Chapter 4: The Nineties!

March 1991 -- December 2000

Fri., Sept. 7, 2001

Austin: The recovery blossoms into the second boom. The first half of the Nineties is growth, but the second half is explosion. The town grows into a city and then into a big city, known to people worldwide. The Manor airport dies a natural death, but the Bergstrom option saves the day. Austin finally breaks ground on a City Hall, but only after giving away five blocks of downtown to a software company. The Convention Center opens, becomes home to SXSW, then grows. Capital Metro tries, then stops trying, then tries, then stops trying, then tries again to approve a light rail system, to be stopped by fewer than 2,000 votes. Enviros pass the Save Our Springs Ordinance overwhelmingly, see it thrown out, then reinstated, then (for the most part) superseded by the courts and the Legislature, even as the Chamber and the progressive community smoke the peace pipe and elect Kirk Watson mayor in 1997. By 2000 the population is 642,994 and close to twice th`at in the greater Austin area.

Chronicle History: The building is set on fire in March1991. We become Beirut-like. In August, we move into the Elgin Butler Brick Company building at the corner of 40th and I-35. How appropriate. To pound on the walls is to realize the building is an above-ground nuclear bunker; it could take a direct hit from an atomic warhead and the arctic blast of the air-conditioner might shudder momentarily if at all. It's here, through the Nineties, that the Chronicle finally settles into stability, respectability. At the beginning of the decade, the issue size is roughly 60 pages, and those pages are still being laid out on light tables, editors often cutting their own copy and trying to squeeze as many gray words into an editorial hole straining against its still-modest ad ratio. By 2000, after years of keeping pace with the red-eyed bull economy of the Nineties, the issues are approximately 160 pages, and the paper has grown to the point where readers complain about not possibly being able to read it all week in, week out. Pagination, meanwhile -- transmitting the paper to the printer electronically -- is on the horizon, having debuted during the paper's daily SXSW supplements in March 2000.

Chronicle Content: The quality level hits a certain consistency; Marjorie Baumgarten, Robert Faires, Margaret Moser, as writers and editors, lead the decade-long charge. The growing influence of the advocacy journalism of Daryl Slusher and Robert Bryce, and then Mike Clark-Madison (who brought a neighborhood-oriented sensibility), finally erase the definition of the Chronicle as simply a music and entertainment publication.

Roland Swenson

SXSW '91 was the most difficult year yet. It was the only year we were unable to book dates during Spring Break at the Hyatt downtown. Suddenly, with all the students in town, nightclubs were quickly filling to capacity, and for the first time, the Fire Department took to the streets closing down clubs, leaving people waiting in long lines. This had never been a problem before, and we didn't have any plan in place to deal with these circumstances. People were furious. On Monday morning after the conference, the American-Statesman blasted us for our incompetence and questioned our ethics.

That afternoon, we unloaded everything from the conference back into the office. Truly depressed and exhausted, I left to go home for the first full night's sleep in many weeks. Around 2am, my phone started ringing and kept ringing until I dragged myself out of bed to answer. An excited Michael Corcoran was on the line telling me the SXSW office was on fire and I had to get there right away because he couldn't reach anyone else.

When I got to the office, it was like a scene from a movie. The entire area was bathed in an eerie color with white spotlights and red flashers. The parking lot was filled with fire trucks, and firemen were dragging hoses everywhere. Relieved that I'd shown up instead of going back to bed, Corcoran took me to see the lieutenant in charge of arson investigations. The lieutenant looked like Steve McQueen in The Towering Inferno, his face smudged with smoke, wearing his fire hat and gear. He leaned close and fixed his gaze on me, asking in a solemn tone, "Do you have any enemies?"

The response time of the Fire Department was so short that the blaze was extinguished just before it reached the roof of the two-story building, or everything would have been lost. According to investigators, someone had taken several stacks of Chronicles, wadded them up next to the wall, and lit them. The next day we sorted through the mess in the Chronicle and SXSW offices that were thick with smoke and water damage. Despite compiling a list of suspects that was frightening to consider, we never learned who set the fire.

The property owner evicted us in order to gut and remodel the building with proceeds from the fire insurance. The search was on again for a new home for the Chronicle, now complicated by the need for adjacent space for SXSW's growing staff. After months of working in the smoke-damaged rooms, the Chronicle found and bought the old Elgin Butler Brick Company site at 40th and I-35. The tract of land included a small brick house a block up from the Chronicle, where SXSW set up offices.

Doug St. Ament

I had moved to Austin with a fine arts degree, which basically opened a lot of doors to jobs in the restaurant business. I had been managing a pizza restaurant when I decided to ditch all that and pursue a career in applied arts. So I went back to school.

My graphic arts teacher got a call from the Chronicle's art director, Martha Grenon, saying she really needed two production folks in a hurry because the two regular folks were about to leave on vacation and they had neglected to get temporary substitutes. I went down with one of my classmates the next day.

She (the classmate) walked in and said, "This is one of the most disgusting places I have ever been." I walked in and said, "This place is awesome." We got the crash course in what to do. We also heard this story from someone about how we should have been there the day before because there were maggots coming out of the ceiling due to a mishap with the air conditioner's drip pan. My classmate left and never came back. I stayed on for the full two-week assignment. When I left, I told Grenon if they ever had a permanent opening to let me know. Three months later I got a phone call.

I remember the day they held the Belton Finders Day Festival in the parking lot. They were re-enacting the day Nick and Susan found Belton the dog near Lake Belton and rescued him. Then there was the time that someone tried to light a bunch of papers on fire and almost burned the building down.

When we moved to the new office, I borrowed my girlfriend Sarah's pickup truck and was part of the crew to move the production department. We packed the light table in the back and used old issues of the Chronicle to cushion it. Herb Steiner took one look at our setup and warned us it was trouble waiting to happen. We set off, and only a few blocks away, in front of Milto's, the light table fell out of the truck, slid through the intersection, and broke into millions of pieces. I got out of the truck to clear it out, slid on a piece of broken glass, and sliced up my leg. I think The Daily Texan ran a story the next day about how there was a whole bunch of broken glass at the corner of 29th and Guadalupe, but its origin was unknown. Anyway, Tim Grisham ended up driving me to Brackenridge, going down I-35, and all those newspapers we had used to cushion the light table went flying out all over the interstate. Jackie Potts (the production mom) later put up a sign that said "Chronicle Safe Moving Days: 0."

Margaret Moser

I moved to paradise October 1988 and thought my life was over. But in June 1991, I moved back from Honolulu to Austin. Two years of editing tourist magazines on the islands allowed me to grease my way back into the Chronicle with a variety of editorial skills the paper was just beginning to need. If it looked like little had changed in the offices on 28th Street since I left, they would change drastically as we moved to 40th Street that summer.

