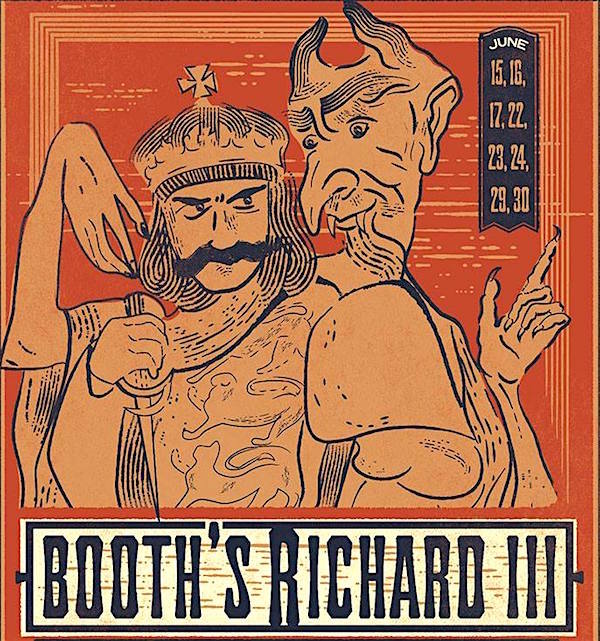

The Hidden Room Theatre Is Working With a Presidential Assassin

Aside from that, Mrs. Lincoln, we reckon you’ll really enjoy the show

By Wayne Alan Brenner, 7:00AM, Tue. Jun. 12, 2018

Austin’s Hidden Room theatre company is officially in cahoots with John Wilkes Booth, the actor who shot and killed President Abraham Lincoln back in 1865. They’re engaged in a sort of transtemporal collaboration, of course, and the Ransom Center’s Eric Colleary is partly to blame.

But, because what’s actually happening is a period-specific presentation of Shakespeare’s Richard III, based on Booth’s promptbook from the 1860s, no one is likely to be killed this time.

Hell, Judd Farris – cast in the titular role – might not even bleed all over the floor this time.

But there will be bleeding of a sort – a chronological bleeding, as theatrical methods and manners of the late 19th century inform the production, and the basic script is the forgotten Restoration version of the Bard’s dark drama, and who knows what odd resonances might be struck within the Scottish Rite Theatre where the violent tragedy will play out, night after night, over three of our ever-so-modern weekends.

You know Beth Burns and her company have been bringing us this kind of thing for a while now, right? That the Hidden Room specializes in re-creating classic theatre very much the way it was staged back in the day – depending on which “day” they’re going for at the time.

Thus, the enhanced puppet-show spectacle of Der Bestrafte Brudermord – that production in which Judd Farris did bleed, unintentionally lacerated, all over the floor. (Seriously: There was a fucking puddle.)

Thus, the gesturally enriched, Restoration-flavored King Lear gallivanting all over the York Rite ballroom.

Thus, even, the contentious (and highly compelling) lecture-circuit posturings of Arthur Conan Doyle and the erstwhile Erich Weiss in Houdini Speaks to the Living.

Note: They’re not just making shit up here, people. Beth Burns hasn’t presented her Shakespearean stuff at Oxford, for instance, because she’s just pulling it out of her aspidistra. There’s an impressive amount of research involved in these endeavors, plenty of what they call scholarship going on.

Which is where Eric Colleary and the prodigious archives of the Harry Ransom Center often come into play. In fact, a discovery of Colleary’s is what one could call the inciting incident of this newest adventure in stagework.

“I’ve been here for almost three years now,” says Colleary, who is the HRC’s Cline Curator of Theatre and Performing Arts, “and one of the first projects I was working on was an exhibition celebrating the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare in performance. And so I was trying to find records that would show the history of Shakespeare being performed over 400 years. And I was really surprised to find that we had this promptbook that was used by John Wilkes Booth.

“A promptbook,” he clarifies, “is a script that has all of the show’s notations. And this is not just the actor’s promptbook, because this was Booth’s production – he was also the director – this is the show he toured around the United States – and it’s the best record we have of what his theatre looked like. It’s an incredible historical document, from somewhere between 1860 and 1863. It’s this really important moment in American theatre history, because the theatre is actually changing a lot at the moment – more people are going than ever before, the technology of the theatre is changing, and the acting styles are changing. What people like is changing. And then you have John Wilkes Booth, who is an immediately recognizable figure, even for people who have no background in theatre history: They’ll know who he is.”

And Colleary, fresh off a plane from Minnesota, knew who Beth Burns is.

“I met Beth when I first came here,” he says, “and I knew some of the work that she was doing. She’d just done Brudermord, and was getting ready to do King Lear. And that was such a surprising thing for me to find here in Texas: That there was a really talented, savvy theatre company that could take a work like this and bring it to life – in a way that wouldn’t be just, like, academic and dry and scholarly – which would be awful – but actually take that scholarship and honor it, make it really engaging, make it something that audiences want to see.”

