Imaginary Television

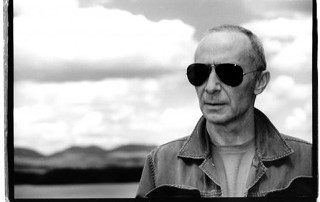

A conversation with Graham Parker

By Jim Caligiuri, 11:33AM, Wed. May 5, 2010

In the 1970s, Graham Parker emerged as one of the "angry young men" of British rock, often pigeonholed with Elvis Costello and Joe Jackson, songwriters with distinctive, passionate songwriting styles who all emerged to around the same time.

His early work with the Rumour remains some of the most affecting rock ever made. Since then Parker has bounced from label to label with 1980s albums like Another Grey Area and The Mona Lisa’s Sister bringing him his greatest commercial success.

Friday night Parker appears solo at the Cactus Café. Aside from a SXSW appearance a couple of years ago, Parker hasn’t visited Austin much of late, although he claims he played the Cactus sometime in the 1990s. He’s touring behind his fourth disc for Bloodshot Records, Imaginary Television, a concept album of a different sort.

Parker was asked to write a couple of theme songs for television shows. When rejection notices followed, the New York-based songwriter had an idea. In his bio he writes: “Enough of this, I thought, and went off to write treatments to my own imaginary TV shows, which I would grace with the correct theme tunes, not ones chosen by idiots. (Instead of lyrics on the album cover, you get plots!) In the end, he’s composed some of his most potent work in years and the witty "treatments" provided in the liner notes almost surpass the songs.

Geezerville: How did you get associated with Bloodshot Records?

Graham Parker: I was with Razor and Tie for a while there. That seemed to be wearing thin to me, so I wasn’t sure what to do. It literally came from being in Chicago, where they’re based, during this benefit concert that used to happen every year for homeless kids. Lots of names, I can’t remember the name, but it was a good benefit to do. I had just met some of the Bloodshot artists there, including Sally Timms. I was talking to her and I said, “I don’t know what I’m going to do next with a record company. It’s such a pain.” She said, "If you have something that has a country bent to it, you might want to think of Bloodshot." That kind of stuck in my head and I happened to have a bunch of songs – basically I had enough songs for two albums, and one of them became Your Country. So that seemed like a complete setup to me. I made the record and sent it to them and within a week they got back to me and said, “We love it.” Their enthusiasm was definitely genuine. With all my records for them, I record it and send to them and ask, “Do you want it?” And every time they said, "Yes, this is great.” So that’s the way our arrangement works.

G: So it’s a bit different than past labels you’ve had problems with.

GP: Lots of that is mythology. The Mercury thing, I was pretty astonished to find myself 25 years old with a record deal with Phonogram and Mercury just happened to be the American branch and touring around America in the first year of my career, albeit in a station wagon with a bunch of guys and a manager with stuff tied to the top. The road crew was one roadie who had a Ryder truck. But I was going to astonishing places for an English guy from the country suburbs. The Mercury thing, my manager was much more upset than I was. He knew a bit about the music business and realized they were doing nothing. But it was apparent you could see their staff were very old people, which means they were in their forties. To me, that was like, “Wow these people are really fucking old. They don’t understand guys that don’t look like Journey or something.” There was no punk rock then, which people forget, but there wasn’t in ’76. There was no New Wave, there was no way to market Graham Parker and the Rumour. So, basically, they really didn’t do anything. But what I’ve always been able to do is make my own records and do them under my terms. My manager, one smart thing he did, there was nothing in the contract saying they were going to listen to anything, that they would approve. Nothing like that. I just got their money, and large sums of it, more and more every year, and I made the records I wanted to make, used the producers I wanted. Because there was this song called “Mercury Poisoning,” people really paint this picture of me having all these troubles. Then they extrapolate that they were artistic problems. There was none of that. Literally, I went from one big record company to the next getting more and more money and I had a great time.

G: I thought you had some problems with RCA when you were with them.