Nick and Louis bought the building that was the former Elgin Butler Brick building. The 25-30 people who made up the staff delighted in its long hallways (perfect for sliding in your socks!), its (then) many rooms, the separate bathrooms (plus two other toilets!), and most of all, the huge yard out back with trees.

S. Emerson Moffat

In 1991, the Chronicle makes the leap to office ownership, buying the former Elgin Butler Brick building at 40th and I-35. During the move, a production light table tips overboard en route, leaving what The Daily Texan describes as "mysterious wreckage" at the corner of 29th and Guadalupe. Production department stalwarts Tim Grisham and Doug St. Ament deny all knowledge. The new building comes with a grassy field between the Chronicle and SXSW, ready-made for volleyball, and a family of possums that set off the burglar alarms nightly. Staff morale is definitely up.

Suzy Banks

I'd heard rumors that Louis could be a, um, curmudgeon at times. I'd never seen his dark side firsthand, mind you, since I hardly ever went to the office, mailing all my stories instead (pre-e-mail, for you youngsters).

Then I was invited to a Chronicle Christmas party at the old Antone's on Guadalupe. I dropped the shield of mystery I'd honed and set off to get tipsy with my unknown co-workers. At the start of the already raucous party, I found myself standing next to Louis. I hugged him and thanked him for inviting me. He didn't hug back. "I didn't invite you," he said. "This party wasn't my idea." He walked off without even looking at me. I was crushed. My husband and I went to another bar, where I drank margaritas until I barfed.

Since I'd seen the beast and lived to tell the tale, I started dropping by the office more and more. Despite the passing years, time never mellowed my nervousness when I ran into Louis in the narrow hall, but ever after, he was sweet to me (yes, sweet) and always encouraging.

I dream about someday writing an important book. I haven't even started it, but I have the dedication page written: "To Louis Black -- it's his fault I never gave up."

Spike Gillespie

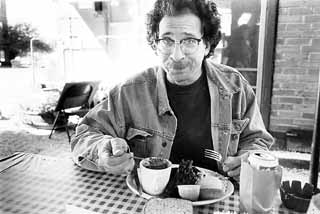

September 1991. I'm standing, twentysomething, hopeful, fearful, barefoot, in the offices of The Austin Chronicle. I'm clutching a handful of my meager clips, articles from hifalutin magazines like Veterinary Practice Management. I've been in Austin maybe two weeks.

In the Vaseline-smeared lens version of my Chronicle movie, it goes like this: I ask to see one Louis Black -- sans appointment. I'm denied. Looking up, I spot him. How do I know it's him? I just do. I leap (lunge? fly? vault?) past the front desk, cram my writing into his hands, and mumble introduction. Then I dash back out to car. Maybe that's when it starts raining. It does start raining. Because it has to be like a movie. Because Louis is involved.

The very next day, he calls me. I have no idea yet that a call back from Louis -- a prompt, friendly conversation -- is about as common as getting a call from Queen Elizabeth. "This is Louis Black," he says. "I like your writing." He says I can write for the Chronicle. "Thank you!" I gush. I feel like Miss America. Thankyouthankyouthankyou!

My first assignment is a profile of Turk Pipkin and his Full Moon Review. I go on to cover a quartet of red-headed performance artists and their weekly installments at the Candy Factory. I elbow my way up to the comedy beat.

Louisa C. Brinsmade

It was 1992, the beginning of the latest economic boom in Austin, and I was about two hours old at the Chronicle as the new assistant Politics editor. The job consisted of working with Politics Editor Daryl Slusher, who was writing a weekly political gossip column by Al L. Ears and editing Alice Wightman in "Council Watch," Robert Bryce in "Environs," and Roseana Auten on AISD board meetings.

Austin wasn't a sophisticated city then. At every philosophical crisis, the whole of City Hall seemed to stumble out into the bright lights, blinking, despite the fact that the battle lines were so easily defined: East Austin vs. the Tank Farms; Jim Bob Moffett/Gary Bradley vs. SOS.

It seemed a miracle SOS had passed in a citywide vote, but the cheering was abated by the flurry of lawsuits filed against the city by irate developers. No matter, good had won over bad, and the lines were clear.

In fact, nothing could be clearer than a photo by Alan Pogue that hung behind Daryl's desk -- a shot of Gary Bradley emerging from another successful snowing of the Planning Commissioners wearing a dark suit, dark tie, dark grin. The handwritten caption read: "Look into the darkness long enough, and the darkness will look into you."

Gerald McLeod

The first Macintosh the Chronicle got was a second-hand Mac II around 1992. I remember thinking, "This is cool, but it will never replace the X-acto knife and stat camera." The best thing about it was playing Tetris and Mahjongg. Now the paper is put together almost entirely using Macs, and the interns using them don't know what an X-acto knife or stat camera are.

Margaret Moser

Marjorie Baumgarten and I became officemates in 1991 and stayed that way until they sent me home to write full time in 1999. We were like dragons at the gate, the guidance counselors at high school you'd rather face as opposed to the principal and vice-principal, Nick and Louis. We worked as a tag team of sorts, editing, proofreading, putting together the annual Musician's Register.

It was the early days of computers, and one night Marge was making noises over something. "What's wrong?" I asked. "I hate spellcheck," she grumbled. "It changes words around!" I walked over to look at the screen. It took only a second to respond and duck. "Are you sure you don't just have Irritable Vowel Syndrome?"

Andy 'Coach' Cotton

The experience of a one-man sports department in a publication where the fundamental focus is politics and music isn't always fun. The issue isn't, as you might think, that the Chronicle's a weekly, and thus playing second fiddle to a daily that by nature is more up to the minute with numbers, standings, and whatnot.

Rather, it's a matter of priorities and allocation of resources. Chronicle political writers are taken seriously in the corridors of power; Amy Smith's calls to Kirk Watson and Lloyd Doggett are returned, requests for interviews considered, appropriate access granted. The Chronicle's a player in arenas of far more substance than, say, my access to a football game against Texas Tech. Since Nick and Louis feel I cover whatever "sports" needs the Chronicle requires, I sit as a sports department of one.

I clearly remember my first column, in April '92. It was, I thought at the time, a hard-hitting piece on Tom Penders, then embroiled in a petty, prophetic tale concerning an assistant coach stealing lunch money from players. There was no mention of my dogs, dating habits, children, or vices. Hot damn, I was a sportswriter! Not so fast: I quickly learned, as did my predecessors as Chronicle sports chiefs (Big Boy Medlin and Michael Corcoran), that a highly personalized column -- where sports are only part of the column's life -- is a necessity if you plan on surviving 49 weeks a year. This is where a serious lack of editorial interest has its advantages.

