Macbeth's Myriad of Misfortunes

The Scottish Play – still cursed after all these years

By Robert Faires, 4:15PM, Fri. Nov. 2, 2018

Having two separate productions of Macbeth running in Austin this week called to mind a similar instance in October of 2000. Then, the Chronicle ran not only a feature on the play but also one on the curse said to surround the play. As the article on the curse still draws thousands of readers 18 years later, this seemed an ideal time to update it.

What follows is much of the text of the original feature, with some elaborations on the original entries, as well as a few corrections and additions.

The lore surrounding Macbeth and its supernatural power begins with the play's creation in 1606. According to some, William Shakespeare wrote the tragedy to ingratiate himself to King James I, who had succeeded Elizabeth I only a few years before. In addition to setting the play on James' home turf, Scotland, Will chose to give a nod to one of the monarch's pet subjects, demonology (James had written a book on the subject that became a popular tool for identifying witches in the 17th century). Shakespeare incorporated a trio of spell-casting women into the drama and gave them a set of spooky incantations to recite. Alas, the story goes that the spells Will included in Macbeth were lifted from an authentic black-magic ritual and that their public display did not please the folks for whom these incantations were sacred. Therefore, they retaliated with a curse on the show and all its productions.

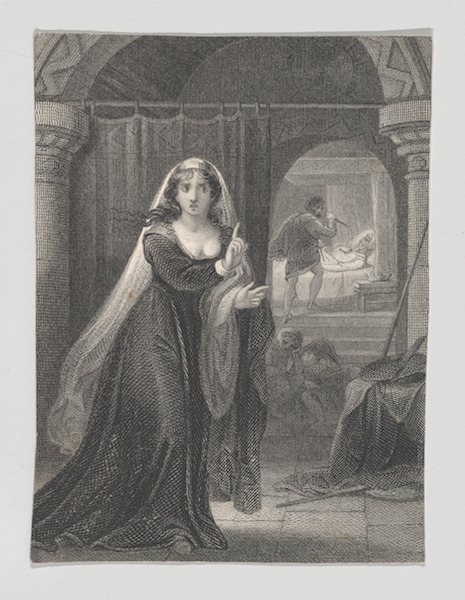

Those doing the cursing must have gotten an advance copy of the script or caught a rehearsal because legend has it that the play's infamous ill luck set in with its very first performance. John Aubrey, who supposedly knew some of the men who performed with Shakespeare back in the day, has left us with the report that a boy named Hal Berridge was to play Lady Macbeth at the play's opening on August 7, 1606. Unfortunately, he was stricken with a sudden fever and died. It fell to the playwright himself to step into the role.

This tale has been debunked as the fabrication of English critic Max Beerbohm, who included it in an 1898 review and ascribed it to Aubrey. But whether or not the curse made its debut at the tragedy's premiere, something appears to have afflicted Macbeth from the start. It's been suggested that James was not that thrilled with the play, as the next record of a performance was five years later.

Indeed, Macbeth was not performed much at all in the century after, and when it was, the results were often calamitous. The play is believed to have been first produced outside England in Amsterdam in 1672, and the story goes that the actor running the company chose to present Macbeth's murder of King Duncan on stage instead of off, as Shakespeare wrote it. As he was playing the title role himself and had become intimate with the wife of the actor playing Duncan, a genuine enmity arose between this Scottish lord and his king, and one night, he brought a real dagger onstage and dispatched Duncan for real.

Back in London at about the same time, a real blade also ended in a real death during a performance. The Duke's Men – the only company licensed by Charles II to perform Macbeth at the time – were performing the play in the early 1670s and came to the climactic duel between Macbeth and Macduff. Actor Henry Harris, playing the man not of woman born, accidentally ran his sword through the eye of the actor playing Macbeth, killing him.

When a revival of the play opened in November 1703, southern and central England were hit with the equivalent of a Category 2 hurricane that toppled 2,000 chimneys in London, caused a million pounds in damage and killed 1,500 seamen.

