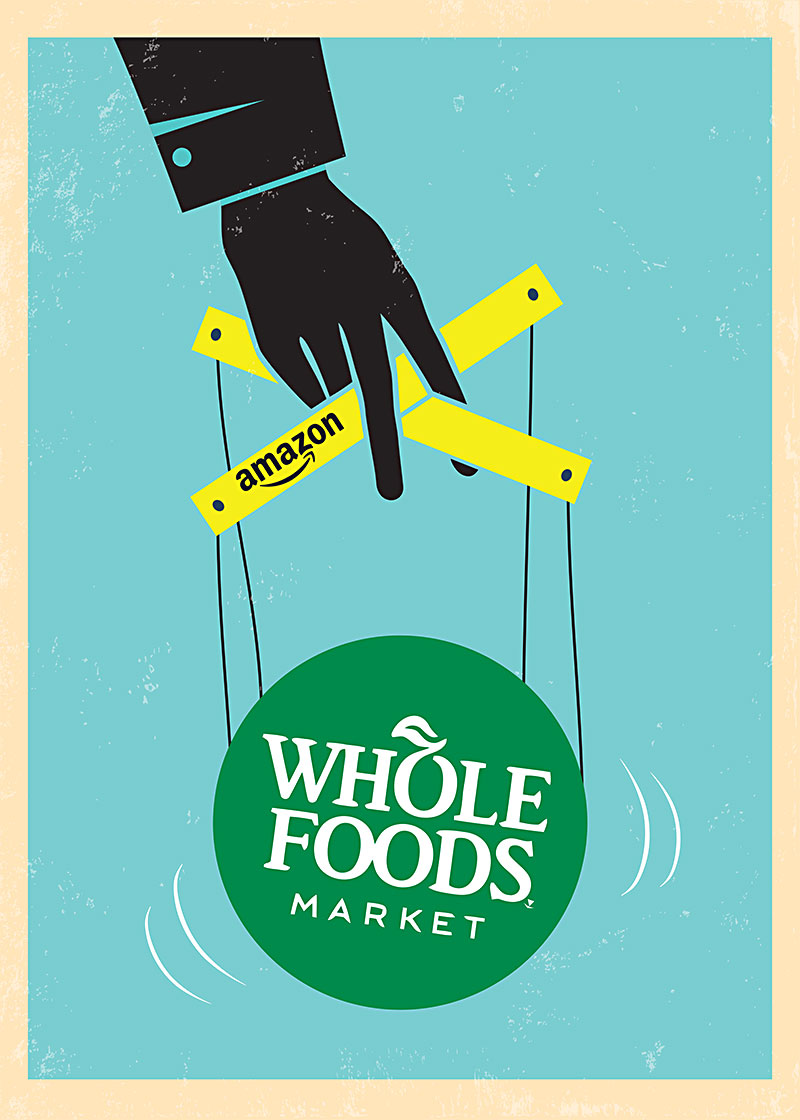

The Amazon-ification of Whole Foods

Small products struggle to keep the attention of the Goliath of global efficiency

By Jessi Devenyns, Fri., Oct. 6, 2017

When Amazon acquired Whole Foods in August for $13.7 billion, scrutiny about the consequences of implementing the distribution giant's model over that of a traditional supermarket skirted around one aspect: What effect will price cuts have on local suppliers?

In the grocery industry, innovative competition has been lagging, and few technological advances have been introduced to alter the service chain hierarchy. Amazon, however, is striving to fundamentally change this structure – perhaps, in part, because some estimates are showing $668 billion in opportunity for them to harness, according to the Food Marketing Institute.

The problem with implementing efficiency at all costs – Amazon-style – is that it hasn't always benefited local businesses or the types of small-producer products that make Whole Foods a bastion of local products. In fact, a quick search on Amazon Prime Pantry for "artisan" or "local" food products only returns a few dozen items including Burt's Bees and Red Vines licorice – neither fitting the bill. Pete Svehla, wholesale manager for Johnson's Backyard Garden and a former employee of Whole Foods, says that Amazon's cost-cutting, global mindset hasn't changed as it begins to integrate its model into the grocery chain that has historically advocated for local producers. "They mentioned that there was going to be a policy coming up soon for when we send [an order] to their distribution center: Once it's received, if we are off by 1 pound, everything gets sent back. And that is very, very hard because we are dealing with perishable products," he explained. He believes that these rules are being set to dissuade local farmers and encourage high-volume producers to supply the store.

Very little about Amazon is local, and a glance at their mission statement makes that clear. According to their website, their vision is to "build a place where people can come to find and discover anything they might want to buy online." Conversely, Whole Foods purports the ethos of purchasing regionally to give individual stores the autonomy to forge relationships with local suppliers and "bring the highest quality food to our customers," said John Mackey, Whole Foods Market co-founder and CEO in a statement on August 24, regarding the Amazon merger.

