CCA Considers Hank Skinner's Death-Case DNA Appeal

Should never-before evidence be tested for DNA?

By Jordan Smith, 2:04PM, Wed. May 2, 2012

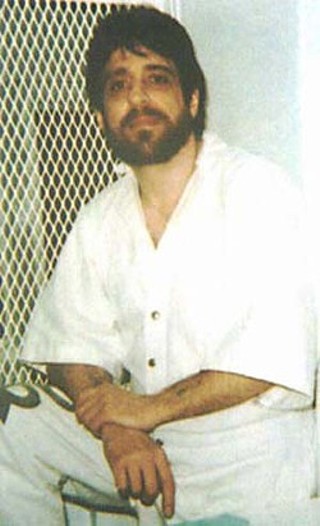

Whether death row inmate Hank Skinner will be given access to DNA testing that could demonstrate he is not guilty of the 1993 killing of his girlfriend and her two sons is now in the hands of the Court of Criminal Appeals, which considered the case during oral argument this morning.

Among the items of evidence that could be subject to testing for the first time, should the CCA allow Skinner the access he's been seeking for more than a decade, is a windbreaker – its cuffs spattered with blood, stained with sweat, and with two human hairs attached – that was found next to the body of Twila Busby, who had been bludgeoned to death in her home in 1993. She shared that home with her boyfriend, Skinner, and her two grown sons who were also slaughtered that night in the home. Also never before tested is a rape kit from Busby, a bag containing bloody knives and a bloody cloth, evidence found under Busby's fingernails and human hairs found clutched in her hands. To hear Skinner's lawyer Rob Owen tell it, if this evidence is finally tested, and comes back with DNA belonging to someone other than Skinner, it would be valuable evidence and, had it actually been available at the time of his trial nearly 17 years ago, would likely have convinced a jury that Skinner was not guilty of the grisly triple murder. "It changes the picture," he argued before the court. "Having the DNA evidence makes the jury look at the other pieces of evidence differently. Because I think jurors are inclined to accept DNA evidence as reliable."

Whether state law affords Skinner access to that evidence will be up to the nine judges of the CCA to decide.

To hear the state tell it, Skinner's bid to test the evidence now is merely an unreasonable, and unlawful, tactic undertaken to delay his execution, Solicitor General Jonathan Mitchell argued to the CCA this morning. Indeed, according to Mitchell, the circumstantial evidence pointing to Skinner's guilt is overwhelming – and there's no reason to believe, not only that DNA testing would cast any doubt on that evidence, but also that a jury would be willing to overlook the mass of circumstantial in favor of the finality of the scientific.

Mitchell argued that Skinner shouldn't be allowed to test the evidence now because his suit is a "frivolous" attempt to delay his death by lethal injection. He had the opportunity to test the evidence at trial in 1995 and yet his lawyer chose not to, as part of a deliberate strategy to avoid having before the jury any concrete evidence of Skinner's guilt. Skinner later argued on appeal that the decision to avoid the testing could be seen as evidence of ineffective assistance, an argument the court dismissed. Had the court agreed that Skinner's trial counsel was deficient then perhaps he would have a winning claim to access DNA testing now, Mitchell argued; in other words, it was Skinner's fault that the DNA was not previously tested, and he can't now get a do-over. To allow Skinner to access the DNA now, would be to incentivize inmates across the state to forgo testing at trial (instead accepting the risk of being sentenced to death) in order to forestall execution later by requesting DNA testing.

That argument did not seem to impress the judges, several of whom noted that state lawmakers removed the so-called "fault provision" of the state's post-conviction testing law in 2011 – a noncontroversial repeal (prompted by Skinner's case) that Gov. Rick Perry readily signed into law. Even Judge Michael Keasler – who indicated that he found the circumstantial evidence against Skinner compelling – appeared frustrated by Mitchell's insistence that fault could be still legally be found and used as a way to deny Skinner access to DNA testing. "This is not anything that popped up right now," he noted, since Skinner has been asking for this same testing since 2001. "You ought to be sure before you strap a person down and kill 'em."

Aside from several softball questions lobbed at Mitchell by Presiding Judge Sharon Keller ("Are you saying that this is one of these cases where [guilt] has been nailed down [by other evidence] and that's why we shouldn't order testing?" she asked. "Yes," Mitchell replied), the court as a whole seemed skeptical of Mitchell's arguments on behalf of a state that would have them deny the DNA testing.

Regardless the issue of fault, Mitchell argued that the "evidence of [Skinner's] guilt is unassailable." Skinner admits to being in the house at the time of the murders, but said he was passed out on a cocktail of narcotics and booze at the time of the triple slaying and awoke to find the slaughter. Then, with his hands bloodied (from touching the dead family, he said), he walked four blocks to an ex-girlfriend's house without first calling for help for Busby and her sons, and then declined medical attention for a cut found on his hand. Additionally, the state argues that Skinner confessed to an ex-girlfriend and that when he was arrested after the murders on outstanding warrants he allegedly asked police, "is that all?" leading at least Mitchell (and, perhaps, Judges Keasler and Paul Womack, who both snickered at Mitchell's delivery of the line) to believe that Skinner was surprised they weren't picking him up for the murders.

Judge Elsa Alcala seemed most skeptical of Mitchell's assurance that the circumstantial elements of the case were overwhelming evidence of Skinner's guilt that could not be assuaged by DNA evidence pointing to another person being at the scene of the crime, and in vitally close proximity to the three bloody deaths. "You're right, there's a lot of circumstantial evidence, and it's legally sufficient [to support a conviction]; no problem there," she said. "But that's not the test; you're saying it's 'overwhelming' as if he's caught on video tape killing these people. It's not overwhelming; it's circumstantial, and the question is what inference comes from that circumstantial evidence – and then the question is how would exculpatory DNA evidence affect whether that inference was rational. That's my only quarrel with you, is you're acting as if this is just so overwhelmingly concrete and it's not; it's circumstantial." DNA has exonerated people who have confessed to police – that's not the "end all, be all," Alcala noted. Indeed, Judge Cathy Cochran seemed puzzled by the state's insistent opposition to having evidence tested that could prove the state is right about Skinner's guilt. "We've had some rather embarrassing incidents in the last couple of years in which … extraordinary events have occurred [and] through the use of DNA, people have popped up and said, 'Oh my golly, here was somebody innocent in prison for all this time.' And it seemed preposterous at the time," she said. "Why not just lay this all to rest by doing the DNA quickly – after lo these 12 years – wouldn't we be better off saying, 'Phew, my goodness, there wasn't an issue here at all,' rather than leaving an issue open to concern by everybody."

There is no timeline for the court to rule, though the seeming discomfort of the judges with the state's position in the case suggested to several court-watchers that a decision could come fairly quickly.

After the hearing, Owen said he did not want to speculate about whether Skinner would receive a favorable ruling, but said it was clear the judges knew the case and what issues are in play. "They're taking very seriously the possibility that DNA testing could change a jury's mind about the case," he said.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.

Jordan Smith, Oct. 4, 2013

Jordan Smith, Aug. 9, 2013

May 22, 2014

Courts, Hank Skinner, death penalty, capital punishment, DNA, Court of Criminal Appeals, CCA, Rob Owen, Jonathan Mitchell, Elsa Alcala, Michael Keasler, Cathy Cochran, Sharon Keller