As time wore on, the catastrophes associated with the play kept piling up like Macbeth's victims. At a performance of the play in 1721, a nobleman who was watching the show from the stage decided to get up in the middle of a scene, walk across the stage, and talk to a friend. The actors, upset by this, drew their swords and drove the nobleman and his friends from the theatre. Unfortunately for them, the noblemen returned with the militia and burned the theatre down. In 1775, the actress playing Lady Macbeth fell ill and a 21-year-old Sarah Siddons was forced to take over the role with one day's notice; with so little time to prepare, she gave a dismal performance and was nearly ravaged by a disapproving audience.

It was Macbeth that was being performed inside the Astor Place Opera House the night of May 10, 1849, when a crowd of more than 10,000 New Yorkers gathered to protest the appearance of British actor William Charles Macready. (He was engaged in a bitter public feud with an American actor, Edwin Forrest, who was also starring in a production of Macbeth just a few blocks away.) The protest led the mayor to call out the militia, and as the protest escalated into a riot, troops fired into the crowd, killing at least 22 people, wounding 48, and injuring hundreds. And it was Macbeth that Abraham Lincoln chose to take with him on board the River Queen on the Potomac River on the afternoon of April 9, 1865. The president was reading passages aloud to a party of friends, passages which happened to follow the scene in which Duncan is assassinated. Within a week, Lincoln himself was dead by a murderer's hand.

In the last 150 years, the curse seems to have confined its mayhem to theatre people engaged in productions of the play.

In 1882, on the closing night of one production, an actor named J.H. Barnes was engaged in a scene of swordplay with an actor named William Rignold when Barnes accidentally thrust his sword directly into Rignold's chest. Fortunately, a doctor was in attendance, but the wound was supposedly rather serious.

A production at the Prince's Theatre in 1926 was already beset by stolen equipment, falling scenery, and costumes catching fire when its lead actor, Henry Ainley, had to leave the show from nervous exhaustion. But his burly replacement, Hubert Carter, had so little physical control that he nearly strangled his Lady M, Sybil Thorndike, in the throne scene.

During the rehearsal period for the first modern-dress production at the Royal Court Theatre in London in 1928, a large set fell down, injuring some members of the cast seriously, and a fire broke out in the dress circle the Sunday before opening.

In a 1934 production at the Old Vic, the show's Macbeth, Malcolm Keen, suddenly lost his voice during an early performance and was replaced by Alistair Sim. But very quickly Sim developed a severe chill and had to be hospitalized, so he was replaced by Marius Goring, who filled in until a fourth actor, John Laurie, could be brought in to take over the role. This all took place within a week's time.

In 1936, when 20-year-old Orson Welles produced his "voodoo Macbeth," set in 19th-century Haiti, his cast included some African drummers familiar with "white magic" practices from their cultures. As Welles told the story, they were not happy when Herald Tribune critic Percy Hammond blasted the show, and Abdul Assen, who was cast as the Witch Doctor in the production, approached the young director about making "beri-beri" on the offending journalist. When Welles told him to go ahead, Assen started a drumming ritual. Hammond died just over a week later.

In 1937, at the Old Vic, a 30-year-old Laurence Olivier was preparing to play Macbeth for the first time when the director, Michael St. Denis, and Vera Lindsay, who was playing Lady Macduff, were involved in a car accident on the way to the theatre. Two days later, the dog belonging to the Old Vic's founder, theatrical grande dame Lilian Boylis, was run over by a car. Then a stressed-out Olivier caught a cold and lost his voice, forcing the postponement of the opening, and St. Denis was replaced as director by Tyrone Guthrie, who had three days to get the show ready to open. In that brief period, a 25-pound stage weight crashed down from the flies, missing Olivier by inches. Then, Baylis took ill and died of a heart attack just before the final dress rehearsal. The next time Macbeth was produced at the Old Vic, 17 years later, the portrait of Baylis that was hung in the theatre fell from the wall on opening night.

When she directed a production of the play in 1940, Margaret Webster suffered from appendicitis; had to fill in for her Lady Macbeth, Judith Anderson, when she was stricken with laryngitis; and then just before the production was to be performed for the U.S. Army, came down with acute tonsilitis.