For one, I can say almost anything, insulting any person, organization, or nation without fear of being redlined by an editor. I have no idea if John Mackovic, Rick Barnes, or Mack Brown even know I exist, let alone care about what I say. I've learned I can be creative in making something entertaining out of virtually nothing. I've learned I can't outdo the mainstream media, but I can be effective as a guerrilla writer, sniping at people from behind a stone wall. Who cares if they don't know they've been hit! I never cared much for that freezing-cold stuffy UT press box anyhow.

Spike Gillespie

Besides covering comedy, along the way, I started submitting personal essays. Louis and his editors published them. Soon, confidence building, voice strengthening, I submit more -- to the Chronicle, to other places. I learn how to extol on depression, alcoholism, domestic violence, and child abuse. I also explore lighter things: traffic tickets, Playboy centerfolds, my short-lived stint as an Internet success story.

Around town, people recognize me, thank me for this piece or that. Some hug me. Others offer solutions to my myriad problems. Once in a while, a reader tries to get too close. It takes me a good stretch before I understand this, learn to draw boundaries. For about five minutes, I date my colleague, Coach, independently wealthy. I learn about the finer things in life, embarrass him at the country club, beg him to bring the Saab. I understand, if only momentarily, what it means to date for fun.

Louis and I, meanwhile, over the years, continue to tell each other to fuck off. Nick, Mr. low blood pressure, calmly intervenes as my mother has intervened between my father and me all these years. At one point, I report on autism, and in this reporting I find myself more challenged, and eventually, more successful than ever before with reporting. Then again, I also offer up a fictional piece on blow jobs, which everyone mistakes for an autobiographical essay.

It runs the week my son starts fourth grade. The first day of school, in the cafeteria, the dads approach me, clutching complimentary donuts, smiling, saying (wink implied), "Hey, I like your writing in the Chronicle." Sometimes it works out to a penny a word, or maybe $1 an hour. Sometimes it's much more. Always though, there's a payoff. Always it's worth it.

Louisa C. Brinsmade

By the end of 1993, we thought Slusher had looked into the darkness once too often when he announced his decision to run for mayor of Austin against his longtime political target, incumbent Mayor Bruce Todd. It shocked everyone except Daryl. He had come to the end of a personal era after the victory of SOS at the polls, and was eager for another conquest.

When Daryl moved on, I moved up. The excitement over being promoted to Politics editor lasted a full two minutes: the time it took me to walk back down the hall to my office from Louis and Nick's. I looked at Daryl's empty desk and had one encouraging thought: At least I don't have to share the phone anymore.

Spring 1994, the Chronicle came of age in politics; we had to figure out how to cover this race. At first, we fumbled and were as anxious and overeager as the candidate himself. We oversimplified campaign issues, ran four-page diatribes against Bruce Todd, overlooked Daryl's sparse political experience and ability to lead. Came up empty on objective coverage. There were long moments of silence in Politics meetings. What were we doing? How much of us as a political newspaper belonged to Daryl's work here? Were we helping, or hurting the cause? And what was the cause: Daryl Slusher as mayor, or Daryl Slusher as the Chronicle?

Daryl lost that election, but in 1996 ran for Place 1 on the council when Max Nofziger declined to run again. This time, we knew better. Like any newspaper, your success in covering the issues and the candidates is most often measured in complaints. In this, we were successful: Daryl called Louis, Nick, and me to complain about our coverage of his campaign. Once he won, our celebration was less exuberant in-house. We were proud, but we were separate. As it should be.

Later, during a friendly call from Daryl, he explained it was different being one of them. "It's much more of a gray area than it seems from the outside," he told me. "It's much easier to criticize politicians than to be one." I mourned the loss of our companionship, but it was the newspaper's gain, this growing-up thing, and I began feeling much smarter for the experience as we ran more stories on urban planning, neighborhoods, city services, and expanded our coverage outside the city's growing boundaries. The Politics section, like the man who defined its power, had entered a new urban phase.

Audrey Duff

In search of an "unbiased" reporter, Louis first asked me, then a freelance writer newly arrived from New York City, to cover a story for the Chronicle eight years ago. That's what you're reduced to when your former Politics editor makes a run at the mayor's seat.

It impressed me that Louis and Nick were struggling with how to cover their friend Daryl Slusher. They were fearful that no matter how hard they tried, they would be accused of a built-in bias toward their chum and against then-incumbent Mayor Bruce Todd, whom they skewered on a regular basis. What was especially honest about their approach was that they found me through a Texas Monthly editor; I had never spoken with or met either of them, nor had I expressed an interest in working for the Chronicle. They hadn't a clue about how I would portray their friend or the race.

Louis lured me with the assurance that I was to call it as I saw it and let the chips fall where they may. As an investigative reporter, I would have wanted to cover this David & Goliath story for any paper, how interesting to do it for The Austin Chronicle itself. What must have been the ultimate irony for Nick and Louis was that they ended up garnering criticism for being "too fair," a familiar refrain I was to hear in the years following when I became the Chronicle's Politics editor. Music to my ears.

Suzy Banks

Then along comes the 1994 Chronicle Christmas party. After several libations, I followed writers Marion Winik and Spike Gillespie to the Texas Monthly party around the corner at Evan Smith's house. They'd been invited, I hadn't. Instead of kicking me out, Evan's wife Julia solicited my advice on repairing her kitchen floor.

Seems she was a fan of my column in the Chronicle, and before I left the party a few hours later, I had a lunch date scheduled with Evan, who wanted to promote me as the White Trash Martha Stewart. I wrote an article for Texas Monthly the next spring and have been writing for them ever since.

I continued writing my column "Hearth and Soul" for the Chronicle, but after four years at the weekly task, the tone had shifted from playfully teasing to downright caustic. I was tired of questions about how to make hardwood floors look refinished without having to refinish them. I was doing less and less building myself. I wrote my last column in 1998, I think.

Occasionally, I meet people who recognize my name: "Oh, aren't you ... ?" I puff up, waiting for praise on my latest Texas Monthly article. And yet, even three years after the last "Hearth and Soul," here's what they invariably say: "I loved your column in the Chronicle. When did you stop writing?"

Virginia B. Wood

For years, my only concept of Phil Born was as a restaurant cook. I had no idea he was also a writer. In the early Eighties, I'd time my twice-weekly dessert deliveries so I arrived at the Basil's back door just before dinner service started. I'd drop off boxes full of Chocolate Orgasm cakes, and Phil would graciously send me home with a steaming plate of spaghetti and meatballs.

Ten years later, when I became a Chronicle contributor, I realized Phil had been submitting items under the heading "Food-o-File" for years. He wrote about wines, books, or some little hole-in-the-wall joint he'd just discovered, and his pieces always reflected his passionate interest in the subject at hand. By 1995, "Food-o-File" was where we filed restaurant news and reviews, and wrote about all things noshworthy.

