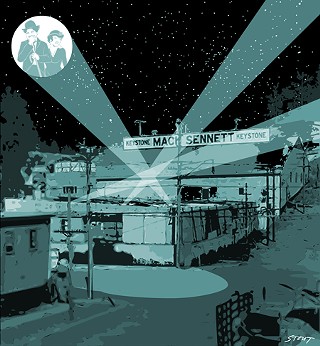

Letters at 3AM: Shindig on Effie Street

The silent film comedians at Keystone Films lived their art

By Michael Ventura, Fri., Dec. 17, 2010

Effie Street dead-ends a block west of Glendale Boulevard at a hill too steep to pave. At the dead end, a switchback stairway goes straight up the hillside. I climbed those stairs and stopped at a landing. I held a folder of photographs. The most important, Glendale Boulevard 1905, showed the very view I now saw, as it was a century before. This photo was taken by Coy Watson Sr., later an important special-effects innovator for Mack Sennett and Douglas Fairbanks. Why Watson took that photograph I have no idea. In 1905, Watson could not know he'd photographed one of the most important sites in the history of silent cinema.

Also in Watson's 1905 photo is an isolated one-story building. Its sign reads: "Edendale Grocery." Edendale, then, was a rural village just northwest of what is now downtown Los Angeles.

Standing on that landing, I saw, on Aaron Street, a block north of Effie, a house in the 1905 photo that is also in later photos of Mack Sennett's Keystone Pictures Studio. The same attic, the same windows. The only difference is that a second-story porch has been enclosed to make a room. Otherwise, that house has hardly changed in a century.

Now I had two reference points. On Aaron, that century-old house. And on Effie, east of Glendale Boulevard, the concrete structure Mack Sennett built in June 1915 still stands, serving today as a U-Haul storage facility. Using that house and that building, I could lay out my Keystone photos and figure where just about everything was. For instance, if you go into the Jack in the Box on Glendale between Effie and Aaron and sit at a table on its north side, you're probably at the site of the dressing room of cinema's first great comedienne, Mabel Normand.

In a 1912 photo, the building that had been Edendale's grocery sports a painted sign: "Broncho and Keystone Film Companies." Mack Sennett, Mabel Normand, and their troupe headquartered there. That same one-story wood frame, with a new awning, is the featured exterior in Sennett's comedy "That Ragtime Band," which was released May 1, 1913. In the film, you see clearly that, as of May 1913, the Keystone Studio had not yet been built. Sennett's venture was still a week-to-week affair, uncertain of survival.

A photo taken early in 1914 shows Keystone's growth: a ramshackle place, hastily patched together around the old grocery store and a cottage about 50 yards north. There's an open-air stage, roofed and walled with muslin "defusers," as they were called, to spread sunlight and minimize shadows. On that stage Sennett's troupe built its interior sets. This rough place is what Charles Chaplin found when he came to Keystone late in 1913.

"It was," he wrote, "a dilapidated affair with a green fence round it, one hundred and fifty feet square. The entrance to it was up a garden path through an old bungalow. ... The studio had evidently been a farm. Mabel Normand's dressing-room was situated in an old bungalow and adjoining it was another room where the ladies of the company dressed. Across from the bungalow was what evidently had been a barn, the main dressing room for minor members of the stock company and for the Keystone Kops. I was allotted the star dressing room used by Mack Sennett, Ford Sterling, and Roscoe Arbuckle. It was another barnlike structure, which might have been the harness room."

Chaplin recalled Keystone's "he-man atmosphere" of "ex circus clowns and prizefighters." He found it intolerably vulgar, a "crude mélange of rough and tumble," justified by a "pretty dark-eyed girl named Mabel Normand. ... It was a strange and unique atmosphere of beauty and the beast."

The Keystone troupe thought Chaplin as strange as he thought them. Actress Minta Durfee remembered Chaplin as a "clever man, but he was plenty dirty." It was an era when shirts were without collars or cuffs; those were fastened on separately. Chaplin wore the same soiled collars and cuffs for days on end. During the 1914 filming of Tillie's Punctured Romance, actress Marie Dressler demanded Chaplin change a food-stained collar he'd worn all week. At Keystone, he spoke a rough Cockney accent, not the cultivated voice he later developed. He befriended no one but Mabel Normand. They studied French together. Mack Sennett wrote of Chaplin, "He was lonely and liked to be lonely" (Sennett's emphasis).

"In the beginning," Mabel Normand remembered, "we were golden lads and girls. ... We didn't know what to do with [our money] or ourselves, and we didn't care." Then as now, that was the attitude of young adventurers. When Chaplin arrived, Normand, the studio's star, was but 19 (or 20 or 21, depending on which birth date one believes). Chaplin was 24. Arbuckle was probably 25; Durfee, his wife, probably 23 (sources differ). Sennett, graying prematurely, was called the "Old Man," though he was only 33. They'd all "lived rough," as the saying went. Normand earned her own living from age 13; Chaplin, from age 8 or so; Arbuckle, from age 15; Sennett, from age 17. And they all knew the meaning of trouble. Arbuckle and Chaplin had alcoholic fathers; Chaplin, a schizophrenic mother; Normand watched four siblings die before their teens. Abandonment, betrayal, have-nothing poverty, violence (domestic and otherwise), alcoholism, flat-out madness, and the uncaring, unfair chances of fate – the stuff of their lives became the stuff of their comedies.

They did their own stunts, and none of it was faked. Arbuckle auditioned for Sennett by suddenly falling backward down a flight of stairs and bounding up at the bottom with a ballerinalike twinkle-toe hop, though he weighed more than 250 pounds. Normand biographer Betty Fussell reports that in 1915, filming "Dizzy Heights and Daring Hearts," Chester Conklin and Normand were "in a monoplane, with Chester at the controls. He was supposed to taxi on the ground, but he got excited, opened the throttle by mistake, and the plane took off. Fortunately it hit some trees and fortunately Mabel jumped before the crash." It was all in a day's work. Keystone's base pay was, according to Sennett, "five dollars a day and hospital bills."

Off-camera they behaved as they did on-camera. Conklin threatened to quit if Normand didn't stop sliding lit firecrackers at his feet while he performed. She also was known to toss firecrackers into the developing room, where their flammable nitrate-film stock could have blown the shed, those in it, and Normand herself sky-high. One day, when Sennett berated her for being late, she sat on his lap and peed. They'd mix hot mustard into someone's make-up or coat a Keystone Kop's helmet with stinky cheese that then melted onto his face in the hot sun. Sennett boasted proudly: "We lived our art."

Minta Durfee remembered her introduction to Keystone. She and Arbuckle were stranded in Los Angeles, looking for work, when they ran into Sennett's friend and cohort Fred Mace. He told them: "There's a shindig on Effie Street. You might try there." A shindig it was.

Like Chaplin, Normand, and Sennett, few Keystone players had even an eighth-grade education. Sennett said it: "There were no dukes on the Mayflower." Nobody had ever done anything like what they were doing.

Chaplin at Keystone, the new 4-disc set, presents their films wonderfully restored. Some are not laugh-aloud funny to our tastes (and some are, especially Tillie), but all bristle and spark with wildness and grace, a demonic and daemonic energy that makes you wish you were there in that raw time and place, that "cloud-cookoo land of laissez-faire and topsy-turvy" (Sennett's words), when the free, the painful, and the joyful careened into one word: slapstick.