A Place at the Long Table

The complex, nuanced, unmistakable taste of Juneteenth, 139 years later

By Toni Tipton-Martin, Fri., June 17, 2005

Tourists snap photographs. Health care providers offer cholesterol and blood-pressure screening. Insurance companies check car-seat safety. Corporate sponsors pass out free goodie bags brimming with logo-emblazoned brochures, pencils, flashlights, Frisbees, visors, and discount coupons. Vendor booths hawk everything from smoked turkey legs to purses made from kente cloth.

As I wheeled my picnic basket full of black-eyed peas, roasted red peppers, cornmeal, tofu, and cookbooks through the merchant's pavilion, past the barbecue stands, and into the health and fitness exhibition area inside Givens Recreation Center, I rechecked my motives to remind myself what I was doing here. At first glance, such a commercialized landscape didn't at all capture the kindred spirit of the first Juneteenth celebration I expected to experience in Austin.

At the time, I was promoting my first cookbook, A Taste of Heritage: The New African-American Cuisine, and the way I saw it, African-American cooking was in jeopardy of being lost – like blacksmithing and other black artisan crafts associated with slavery and poverty. Food was an expected part of the Juneteenth celebration, an event organized to celebrate, preserve, and promote African-American history. What better way for me to share my passion for African-American culture and foodways than to brag on the relative status of the plantation cook, and to share my belief in the truism "you can't know where you are going until you know where you've been."

Freedom profoundly influences the choices (yes, even the food choices) we make every day, I told the audience, quoting the work of Charles A. Taylor. Taylor is one of a handful of scholars who expands the notion of freedom beyond the search for lost loved ones and economic opportunities to include pursuit of important family values and kinship in his book, Juneteenth: A Celebration of Freedom, when he writes:

Freedom meant far more than the right to travel freely. It meant the right to name one's self, and many freedmen gave themselves new names. County courthouses were overcrowded as blacks also applied for licenses to legalize their marriages. Emancipation allowed ex-slaves the right to assemble and openly worship as they saw fit.

During the Juneteenth Expo that year, the audience heard motivational speeches from Debbye Turner, a CBS news correspondent and doctor of veterinary medicine who emphasized education; they attended self-improvement workshops; and I showed them ways to make a slave invention – African-American cuisine – fit into their busier, healthier lifestyles rather than discard it like spoiled milk. This was Emancipation Day in the new millennium. Newcomers to the region might find it difficult to believe, but the traditional historic threads of the first Texas Emancipation Day celebrations were indeed woven within the rich tapestry of the Miss Juneteenth talent show, gospel concert, fine arts festival, beauty pageant, battle of the bands, and, yes, even in the empowerment seminars on health and fitness.

Anyone who makes the effort to carefully consider the mélange of elements and look beyond the fence surrounding Rosewood Park (the heart and soul of Austin's Juneteenth), past the corporate banners and festival fare, will recognize the familiar American virtues of gratitude and pride much in evidence when families commemorate independence on Cinco de Mayo and the Fourth of July, and see a vibrant, thriving Juneteenth culture. It is difficult and painful through the prism of contemporary living, with its high tech conveniences and modern-day liberties, to recall and comprehend what life must have been like for enslaved black people, but the overarching intent of Juneteenth requires that we try. Freedom certainly didn't mark the beginning of family values for African-Americans, but the self-respect and dignity that came with the ability to manage even the most mundane aspects of life definitely helped them to flourish.

Upon deeper consideration, the image of teenage girls as they dance and shout to the heart-pumping drumbeat of dueling bands reverberating through the neighborhood surrounding Nelson Field reflects present-day tradition: a contemporary picture of the spontaneous reaction of slaves who shrieked, prayed, and sang as Union soldiers brought news of their freedom to Galveston Bay, on June 19, 1865.

On that day, Gen. Gordon Granger brought an end to the system that had forced them into the backbreaking labor that built this country's railroads and cities, tended its crops, cooked its meals, and nurtured its children when he read General Order Number 3:

The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and free laborer.