Phil Born killed himself on his 39th birthday that May. His good friend Robb Walsh wrote a touching obituary for "Page Two" (Vol. 14, No. 36), and it was in that column I learned Phil had originated "Food-o-File." When I was offered a regular column later that year, it seemed only fitting that it be named in honor of the Chronicle's original food-o-phile, Phil Born.

Alex de Marban

The best stories are found in the trash. That's not really true, but that favorite phrase of mine aptly describes the brand of investigative journalism we practiced at the Chronicle, and the fervor with which we pursued it.

You see, our beloved city was under siege and changing fast. Dastardly developers were plotting to pave parkland. Their bureaucratic henchmen favored profits over people. The City Council, swayed by smooth-talking lobbyists, threatened to carve up the city's unique character. We had to stop them. If saving the city meant rummaging through chicken bones and lip-kissed napkins, so be it. Someone had to do the dirty work. And it might as well be me.

So, I accepted the "Council Watch" column the first month of 1995 and set to work soiling reputations. My goal was simple: bring down the City Council. It seemed like the perfect career move for someone still in J-school, but it was no easy task. Council meetings were long, issues were complex, and politicians were nasty. My favorite was the ever-brash Eric Mitchell, king of the one-finger salute. Council Member Mitchell taught me there was no need to rifle through wastebins. From him, I learned the best stories are sitting in the open, waiting to be told.

Once, after I reported that he voted to award his insurance company a city contract, Mitchell made an obscene gesture with his body and shouted, "You tell your editors I said, 'Up yours!'" Nick and Louis almost died laughing. They didn't laugh so hard, however, when Mayor Bruce Todd's wife threatened to sue the paper. I'd written that the Todds' new consulting business would profit from his political connections. It seemed obvious enough to me, but it didn't sit well with Lady Todd. Her lawyer responded with a letter full of pricey words that promised a lawsuit unless we retracted.

Nick smirked. Louis rolled his eyes. They did convene a meeting so our lawyer could explain our rights, but there was no retraction. That attitude is perhaps the Chronicle's most valuable trait. Nick and Louis created an environment where the truth flourished and journalists could make a difference. So we did. Former Chronicle Politics Editor Daryl Slusher was elected to the City Council in 1996, and the following year, Mitchell was replaced and the rest of the pro-development slate lost every race it entered. Better still, I didn't have to dig through the trash to make it happen.

Taylor Holland

Manager: Should we hire this guy?

Publisher: Is he qualified?

Manager: Here's his résumé.

Publisher: Yeah, but does he play volleyball?

Though this conversation probably never took place, it underscores the importance of volleyball at the Chronicle. Predating my employment in 1994, the game has evolved into an integral part of the newspaper.

Over the years, people have come and gone and we've worn 180 square feet of grass between the Chronicle offices and SXSW World Headquarters to dust, but our unwavering love of the game remains. Day in, day out, volleyball chit-chat litters the office: Volleyball? What time? Who's playing? Where's the ball? What happened yesterday after I left?

In the near-distant era when the production staff worked up to 16 consecutive hours in the name of the godforsaken Wednesday deadline, volleyball was our only respite, our only salvation. There we sat, in front of our computers, bleary-eyed, burned out, ready to stick a fist through a monitor or another staff member.

And yet, miraculously, an hour on the court could bring us back to life, ready to finish the issue with clear heads, better ideas, and an uncanny ability to correct the mistakes we'd already made. Like Cen-Tex versions of Japanese businessmen doing calisthenics, in due time it became our ritual and our religion.

Chronicle volleyball is misconstrued by certain nonparticipant staffers as a lazy, convenient route from the tasks at hand, which is true to some extent. But in these modern times of bulging staff and daylight hours, people regularly stay well after their work day to get in a few games. In some cases, it's their only exercise for the week. For them, and us, it's about the game and nothing else.

Once we step onto the court, separated by that beautiful sea of gravel craters that is the parking lot, work is forgotten. A few desperate nights, we've even lined our cars up in front of the court, headlights on, so we could play in the dark. "No! ... No!" screamed Louis in disbelief that his staff could be so pathetic.

New hires come in, get acquainted, and before you know it, they're addicted, too. Used to be, we had a hard time finding enough people to field a game of four-on-four. These days, eight-on-eight and beyond is the norm. Regular players include staff, children, part-timers, interns, and contributors.

At some point last spring, riding the high of our accelerating abilities, we formed a league. The Trees, the Killer Budz, the Crabs, Six Pak, and the Skunks (from SXSW). Most recently, classified and retail have mixed it up in that hot, dusty litter box that narrowly separates us from insanity. Bringing us closer together despite the heat, that court galvanizes us, and sometimes I wonder if the court was retired, how far behind it some of us might be.

Margaret Moser

Hopping is a little-admitted activity about the Chronicle. In the early days, I'd talk Mike Hall, Louis, Jody Denberg, and Nick into hopping like bunnies. We'd put our hands out like rabbit paws and jump up and down. Naturally, this only happened if we were happy or stoned, but sometimes you could drive by our 12th Street office and see Louis, Jody, or Mike on the lawn hopping like bunnies with me. It was a grand sight. But not Corky. He wouldn't hop.

Hopping like bunnies did not die out with the Eighties. Even now, when something we've worked hard on happens or we're victorious in some minuscule way, I'll flop my hands like paws at Louis and we'll jump up and down. We even did it in public, sort of. When John Cale played the Austin Music Awards in March 2000, Louis and I stood by the side of the stage holding our collective breath. Getting Cale to pay tribute to Velvet Underground bandmate (and ex-Austinite) Sterling Morrison by performing with Alejandro Escovedo had been a wild hare idea of mine, and after months of negotiating it was about to happen.

Louis and I were wide-eyed, literally gripping the stage. Cale came onstage and began playing "Waiting for the Man," the quintessential VU theme. Slowly we turned to one another with the biggest grins we could muster sliding across our faces. I nudged Louis, turning my back to Cale as Louis did the same. Ever so deliberately, I raised my hands into bunny paws, and right there, to that paean of drug addiction being performed by one of our favorite musicians, hopped. Louis did too.

Kate X Messer

No matter how you slice it, my tenure at The Austin Chronicle boils down to the Velvet Underground. Never mind that Marge and Margaret made sure that my Florida address of the Velvet Underground Appreciation Society, for which I worked, stayed on the Chronicle mailing list for years. It's not even that sometimes I just "Can't Stand It" or have spent way too many a "Sunday Morning" here, locked in the office.

It's something much more personal.

Part of it might be that the four folks whom I consider the main principals of this joint make me hear lyrics from that first banana LP. To wit:

Nick (usually at 3pm on any given Wednesday): "Waiting for the Man," of course.

Margaret: Why, "She's just a little tease ..."

Louis: "Kiss the boot of shiny, shiny leather."

