Take a Walk on the Wild Side

The ancient art of foraging for food is aged to perfection

By Jessi Cape, Fri., April 4, 2014

It's odd to describe an activity humans have participated in since the beginning of their existence as a trend, but here we are: Foraging is making a comeback. Urban foraging, specifically.

A while ago I stumbled upon a blog post from Johnson's Backyard Garden describing the wonders of purslane. You mean this little sidewalk-crack weed is not only extremely nutritious (and free!), but it tastes good, too? From there my memory flooded with the many foraged items I learned to pick and savor during childhood: wild Wisconsin blueberries, enough Texas pecans to fill a belly and break a back, and sweet droplets of nectar from wild honeysuckle vines. At some point, of course, I grew up, forgot, and proceeded to purchase everything from the grocery store or farmers' market. But I'm not the only one to have overlooked the enormous bounty – from weeds to bugs – living just outside our doors; several Central Texans are ready to help us discover our roots.

Fringe, but Not Forgotten

Until approximately 12,000 years ago, when the first agricultural systems were developed, across every border and cultural divide, foraging was the predominant means of sustenance. Fast forward several thousand years, and the practice has dwindled significantly. Minor bursts of popularity during recent decades have helped the practice maintain cultural relevance, from the Woodstock years' boom of interest in nature's treats to a longtime presence in the literature and film worlds. The lost art is gaining momentum for a variety of modern reasons, too, including economic hardship, increased interest in sustainability and ecological well-being, and a desire to reconnect with nature and food.

"I think foraging fits in with any city, any town, any rural area, and any wilderness," says Eric Knight, one of the Earth Native Wilderness School's main teachers of edible and medicinal plant classes. "It's part of who we are as humans. Up until very recently, archaeologically speaking, we found our food outside – not in a grocery store, not at a restaurant, not at a market. And everyone participated. Young, old, men, women. ... Life revolved around finding food, and everyone pitched in."

Even those quietly participating – maybe snacking on a rogue apple or gathering wild onions by the creek – are enhancing these early stages of a foraging renaissance. The variety, ease of access, and low cost are poised to build up the vested interest in the food in our city. Says Knight: "There is already a network of avid foragers in Central Texas that is effectively bringing people from all walks of life together to obtain free, healthy food and appreciate our natural world. I think those two outcomes of foraging are inherently powerful community builders."

Paige Hill Oliverio, founder and director of Urban Patchwork Neighborhood Farms, forages for her own consumption and also sells to local chefs. She agrees that urban foraging may be a secret recipe for success. "I was taught at an early age that food and medicine are all around us. ... We don't have to struggle to cultivate everything on intensive farms," adds Oliverio. "I always tell people that we need to tap into the generation of people who are the oldest right now, and people who have just recently immigrated here to learn age-old practices that we're not being taught anymore. ... Sure, with diet being mostly driven by what's available in the grocery stores now, people's food habits and 'food cultures' are dwindling, but I really think foraging helps us tap into cultural diets rather than the diets being forced into an unfamiliar pattern."

So, foraging exists positively on a global time-continuum, as well as here locally, but surely it must be elitist. Or at least impractical. Right? Wrong. Herein lies the beauty: Armed with knowledge available almost anywhere (online, at the library, in local classes, etc.), anyone can experience the ancient art of harvesting, processing, and preparing food by scouring their neighborhood, identifying the wild edibles, and incorporating the treats into serendipitous meals.

Food in the City

As a resurgence of naturally derived, but often not naturally legit, food terms have infiltrated even the most commercial of food products, a return to foraging offers a simple way to boost the global food system by inspiring interest in new sectors. Oliverio says, "Now that people are familiar again with 'urban food,' [Urban Patchwork is] focused on how people can find and grow food in everyday places – the old way. We facilitate people working together on food justice and food system projects that last, like neighborhood 'food forests,' foraging and preserving, homesteading, backyard meat production, and methods that ensure biodiversity, a healthy ecosystem, and resource conservation."

In Austin, many of our beloved chefs offer nightly examples of the world of foraged possibility, but perhaps it's time for the nonindustry types to participate in this cultivation. What blooms today could be picked soon and spun into a brand-new dish; what lies on the ground can be preserved, pickled, canned, or cured. When both chefs and diners revel in nature's lovely spontaneity – with sometimes weekly or daily shifts in availability – to inspire meals, food culture begins to offer a chance for positive, more sustainable change.

Says Knight, "When you get food so directly from the land, with no middle men, not even farmers, you can't help but to assign value to the plant you ate from and want to protect it and its surroundings. Hopefully this will foster a conservation ethic that, frankly, I think is needed in Austin during this time of unprecedented growth."

But as with any game-changer, rules are essential for keeping the peace.

Some Kind of Nature

Every adventure story has a dark side. The predominant concern for foragers is twofold – safety and ethics – but simply asking questions solves most any foraging predicament. First, says Knight, "Correct identification is paramount. There are a handful of plants in our area that can make you very sick or even kill you if you ingest them. Learn these before you do any wild harvesting on your own! Good ones to know are: datura, poison ivy, poison hemlock, water hemlock, Texas mountain laurel, and oleander." Also, many edible wilds have nearly identical, but deadly, cousins. Take, for example, the honeysuckle I searched for as a child, Japanese honeysuckle (lonicera japonica). It's considered a weed by many, despite sweet nectar and delicious greenery. However, there are over 100 varieties of honeysuckle in the lonicera genus, and some will stop your heart if consumed. Even with the safe varieties, "unaccustomed foragers may take time to adapt to wild foods and medicines," so ease in to newfound foods slowly.

