APD Pot-Hunters Are Data-Mining at AE

Are you using 'too much' energy? Inquiring drug cops want to know.

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Nov. 16, 2007

According to federal prosecutors, local Drug Enforcement Administration agents, and at least one Austin Police Department detective, for nearly three years Austin resident Travis Colby was involved in a "conspiracy" to grow and sell large quantities of marijuana cultivated inside several Austin properties he owns. Colby denies any involvement in the alleged operation – instead, he says, it was a former business partner and others who'd rented property from him who were apparently cultivating. The available court documents in fact contain little to suggest that Colby was involved in or even aware of any marijuana-growing operations.

However, the court records do reflect – and city utility documents appear to confirm – that the manner in which Austin police developed a case against Colby, and against at least three other persons, was questionable and possibly based on an illegal search. Colby's lawyer, David Dudley, argues that APD Detective Jeff Haynes used energy-consumption information from thousands of Austin Energy customers – without those customers' knowledge or consent – in an effort to find and focus upon AE customers who, in Haynes' opinion, regularly consume more kilowatt-hours than he believed "typical" for the size of their residence. In other words, rather than developing an investigation and then accessing a discrete and particular set of energy-consumption data in order to verify other evidence that suggests a growing operation might be under way inside a particular house, Haynes was working with AE, and in particular with business process analyst Mark Coffey, to troll through thousands of records from across Austin in an effort to find energy-consumption "targets" to pursue.

AE officials insist their cooperation with APD is required of the city utility – pursuant to a 1994 ruling from the Texas attorney general's office and supported by federal legal precedent. Dudley believes the revelation is "really quite shocking." What has happened in Austin, he says, runs counter to a national trend to tighten security policies regarding customer utility information. (For The Austin Chronicle's Kill-a-Watt Challenge, by contrast, AE required each participant to fill out an online form giving AE explicit permission to access and review their account information. Not so for the APD.) Evidence Dudley has uncovered "seems to indicate not only [that police were given] their own password" to access AE's customer database but also "that AE is acting almost as a law enforcement agency [helping] to facilitate law enforcement search warrants."

According to Austin Energy spokesman Ed Clark, there isn't anything illegal or improper in the way the AE data has been used by APD. "Yes, it's legal," he says, "because we wouldn't do something that's illegal." He notes that federal courts have ruled that even where utility data is the "initial impetus" for an investigation, there is no invasion of an individual's privacy. UT Law professor George Dix says that under existing law, when third parties (such as AE) maintain customer records, such as utility account information, consumers do not generally retain "any privacy interest" in the information.

However, he said, the question of whether such data by itself is enough to support probable cause for a search warrant is an entirely different matter.

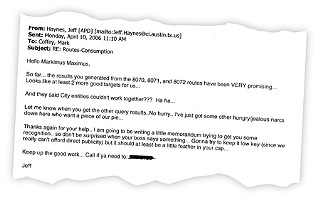

Fishing for Pot

The Chronicle has obtained e-mails between Coffey and Haynes, along with several lists of AE customer data that Haynes apparently used to fish for potential pot-growing operations. In combination with court documents related to Colby's case, the records paint a disturbing picture of how APD has been conducting at least some of its marijuana investigations – and how the information was used, at least in Colby's case, to develop probable cause for a search. The documents also reflect an APD officer clearly pleased with the success of his data-mining operation and simultaneously wary that his methods might be inadvertently revealed. "So far ... the results you generated ... have been VERY promising. ... Looks like at least 2 more good targets for us," Haynes wrote in an April 19, 2006, e-mail to Coffey (whom he addresses as "Markimus Maximus" – or, in other e-mails, as "da man"). "Thanks again for your help. ... I am going to be writing a little memorandum trying to get you some recognition ... so don't be surprised when your boss says something. ... Gonna try to keep it low key (since we really can't afford direct publicity) but it should at least be a little feather in your cap."

In a September 2006 search warrant, seeking access to Colby's home, Haynes explains he "initiated" his investigation into the pot-growing operation he alleges Colby is a part of by "checking the city of Austin computerized utility records" for a particular address in Austin – an address not connected to Colby. Once Haynes acquired the utility information, he checked Travis Co. Appraisal District records to determine the square footage of the residence (a duplex) at issue. Cross checking the utility information with the tax information, Haynes wrote that he "immediately observed that for structures of their size the electrical consumption was disproportionate (very high) for normal residential usage. Your affiant knows from experience and training this to be typical of a residence where marijuana is being grown indoors due to the high intensity lights, fans, and pumps used in the process." According to Haynes, he could make this assumptive leap because he has "significant experience analyzing computerized electrical consumption data" that he has "utilized ... in the successful investigation of numerous marijuana cultivation operations." Haynes subsequently ran other checks to see who previously held a utility account at the suspect address – noting that when at least one other person lived there, the consumption had also been "significantly higher" than he believed likely for a home of about 1,000 square feet. Haynes then apparently checked other properties where the individuals held, or previously held, accounts, comparing that information against home size; Haynes then checked to see who actually owned several of the other properties in question, which is where he found Colby's name.

Aside from the utility data, however, there doesn't appear to be much substance to the Haynes investigation – he notes seeing several people acting "suspiciously" outside a Drive-Thru Postal location, though, notably, he never sees anything illegal take place. Still, the information compiled in Haynes' affidavit was apparently enough to convince former Travis Co. Judge Jon Wisser that there was sufficient probable cause to search five properties, including Colby's home. At one of Colby's rental properties, police seized 20.2 pounds of pot and equipment for cultivation. Notably, police found no contraband at Colby's residence, although they did seize his gun collection (police allege the guns were used to protect the illegal pot-growing operation). Now, the feds have taken on the case, charging Colby as a conspirator in his tenants' growing operation – and they're invoking federal seizure laws in an attempt to take possession of each of Colby's properties.

