Two APD Officers Indicted for Murder in 2019 Shooting of Mauris DeSilva

Death led to calls for better mental health crisis response

By Austin Sanders, 6:30PM, Fri. Aug. 27, 2021

A Travis County grand jury has indicted two Austin police officers for first-degree murder in the fatal shooting of Mauris DeSilva, who was brandishing a knife while undergoing a mental health crisis on July 31, 2019 at the Spring Condominiums in Downtown Austin.

At the time of the shooting, Officers Christopher Taylor and Karl Krycia had both been with the Austin Police Department for five years. Nine months later, Taylor would fatally shoot Michael Ramos, an unarmed Black and Hispanic man, as he slowly fled in his vehicle after being shot with a lead-pellet bag. The officer has been on paid administrative leave since Ramos' death in April 2020, and in March 2021 was indicted for first-degree murder in that case. APD Interim Chief Joseph Chacon announced after today’s indictments were made public that Krycia would likewise be on leave until his case concludes, and that he would defer discipline in either case until after the criminal charges are resolved.

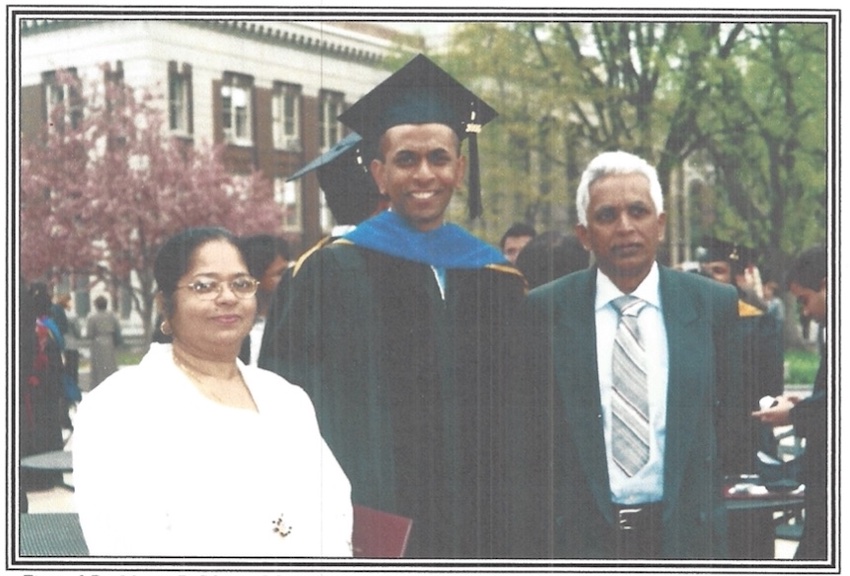

DeSilva’s father Athige Denzil DeSilva has filed a civil lawsuit against the two officers and the city of Austin. Filings by the plaintiff and defendants in that suit lay out the circumstances that led to Mauris DeSilva’s encounter with the APD officers. According to the complaint by Denzil DeSilva’s attorney Aspen Dunaway, at around 5:00 p.m. on July 31, one of DeSilva’s neighbors called 911 to report that the Ph.D. neuroscientist, originally from Sri Lanka, was undergoing “another mental episode.” That neighbor specifically requested that a mental health officer respond to the call; at the time, DeSilva was wielding a large knife.

DeSilva’s mental health challenges had led to such calls before. In February 2015, officers encountered DeSilva under similar circumstances, threatening himself with a knife. In that case, DeSilva was taken into custody and hospitalized without incident. In May 2019, APD identified DeSilva as needing an “emotionally disturbed person intervention,” because of his history of mental illness. Two months after that, on July 7, DeSilva was committed to a local hospital on emergency detention. Three weeks later, he was shot and killed by Taylor and Krycia.

Dunaway claims in the civil lawsuit that a mental health officer was available to respond on July 31, but did not, despite APD’s foreknowledge of DeSilva’s condition and the content of the 911 call. Taylor and Krycia’s attorneys argue in their response that the officers were “without sufficient knowledge” to determine if that allegation is true. Either way, no mental health officer responded; none of the four officers who did respond had any mental health crisis training. The civil suit argues that both of these facts contributed to DeSilva’s death.

The Circumstances of the Shooting

Upon arrival, according to the lawsuit, the officers talked with a Spring employee who said that DeSilva was acting “unstable” and that he was “known to be unstable.” This employee told two of DeSilva’s neighbors (as they recount in the filing) an attempt was made to lock DeSilva out of the building, but he was still able to reach his apartment. He then went to the building’s fifth floor, which includes a gym and other common areas.

As Dunaway frames it in his complaint, the responding officers knew that DeSilva “had a history of mental health contacts, was currently experiencing a mental health crisis, and had not threatened or harmed anyone other than himself.” In his response, Taylor and Krycia’s attorney Blair Leake acknowledged the officers were told by those on the scene at Spring that DeSilva had a history of mental illness and was in need of mental health assistance; they deny knowing whether or not he had threatened or harmed anyone else.

