The Full Franklin

H.W. Brands' New Biography Reveals the Entire Story of Benjamin Franklin

By Clay Smith, Fri., Dec. 1, 2000

Who is Benjamin Franklin? The question is bizarre but necessary. Unlike George Washington, for example, Franklin was not a galvanizing, commanding military leader; he was charming and genial, a practical and approachable person who seems to have erased any taint of mystery or contradiction about himself. (He was so straightforward and revealing as to construct a diagram of virtues and rate his efforts at attaining them.) Even H.W. Brands, his most recent biographer, admits that Franklin "never was a particularly dramatic figure." Franklin has always been with us but because of the encyclopedic nature of his talents, certain aspects of his life have been picked out for review that don't reveal the entire person. In high schools across the nation, Franklin is trotted out as the man who discovered electricity, the prototypical capitalist who seems concerned with virtue merely for the sake of materially keeping up with the competition. In that light, he seems too pale-blooded to make a good founding father. His ambitions seem peculiar.

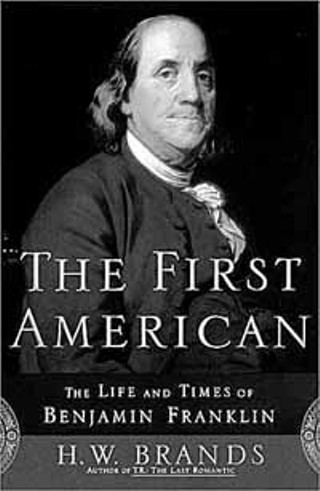

As Brands' biography, The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (Doubleday, 648 pp.,$35) attests, there's a native wealth of curiosity about a man who ran away from home in a fury of disappointment and confusion to educate himself to become, at various times, a journalist, publisher, inventor, notorious womanizer, scientist, bon vivant, postmaster general, diplomat, fire marshal, and a repeatedly reluctant politician. When Brands, who lives in Austin but is a history professor at Texas A&M University, finished writing T.R.: The Last Romantic, a biography of Theodore Roosevelt, he knew that his next subject would have to be as multifaceted as Roosevelt in order to maintain his interest. He searched around and discovered that it had been nearly 60 years since Carl Van Doren's Benjamin Franklin had been published. I asked him what it means, exactly, for his biography to be "the Franklin biography for our times." Why now?

H.W. Brands: Well, the simplest and simple-minded answer to that is now because it hadn't been done in a while. I'm not sure that Franklin is particularly more relevant to Americans in the year 2000 than he would have been, say, in the year 1985. In fact, one of the things that struck me -- and I should add -- that I didn't really go into this as a big fan of Franklin. As a historian-biographer, I'm just attracted to interesting stories. For example, I thought Theodore Roosevelt was a great story. I still have reservations about whether he was a great man. But at least it's a great story, an illuminating story. And that was the approach that I took toward Franklin originally. But I have to say I was entranced by Franklin in the course of writing the book and I think he is somebody who just has a whole lot of wisdom that in a certain respect is good for any generation. ... He was a very practical individual; he was optimistic without being Pollyanna-ish. He fully accepted human weaknesses but on the other hand he was prepared to believe that most people could rise above their weaknesses if necessary and so I think Franklin's story is something that's appropriate to any generation.

AC: Did you find during the writing process that you needed to correct any misperceptions about Franklin?

HB: Well to some degree, yeah, after I got into it because I realized that Franklin was much more critical, for example, to the success of the American Revolution than he's generally credited with being over the last, say, 40 to 50 years. Even in his day, Franklin was reckoned to be one of the two people that was most responsible for the success of the Revolution and the launching of the American republic. The other was George Washington. And even as vigorous a critic of Franklin as John Adams admitted that when the histories of the time were written, they would all see Franklin and Washington as head and shoulders above everybody else and at the time Franklin died, he was generally recognized to be the most preeminent American of his generation.

But beginning in the 1940s and 1950s, his reputation slid a little bit into decline. And partly I think this is because we've always known Franklin; he's presented in a way that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton and James Madison are not. Franklin has always been part of the required reading of every high school. To some extent, the academic history profession is like any other academic field where people want to know what's new. And Franklin wasn't really new and, in addition, there was the whole emphasis on finding voices that had gone unheard for a long time and looking at aspects of American history that had been unexplored, so there was a turning away from these icons of the Revolutionary era to people who heretofore had been nameless and faceless. And so on that ground as well, Franklin was sort of taken for granted, was sort of set aside as an interesting old fellow.

AC: In high school, I remember that all we learned about Franklin in English class was that he diagrammed his virtues. He seemed rather stuffy.