And the life-saving Marjorie Baumgarten: "I'll be the wind, the rain, and the sunset. The light on your door to show that you're home ..."

My career? My job? Oh, it's more than that. "It's my wife and it's my life ..."

Greg Beets

When people ask what I do at the Chronicle, I liken my role to that of Newman on Seinfeld: I walk on in select episodes, say a few choice lines, exit stage right, and pick up a check. Then I return to my real role as Public Information Guy for the government, which is my equivalent of 3rd Rock from the Sun.

When I started showing up at the Chronicle offices around 1992, I felt like an intruder. But years of picking up CDs, dropping off floppy disks, taking meetings with my editors, and faithfully attending staff parties have made the place feel like my office away from the office. This is a good thing.

If you're a typical eight-to-fiver, you walk into the office every morning, say your hi-how-are-yous, pour yourself a cup of ambition, and get to work. Indeed, this is probably how it works for many full-timers at the Chronicle. But for me, the actual work of writing is best accomplished at home alone with no network e-mail messages or mundane office tasks to get in the way.

Conversely, a visit to the Chronicle is prime time to catch up with all the friends I've made over the years. In a given visit, I might muff a few returns as a volleyball stand-in, swap tidbits of Monkees trivia with Ken Lieck, and reminisce with Kim Mellen about our glory days in the gay bowling league. The sporadic nature of these visits lends them a novel, almost celebratory charm often absent in the land of daily grinds.

A recurring role in Chronicle Land is rewarding. I'm close enough to feel a part of the paper, but distanced enough to avoid taking that for granted. I'm close enough to get invited to the Christmas party, but distanced enough not to have to explain my actions Monday morning. And that, my friends, is just the sort of harmonic yin-yang I'm looking for in a job.

Stephen MacMillan Moser

Nepotism: a time-honored Chronicle tradition. In many ways, the Chronicle would not be considered a family-oriented publication. In other ways, it would. From the top of the masthead on down, Chronicle associates are often culled from spouses and close relatives of the staff. Staff writer Margaret Moser leads the pack; her mother Phyllis Stegall, brother Stephen Moser, ex-husband Rollo Banks, and ex-husband Ken Hoge have all contributed.

Margaret is followed by a close tie between Publisher Nick Barbaro, whose wife Susan Moffat and ex-wife Kathleen Maher have both written for the Chronicle, and Arts Editor Robert Faires, whose wife Barbara Chisholm is a regular contributor. The couple's daughter Rosalind has also contributed. The darkhorse is Louis Black; not only does his wife Anne Lewis write for the paper, so has their son Eli, who entered the short story contest recently, and should have a regular byline appear any day now.

That puts Louis neck-and-neck with Nick and Robert for a solid three-way tie, unless you count Nick's son Zeke's stint in the production department, and then it'd be Margaret in first, Nick second, and Louis and Robert duking it out for third. So remember: Maximize your chances of working at the Chronicle by marrying someone on the staff, having children with them, or having one of your parents marry one of the staff's parents so you can be their brother or sister.

Lisa Tozzi

The Chronicle is about temperatures and temperaments. Withering heat outside contrasted with a cold so biting inside that Amy Smith and I had to turn on a space heater and wrap blankets around ourselves in August. In the Politics office especially, the air conditioner just couldn't be regulated. Despite the climate, though, people were always piling in there. Now, I harbor no delusions: It wasn't for the company. It was because we had a door that closed when someone needed to vent. There was also the couch.

Long before I came along, that tweedy, faded, smelly old piece of furniture was given its name: the Crying Couch. Hundreds of dollars in change lodged under its cushions. A two years' supply of pizza, potato chips, and coffee was finely ground into it. Tissue lint, snot, and salty tears seasoned its fabric. I'm not even sure who named it, but during the year or so I dwelled in there, I made sure it lived up to its name.

See, I have weak tear ducts, and sometimes, lame as it is, lack of a snappy lead can make me well up. In my defense, a few times it was something far more serious that made me retreat to the Crying Couch. Sometimes it wasn't even my problems that got me going; I cry empathy tears something awful, so if someone else was having a go on the Crying Couch, I'd eventually join in. Yessiree, I may not have written too many cover stories, but I'll tell you this: On my watch, no one cried alone in the Politics office.

Now, crying may not seem like a fond memory to you, but in a bizarre way it's that for me. The Chronicle is as raw and real a place as I've ever known. It's intense and intoxicating, sometimes painfully honest and mean, like a big family's Thanksgiving dinner. It's boisterous and jokey, loving but with an undercurrent of waiting for mom to get drunk, dad to start yelling, and someone to push their plate away and storm off to their room. It's dysfunctional yet adorable. The Sopranos meets The Mary Tyler Moore Show.

I hear the crying couch is gone now, which is probably a good thing. Someone was bound to catch the plague from it sooner or later.

Sarah Hepola

A fight at the Chronicle was always a drama. Some people slammed doors. Some people threw things. Some people yelled. (Okay, most people yelled.) And some people cried.

I cried.

At times, when I broke down, the lifers would shake their heads and smile. "You have no idea know how crazy it used to be here," they'd say. "It's so much better now." They told stories of spectacular fallouts: people punching holes in the wall, kicking metal desks in, throwing tacos at each other. I cried anyway.

I cried in my cramped office and in other people's cramped offices. I cried in the Chronicle's one-lady's restroom, with women lined up outside bouncing impatiently. I cried because I wasn't good enough, and because I was so much better than this. I cried because editors and art directors and writers could never read my mind. I cried because crying is the first, best, and last refuge of the tired and desperate. And I was tired and desperate a lot.

Now, some people might say this is weak. A tad unstable. Those people are wrong. Some of my favorite people at the Chronicle are criers. Most of the time we were full-throttle, but when things fell apart (and they always did, do), we met in cramped offices, behind closed doors, with wet Kleenex on our laps. It's messy, but sister, we've all been there.

Kate X Messer

In the mid-Nineties, the national media was on its nauseating honeymoon with what had been gleefully tagged "Generation X," the hip, new youth culture supposedly driving the new economy. The media wanted a piece of that blushing, pierced, and tattooed bride bad.

Newspapers and national magazines were pissing themselves over their "discovery" of alternative newsweeklies, the hip, urban papers that "demographics" like the exploitable Gen X relied upon for their news. It was pretty funny to see dorky dailies like the Austin American-Statesman bend over backward to validate the culture that for ages they'd offhandedly dismissed as nasty little black-clad Goths.

Here at the Chronicle, we'd heard about XLent., the Statesman's attempt to "get rad." (Sort of like Poochie the Dog on The Simpsons, remember?) Some of us were concerned, outraged ... Some ambivalent, amused. Louis was unusually optimistic (at least publicly) that it would be good competition to keep us on our toes. Ad reps felt the heat, as suddenly, there was a well-funded, well-staffed competitor taking our advertisers very seriously. Even the kid of one of our distribution dudes got in on the act. Rush McNair made his spoof of the yet-to-be-released insert's logo into one that read "XL Not," employing the vernacular of the day.