Once the officers learned DeSilva was “now moving freely through an occupied residential building while wielding a large knife and acting erratically,” as Leake writes in his filing, their mission changed: “Suddenly, what the officers believed was a ‘barricaded suspect’ situation had evolved into an exigent circumstance requiring swift action to prevent imminent danger to others.”

From here, Dunaway and Leake offer slightly conflicting accounts of what transpired. Both agree that after seeing DeSilva on the fifth floor via security camera, the four officers decided to take the elevator up. DeSilva was, at the time, in the hallway near the elevator; Dunaway claims that had the officers taken the stairs and entered the hallway at a safer distance, they may have had more time to confront DeSilva before resorting to lethal force.

In the elevator, the officers devised their strategy. One officer would not have any weapon drawn; one officer – Joseph Cast – would have his stun gun drawn so a less-lethal option would be available. Taylor and Krycia would have their firearms drawn in case lethal force was needed. Leake in his filing denies that the officers had drawn their weapons before the doors opened at the fifth floor.

DeSilva was facing away from the officers while holding the knife to his throat. Taylor and Krycia shouted for him to drop the knife. From Dunaway and Leake’s conflicting accounts, it can be surmised that DeSilva did lower the knife (thus complying with the officers’ commands, according to Dunaway), but did not drop it (thus not complying, according to Leake). He then turned and moved toward the officers, while still holding the knife.

Cast fired his stun gun, but before waiting to see its effects, or attempting other less-lethal uses of force, Taylor and Krycia began firing; DeSilva would later die from his wounds at Dell Seton Medical Center. Leake argues this was necessary to defend the officers; Dunaway writes that “despite having knowledge of Dr. DeSilva’s prior mental health contacts and of his ongoing mental health crisis, officers responded as if this were the scene of a violent crime.”

APD's Mental Health Crisis Response

That response lies at the heart of Dunaway’s allegations that Taylor and Krycia’s actions represent a “pattern of police brutality” at APD and insufficient training for its officers on how to deal with citizens undergoing mental health emergencies. A 2019 report by the Human Rights Clinic of the University of Texas School of Law and the Austin Community Law Center found that Austin has the highest per capita rate of police shootings during mental health calls among the nation’s 15 largest cities. “It is obvious that mental health training of additional officers is required to prevent unjust outcomes … for people going through a mental breakdown,” Dunaway writes in his filing.

Many justice advocates, members of the City Council, and the city’s Reimagining Public Safety Task Force all agree. DeSilva’s killing added urgency to efforts to both improve APD’s mental health crisis response and potentially shift some of these calls toward non-police interventions. In December 2019, Council adopted a wide-ranging resolution that, spurred by complaints from former cadets, began the ongoing reboot of the Austin police academy. Subsequent internal audit findings found that its “paramilitary” approach produced officers inclined to act as “warriors” engaging in battle with Austinites rather than “guardians” sworn to protect their rights.

The volunteers and APD staff working to revise the curriculum have told the Chronicle that how cadets are taught de-escalation strategies is the most important topic to address. Last week, that revision work was paused as even more problems were uncovered with the existing curriculum being used with the current cadet class, which is supposed to be a “pilot” of the new approach. We’ll have more reporting on this in the week ahead.

Kathy Mitchell of Just Liberty, who is one of those volunteers as well as a member of the RPS Task Force, addressed the need for such a culture change in her reaction to today’s indictments. “The days when police could just shrug off a case like this as ‘suicide by cop’ are long gone, and that is a good thing,” said Mitchell in a statement from the Austin Justice Coalition. “Our first responders should never, ever kill the people they are called on to help. APD knew that Dr. DeSilva had a history of mental illness, and the fact that he had a knife in his hand did not make this OK.”

In a statement responding to the indictments, Dunaway said, “The city of Austin has a long history of underfunding mental health officers in the police department. The City’s failure to establish an appropriate mental health crisis response directly contributed to Dr. DeSilva’s death.” Referencing Mauris DeSilva’s father Denzil, the statement also said, “Although the loss of his son will always be felt, these indictments of the officers who shot his son to death will begin to help him heal.”

More Outrage from Union, Lawyers

No Austin police officer has ever been convicted of murder for an on-duty shooting, and none have been indicted in at least a century; Taylor has now been indicted twice. “Our system depends on trust in the process,” said Dexter Gilford, director of the Civil Rights Unit at the Travis County District Attorney’s office. “We trust the grand jurors took seriously their commitment to consider the cases before them, and, in this instance, to return indictments. We know these decisions are not easy, and we appreciate the time and concern they put into this case.”

Criminal defense attorneys Ken Ervin and Doug O’Connell, who have ties to both the Austin Police Association and the pro-police political action committee Save Austin Now, are representing Taylor in both murder cases, along with a number of other Central Texas peace officers indicted in recent months. As such, they’ve been waging a bitter, noisy campaign to discredit District Attorney José Garza, including multiple allegations of misconduct relating to the grand jury, which so far have gone nowhere in court.

