In Person

Helena María Viramontes

By Belinda Acosta, Fri., April 20, 2007

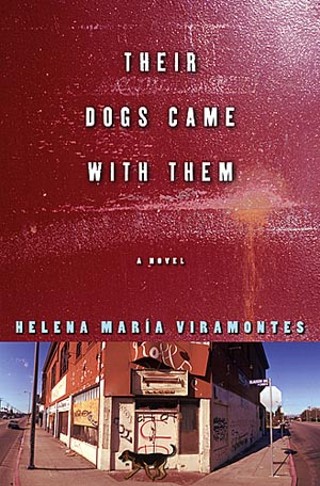

Their Dogs Came With Them is a novel, but to fully appreciate it, approach it like a mural. While the grandness of a mural is what first commands attention, the viewer enters through its image details. After which, the viewer can then step back and reflect on the whole. The same is true of Viramontes' startling second novel. Twenty-five characters take turns standing in relief, written with extraordinary precision and profound compassion.

The title comes from an account of the Mexican conquest by Miguel León-Portillo, describing the sight of conquerors overpowering the indigenous Mexicans: "Their dogs came with them ... [racing] before them, saliva dripping from their jaws." Similarly, the aggressive rise of the freeway system from 1960 to 1970, which slashed much of East L.A. (where the novel is set), provides a modern version of a different sort of conquest, where whole blocks of mostly Mexican-American homes were razed in the name of progress. What happened to the displaced, Viramontes wondered.

The León-Portillo epigraph also resonates in a provocative fictional element in the novel, a mandatory curfew caused by a rabies outbreak. Helicopters hover over the scarred neighborhoods after dark, shooting at stray dogs (or anything else) not chained, boarded, or otherwise out of sight. The rabies curfew stands in for the curfews that occurred after the Chicano Moratorium march, an event that gathered more than 30,000 Chicanos in East L.A. to protest the Vietnam War and other social injustices. The moratorium ended in police-incited violence, resulting in a "public safety" curfew. The weight of surveillance, the destruction of the old way of life, and the already turbulent political period make up the dynamic canvas from which the characters of Their Dogs Came With Them emerge. Viramontes took time to talk about her new book prior to reading at BookPeople last week.

Austin Chronicle: Descriptions of your book single out four main characters: Turtle, Ana, Ermila, and Tranquila. But they don't seem as central as the environment where the characters live, an environment that is dramatically shifting. I'm wondering if this moment of flux is another character, like a specter no one can ignore.

Helena María Viramontes: You hit one of the pulses there. There are no real main characters. [Turtle, Ana, Ermila, and Tranquila] are the orbits that the other characters circle around. I look at things very visually. What I'm really talking about is the atmosphere, the space, the geography ... and the transgression of borders: sexual, gang turf, and of East L.A. itself.

AC: You've said elsewhere you wanted to portray the lives of the "disappeared."

HMV: I heard stories about when the [freeway] 60 was going up; human bones were found because it was built over a cemetery. Call them urban legends, and maybe they are, but those stories stayed with me. I wondered what happened to those displaced people. I thought about the displacement of Chavez Ravine [in order to build Dodger Stadium], how people actually took up arms in resistance. They were defending their homes in old, well-established townships, and then to not have any control of those changes? Wow. I thought about all of that, and I wanted to capture those lost voices.

AC: You helped build Chicano literature, both in your literary and academic work, at a time when Chicano literature was both emerging and contested in the academy. Do you think the term "Chicano literature" is still meaningful nowadays?

HMV: Absolutely! In fact I was speaking to my mentor, María Herrera-Sobek who helped establish one of the first Ph.D. programs in Chicano studies. When she goes out and speaks at various universities, especially in Texas, the term "Chicano" was still being contested. People do not possess a history of what it means. Children don't learn this history in the public schools. I have no problem identifying as a Chicana writer writing Chicano literature. I also know that good literature transcends. Look at Sandra Cisneros, Benjamin Saenz, Ana Castillo, Manuel Muñoz, Junot Díaz. Our work is read all over the world. For me, I feel like [East L.A.] is like my own Faulkner territory. The more I dig down, the more I find to tell.