Slippery Slope

To water-park jefe, Schlitterbahn's Jeff Henry, whimsical salvage is no mere whim

By Kate X Messer, Fri., May 16, 2014

"This is the fun part of my job," says Jeff Henry, principal and co-owner of Schlitterbahn Water Parks, as he thumbs through a ream of 8.5-by-14 sheets an inch and a half deep. The hefty doc looks like the opposite of fun and more like a last-minute exam cram. It is, in fact, an old prospectus loaded with specs, pictures, and data of an oil rig built in 1969 and currently for sale as salvage – all 20,000 tons of it.

"I get to go through stuff like this. I sit up until 5am, start reading, and can't put it down."

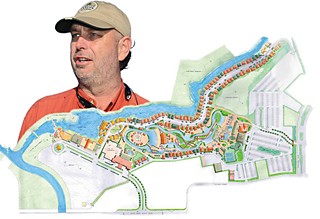

Henry, an award-winning inventor and water-park magnate, has implemented, designed, or somehow had his hands in the gushing stream of water-park technology for over three decades. He holds over 60 patents on some seriously splooshy technology. Whether he was the brains, the brawn, or the funding, his foresight exponentially advanced an industry that now has tech standards like the Master Blaster uphill watercoaster; the Boogie Bahn FlowRider surf simulator; the AquaVeyer guest conveyor belt (which utilizes a giant, bright blue Archimedes' screw to churn water to propel the thing); the Transportainment system of guest traffic management; and the bedrock of the industry: filtration, circulation, and reclamation systems to conserve that precious commodity, water, to look up to. Henry and his merry band of equally eccentric engineers and brainiacs have left distinct footprints, visible, not only in the domestic Schlitter-family of parks across Texas and in Kansas, but in destinations across the planet like the world-renowned Atlantis mega-resorts in the Bahamas and Dubai.

He flips through his phone's photo gallery like a giddy kid showing off a shelf full of freshly built Lego kits: "I might be able to save that ship ... I really want to buy that one ... There's a piece we put on a barge ...." Except these are pictures of mammoth structures – like this oil rig, those ships, that marine crane, a couple of 80-foot bridges, and 700,000 pounds of chain – which will be transformed into ridiculously fun set-pieces, structures, and rides at Schlitterbahn.

"When I get a piece of massive structure like that, guess what I get to do?" he asks with wild eyes and an endearingly dopey grin. "I get to dream bigger."

Jeff Henry's been dreaming big since the early days when parents Bob and Billye bought the Landa Resort on the Comal River in New Braunfels and began to develop what is now Schlitterbahn (a word which loosely translates from German into "slippery road," for those of you who've been living under a felsen). "I started out buying inner tubes for a quarter at gas stations and renting them out. From that, I built a tube chute so I could charge more money. That's really what got me going."

He then begins to describe his work history and work ethic – a circuitous voyage which sounds and feels, not surprisingly, like a ride on the Master Blaster: "I don't have a job, I have a lifestyle. I get up in the morning and go 'til I drop. I've been a short-order cook, a bottle-washer. I've been a janitor, I've done laundry, I've stripped rooms and remade them. I've done every job that there is, pretty much."

"Applied materials technologist" is how Henry punningly refers to his role and skill set. "I apply used materials that I find – some people call it junk; some people call it trash; I call it found art. I'm really good at ripping up something, figuring out how to use it, and applying it to the amusement business I grew up in. It's second nature to me. I like it. It's fun. I like reusing materials more than using new materials."

What many visitors may not realize upon entering a Schlitterbahn water park, is that much of the ingenuity on display is recycled from something else. The original New Braunfels flagship was carved out of two previous relaxation destinations: Landa Resort and Camp Warnecke. And recent remodels and renovations, including the new resort on South Padre Island, the luxurious Treehaus suites in New Braunfels, and the upcoming park slated to open this summer in Corpus Christi, employ chunks of ship salvage, retired hotels, old theme-park parts, and scores of timber reclaimed from the devastating 2011 Bastrop County wildfires.

