Manuel “Cowboy” Donley Lands NEA Grant

Tejano innovator wins a Heritage Fellowship worth $25,000

By Kevin Curtin, 2:00PM, Mon. Jun. 30, 2014

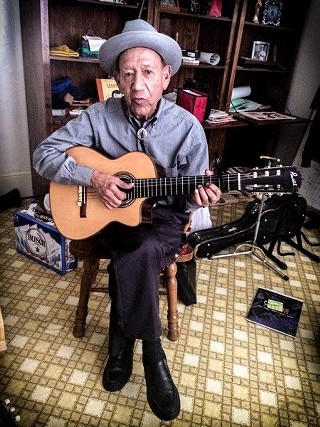

Manuel “Cowboy” Donley’s career extends back to the Forties, the 86-year-old local having helped define Tejano music with sophisticated orchestral arrangements. The National Endowment for the Arts took note and just last week awarded him the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship, a top honor that includes $25,000.

In Donley’s east Austin home old vinyl stacks high. Some LPS bear his likeness, but most favor his idols Trio Los Panchos and Chet Atkins. He can no longer read sheet music due to failing vision, but his music room remains littered with chord charts and instruments. News of his recent windfall isn’t all that unusual to Donley, who still occasionally receives royalty checks for songs he wrote decades ago.

“I’ve had two batches of kids and I never punched the clock. I raised them all with my guitar,” he states proudly. “I sent them through school on the guitar and they’re all better off than I am.”

While we discuss his life, Donley can’t help but pick up his short scale acoustic “requinto” every few minutes to illustrate a point. His callused old hands still run the fretboard better than most a third his age. Here’s an audio sample of the Cowboy:

Austin Chronicle: You were born in Mexico in 1927 and moved to Austin soon afterward. What was life like for you as a child in the Thirties?

Manuel Donley: I was too old to start kindergarten. “Yes,” “No,” and “Penny” were the only Anglo words I knew. My daddy was often gone. He was a playboy and a master violin player. He could play symphony music or any German waltz. He’d be gone for weeks, but our grandfather would give us the grocery money. There were nine of us, you see, in the depression, so if I could eat beans that was good.

I was always the slowest to the table. They thought I was retarded because I always had my own little world in my head. I’d let them all eat and sometimes I’d get some bean soup and sometimes I didn’t get nothing, but I’d go outside and I knew every peach tree and plum tree and when I wanted some meat I could really shoot a slingshot and get me a dove. They were juicy.

AC: How did you start playing music?

MD: I was a gifted artist. My teacher in Catholic school caught me drawing when we were supposed to be studying lessons. I thought she was going to hit my hands with a ruler until I cried. She said, “Manuel I want to talk to you,” and I said, “Uh oh.” She said, “Don’t you know, Manuel, that with what you know, you don’t have to learn nothing more. You’ll have all the money you’ll ever want just doing what you already know.”

So I got a job in Tarrytown painting toys, painting the eyes and face. I could look at something one time and draw it perfectly. I was working in Miss Lala Lay’s studio and I heard this on the radio. [Donley picks up the guitar and plays something resembling jug band music]. I said, “What is that?” She said, “It’s a guitar.” It was a radio program called Just Plain Bill. I’d wait for it every evening just to hear the intro and it got to me.

I went and got another job washing dishes at El Torro at 16th and LaVaca for $9 a week and bought a broken down guitar. The rest was history.

AC: Do you remember your first show?

MD: I must have been a good 15 years old and I knew two chords, D and A7. We were out on 12th and Chicon, which was the main part of the Eastside. We went into this place called the Rock Inn and the black people said, “Play something, play something!” My friend was singing like hell and I was banging on the guitar. I thought I was god’s gift to the instrument. They started throwing pennies at us and we must have made 10 cents and that was money, believe me! That was my first professional gig.

AC: Given that you’ve lived on the Eastside your entire life, does it make you sad to see the Mexican bars on East Sixth and Cesar Chavez turning into white establishments?