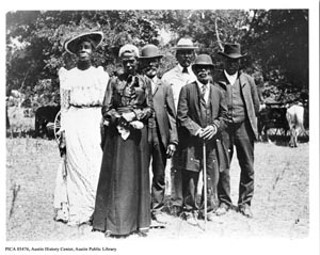

The first Freedom Day was held in 1866 as the newly freed, taking cues from the myriad celebration ceremonies they witnessed among the planter class, congregated in acknowledgement of the anniversary of their liberty. They arrived on farm vehicles and horseback and dressed in their finest clothes. The children played games together, and everyone listened attentively as preachers and orators recited special prayers and lectured against idleness and on the topics of business and education. The women brought favorite family dishes to share. The men barbecued. "Eating high on the hog" was not just a tradition; it was a ritual, according to this account, discovered by author and scholar William H. Wiggins Jr.:

The dinner was free. And you got all you want to eat. You know how they used to bring those long, long tables, they had rows and rows of long, long tables and then they had waitresses. The young men served as waiters and the young ladies were grouped locally in a circle. And they would go down and ... they'd have these trays, these big, large trays, and set the tables. And when they got the tables set they would call the people to dinner.

The reverential mood was not lost on the mainstream press, which seemed a bit confused by the behavior of the folks they had, until recently, depicted as "savages." Despite pre-Civil War attitudes against slaves, the Union, and Emancipation, the media carried constructive reports of "colored picnics" among the regular news features as well as advertisements for "Sunday best" shoes and apparel and "big red ripe" watermelons and this one, for Mrs. Baird's bread, also unearthed by Wiggins:

For Emancipation Day Parties and Picnics ... [serve] MRS. BAIRD'S BREAD. Mrs. Baird's bread, baked in the South's newest, most modern bread plant, tastes better because it's made right by Mrs. Baird's special slow-baking process. It's just the thing for sandwiches and it goes mighty fine with barbecue. ... When planning your Emancipation Day picnics and parties, don't forget to ask your grocer for Mrs. Baird's Bread. ... You'll like it better.

In 1869, the Daily Austin Republican described the "amazing sight" of black ex-slaves and ex-masters commingled in a barbecue celebration: "There was not a trace of unkindness visible in people's faces or in words uttered when the splendidly equipped colored military company moved to martial music through the streets."

From the very beginning, praying, preaching, playing, singing, storytelling, and eating were Juneteenth canons, but within a very short time, as blacks moved away from the city, the program lineup expanded to draw an assortment of interests. By 1900, the Austin community had split its festivities. "Unioners," who had served in or otherwise supported the Union army, celebrated June 19 at Wheeler's Grove, while former slaves who saw Juneteenth as the way to honor their ancestors and thank the Lord for the victory remembered at Govalle. Apparently, the ex-slaves didn't believe the "young folks" born after slavery appreciated Emancipation Day as much as they did.

Divisions of this sort persisted into the 20th century and probably gave way to the proprietary wrangling over venues and relevant activities that dog celebrations to this day. In 1904, feeling disillusioned and abandoned by institutions like the Freedmen's Bureau, which were set up to support and protect them, Juneteenth devotees took charge of the fight to establish official ceremonial grounds for June 19 activities. Evidence collected by Karen Riles at the Austin History Center reveals the pioneering spirit of the Emancipation Organization of Travis County, led by Thomas J. White, which purchased five acres of land on Rosewood Avenue, and named the location Emancipation Park. A year later, the celebration scene enlarged with the addition of a 3-acre site near Walnut and East 12th.

William Kerley, a retired postal worked raised in Hutto, who was a member of the Emancipation Celebration Association, recalled the grand-scale festivities and some of the early food traditions that epitomized Juneteenth celebrations in Emancipation Park at the turn of the century.

