door selling steel guitar lessons," chuckles Ely. "He had a little amp in one hand with a palm tree on it, and a steel guitar in the other, and he'd ask if he could come in and give a demonstration."

By his 14th birthday, Ely says he knew he was going to "follow music forever," putting together a series of bands in high school and playing dances and parties around Lubbock after his father died and he had to contribute to the family's finances.

"The whole thing about Lubbock was real exciting," says Ely, "because Buddy Holly had died by the time I got there, but there was this whole underground spirit of Buddy Holly in all the musicians, and I got to know all those guys -- a lot of the people who knew Buddy. There was a real kind of mystery and magic there.

"It was real prevalent in all aspects of Lubbock music. That was a real strange mystery there. Where did all this come from? How did it end up in Lubbock -- this dusty ol' cotton town? Then I got to thinking about Roy Orbison, from just a few miles south of there, and how these guys could do these beautiful chord progressions and these wonderful melodies."

It was after high school, then, that Ely met and became friends with Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Butch Hancock.

"Jimmie was like a well of country music," explains Ely. "He knew everything about it. And Butch was from the folk world. I was kinda the rock & roll guy, and we almost had a triad. We hit it off and started playing a lot together. That opened up a whole new world I had never known existed."

Estimating that the Flatlanders' initial alliance lasted about two years, including the recording of their only album -- an atmospheric, often lonesome folk album defined by the flying saucer sounds of a musical saw -- the group's dissolution in 1972 left Ely free to do that which he'd been straining at the leash to do: roam.

"For the next few years, I took off with a sleeping bag, backpack, and a guitar," says Ely. "Just took off across America -- back and forth: West Coast, East Coast, New Mexico. I had places I was just kind of in search of. I was looking to see where the well was. I followed the tracks of a lot of people who I admired -- who inspired me. People like Woody Guthrie, the ol' blues guys on Highway 61. I just had to go to these places. I'd hear a song about it, and have to go there, of course. So I'd go there by whatever means I could."

Ely acknowledges that he was looking for the same mythology that informs so many of the songs in his considerable canon of compositions, everything from the fan favorites like "Me and Billy the Kid" and "Grandfather Blues" to almost anything off Letter to Laredo, and new songs like "Up on the Ridge" and "Queen of Heaven" from Twistin' in the Wind. Of course, admits Ely, there was never really anything to find; it was the journey, not the destination, that held all the answers.

"I look back now, and I see that I was making it all up," says Ely plainly. "In the words of Tom T. Hall, some people can go around the world and never find anything to write about, while others can walk around the block and see the whole world. I came to that conclusion after I was out there spinning around for about 3-4 years, just jumping freights. I'd end up in New York City or Venice, California, Berkeley, San Francisco -- up in the mountains of New Mexico.

"Then I came to this blinding flash of light in Manhattan, sleeping in a theatre prop room up above some theatre where the subway would rumble the whole building. I said, 'Man, I gotta get home. I've been up here six months. I've seen what there is to see.' I wrote some great songs up there -- a lot of the songs I did on the first couple of records -- but I realized, 'This isn't my place. I've gotta get back to West Texas.'"

And when he did, there was one last obstacle standing between him and some cotton field out in West Texas: The circus -- Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, for which Ely worked one season, traveling all through Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, taking care of the llamas and the "World's Smallest Horse." That was up until the day he was almost trampled by a parade of elephants.

"I got knocked out when they were leading the elephants in," remembers Ely. "A horse kicked me and knocked me out, and the elephants were coming in. The lion tamer, Gunther Gebel Williams, actually drug me by the collar -- somebody said -- over to the side, slapped me around until I kinda woke up, then ran off to do his act in the middle ring. I cracked several ribs, couldn't hardly breathe, and figured that was the end of my circus days.

"I guess it was something I had to do to pass from one world into another."

Letter to Laredo

The world found on Twistin' in the Wind will be unmistakably familiar to this state's sons and daughters. The images conjured in songs like "Up on the Ridge," "Teach My Chihuahua to Sing," "Sister Soak the Beans," and "Nacho Mama" are as vividly Texan as a passage from a Larry McMurtry novel; a carnival of characters that could only come from one place. Saying he's always been fascinated by movies, pointing out that the songs on Hi-Res were originally conceived to accompany a short film, Ely makes no bones about why Twistin' in the Wind evokes his home state with every note played.