So, as part of that "400 Years of Shakespeare" exhibit, Burns and Colleary staged a one-night-only reading of Booth’s Richard III.

“And we costumed it as if it had been a rehearsal of that period,” says Burns.

“All the performers were in accurate dress for the time,” says Colleary. “And it went really well, and the response to it was incredible – especially from people who teach Shakespeare. Because this is not Shakespeare’s Richard III, this is Colley Cibber – who did a Restoration adaptation of the play in 1699. And then, for over 200 years, this is the Richard III that every audience saw. For the bulk of the time, since Shakespeare’s death and our present, this version is what everybody knew. But now, we never see the Colley Cibber version any more – and Booth’s editing of the script has not been seen since 1863.”

“One of the things I’d always wanted to do when we started Hidden Room,” says Burns, “I wanted to find a promptbook – very much like this one Eric found – with all the stage directions, and then research the theatre practices at the time, and see if we could make our own little time machine as best we can, to crank it up and see if we could bring back the ghost of a play. And I’d never found quite the right script. Because the farther back in time you go, the less you know – the less instruction there is, the less detailed the promptbooks are. Sometimes there’s just a couple of Xs and Os, if you’re lucky. But this show’s book had really specific notes from Booth in it, had specific blocking and diagrams and costumes. And it included reviews, as well. And I thought, What better thing to help an audience want to come see a re-creation like this, than having a notorious villain at the helm?”

Austin Chronicle: Yeah, people do love their villains.

Burns: And getting to not glorify Booth, but to humanize him – realizing that he was popular at the time, that he was charismatic, that people described him, contemporaneously, as a gentle, kind person.

Colleary: And very handsome.

Burns: And very handsome! And it’s just a good reminder that even very popular people can do terrible, terrible things – and can get radicalized when political discussion becomes too divisive, too heated and unchecked. That’s how you divide a nation.

Austin Chronicle: So, the assassination, it’d be like – George Clooney shooting President Trump?

Burns: Well, it was Lincoln. So it’d be more like Brad Pitt shooting President Obama.

Austin Chronicle: Ah, yeah, good point.

“And this show was the perfect combination,” says Burns. “It’s a play with an incredibly detailed promptbook, with a production that we actually know something about. We have a black-and-white film – done in 1911, I think – which is from a production that had been running since the 1800s, so that gives us more of a sense of what their style may have looked like. And we have a wax cylinder of Edwin Booth performing – that’s John’s brother, who was also a wildly popular actor – as an example of what the vocal technique may have sounded like.”

Austin Chronicle: It’s good to be in the same town as the Ransom Center.

Burns: Oh, yes. Yes, it is. And, with all these things in place, I thought “Here’s my time machine!” I’m training the actors using extant theatrical handbooks and acting books that Eric’s provided – we’re using actual technique approaches from those books. And we’re using a make-up book, to use actual make-up from that period, and using Eric’s research into costuming of the time, to construct the costumes.

Austin Chronicle: And you’re staging this thing in the Scottish Rite.

Burns: With the scholarship of Susan Gayle Todd, who’s been taking great care to keep that theatre in order, to restore it and treat it well – and help fill us in on how the theatre may have run back then. It’s a theatre that has its own 19th-century technology already built in, including a thunder run – which is incredibly rare.

Austin Chronicle: A … thunder run?

Burns: A thunder run is a special trough that’s up in the ceiling. The one at Scottish Rite runs along the backstage, but some of them run all the way up into the theatre. You drop a couple of birch balls into them and they roll to make a rumbling thunder sound. And there’s an extant wind machine – that people thought, at some point, was just a Bingo machine? And there’s an extant prompter station, so our prompter won’t be using headsets or anything like that – he’ll be using the prompter’s whistle around his neck, and the prompter’s bell around his wrist, to call up musicians and scene changes.

Colleary: Part of the research was deciphering what a 19th-century promptbook looks like, what the often cryptic instructions mean. Like, there’s a W where you’d whistle for scene changes. Which, by the way, is why it’s bad luck to whistle on stage – because they used to use actual whistles. The theatre season was usually in the winter, which was the off-season for shipping, so the people who did rigging on boats or on docks – to get cargo off or onto the ship – they’d use whistles and ropes there, and then they’d get jobs in the theatre during the off season. And that’s how the system got into the theatre.

Austin Chronicle: Damn, man. These Hidden Room productions – I mean, you guys really go deep.

“What Beth is doing,” says Colleary, nodding agreement, “it activates the Ransom Center’s collection in a really exciting way. You could just read the promptbook, and you’d get some important things about it. But you’ll learn so much more from actually seeing it, from it being embodied on the stage.”

And if you’d like to see the Hidden Room production of the John Wilkes Booth version of the Colley Cibber adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Richard III embodied on the stage, citizen, you can reserve tickets by clicking right here.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.