"We used to really look forward to that day," Kerley told an Austin American-Statesman reporter in 1975. "We used to dig a big hole in the ground, put wood in it and cover it with iron pipes and wire. That was our barbecue pit. The whole town used to come out to the park, including plenty of whites. ... In fact, many of the white merchants furnished food and money for the picnic."

And why not? An unexpected outcome of the merriment among Austin's black population was the impact on its white-owned business community. According to newspaper reports, manufacturing in city plants came to a screeching halt and local businesses closed the doors for the day because "the Negro laborers were all celebrating forcing whites to take the day off too."

Rozena Hoard, a 99-year-old woman whose life story was captured by the Federal Writers' Project, also recalled the camaraderie and homecoming spirit of the early days with "folks arriving by wagon with tubs of food served on makeshift tables [planks of lumber] spread with red tablecloths. Everyone shared."

Virgie Collins Garrett, a retired guidance counselor and teacher whose family celebrated Juneteenth at their homestead in Littie, Texas, then trekked by the carload to Austin to attend the ceremonies in Rosewood Park, has vivid memories of the pre-civil rights years.

"My family believed in celebrating every year," says Garrett, a descendant of the Collins clan, one of the noted black families featured in an exhibit at George Washington Carver Museum. "Friends with large families came out and ate with us. My mother and her friends would cook all morning."

Despite such deeply rooted tradition, the rigors of sharecropping, Jim Crow segregation, lynching, social and civil unfairness by angry white Americans eventually took its toll on the annual freedom celebration. In the post-World War II years, a confluence of events began to push Juneteenth into the background. The trend started with the violent murders of Emmett Till and four little girls in a Birmingham, Ala., church, and gained momentum as students and nonviolent protesters campaigned for the right to eat in restaurants, ride on city buses, and vote in elections. It culminated in the notion, described by Ada Simond, a newspaper columnist with a long history of involvement in black heritage projects in Travis County, that integration meant it was "bad to speak about slavery." Austin families adjusted their priorities, joined the Direct Action campaign against segregation, and forgot about Juneteenth.

J. Mason Brewer, chair of the Division of Language and Literature at Huston-Tillotson, longed for the "huge fish fries where the old folks were fed first." He captured the disheartened outlook in an eight-stanza poem (captured in part here) titled "No More Juneteenth Like It Used to Be":

Ain't no more "Juneteenth"

Like it used to be;

When Abe Lincoln writ a letter

Settin all the black folks free.

Ain't no more big picnics,

By the riverside,

Where we sung 'Swing Low Sweet Chariot'

'Til we all broke down an' cried.

A few celebrants managed to hold small-scale events throughout the civil rights era, despite headlines that loudly proclaimed "Juneteenth Is Dead." Eventually, those years between the sit-ins of the movement and the Voting Rights Act spawned a commanding race pride that reinvigorated Juneteenth festivities. By 1975, the same authorities that had eulogized Juneteenth in Austin now cheered its "comeback," which was propelled by nostalgia for family bonding nurtured on the eve of the "big day" while tending hot barbecue coals, churning the ice cream freezer, frying crisp chicken and fish, and baking enough pies and cakes to fill a bakery. In the minds of Austin's older generation, Juneteenth was more than tradition, it was requisite – like asking who cooked the greens or made the potato salad before you ate any of it.

A few short years later, however, in part because of improving social conditions and a rising middle class, a new paradigm of black consciousness emerged among the younger, more educated folks who wore Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man like a badge of honor. It was perhaps inevitable that post-civil rights children, eager to shed the underclass images that dogged their parents and grandparents, would lose their appetites for elements that they believed no longer represented them. Watermelon, a Juneteenth staple universally beloved as the icon of cool summer refreshment but disdained among the black community's upwardly mobile as a remnant of minstrel-era stereotypes, was among the casualties.