The world found on Twistin' in the Wind will be unmistakably familiar to this state's sons and daughters. The images conjured in songs like "Up on the Ridge," "Teach My Chihuahua to Sing," "Sister Soak the Beans," and "Nacho Mama" are as vividly Texan as a passage from a Larry McMurtry novel; a carnival of characters that could only come from one place. Saying he's always been fascinated by movies, pointing out that the songs on Hi-Res were originally conceived to accompany a short film, Ely makes no bones about why Twistin' in the Wind evokes his home state with every note played.

"No matter where I am, I'm still thinking about some long stretch of dirt road with nothing but fence posts and sky. I can be in downtown Manhattan and be writing, and that's where I always come back to.

"There were a few times back in the early Eighties when I was practically living in London and touring with the Clash where the songs almost got away from that. I almost left my home. When I started trying to write a record about 'Out There,' it never worked. It always seemed I had to come back to where I know about. And on the last two records, I really wanted to capture the things I know about. Twistin' in the Wind was really like coming home."

A natural outgrowth of 1995's Letter to Laredo, Ely's previous effort for MCA, Twistin' in the Wind blows like a storm up from the Gulf, leaving behind the border images of Laredo, yet capturing all the fence posts and big sky along that desolate dirt road north to the Panhandle. In that sense, the two albums are united by something other than the best reviews of Ely's long career.

"Letter to Laredo was a total experiment that could have just hit a wall," admits Ely. "I had no idea what I was doing. I was really fascinated with taking off on some wild fork in the road. I had just come back from traveling around Spain, seeing all of Gaudi's stuff...

"Running into [Flamenco guitarist] Teye was completely by accident. And having these songs I had written over there. That kind of brought about a change, because I said, 'Here's the song. Can you make anything of it?' And Teye says, 'Oh yeah. Here's the way you play it.' That was kinda like, 'Wow. Can I bring the Texas thing into this?' because I had always loved the music of Mexico, but coming from the Spanish guitar -- the Spain thing -- bringing it into Texas, it became a new, different thing that I could get into. And I'm always looking for some other angle.

"And then Twistin' in the Wind came out of that, and even more, going back to almost the very first record I made, putting Lloyd and Jesse together, and having the steel winding through everything. I starting writing it when I was out on the road. We played the hell out of Letter to Laredo. We went to Europe twice with it, zig-zagged across [this] country several times. I started writing Twistin' in the Wind, then, out on the road. Things like 'Up on the Ridge' came from that."

With Teye's fleet-fingered Spanish guitar fanning Ely's foreboding intro, the song building steadily until it explodes in a chorus of rising guitars and Lloyd Maines' eerie slide, Twistin' in the Wind's explosive opening salvo, with its refrain of "Up on the ridge, there's a highway headed home, where the ramblin' men must leave their sin," manages to harness all the wanderlust and restlessness inherent in Joe Ely. It is the Lubbock firebrand in a song.

"It's like facing your fate," says Ely, explaining the song. "You're facing an unknown. You have a glimpse that there's something out there. It could be danger, could be a big change, but you knew there was something that frightened you a little bit, and at the same time, you had the choice of reeling it back in, coming back home to where your friends and family are, or else following it. I guess in the song, I kinda did both. I reeled it all in, decided the place I really love and the reason I've never moved to Nashville or L.A. is ...

"You know," says Ely interrupting himself. "I got to thinking about it the other day. I've never done a really Texas label record. Every record I've ever done has been either West Coast or Nashville. And I started thinking, the place I really love, the reason I've never moved out there to be in the center of all the media, I just never liked it. I just could never write when I went to those places. The place I really love is the place that I grew up, Texas.

"And that's what I'm now looking to find -- what the new Texas is. There's still the cowboys out there on the ranches. There's still kinda the old Wild West, but the corporations have taken over. It's become 'Western Real Estate' instead of the Wild West. That's still a record I'll go in search of one of these days; finding what is myth, and how much myth is still carried over into modern Texas, where we're still shooting water moccasins."

Joe Ely plays at the Dessau Music Hall on Friday, Oct.2.