In 1942, a production headed by John Gielgud suffered three deaths in the cast – the actor playing Duncan and two of the actresses playing the Weird Sisters, one of whom collapsed onstage – and the suicide of the costume and set designer, John Minton.

In 1947, actor Harold Norman was stabbed in the swordfight that ends the play and died as a result of his wounds. His ghost is said to haunt the Colliseum Theatre in Oldham, where the fatal blow was struck. Supposedly, his spirit appears on Thursdays, the day he was killed.

In 1948, Diana Wynard was playing Lady Macbeth at Stratford and decided to play the sleepwalking scene with her eyes closed; on opening night, before a full audience, she walked right off the stage, falling 15 feet. Amazingly, she picked herself up and finished the show.

In 1953, Charlton Heston starred in an open-air production in Bermuda. First, the actor was badly injured in a motorcycle accident during rehearsals. Then, on opening night, Heston suffered severe burns in his groin and leg area from tights that were accidentally soaked in kerosene. The wind that night was so strong that when a dummy representing Lady Macbeth was tossed off the rampart to show her leaping to her death, it was blown right back onto the rampart, and smoke and flames from torches carried by the soldiers storming Macbeth's castle were blown into the audience, which ran away in a panic.

In 1955, Olivier was starring in the title role in a pioneering production at Stratford and during the big fight with Macduff almost blinded fellow actor Keith Michell.

In a production in St. Paul, Minn., in 1970, actor George Ostroska was playing Macbeth dropped dead of heart failure during the first scene of Act II.

In 1988, the Broadway production starring Glenda Jackson and Christoper Plummer is supposed to have gone through three directors, five Macduffs, six cast changes, six stage managers, two set designers, two lighting designers, 26 bouts of flu, torn ligaments, and groin injuries. (The numbers vary in some reports.)

In 1998, in the Off-Broadway production starring Alec Baldwin and Angela Bassett, Baldwin somehow sliced open the hand of his Macduff.

Add to these the long list of actors, from Lionel Barrymore in the 1920s to Kelsey Grammer in 2000, who have attempted the play only to be savaged by critics as merciless as the Scottish lord himself.

To many theatre people, the curse extends beyond productions of the play itself. Simply saying the name of the play in a theatre invites disaster. (You're free to say it all you want outside theatres; the curse doesn't apply.) The traditional way around this is to refer to the play by one of its many nicknames: "the Scottish Play," "the Scottish Tragedy," "the Scottish Business," "the Comedy of Glamis," "the Unmentionable," or just "That Play." If you do happen to speak the unspeakable title while in a theatre, you are supposed to take immediate action to dispel the curse lest it bring ruin on whatever production is up or about to go up. The most familiar way, as seen in the Ronald Harwood play and film The Dresser, is for the person who spoke the offending word to leave the room, turn around three times to the right, spit on the ground or over each shoulder, then knock on the door of the room and ask for permission to re-enter it. Variations involve leaving the theatre completely to perform the ritual and saying the foulest word you can think of before knocking and asking for permission to re-enter. Some say you can also banish the evils brought on by the curse simply by yelling a stream of obscenities or mumbling the phrase "Thrice around the circle bound, Evil sink into the ground." Or you can turn to Will himself for assistance and cleanse the air with a quotation from Hamlet:

"Angels and Ministers of Grace defend us!

Be thou a spirit of health or goblin damn'd,

Being with thee airs from heaven or blasts from hell,

Be thy intents wicked or charitable,

Thou comest in such a questionable shape that I will speak to thee."

For additional reference on the Macbeth curse, see Richard Huggett's The Curse of Macbeth and Other Theatrical Superstitions (Picton Publishing, 1981).

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.

Richard Whittaker, April 5, 2020

Richard Whittaker, Jan. 13, 2020

Sept. 24, 2021

Sept. 17, 2021

supernatural, Macbeth curse, William Shakespeare, Astor Place riots