At Schlitterbahn, sustainability may create whimsy, but it's no mere whim. So please don't say "greenwash" to these folks. They've been walking the walk since their earliest days along the Comal. Repurposing decommissioned and deconstructed items can be quite time-consuming and is not cheap. Henry's peers in the industry – a business that survives on the newest, brightest, shiniest, latest, greatest tech – might bray at that high cost to ready salvage for reuse.

"They're probably right," he acknowledges with frustration. "But there's something really wrong with a society that doesn't reuse things that are reusable. There's something really wrong when labor rates are so high that you can't afford to pull nails, so you grind up perfectly good two-by-fours and cut down perfectly healthy trees in order to drive up a model of life that is based on consumption rather than based on sustainability."

Adena Lewis, tourism coordinator for Bastrop County is pretty bowled over by Henry's offer of new life to felled trees amidst the unthinkable loss experienced by her hometown, after the most destructive wildfire in Texas history wiped out more than 32,000 acres, much of which was populated with the beloved loblolly pine. Escaping a fate as ground-up mulch, the forest has risen again as rough-hewn decorative siding, smooth decking, and imposingly sturdy furniture at all of the water parks. The South Padre resort even features an event space called "The Bastrop Room" and a pizza cafe named the "Loblolly Grill."

"Schlitterbahn initiated this project from their heart, and it has touched the heart of Bastrop County," says Lewis. "It was all their idea. To see a continuing value and use of the trees of Bastrop County to bring joy and happiness is an additional way to help us heal."

Henry's Schlitterbahn Development Group is an industry leader, no doubt. A quick click of the remote to tune into any of the Travel Channel's top-water-parks shows always includes the Texas-grown attraction. The adrenal rush and cutting-edge tech of new crazy rides surely contribute to this. But what Schlitterbahn has over other water-park chains is that they remain a family business. To their core.

In the early Nineties, Henry and potential competitor, California surfer-turned-inventor Tom Lochtefeld met at an industry conference and decided, instead of coming to loggerheads, to come together to create the first FlowRider. Central Texans know it better as Schlitterbahn's Boogie Bahn, a 50,000-gallon-per-minute whoosh of human-made wave, the world's first surfing ride – a big, puffy sideways half-pipe covered in soft, blue foam, and a constant flush of water. "Tom did all the development, and Jeff funded it, took a leap of faith, and was integral in getting it off the ground," according to Lochtefeld's son, Ranney. "Jeff is an incredibly creative guy, always looking to do new stuff." A similar technology drove the pair's next collaboration: the Master Blaster uphill surf coaster. "My dad did the prototyping, and Jeff did the full development and handled sales," says the younger Lochtefeld. The pair's technological offspring arguably launched the inland surf movement that's currently making waves in the trade.

This year, Schlitterbahn celebrates 35 years in the entertainment industry – not with specially marketed swag, not with bells, whistles, nor fireworks displays, but with continued free parking, free inner-tube use, and the freedom to bring in your own picnic basket (leave the glass bottles, jars, and Uncle Ed's flask at home, please). Radical for a company within an industry hot to squeeze every last drop of point-of-purchase impulse out of every pair of board shorts.

"Schlitterbahn has a repeat business," says Henry. "People come back because there are memories built on good times in the Hill Country or on the beach. Our goal is to bring an integrated experience to people, a place where they can bond and be together and build these lasting memories. There's a lot of competition for people's time, but not much competition for things that people can do together," he insists.

And when you're in the business of nostalgia, comfortable worn-in objects, familiar adventure themes, and "found art" begin to make a lot of sense.

Meanwhile, Jeff Henry and the Schlittercrew are prepping for an epic summer. The season has just begun for the four parks in New Braunfels, Galveston, South Padre, and Kansas City, and the one farthest north has a new sight on the horizon. The KC park team is unveiling the world's tallest waterslide, Verrückt (confirmed with an official Guinness World Record ceremony), and down south, a team captained by Henry is polishing up the new park in Corpus Christi for her debut later this summer.

Now, if he could only figure out where to stick this 20,000-ton oil rig ....

See more online on our Summer Fun page: austinchronicle.com/summer-fun.