Then, along came State Rep. Al Edwards. In 1979, during his first year at the Capitol, he scratched and clawed to pass House Bill 1016: legislation that established June 19 as a legal state holiday. According to his Web site, he also formed Juneteenth USA, a nonprofit organization he hoped would grow Texas into a state that "embraces all." The group focused its efforts on exposing youth to the June 19 story and supported the development of Juneteenth organizations throughout Texas, the nation, and abroad by its endorsement of annual celebration events for the community at large.

Observances exploded. In addition to the preaching, praying, and praising that characterized original celebrations, neighborhood commemorative activities mushroomed to include baseball, basketball, tennis, golf and card tournaments, political receptions, children's programs, seminars, free concerts, fireworks, and parades. Chittlins went back on the menu, along with barbecue beef, sausage, black beans, corn bread, "soul" burgers, red soda water; watermelon even surfaced on the list of iconic African-American food traditions. Spectators were struck by the large assortment of "good food." An area teenager told interviewers that Juneteenth was "a good chance to come out and eat some barbecue."

Since that time, despite a highly transient population and urban sprawl, Juneteenth in Austin has been known as a weeklong pursuit with multiple organizers.Event planners say this year's celebrations will keep an eye on tradition, but will appeal to a broad, multicultural audience as they attempt to stay relevant.

The activities at historic Rosewood Park, for instance, will be guided by the theme "Embrace the 21st Century – Celebrate 14 Decades of Freedom" and will include a kickoff dance and auction at Doris Miller auditorium; the Rosewood parade, featuring government officials, area churches, clubs, families, businesses, and marching bands; and a community program featuring a commemorative ceremony to honor the late Donald Spence, gospel singing, praise dancing, contemporary singing, creative movement, arts and crafts, vendors, information booths, a carnival with rides, and live musical entertainment. Gospel Fest Explosion, featuring praise dancers, solo artists, Christian drill teams, and a gospel concert culminates the celebration on June 19 at the AISD Delco Center.

The Carver Branch Museum and Cultural Center will augment its core Juneteenth exhibit, which highlights the people, activities, and traditions associated with local celebrations, along with several days of activities. Among other capital city Juneteenth activities are the Congress Avenue Parade, the Oxygen Freedom Run and Walk, the third annual Tyrone Johnson Basketball Showcase, and the second annual Alvin Patterson Battle of the Bands and Drumline Competition.

By the time the gates at Nelson Field swing open, and dusk and a cooling breeze finally settle over the sweltering crowd gathered in the Northeast Austin grandstands for the battle of the bands competition, there will be a crescendo of delicious memories of remembrance, reverence, and revelry as locals and visitors alike reflect on what it means to be free.

To embrace the reminders of slavery and poverty – including the gastronomic vestiges like red soda water, watermelon, catfish, barbecue, and the sweet treats of childhood – can be hard, but to do so is to honor the suffering and affirm the contributions made by generations of freed African-Americans. When nurse practitioners explain ways to be in good health, Juneteenth attendees will understand what it is like to no longer be subjected to inspections of one's body or home; the job fair will make them appreciate the opportunity and the decision to get an education; and merchants hawking African garb will help partakers value the right to choose how they dress. And, with any luck, the families who share a homemade picnic in the park will recall the artistic spirit and selfless determination of generations of African-American cooks who were finally able to decide how they would prepare vegetables and set the time and manner in which the family ate its suppers; they can cheer the restaurateurs who for so long were denied the opportunity to serve.

"We all ought to rejoice in the positive celebration of what this holiday represents," says Wilhelmina Delco, a dedicated leader, committed community activist, and former Juneteenth speaker. "But every time we celebrate Juneteenth it is a reminder that there are still obstacles to our full participation in the American dream." ![]()

Toni Tipton-Martin is a past president of the Southern Foodways Alliance (www.southernfoodways.com), and she was food editor of the Plain Dealer in Cleveland before moving to Austin, where she lives with her husband and sons. Her next book, The Blue Grass Cook Book, a historic reprint of a recipe collection originally published in 1904, will be released by the University Press of Kentucky in October 2005.