First Round Draft Picks

The Live Oak Boys Go Pro

By Pableaux Johnson, Fri., Oct. 13, 2000

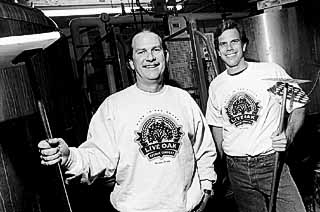

Chip McElroy and Bryan Peters are living every homebrewer's dream. Sure, it's a dream that requires hard work, lots of heavy lifting, and a bit of megalomania, but then, a dream's a dream. As owners, brewers, and distributors of Austin's Live Oak Brewing Company, the energetic pair have reached the highest level of malty geekdom. They are self-described "beer nerds gone pro."

In the seven years since its founding, the team's high-maintenance brainchild has garnered a stellar reputation among local bargoers and the international beer press. The pair brews everything from a complex Czech-style pilsner (Live Oak Pilz) to their Big Bark, a malty Vienna-style lager. During summertime, Peters and McElroy produce their refreshing Hefeweizen (Bavarian wheat beer), and autumn heralds the tapping of an Oaktoberfest varietal. But despite the wide range of well-regarded brews, Live Oak brews only 1,300 barrels of beer annually, and their distinctive oak-trunk tap handles can be seen only in the greater Austin area. (In the latest issue of the brewer's magazine All About Beer, brew scholar Michael Jackson compliments Live Oak on their pilsner's consistency and stylistic accuracy.)

The dream of "going pro" started with the pair's near-fanatical devotion to a single style of beer -- the authentic Bohemian Pilsner. McElroy, a UT microbiology grad student, got into homebrewing as an almost logical pastime. "Brewing is what microbiologists do -- basic enzymology and fermentation -- but in a real primitive way," he says. In the early Nineties, he met Peters (an electrical engineer by trade) at a local homebrewer's gathering and Peters mentioned an upcoming trip to Prague. "At the next meeting," Peters remembers, "Chip shows up with a stack of brewery coasters and recommendations."

In the following years, the two eventually brewed together and specialized in the complex, malty pilsners native to the Czech Republic's Bohemian region. "I was brewing on my little apartment stove," McElroy said, "and Brian had this huge gas restaurant stove -- so it made bigger batches a lot easier."

Just about the time they had hit on the right recipe, the Texas Legislature passed House Bill 1425 and gave the green light to brewpubs in Texas. Homebrewers all over the state considered a jump into large-scale production.

"There were a lot of SBA (Small Business Administration) loans all over the place at first," Peters remembers, "but by the time we got there, they had started to dry up." The pair drew up three different business plans -- one each for a brewpub, a full-scale microbrewery, and a more bare-bones micro -- and started shopping around for loans and investors. Eventually they secured enough funding to execute the least expensive plan, and a shoestring brewery was born.

The thing that sets Live Oak apart from many other microbreweries is its dedication to re-creating the traditional Czech pilsner using traditional methods. In an attempt to achieve the deep golden color and hoppy dryness of the original, McElroy and Peters dedicated themselves to a process called "decoction mashing" -- a labor-intensive, multistage boiling process that makes for smoother, more full-bodied lagers. A portion of the original mash (grain/water mixture) is siphoned from the main tank, heated to a boil, then mixed with the unheated mash.

"It's a lot more work," Peters adds. "There were people telling us that we'd burn out. They'd pull us aside and say, 'You know [dramatic pause] ... you don't have to do it like that.' Even the original breweries in the Czech Republic are phasing it out. The beer magazines are always writing about 'the death of decoction.' Except for us."

Decoction has been on the wane since modern technology has entered the brewhouse, and according to McElroy, "it's only appreciated and practiced by a handful of wackos in the U.S., but it's better for the beer's flavor and color. It really doesn't make monetary sense to do it our way, but we wanted to bring a real Czech-style pils to the market ... and we wanted to do it right."

The process of "doing it right" on a shoestring budget means focusing exclusively on a manageable core business -- local draft sales -- and foregoing expansion into the additional markets or the high-profile package market. "In order to put our stuff in bottles, we'd have to increase our output, install a bottling line, make room for the truckloads of six-pack holders." McElroy motions to an unused bottling line. "We'd love to have our beer in bottles, but then we'd have to pasteurize and take chances with the quality."

In the meantime, Live Oak works on a self-distributed "kegs-only" basis to accounts all over Austin. That means the same four employees responsible for running the brewing end of the business also have to deliver kegs, clean the lines, and maintain their own taps in bars across town.

"It's a tough business," says McElroy, who usually delivers to their 60 regular accounts, "and you have to compete for yourself on a retail level, but we're also going to sell our stuff a little better." The hands-on approach also helps Live Oak promote their local connections and personal touch everywhere their beer is served.

The brewery itself -- a renovated former meat packing plant on the Eastside -- employs a grand total of four workers (owners included) and reflects the resourceful do-it-yourself nature of its founders.

"When we moved in here, the place had been abandoned for about five years," Peters says, pointing to the enclosed fermentation room. "There were squatters living here, making campfires inside. It was a mess." He and McElroy dug in and enlisted the help of friends. Double-paned safety doors came from the nearby Habitat for Humanity annex.

After the initial investment, they didn't have the money to hire employees to construct everything that needed to be done, so they essentially hand-built the operation from the ground up -- improvising and adapting as they went along. Equipment came from industrial auctions and bankruptcy sales. Huge stainless steel tanks purchased at dairy auctions became fermentation vessels. Corn augers from an old tortilla chip plant now grind the barley required for beer production. A tour of the plant includes offhand tales of the machinery's past lives -- thousand gallon storage tanks from Canada, pumps from defunct San Antonio breweries, kegs from a failed micro in Waco.

"This we got from Lone Star down in San Antonio," Peters says as he shows off a wheeled pump the size of a large retriever. "It's amazing. This thing will pump oatmeal all day -- and it makes the decoction a lot easier. It's worth about seven grand new, and we got it in a bidding war -- for 75 bucks."

And because of their bare-bones approach, Peters and McElroy survived two major business milestones in the microbrew business. "It's usually three years to break even and five years to get your brand known," says Peters, "And a lot of micros who started didn't make it."

After seven years and tons of positive press, Live Oak may not be knocking down Sam Adams' door, but they're doing just fine. In December, they'll debut the fifth beer in their arsenal -- an intense IPA (India Pale Ale) called Liberation Ale to replace a previous seasonal brew, Liberator Doppelbock.

"Yeah, we're still trying to decide on the hops for the Liberation," Peters says almost extemporaneously. Within seconds, he and McElroy are knee-deep in a discussion of the merits and characteristics of different hops, including the "noble" varieties and "higher alpha acid Cascade derivatives," all while kicking back with a glass of their own brew.

Clearly, some people were cut out for the pros.![]()

Chip McElroy and Brian Peters will host an Oktoberfest Celebration in conjunction with the Central Market Cooking School at the brewery on Sunday, Oct. 22, from 3:30-5:30pm. There will be a brewery tour and beer tasting, plus food prepared by CM chef Paul Schunder. Call the Cooking School at 458-3068 for reservations.