As the launch of XL came closer, tensions grew. Would they affect our place in the community? How would we respond? Finally the first issue came out. They spelled Noam Chomsky with a "p." Tensions disappeared.

S. Emerson Moffat

When the Triangle fight started picking up speed in 1997, it put all of us -- Nick, me, the Politics department -- in a murky place ethically. As an officer of my neighborhood association, I was front and center on a contentious project, a logical person to call for an interview. But my marriage to Nick raised questions. After all, how do you cover the boss's wife?

Answer: You don't. Because the Triangle battle had multiple leaders, it was often easiest to just leave me out. Chronicle writers could almost always find someone else for a quote. I got plenty of ink in the Statesman, and the Channel 8 guys were filming in my dining room, but I was MIA in the paper that put food on our table. That was fine by me.

Every once in a while a writer would call -- "Hi, I'm [ ____ ] with the Austin Chronicle" -- and I'd know they were a freelancer or a new hire. Usually, I told them up front about my relationship with the paper. Sometimes, I just played dumb and gave them the interview. I knew one of the editors would catch it anyway.

If I absolutely had to be mentioned, my name was always followed by the obligatory brackets [married to Chronicle Publisher Nick Barbaro]. As a writer, I knew how irritating that device was, so most of the time, absence simply worked better. Humorously enough, I found myself bracketing my conversation at home: "I'm telling you this as my husband, NOT for publication." Since Nick is famous for his bad memory, this usually worked -- except when he'd forget that I told him not to tell.

Meanwhile, I was contending with ethical gaffes in my own camp. "Why can't the Chronicle give us more coverage?" "Can't you ask for a cover story on this?" "It would really be great if we could get a big write-up right before we go to council!" I would have to explain yet again that, no, it didn't work like that.

The Triangle is behind us now, and I've moved on to other battles. The ethical dance continues.

Things I never do: ask for a story, ask Nick to ask for a story, exchange conjugal favors for a story, ask to see a story in advance, sit in a Politics department meeting, have anything to do with candidate endorsements.

Things I do: hang around the office, leave our son there if I have a meeting and no child care, gossip with the staff, including the Politics writers, tell my husband what I really think.

My mother was a journalist and honest to an almost pathological degree. She raised me on the sanctity of a free press, and I realize more and more, as I walk this fine line, that I owe my balance to her. Mom always said never do anything you wouldn't want to read about on the front page. I figure as long as I stick with that, we'll all be okay.

Jen Scoville & Taylor Holland

It was a hot, ugly night in September 1997, when Chronicle staff gathered for a going away party for then-Politics Editor Louisa Brinsmade at Barbarosa. (The Barbaros were on vacation, and Jen swore they wouldn't mind.) Ken Lieck was in rare form from the outset, exhibiting a terrifying contortion he called the "happy clown," a crab walk mired in sexual innuendo that left emotional scars on most of the female guests. Audrey Duff, heir apparent to the Politics chair, took his keys and hid them, not knowing Ken had an extra set in his pocket. Lieck bellowed an obscenity from the living room and left in a cloud of horseplay gone bad. We felt the need to be cleansed. "Let's go swimming," someone suggested.

Carrying the torch of Chronicle debauchery in fine style (see cover), we crashed many apartment pools that summer, but this would be our first foray into criminal trespass. It's hard to remember exactly who was there and precisely what happened, but our recollection is that Politics writer Kayte VanScoy, the only sober one of the bunch, instigated a movement to start a second party in Shipe Pool. We were just drunk enough to believe her.

The first four over the high fence were a tangle of arms, legs, and asses. It wasn't pretty. Someone waiting their turn figured out that by getting on top of the cement poolhouse and climbing down, one could circumvent the fence altogether. The rest of us were already in the pool by then, splashing and making out (kissing was big that summer, see photos). After 10 minutes, an hour, however long it was, a spotlight skimmed across the surface of the water. "Get out of the pool," blared the loudspeaker. We froze, our heads finding the water around near the edge, naively thinking the cops couldn't see us. Some dove to the bottom and tried to hold their breaths until the cops went away, only to emerge gasping, obvious. "Um, we can see you," blared the loudspeaker. "Get out of the pool."

Everyone crawled out in their wet underwear (and we thought we knew each other well) and climbed the fence. We were eventually issued misdemeanor trespass citations, some of us donning aliases. On the walk home, we were somber but relieved. And sober, because that's what almost getting arrested while housesitting for your boss will do. If we were lucky, after a thorough house cleaning, they'd never know. On Monday, however, we learned that Nick's wife Susan had led the effort to collect private funds to keep Shipe pool open after Labor Day. In other words, if not for the Barbaros, we wouldn't have gotten busted in the first place!

Robert Faires

All right, it was a duck standing on a log with a dildo strapped to its back. You couldn't tell it was a dildo on our cover, because that part of the image was pixilated and covered with the word "censored," but if you looked at the accompanying story inside, yes, it was a dildo.

Now, I'm not saying a duck with a dildo on its back is a cultural artifact on par with a Rembrandt. I will say, however, that while it may not have been great art, it was a damn fine cover. Not because it was sensationalistic, although you want a cover to grab people, and sometimes sensationalism is justified in the pursuit of that. I'd argue that this was one of those times.

No, it was a damn fine cover because the image captured all the key elements of the story within: the deliberately provocative quality of this work of art, which led to its being pulled from an exhibition at the Austin Museum of Art, and the larger issues of what constitutes art, what constitutes offensive art, and what constitutes censorship -- all issues being widely debated at the time (1997), in the wake of attacks on the National Endowment for the Arts. That picture summed up 1,000 words.

It was also a sign of the times. In the Nineties, the arts became news in Austin in a way they hadn't previously. As the city evolved, its ballet, symphony, opera, art museum, et al., matured. They grew bolder, more willing to take risks, while expanding their visions and the way they worked. At the same time, the smaller, independent artists and companies jumped to a new level, generating the same original, iconoclastic art they had been, but tighter, more organized, and it drew attention on the national stage.

The Chronicle reflected that growth, taking note of the issues, news, and personalities in the Austin arts community and featuring them on its covers more frequently than it ever had. Nick and Louis are the guys to credit on that score: When a stone-broke former freelancer showed up on the paper's doorstep in 1993 looking for a handout after two years of gallivanting in sunny Southern California, they had the savvy to offer him a full-time position as Arts editor. Having a staffer focus exclusively on the arts scene made all the difference.

It may have been just a duck with a dildo, but it's also an emblem of pride for the guy who gets to tell arts stories every week in these pages.