HB: Oh, that's a whole other aspect of it. Literary critics, and not just literary critics (but they're the ones who have been most vocal) have tended to dislike Franklin, sometimes to despise Franklin. D.H. Lawrence disliked Franklin immensely. Mark Twain did as well. So did any number of people because what they knew of Franklin was his autobiography where he does list these virtues and the other thing they know of Franklin is that he was the author of Poor Richard's Almanack and almost nobody read the Almanack itself; what they read was a compilation of the sayings of Poor Richard that went under the title -- a small essay -- called "The Way to Wealth" that seems to summarize this very materialistic view of Franklin as "virtue to the end of making yourself rich." So you put those two together -- this person who makes a scorecard of his virtues and the other person who says that virtues are going to make you rich -- and you think that this is a very shallow guy who is virtuous only to the extent to make money. But that was really a very small part of what Franklin wrote, for one thing, and just what Franklin lived in the rest of his life. And that's another reason, I think, that people who came across Franklin in high school are turned off, he's always telling you to eat your peas and who wants to deal with somebody like that?

AC: Did you worry about the narrative energy of the book since not even 2/3 of the way through, Franklin retires?

HB: The marvelous thing about Franklin is that he had one career after another. And he never set out at the age of 20 or whatever it might be to become a public figure; it was all he could do to make a living and to get his print shop up and going and once he had succeeded at that, then he began to think about what else he might do. Franklin is often held up as an exemplar, a prototype, of the American capitalist but he really wasn't at all. He had no sense of making money for the sake of money and, as very many very successful businesspeople do, he didn't see moneymaking as an indicator of any particular worth. So if you think of somebody like -- well, take Bill Gates -- once you make a billion dollars, the money itself doesn't mean anything; it's an indication of something else -- either you're the richest or the most successful or something like that. With Franklin, he never felt like that at all. When he had enough money to live reasonably comfortably, then he quit, he retired, when he was in his 40s, to do something more interesting. Then he used that time to go into philosophy, which is what scientific research was called in those days, and he expected that that's how he would spend most of his time.

Now he had been pretty civic-minded all along, so it wasn't too surprising that he wound up in local politics. He had no idea that he was going to go into provincial or imperial politics, but he turned out to be pretty good at it. And he turned out to be the most forceful advocate for the rights of ordinary Pennsylvanians against the heirs of William Penn, the proprietary family, but he was the one that kept getting pushed forward to do this. And he never nominated himself for anything, but people realized that he would be an effective spokesman, so he got sent off to London in the late 1750s to represent Pennsylvania to the imperial government. He might have gone to London to sightsee or something but he certainly never would have gone in any official capacity. He was pushed to run for office by other people but he was constantly trying to figure out a way to get out of politics. And even in his 80s, he kept trying to retire. But people wouldn't let him retire. Even against his will, they would vote him into office.

AC: What was the most interesting aspect of the research?

HB: Well there are two aspects of it that I found to be real interesting. One is that Franklin is known for his various bons mots -- "Nothing in life is certain but death and taxes" and all the other sayings, "There never was a good war or a bad peace" and that sort of thing -- and to be reading through Franklin's letters and just to come across where he's coining this phrase, where he thought as he's writing to a friend, and saying that in life there's nothing certain but death and taxes. My gosh! There it is. This is the origin of this saying. That was part of it. The other thing was that I was simply struck by what good common sense Franklin had. In nearly every situation he found himself in, when he was offering advice to people, it was very down-to-earth. He considered public virtue to be very important but he didn't by any means connect that with a particular religious belief; he himself was quite skeptical on the subject of religion. He didn't belong to any particular denomination. At times in his early life, he was nearly an atheist but he gradually settled back toward a semi-Christian agnosticism. He didn't believe in the divinity of Jesus, but he thought that he had a pretty good moral philosophy that unfortunately had been corrupted since he had died. He had very strong views about things but he rarely tried to enforce his views on anybody else, so I found him saying things that repeatedly struck me as being very wise. And in contrast, for example, to Theodore Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt was always saying things that were outrageous and utterly at odds with my assessment of the way the world works. Now you can make a good story out of that but this isn't somebody you're really comfortable being around for a long period of time. So he might be a dinner guest you could have over once just sort of for the spectacle of it all. With Franklin, it would be very easy to have this guy over to dinner five nights a week. To put it another way, with Roosevelt you have this sense -- and certainly his contemporaries had the same sense -- that here is a guy whose personality filled any room he walked into. If he walked into a room right now, there was something about him that would just fill up the room and take it over and that can get kind of tiring after a while. Franklin wasn't that at all. If Franklin walked into the room, you'd hardly notice him at all. And interestingly, for someone who was as successful in politics as he was, he was a very poor public speaker. ... If he had any charisma, it was the kind of charisma that worked one-on-one and not in groups much larger than that. He was really a genius but he wore his genius very lightly. ![]()