The Future’s So Dark I Gotta Wear Mirror-Shades

Cyberpunk

By Marc Savlov, Fri., July 25, 2008

"The future masters of technology will have to be lighthearted and intelligent. The machine easily masters the grim and the dumb." – Marshall McLuhan

With apologies to Charles Dickens and Marley's money-boxed ghost, cyberpunk is dead to begin with. There is no doubt whatsoever about that. Old cyberpunk is as dead as Marley's doornail or Apple's Mac OS 9 or the mission-to-Mars space program so grandly announced, and so recently, too. You want to go to Mars, space-boy? Go read Ray Bradbury. Cyberpunk – literary, filmic, etc. – isn't going to get you there any more than Richard Branson is a virgin.

Initially a literary movement defined by a wittily jaundiced view of emergent computer technology and human interaction therewith and chronicling a steady stream of fringe-dwelling, tech-savvy human protagonists who engage in skirmishes with the Machine as well as one another, cyberpunk (the term is credited to sci-fi author Bruce Bethke) went viral almost immediately, alongside its meatier offshoot, splatterpunk. It moved beyond the printed page to encapsulate and define a grim, edge-dancing, occasionally techno-phonic world-view that in hindsight looks positively prescient.

For a while, roughly from the mid-Eighties to the late Nineties, cyberpunk's fashionable nihilism – black leather, mirror-shades, smart bars, Wired magazine – managed a rare balancing act by becoming de rigueur among the literary, cinematic, and style-conscious cognoscenti while remaining totally, mysteriously underground in less pessimistically enlightened areas. Just like its symbolic forebears the Sex Pistols and the Situationists before them, cyberpunk never quite played in Peoria.

Like all great literary and cultural movements – edgy, forward-thinking, smart, and mean – cyberpunk died a thousand deaths, not least of which was the arrival in theatres, in 1995, of Robert Longo's film adaptation of William Gibson's Johnny Mnemonic. Any genre codified in the flesh by Keanu Reeves – no matter how good the story – is doomed or, at the very least, clumsily embodied to the point of ridiculousness. You could, of course, make the argument that Reeves, who went on to play two of the most nuanced and socially relevant cyberpunk roles – Neo in The Matrix series and Bob Arctor in Richard Linklater's recent buzz-kill A Scanner Darkly – helped keep the genre alive in the minds of the Great Unwashed far longer than it would have lingered otherwise. But the final, single-tone, flat-line truth of the matter is that you simply don't hear cyberpunk-the-term being bandied about all that much anymore.

The rattle and hum and wiry thrum that you hear whisper-streaming behind the everyday white noise of human behavior is the sound of reality: omnivorous and insidious and insatiable (I like to visualize it as looking kind of like Stephen King's goofy, world-devouring Langoliers), bumping up against the futuristic fictions of cyberpunk and osmotically absorbing them whole, amoebalike, a vacillating bacillus of bad, black, 24/7 broadcast news from the front lines of the end of time. Cyberpunk's grave new worlds have become today's geopolitical and cultural battle-space. Cyberpunk's dystopian future is now, everywhere and never-where and all points in between. If you've been in any major metropolitan area in the past decade, you'd be hard-pressed not to notice that Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, with its polyglot culture crush and conspiratorial, noirish unknowability, is no longer a fiction.

The great cities of the world – New York, Los Angeles, Beijing, Mumbai, and even the real-world Tokyo of the watershed animé Akira – have mutated and metastasized in a frenzied, corporate-controlled, dystopian freak-out that's plenty fun to visit, but you wouldn't want to live there. But, of course, you do. Cyberpunkery across all disciplines has become less an easy, buzz-worthy metaphor for a viciously Homeland Security-monitored, TALON'd-and-terrifying futuristic nightmare than a convenient tech-lit label rendered obsolete in the face of a sprawling, fiber-optimized, and perpetually exploding neo-Tokyo that's running roughshod over the off-line unluckies of the Third World. Ever the steadfast, Intel-chipped tin insurgents marching resolutely into the gaping maw of an unknowable future, cyberpunk's leading literary overlords (William Gibson, Neal Stephenson, John Shirley, the late Philip K. Dick, and Austin's own roaming futurist/seer Bruce Sterling) continue to amaze and horrify with their tech-static/tech-phobic visions of a wholly globalized worldwide weird.

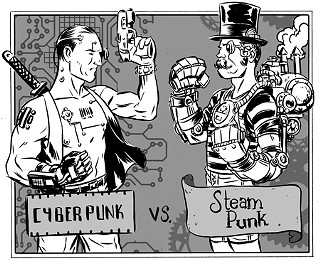

As cultural soothsayers, the cyberpunk auteurs still have their trademark long teeth and sinewy, loping legs, but the black fact of the matter is that the futurist fictioneering of Gibson's "The Gernsback Continuum" and Sterling's Zeitgeist has not only been superseded by the sort of reality mind-bombs not seen since the steampunk days of the Industrial Revolution.

Simply surfing the Usenet news posts and horny little chan-boards confirms and extrapolates the famous dictum "information wants to be free," and most anyone with a working knowledge of the Net knows that life online is often if not always more hypnotic and enthralling than anything the mundane world has offered since the Power Macintosh G3.

Those who've peeped Shinya Tsukamoto's tech-fetishistic Tetsuo or Cronenberg's Game Boy hell eXistenZ know that technology first panders to our most base desires. Fritz Lang knew it when he designed Maria, the sexiest virtual robo-babe this side of Seven of Nine, for 1927's Metropolis, and certainly the National Security Agency spooks and DARPAnet data-miners are well aware of the Net's cyber-disseminating powers. Jihad and porn make for strange bedfellows – well, not that strange when you include the 72 post-corporeal virgins scenario – but the mind- and libido-boggling popularity of their dominance over the darker corners of the Web is nothing if not a case of reality as Zemeckisized castaway, beached upon the infinite nanobot sands of those islands in the Net.

So what is cyberpunk when the whole wide world, webbed and phreaky, is suddenly looking like something out of a Roland Emmerich/Michael Bay production? It's useful as a tool, a yardstick to measure the weirdness, but even at their best, the amphetamine reptile musings of Philip K. Dick seem way too plausible – almost passé – when compared to al Jazeera's global reach and our side's unmanned Hunter drones. It's the sort of bad craziness you wish Hunter S. Thompson had been able to stick around for.

Instead we got Transmetropolitan's Spider Jerusalem, renegade gonzo journalist-cum-comic-book antihero, oozing sarcastic cynicism while trying to keep his shit together in a 2000AD kind of world. Which looks suspiciously like our own:

"Journalism is just a gun. It's only got one bullet in it, but if you aim right, that's all you need. Aim it right and you can blow a kneecap off the world." Warren Ellis' Jerusalem, just like the real one, thrives on chaos and a squirrelly sort of laptop nomadism. He wore cheaters, too, a nice gonzo touch that Thompson would've appreciated. But they're both either MIA or KIA these days, and the difference engine has been retrofitted to run on steampunk as we await the crashing of the grid, already under way.

Cyberpunk? That was now, but this is then. The artificial kid has become the demolished man.