GP: No, I had a great time with RCA because I signed with them. Here’s what happened just before I signed with them: My second manager, my manager in the 1980s, decided to put it in the contract that I should work with the label. He thought this would be a great idea. “Let’s try and work with the label, Graham. You never do, you never have. Let’s see what that does.” I was with Atlantic and never made a record for them. So I went with RCA, and I said, “Here’s what you put in the deal. They won’t hear anything, they’ll give me some money and it’ll be much less than a major record deal is now. Give me half of that and let me be free.” Then I made The Mona Lisa’s Sister, submitted it, and the first thing I got back from the head honcho was, “I spent a week with The Mona Lisa’s Sister and I think we’re in love.” That was a record with four instruments on it and the most simple drum sounds. I never had problems with RCA. I made four records with them and I did what I wanted. Then it finished and I realized that the major labels were over. The writing was on the wall that they weren’t really going to promote an act like me.

G: You’re working with Primary Wave, a publishing company that’s pitching your songs to TV and other media. They’ve actually accomplished that, correct?

GP: They’ve got me on a few TV shows. What they also did was have me re-record some of my old songs so that you own the master rights, which I did. They picked out a bunch of really old things and I picked some of the more mid-period stuff, which I think is way more commercial than any of my old stuff, I was proved right, actually. One of the songs from a 2001 record got used on a TV show recently and I got a nice bump from it. So they’re doing very well for me in that sense. But this album started because of music supervisors looking for songs that were literally going to work with TV shows. I tried and they got rejected, which I thought was pretty much par for the course. But that's what set me off writing my own TV show treatments.

G: I listened to the record first, then went to read what you had written about them in the booklet, and I thought these are just as good as the record.

GP: I was meeting with Primary Wave the other day and one of their staff said she sent the plots and the album to Judd Apatow’s people and all these hip sort of directors because maybe they’d make it into a show. I said, “Of course! That’s the way to go.” It’s not going to happen in my dreams, but that’s the logical chain of events here, man. C’mon, wake up people. There are people that realize CD sales are in the toilet, but songs don’t die, they transcend the marketplace.

G: I read what you wrote on your website about what people view as a sellout. You don’t see it that way.

GP: My facetious take. Let me tell you something: Way back in 1963 or '64, the early days of television for English kids – I was about 13 – the Beatles and the Stones happened, which is basically why I realized I should pick up a guitar in the first place. On television one day there was a Rice Krispies advert and the music sounded suspiciously like the Rolling Stones. It was a Rolling Stones song but it was, “Wake up in the morning with a crackle in my plate. Get up and go. Rice Krispies.” Me and my friends were like, "Is that the Stones?" Of course there was no way of finding out. But Andrew Loog Oldham had encouraged them to write a song for Rice Krispies. If you look up on YouTube you’ll find it. I found it one day and was astonished. I always thought that was the coolest thing. What a great way to subvert the establishment by being on adverts. I watch TV, that’s my favorite medium. I did go through long periods where music was the medium. In the hippie days with albums, even back in the day when singles were the thing, TV was my favorite medium. So to me, it’s never been a sellout to get your songs used and make money from it in that way. It’s always seemed the most natural and the best thing you could possibly do.

G: It’s kind of turned upside down these days. Look at the Who – their music is all over the place on TV and John Mellencamp had a hit because his song was used on that Chevy commercial.

GP: I bought an album by Feist, The Reminder, because of the song on the iPod ad. Now, for a lot of people, if your career doesn’t start on an advert, you might not get a career. But also it’s extremely hard to get on television. It’s either something viewed as alternative by music directors or something super-commercial like the Who. That makes it hard for artists like me. They don’t want anything too clever, it’s got to be familiar or quirky.

G: Did you write the blurbs before you wrote the songs on the album?

GP: What I did was write very rough sketches, or I had them in my head. Something like “1st Responder,” I had the idea for a sort of My Name Is Earl-type character living in a trailer with a 14-year-old son who steals cars. That came to me in flash, then I wrote the song. After I recorded the album I went back and wrote it out properly. But they were sketches of television shows.

G: The only cover is “More Questions Than Answers,” a song by Johnny Nash. How did that fit in with what you were trying to do?

GP: After about two months, I kind of got lazy. Typical of me, I thought, “Ok, I’ve done enough work.” I’ve wanted to do that Johnny Nash song forever. It must have been that I was playing it while I was writing songs every day. I have some standard or some cover that I play to get my creative juices going. I just thought stylistically it would work because the record is an eclectic pop record.

G: That made me go look for information on him. He’s originally from Texas although he’s probably remembered as a reggae artist.

GP: I thought he was from Jamaica. All those discs were reggae. He got into ska and bluebeat and went to Jamaica. Then he got hooked up with Bob Marley. I looked it up too and found out he’s from Houston, Texas. That was astonishing to me.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.