Today, the pair broke the news of Taylor’s indictment before it was confirmed by the D.A.’s office, with their usual spin: “What happened was undoubtedly tragic, particularly if it is true the man was experiencing a psychiatric episode, but in no way was this murder,” they said in a statement. At a later press conference, the two were joined by APA President Ken Casaday, who let loose on Garza for indicting “heroes” who were defending themselves: “This is ridiculous and is getting old. These officers did nothing wrong, and I can't wait for this to go to court.”

“Until now we have refrained from accusing [Garza] of waging a war on police officers,” Ervin and O’Connell said, “but after today’s indictments, we do not know how else to characterize what he is doing.” This may be a surprise to Garza, as Ervin and O’Connell have been attacking him from nearly the moment he took office in January. “We’ve seen what happens now,” Ervin told KXAN in an April interview where he raised the prospect of seeking to move his clients’ trials out of Travis County. “Mr. Garza comes in, and he got a grand jury to indict officers just like he said he would.”

Garza said then, and has since, that he has never expressed a public opinion on the guilt or innocence of the officers, but has offered compassion for the victim’s families.He has since taking office has made good on his campaign pledge to present each case of alleged excessive use of force committed by a peace officer to a grand jury, after many such cases (including the DeSilva shooting) did not move forward during the tenure of his predecessor Margaret Moore, whom Garza defeated in the July 2020 Democratic primary run-off election. A total of 12 cases have been presented so far; six have led to indictments, with Ervin and O’Connell representing most of the defendants. In July, Garza dropped one of those indictments after discovering exculpatory evidence in the case file that a prosecutor under Moore hadn't disclosed.

A Vendetta, or a Sea Change?

A standard complaint of the duo is that Garza has not allowed their clients or friendly witnesses to address the grand jury, which he has no obligation to do. In the case of Daniel Perry, facing murder charges after killing protestor Garrett Foster on Congress Avenue last July, their ace in the hole is a freelancing APD detective, who's been told to cool his jets by the chain of command. In retaliation, O'Connell both filed to have Perry's case thrown out (which District Judge Cliff Brown declined to do) amid claims of Garza's "corruption" and filed misconduct complaints against Chacon and APD Assistant Chief Richard Guajardo (the city Office of Police Oversight has recommended an independent investigation of the whole matter).

In this case, it’s a third-party use-of-force expert witness named Howard Willams, whom the attorneys say they met with in July to discuss a number of the cases they are defending. In that meeting, they understood Williams to have described the shooting of DeSilva as a justified use of force. After learning about Taylor’s imminent indictment, the attorneys called Williams on Thursday, Aug. 26, to confirm they understood their July conversation correctly.As the D.A. presented the case, O’Connell says he saw Williams sitting outside of the grand jury room, and “it's reasonable to conclude he was called there to testify,” O’Connell said at their press conference. “Somehow, a decision was made by someone, perhaps the District Attorney, not to allow him to testify.” The D.A.’s office declined to comment on O’Connell’s speculation, citing section 20A.204 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, which prevents prosecutors from disclosing grand jury proceedings. Those statutes also prevent Williams from disclosing if he had been asked to be on standby to testify, either at Garza’s or the grand jury’s request. This did not stop Ervin and O’Connell from (in their statement) “a continuation of DA Garza’s pattern of controlling what the grand jury sees and excluding certain evidence not calculated to produce an indictment.”

In an unusually direct response to the pair’s charges, a spokesperson for the D.A.’s office said in a statement later Friday, “The allegations that DA Garza, or anyone acting in his capacity, would not let Dr. Williams testify are false. The State presented a thorough and balanced grand jury presentation consistent with its obligations under article 2.01 of the Code of Criminal Procedure,” which lays out the general duties of a district attorney.

What the lawyers and Casaday see as a vendetta, advocates see as a welcome sea change. “Today we thank DA Jose Garza for diligently pursuing this criminal case against one officer who killed two different people in the span of less than a year and a second officer who also shot DeSilva,” said AJC senior policy director Sukyi McMahon. “This case has waited far too long for justice. Dr. DeSilva was killed more than two years ago, and the case languished until Garza finally started to bring police cases to the grand jury.”

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.

Austin Sanders, Feb. 16, 2023

Austin Sanders, Feb. 3, 2023

July 12, 2024

July 5, 2024

Austin Police Department, Mauris DeSilva, Christopher Taylor, Karl Krycia, Michael Ramos, mental health crisis response, Spring Condominiums, Travis County District Attorney, Jose Garza, Dexter Gilford, Aspen Dunaway, Denzil DeSilva, Blair Leake, Ken Casaday, Ken Ervin, Doug O'Connell, Howard Williams, Kathy Mitchell, Sukyi McMahon, Austin Justice Coalition