MD: Oh yeah, that’s where I got my education. Before I started my band, I was butting in with all the conjuntos just because I knew the latest songs. Same as with painting. If I heard a song once, I could remember it.

AC Tell me about the contributions to Texas music that you made with Los Heartbreakers and Las Estrellas?

MD: We took the romantic boleros from trios that were very popular in Mexico and put in an orchestra background. That was my idea. Then we blended in instrumental polkas and rock & roll. People had never heard or seen anything like it. We didn’t sit down like the usual bandstand style. We stood up and people had never heard things like our loud drummer or electric bass. Everyone around here used the bull fiddle, and we had three horns that were loud and blended like mad and I was playing guitar and showing off quite a bit.

AC: How were you able to write the orchestral arrangements with your limited education?

MD: All the popular Mexican ballads that were sophisticated and used harmony, nobody here could play that. Mexicans here were still playing the music from the Twenties and Thirties. I learned how to make the arrangements on a guitar. I learned the notes thoroughly: beyond the triads, the sixth, the dominant seventh, the flatted ninth, and so on. Then I learned how to put it on paper. I taught myself all the way.

AC: Can you listen to other Mexican musicians in Texas and hear your own influence?

MD: Well in a way yeah, but I don’t hear the dissonance and the harmony that I use. They don’t know that much, but they try. People tell me they’re still trying to figure out my progressions. They’re playing simple rancheras. It’s not as complicated with the voicings, just the one, four, and five chords. That’s not much music.

AC: When people say you’re the godfather of Tejano music, what does that imply?

MD: Well it means I started something and I think I did because the only big artist who did it before me was Beto Villa, but he had the soft instrumental, big band orchestra, in the Glenn Miller style except they’d play “Polka Monterrey.” We were a band that stood up and played loud with the sophisticated arrangements and new sounds.

AC: How many records have you put out?

MD: I would guess over 200 easy, including singles. I’ve recorded for 16 different labels and for just one I recorded a good 150 records. I wish I had half of my collection, but you know I was happy-go-lucky and I used to have my station wagon full of albums. I’d go traveling and come back empty. I’d sell every one of them.

AC: Did drugs and alcohol ever have an effect on your career?

MD: [Cocaine] was always around. The guys would say, “Come on, Cowboy, I have a straw for you,” and I’d make an excuse: “I have to go see the promoter guy. I don’t want him to leave without paying me. Give my straw to somebody else.” I never got into it and that’s why I’m still here. Maybe one time I did it and blew out instead of in.

At times, my musicians started carrying a lot of that stuff like coke, pills, acid, and some of them didn’t make it. They passed away. I never even finish a beer. They just sit there and get hot. My main concern has always been music.

AC: How did you feel when you found out you won the National Heritage Fellowship?

MD: I felt alright, but sometimes I just wonder if they picked me because I’m old. I would like to think they chose me because the work I put into music. I’m just a musician from East Austin and I’ve had players from Carnegie Hall ask me to teach them my stuff. That makes me feel like I might know more than they do.

AC: What are you going to do with the $25,000 that comes with the award?

MD: I never handle money. My wife handles all my business. I asked her what she wants and she said her van’s already three or four years old. I said, “You want a new one? Go for it.” She does all the work, shouldn’t she be able to spend it?

AC: You’re not thinking about a new guitar or anything?

MD: I have the best guitars in the world! That’s all my treasure. I have everything I need and then some. I never in my wildest dreams thought I was going to have these guitars. For a guy that wasn’t born here and doesn’t even have an education to have a closet full of beautiful guitars, isn’t that a dream come true?

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.

Raoul Hernandez, July 13, 2012

June 28, 2024

June 14, 2024

Manuel Cowboy Donley, National Endowment for the Arts, National Heritage Fellowship, Trio Los Panchos, Chet Atkins, Los Heartbreakers, Las Estrellas, Beto Villa, Glenn Miller, Miss Lala Lay, Rock Inn