This demand for the "highest quality food," however, is showing unintended consequences. "They're demanding produce with no blemishes, no discoloration – almost extra-perfect produce," says Svehla. "So it's harder to meet their expectations with the quality they want and the quantity and at the same time wanting some of the cheapest prices." Instead, Whole Foods seems to be finding their ideal products across borders. Svehla noted that increasingly products that were labeled "local" also included fine print which stated "made in Mexico." Not only does this practice chafe against the values that Whole Foods has traditionally upheld, but, according to a May report by The Washington Post – which Amazon owner Jeff Bezos owns – sourcing organic food from overseas is a practice that dilutes organic standards. The Post reported "the pesticide residue results that were obtained by the Post also indicate that enforcement of 'USDA Organic' rules for pesticides are uneven and possibly arbitrary, with results depending on the inspection agency."

It's not all about Amazon, though. The shift toward a more centralized model began last year when Whole Foods eliminated around 2,000 jobs, integrated automation for stocking shelves, and moved all its nonperishable buying to the Austin, Texas, headquarters. Although he agreed that 2016 saw some significant changes, Dan Gillotte, chief executive grocer at Wheatsville Food Co-op, argued that the path was laid almost a decade ago. Whole Foods, he explained, had an initial push toward centralization that caused a multitude of local producers to be forced out. "I expect that, potentially, what happened a number of years ago could occur again," said Gillotte. He also noted that although Amazon's involvement is likely to exacerbate the problem, he has not yet seen any specific cases.

Amazon has made its fortune by selling products at sharply discounted prices while driving the bulk of their revenue through membership and other provided services like Amazon Video, Kindle E-readers and books, and Amazon Music. Gillotte observed that if past behavior is predictive, and Amazon translates this model to the fresh grocery industry, it will begin to pull individual local producer threads from the fabric of Whole Foods suppliers. "It appears that Amazon doesn't need to make a profit, so it makes them extremely hard to compete with," he said.

Such a move could also boost large, industrialized organic operations – a further detriment to small and midsized suppliers. When asked about the potential of this happening considering Amazon's reputation, Brooke Buchanan, the senior VP of communications for Whole Foods, said, "We will continue to source from local and small producers in stores across the country."

Svehla argues that consolidation will be the only way for local producers to survive. "I see local farms merging themselves together to become big enough to be able to supply. It's getting to that point where local farming is probably not going to survive for Whole Foods because the [individual farms'] operations just are not big enough," he said.

However, the real harm from this purchasing consolidation will come if Amazon pushes for price concessions on top of Whole Foods' already low margins that leave producers few choices other than to compromise on food quality and environmental standards in order to continue to offer their products at the country's largest organic retailer.

Svehla describes the financial struggle that local producers are facing when supplying Whole Foods, saying, "What I'm seeing so far is that the demand for our produce to go into Whole Foods is still the same. But they're expecting lower prices when we're already trying to match a 45 percent margin just so we're profitable."

Other local producers are more optimistic. One local farm, who did not wish to be named, observed that a profit margin reduction is certainly possible if Amazon chooses to centralize its buying, but that it will be incredibly difficult to do so with perishable commodities. Nevertheless, if it does occur, the farm representative said that there won't be a lot of room to reduce prices.

Despite the worry that many local producers are experiencing, there are promising signs that Whole Foods might stay true to its roots as an advocate for local farms. Most notably, Rachel Malish, another public relations spokesperson from Whole Foods, said that there was no intention in slowing down the search for new products and offering financial support through their internal loans program. "We don't currently have plans to change the Local Producer Loan Program. We continue to accept and review applications and have given more than $22 million in low-interest loans since 2007," she said.

Svehla, on the other hand, remains insistent that the core values of support and financial aid are more of just a facade at this point. "Now being on the outside, one of their core values is to support micro-loans. We're seeing the prices they're getting for whole trade; the price that they're paying is ridiculous," he said.

This price reduction trend does not seem to be stopping with Whole Foods. "In general, we're finding pressure on price regardless of whether Whole Foods and Amazon are going to be pressing price or not. We've been working on lowering our prices for the past few years because we recognize that people are looking to save wherever they can," said Gillotte. Even Svehla agreed that being asked to reduce the price is a fairly common practice that local producers are willing to accommodate, but that there are limits. He explained that after meeting with Whole Foods buyers post-acquisition, "We [JBG] can't make it work with Whole Foods with our current prices."

Svehla says the question now appears to be, "How low can you go?"