Aside from the mined utility "evidence," there is little of substance to suggest that a growing operation would be found, Dudley notes. In other words, he argues it is unlikely Wisser would have found probable cause to search the properties at all without the information culled from the AE database.

In a short statement released by APD last week, officials said that the department "complies with all state and federal laws in regard to investigative measures. The people of Austin expect no less. To safeguard the effectiveness of those measures and the success of its investigations, APD does not discuss specifics," the statement continues. "However, every case must go through the legal process where all tactics are reviewed. APD is confident that the measures it utilizes follows the law."

Trolling the Data

Moreover, according to a series of e-mails between APD Detective Haynes and AE analyst Coffey, it appears that mining utility information for thousands of customers has been used as a key to ferreting out possible lawbreakers based solely on raw consumption data. For example, on April 4, Haynes asks Coffey to run a search for "anyone [using] over 4,000 [kilowatt hours per month] over the last few months or so," which he says might provide a "broader range" of possible suspects. In another e-mail, Haynes tells Coffey to take his time generating information because he was "still working a few cases from the last batch you gave me." Besides, he notes, his suspects will "still be growing next month." It is unclear how many fishing expeditions Haynes and Coffey have embarked upon since APD signed the utility database use and confidentiality agreement in 2002, but since March 2006, it appears Haynes has received at least four batches of utility user data – including at least two batches with information on thousands of utility customers from all over Austin. One such search provided APD with 44 printed pages of account-holder information for about 2,000 customers living in 38 city ZIP codes. "And they said City entities couldn't work together???" Haynes wrote in one e-mail to Coffey. "Ha ha."

While getting city entities to work together might be an admirable goal, Dudley maintains that the APD's use of utility records to establish possible leads on marijuana growers appears to be a violation of the Fourth Amendment's protection against unlawful search and seizure. Importantly, he argues that in Colby's case, Haynes improperly relied on the utility data to form "opinions that various properties may be housing marijuana cultivation facilities due to the supposed abnormally high power usage of their occupants" – opinions that he transformed into the basis for probable cause to search Colby's home.

In a motion seeking to suppress the results of the APD searches of property owned by Colby, he writes that the utility information APD used provided police with a window into the private lives of numerous utility customers. Colby's case is quite similar to a 2001 U.S. Supreme Court case, U.S. v. Kyllo, Dudley argues, in which the court held that police use of a thermal-imaging device aimed at a private home "to detect relative amounts of heat within the home" (in an effort to determine whether Danny Lee Kyllo was growing marijuana there) was a violation of the Fourth Amendment. "In the home ... all details are intimate details, because the entire area is held safe from prying government eyes," Justice Antonin Scalia wrote for the court – and that includes "the detail of how warm – or even how relatively warm Kyllo was heating his residence." During a suppression hearing last month, Dudley says, one AE employee conceded that electricity consumption information can offer a window into a person's private life. It can reveal "when someone is home or not, when someone showers or goes to bed," Dudley says. "There are all sorts of personal things you can find out about somebody. The bottom line is that [utility use alone can reveal] a lot [of] very personal, intimate things."

Dudley also argues that Haynes misled the court by claiming to be an expert in analyzing utility usage. Haynes' claim that energy consumption is directly related to the square footage of a given structure is tenuous at best, Dudley argues. Yet Haynes' opinions about "typical" consumption formed the "basis of his probable cause statement" seeking permission to search Colby's residence. In a memorandum filed with the court, Dudley cites the conclusion of a defense expert, Buzz Thielemann, an energy consultant from Oregon who previously worked with law enforcement during his tenure with Pacific Power and Light, that "power usage differences between properties of a similar size are, in and of themselves, far more likely to be attributable to innocent factors – such as one house having electrical heating while another uses gas – than to [indoor] marijuana cultivation." (Assistant U.S. Attorney Douglas Gardner argues, oddly, that Haynes never purported to be an "expert" and that regardless, Colby lacks "standing" to contest a search of at least one of the properties – the property where marijuana was actually found – because Colby was merely the property's owner and not the current resident. Yet the feds are using the evidence obtained from that search in order to charge Colby as a party to the pot-growing enterprise.) In all, Dudley argues that the manner in which APD used AE information in general, and in Colby's case in particular, is "disturbing." The "totality of the way this was conducted – culling, randomly, blocks and blocks of residential [properties] to look at electrical consumption data," he says, constitutes a "series of invasions of privacy."

Whether Dudley's argument will prevail in federal court is uncertain. His argument that the culling of AE customer records is as invasive as using a thermal-imaging device, as in Kyllo, may not be compelling (at least not under the current but arguably outmoded interpretation of the Fourth Amendment). UT Law professor Dix believes that Dudley will have a hard time tying the release of utility data to the facts of Kyllo; nonetheless, Dix says the Supremes' rulings in this area may be shortsighted. While the court may say that a person can't reasonably believe that his utility records are private, the real question is whether that is something that a "reasonable person" would expect. In other words, Dix says, the "basic question is how you decide that schmucks like me" wouldn't object to the disclosure of that data. Under current precedent, he says, Dudley and Colby are facing an "uphill fight."

At press time, federal District Judge Lee Yeakel had not yet ruled on the motion to suppress evidence; Colby's trial is currently set to begin Jan. 14.

Click here for a sample of the information AE provided to APD

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.