Ben Plimpton

Why a Duck? The only time a dildo has appeared in the Chronicle (that is, if you don't count Harry Knowles). It was the only cover I did that appeared in the Austin-American Statesman as well. It took me a really long time to figure out how to mimic the COPS-style, pixilated-face effect at 300 DPI. The challenge was to make sure that most people could recognize the dildo, without being able to clearly see the actual "nuts and bolts" of the thing.

Kate X Messer

In 1998, we gave the Chronicle's annual Musicians Register a quinceañera motif, as it was our 15th compiled listing of local musical artists. Wacky photo genius Toddy Wolfson and I conjured the concept along with local rock poeta Tammy Gomez, who was draped in her own, original quinceañera dress on the cover and dripping with an attitude. It perfectly summarized our local music scene: feisty, restless, and underdoggety. In 1999, the teen theme continued with our cover tribute to the Rolling Stones Let It Bleed LP, with Todd and me at the helm again (my fave Chronicle cover ever).

Fitting, in retrospect, the puberty theme -- as that period marked a maturity from the Chronicle's pen-and-paper data compiling system to more mercurial methods employing keyboards, databases, and the Web. Progress was no convenience; it was necessity. I had seen the haggard snipes between editors and proofers stuck in a Musicians Register lockdown from processing previous issues. For proofers, it wasn't a choice to earn the extra weekend's worth of wee cash for two 12-hour days of manual data sorting. Like volunteers for those military missions of no return, it was a mandate. That, coupled with antiquated methods of record keeping (notepads, accordion files), had us in fits.

That changed a bit when we streamlined into the modern world. The upshot? Speed, accuracy, more time to hone and buff. Now, it is easier than ever to utilize Senior Account Executive Carolyn Phillips' brainchild on the Web. The downside? During this period, Publisher Nick Barbaro went on a bender, documenting every subgenre of our town into a freakin' guide. Who knew Pandora's progress held such dark disease within her box?

Taylor Holland

The Chronicle's Halloween mask covers have always been a hit with readers, and every year we wrestle with far-out ideas before finally settling on something most can live with. Of the approximately 215 covers I've done for the Chronicle, then-Governor George W. Bush as an Oompah Loompah (1998) qualifies as one of our strangest and least understood.

Originally, the idea came from Kim Mellen, who piped up in an editorial meeting that W. looked like one of Willie Wonka's crooning midget workers, which related to an upcoming piece on oompah bands for the Music section. Immediately, I fell in love of the idea, not only for the fact that I love Willie Wonka the film, but I knew W. would one day be president and the thought of jumping on him early and as often as possible appealed to me greatly, and still does.

The tough task of rendering George-as-midget fell to then-UT art student Michael Sieben, who toughed it out through four revisions and at least two sleepless nights to deliver the goods. Sieben never called for work again, and stands as the only artist I ever tortured out of illustration work in a single week.

Practically everyone hated this idea except Kim and myself, and some still don't get it, but it's their loss. To this day, the mask hangs on the wall in my office, because it's hilarious and frighteningly realistic. In the years since, we've done four or five Bush covers, the best being Bush as Alfred E. Newman by Tom Tomorrow and the "Black Tuesday" cover: a black "W" on a black background the week of the general election last November. I love them all as much as I despise George.

Raoul Hernandez

1999 had already driven a stake through our liberal hearts when Kirk Watson, Daryl Slusher, and the rest of Austin's Tammany Hall crew sold Liberty Lunch into rubble for 30 (million?) pieces of gold: dot-com dividends. The Electric Lounge was already in the ground, so when the Toadies beat a hole into the Lunch stage on that last night of July, the Live Music Capital of the World went into shock, dazed. Betrayed by local politicians with Smart Growth slogans on their lips and small ideas in their wallets. Only a calamity could be worse.

That came on Thursday, Nov. 18. Marge Baumgarten and I were coming from the Alamo Drafthouse, crossing the street. Someone yelled my name, and as I reached the parked cars in front of Antone's, Louis Black pulled up beside me, rolled down the window, and motioned to a driveway up the block. We stood in the street, traffic moving past us. "Have you heard?" he asked. Those are bad words to hear from your editor standing in the street. Louis put a hand on my arm, a pained, empathetic look on his face. "I'm sorry. They found Doug Sahm dead. You've got the cover next week."

Who knows what he said after that, or even if he did say anything? Those words were enough. We got into Louis' car and drove up to KUT to meet Margaret, who was sitting in with Larry Monroe and Texas Tornados drummer Ernie Durawa for some on-air consolation. Everyone was upset. Jody Denberg showed up, and most of us headed to the Hole in the Wall. Others came. I did a tequila shot in Sir Doug's honor, and everyone followed suit. Before long, we were back at the Home of the Blues, looking for Clifford Antone. When we found him, we all bowed our heads together. Only one thought was running through my mind by this point: Hit ... the Ground ... Running.

You see, Louis' "sorry" hadn't been because Doug had died. He was devastated about that. No, his condolence had been for me. Doug Sahm had died on my watch. As a five-year vet of the Music editor hotseat at the Chronicle, Sahm's hometown paper, suddenly all eyes were on me. On us. I could feel the whole of Austin collectively hold its breath waiting to see how the Chronicle would celebrate a local musician second perhaps only to Willie Nelson in symbolizing the city and its music scene.

Over the next six days, Margaret and I beat the bushes for writers, and paid house calls to illustrators, poster artists, and photographers in gathering honorariums. Christopher Gray even faxed the president for a few words. When Burton Wilson appeared in our lobby with the shot that became our cover, one immutable truth made itself clear to me: The Chronicle is a paper of the community, and in situations such as these, communities come together. Austin did. For Doug, the State Musician of Texas.

Marjorie Baumgarten

The Chronicle's commitment to film extended back to our days with CinemaTexas, where many of us had originally met. The weekly publishing schedule instituted in 1988 proved a particular boon to the paper's film section, as it allowed us to provide coverage and reviews that were more timely than we could manage under the old biweekly deadlines. The weekly schedule also allowed us to provide show times and become the full-service listing we aimed to be. Eventually, in addition to reviews, the Chronicle started a Screens section with feature stories, "Short Cuts," "TV Eye," and video reviews appearing on a weekly basis.

As if in recognition of all the hard work they'd witnessed, the gods closed out the decade by bestowing upon me a very special treat. In November 1999, I had the privilege of printing in the pages of the Chronicle a new piece of writing by the mother of all film critics, Pauline Kael (Vol. 19, No. 12). In frail health, Kael had retired from The New Yorker in 1991 and had not written anything new since. That is, not until Charlie Sotelo of The Show With No Name and SXSW Film sweet-talked her into contributing something to the Sam Peckinpah monograph he was putting together for the Austin Film Society. She delivered 2,000 words of smart commentary and gave the Chronicle permission to reprint it. I had now published the capo de tutti of critical capos, Pauline Kael: What aspirations could possibly remain?