Oliverio adds the importance of knowing where you pick: "Be sure food you find in a public space hasn't been sprayed with herbicides and pesticides." Plus, this is Texas, y'all: "Make sure you have the right and/or permission to harvest any wild plants from an area," says Knight. Historically, and compared to California and Oregon, where lenient laws are currently ramping up controversy, Texas has relatively strict laws about foraging, dating back to the days of cowboys and barbed-wire fences. Foraging Texas, a Houston-based blog, offers four rules of foraging ethics that succinctly explain the legality and responsibility essential to harvesting from the wild. In short, it's all about respect: for the law, the land, the plant, and yourself. The technicalities of foraging are intricate, but basically, in Austin it is illegal to harvest from private property without permission. You can pick some edible items from public parks (provided you do not damage the plant), and if a fruit-bearing branch hangs over onto your side of the fence, it's fair game.

Again, though, simply asking permission is the best – and safest – route, and that increased communication among strangers is exactly what strengthens neighborhoods. Oliverio says, "Some people feel there's a stigma about 'scrounging' in other people's yards and are often afraid to ask. ... It kills me to see fruit rotting on the ground somewhere because the owner doesn't want to eat it and doesn't want to let others have it either. It's a shame."

The other possible hiccup in the adventures of foraging is related to concerns that some people, in some areas, may be harvesting to the point of ecological imbalance. (Think morels that sell for thousands, or abalone populations pushed to the brink of extinction.) Knight states, "The only thing I would like to stress though, is that we must forage responsibly. We live in a city with finite resources, and if everyone started harvesting as much wild food as they could, there would be major consequences for the ecosystem."

Ultimately, Knight says, "there is no substitute for learning firsthand from people who know what they're doing; herbalists, botanists, naturalists, and environmental educators have a wealth of knowledge and experience that will not be found in a book. ... It is very reassuring when you are physically with another human who eats a wild plant."

Would a Weed by Any Other Name Taste as Good?

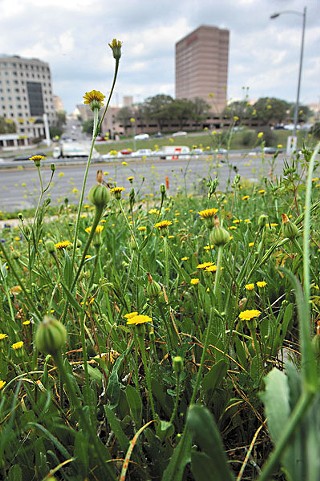

Now we know why, how, and where, but what exactly are these elusive treasure troves of tasty goodness? Well, weeds, mostly. The broad term includes pretty much any vegetation that is considered undesirable, for whatever reason (e.g., aesthetics, location), and many are considered a delicacy when growing in a different location or noticed by a different passerby. Consider the dandelion: mowed down or sprayed; picked without thought by children. Yet this flowering plant ranks as one of the highest sources of beta carotene. Oh, and it's delicious. Many backyards boast tons of edible weeds, says Knight, and "harvesting them would provide highly nutritional food for free and prevent the need or desire to spray harmful chemicals into the environment."

Fortunately for Central Texans, we live in a veritable cornucopia of edible wilds. Knight was enthusiastic to list some of his favorites, including many that are both abundant and easy to harvest: Turk's Cap fruits, loquats, acorns, wood sorrel ("Earth Native kids [have] taken to calling it the 'Skittles of the woods' for its pleasantly sour taste"), and hackberries.

Oliverio listed her citywide seasonal favorites as mulberries, figs, loquats, persimmons, plums, blackberries, peaches, pears, grapefruits, and the wide variety of leafy greens. She also cites making roasted tea from yaupon holly as a personal favorite, and mentioned that several of our Central Texas ornamentals are included in many Spanish horticulture books as excellent for food, tea, medicine, and topical remedies. And as a major bonus, because foraging requires reaching, squatting, walking, crawling, and other physical exertions, it is inevitable that bugs will be unearthed. Score! Foraged insects like grasshoppers, crickets, grubs, and caterpillars are becoming increasingly relevant in discussions of sustainable global food sources.

This slow-paced walk toward our ancestral roots offers a chance to knock on a neighbor's door, make a friend on the trail, or seek out recipes and mentors through social media, while enhancing and preserving food cultures. Becoming accustomed to celebrating the freshest possible food and sharing the bounty certainly opens eaters up to the possibility of culinary adventure. So, as a challenge for Earth Day 2014, on April 22, walk outside, find some food, and ask some questions.

Resources

Check these sites for upcoming classes and tours, as well as resources on foraging ethics and more.

Earth Native Wilderness School: www.earthnativeschool.com

Urban Patchwork Neighborhood Farms: www.urbanpatchwork.org

Mark Vorderbruggen, aka Merriwether: www.foragingtexas.com

The Useful Wild Plants Project: www.usefulwildplants.org

Green Deane: www.eattheweeds.com

Reference books are great for both identification and tips on gathering and processing your picks.

Wildflowers of the Texas Hill Country by Marshall Enquist

Trees, Shrubs, and Vines of the Texas Hill Country by Jan Wrede

Edible and Useful Plants of Texas and the Southwest by Delena Tull

The Forager's Harvest and Nature's Garden by Samuel Thayer

Foraging & Feasting: A Field Guide and Wild Food Cookbook by Dina Falconi

The Eat-a-Bug Cookbook, Revised: 40 Ways to Cook Crickets, Grasshoppers, Ants, Water Bugs, Spiders, Centipedes, and Their Kin by David George Gordon