During one of our phone conversations, Kael extended an invitation to visit her if ever I was in the Great Barrington, Mass., area. Upon hearing this, Louis Black did a very un-boss-like thing and practically shoved me out the door, saying I was nuts if I didn't get on the next plane. He had a point; it wasn't long before Charlie and I were Berkshires-bound. The whole trip is a saga best told Shaherazade-style, but suffice it to say Kael was welcoming, gracious, curious, and nurturing -- a wonderful host and cook. The visit surpassed my wildest dreams. One story in particular comes to mind in light of Kael's death yesterday (Sunday, Sept. 2).

Wanting to see a particular movie at her neighborhood cineplex, Kael invited her visitors, who happened to have a rented car, to accompany her. Watch a movie with Pauline Kael? What fool would say no? Turns out this fool had already seen the movie and didn't especially relish the idea of seeing it again. The solution? Charlie went with Kael to the movie, I stayed back at her house to finish writing a Chronicle story that was due. I took my laptop upstairs to Kael's pink marble writing table, stared off into the wooded landscape, pinched myself silly, and wrote like a woman possessed.

In the early days of the Chronicle, the joke goes, we produced the whole thing with ballpoint pens and scrap paper. Here I was at the dawning of a new millennium, writing with my laptop at Pauline Kael's desk. I'm broken-hearted that there won't be any future occasions to deepen my friendship with Pauline and that her voice is now quieted forever, but the opportunity to publish and meet this legend rank among the highlights of my life. None of this would've ever happened without the Chronicle.

Raoul Hernandez

This time, it was the "You're probably not gonna like this" chuckle, and Louis was standing at my desk, January 2000, giving it. "This is just an idea," he prefaced with a slipping grin. "We can definitely talk about it. Nothing's concrete." Uh oh. "South by Southwest daily supplements," he announced, eyes aglow. "I'm sick of the Chronicle doing all the work, all the advance coverage, and then the Statesman setting the tone of the festival with their snide coverage."

He explained how the Chronicle could rent a hotel room downtown, install some computers, and have the Music staff come in off the street, bang out 200-300 words, and then e-mail the office where, ahem, someone would be waiting to edit the copy. A skeleton production crew could do a quick design, by say, 2am. Music reviews, "Dancing About Architecture," maybe a few food write-ups. SXSW Film coverage. Do an 8-10 page editorial hole with 10-14 pages of ads; advertisers would get a package deal, one price for all three supplements -- say, Thursday, Friday, Saturday. Something like that. Not all the details had been worked out. Just an idea he and Nick had discussed.

It sounded like an April Fool's joke. Especially the punchline about the beleaguered Music editor, who the previous year had edited 44,000 words worth of "Picks & Sleepers" in one 18-hour sitting, leveraging heaven and earth by first advancing a music festival with more than 1,000 acts playing and then covering them nightly while streamlining the mothership into a jet. Louis grinned, rocking back and forth on the balls of his feet. It was a beautiful day outside. Gorgeous. Crisp, cool. Perfect day to sign a death wish. Which I did; it was a great idea! Inspired. The half-wits at the Statesman had become tiresome. We were the paper of record in Austin, time to put some history on the page.

So we did. I was scared shitless. Trouble-sleeping-type scared. I remember racing like a demon from the Austin Music Awards back to the Chronicle that first night, and spewing out a review in a blind panic as the proofreading and production crew showered me with questions. Somehow, they got answered, and we got done. I remember Louis hugging me the next morning on the floor of the Convention Center after he'd seen Dave Derrick doing his best Doug Sahm on the cover of the very first Chronicle Daily. A hug like I'd given him another son. Nick was positively giddy about it at the trade show later.

Night two was a little less nerve-racking -- except that was the night the Sheraton had a fire scare and the entire hotel was evacuated, leaving Team Chronicle on the sidewalk outside and the clock ticking like a bomb. That, I think, may have been the same night Chris Gray chose to re-enact Animal House and incapacitated himself as South Austin news bureau chief. My night off, I was ejected from the Atomic Cafe. It went so well that this year we published four supplements instead three. Local history is our business.

Margaret Moser

Belton was the big white smelly dog who lived at the Chronicle by day and went home with Nick at night and on weekends. He was already entrenched as the Office Dog when I moved back from Hawaii 1991, but we fell in love, Belton and I, carrying on secret trysts right under everyone's nose. I'd put on red lipstick and kiss Belton on the head. No one was the wiser.

Nick was Top Dog, of course, and Belton responded thusly without fail. Sometimes Nick would sit holding this great galoot of a dog in his lap, and it was like perfect father love. But Belton regularly sought the shelter of my office with Marge and lay on the gross orange carpet, leaving a coating of smelly white dog hair. I had a special whistle, which Belton knew meant chips from Tamale House. Belton loved me, because I made him nachos. He was a real mooch. He'd have these howling attacks that went "woo-woo-woo-roo-roo." We called them his acid flashbacks. Rollo drew some of this into his Year of the Dog cover.

Belton inspired not only the much-celebrated Finding Day Pageant, but a host of songs. To a Dick Price tune, Susan would sing, "The toys of Mr. Belton, they don't last too long. The toys of Mr. Belton, first they're here and then they're gone. He eats them so completely, we have to buy him more each day. Though his chewing is atrocious, and he sometimes is ferocious, we really love him anyway! B-E-L-T-O-N! Mr. Belton all the way!" Belton's favorite song was "Happy Birthday," because not only did the whole staff sing, but it meant food and maybe cake!

When Belton grew old, he did so at an astonishing rate. He became too blind to keep around the office and finally stopped coming in. I heard bleak reports from the Barbaro household about his declining health and eventual inability to walk. He was suffering. One Thursday in the spring of 2000, Nick told me they were having Belton put to sleep.

I climbed in the back of the station wagon with Belton. Nick was driving, Susan was in the front seat crying, and Raoul sat in the middle. I held Belton's big, warm, odorous body and sang "Happy Birthday" and then the ever-popular "Belton Loves the Little Hamsters" ("all the hamsters in the world, red and yellow, green and purple, he likes them with maple syrple. Belton loves the little hamsters of the world!").

Nick carried him inside the vet's office and into a room where Susan, Raoul, and I were sniffling badly. After the injection, we gathered around Belton, loving him and reassuring him. A painful silence fell in the small room and a deep, painfully anguished sob emanated from next to me. I couldn't even look at Nick, who uttered the cry. He was my publisher, my rock, my longtime friend and compadre, and the one who never cracked. I took Raoul by the hand, and we left Susan and Nick in the room, saying goodbye to beloved Belton forever. ![]()