Status of the Original

By Clay Smith, Fri., Feb. 12, 1999

|

|

In late 1987, Paul Parisi, the president of Acme Book Binding, a large library bookbinding business in Boston, approached Jensen about starting a firm that would offer more "high-end" services to library binders than library binders had typically offered, with Jensen as president. Jensen returned Parisi's offer by suggesting the two of them begin a partnership with Bridgeport National Bindery in Agawam, Massachusetts, 100 miles outside of Boston. The partners then suggested that Jensen move to Massachusetts but he "dug in his heels" and decided to stay in Austin. That partnership began in April 1988 and BookLab was the partnership's local entity.

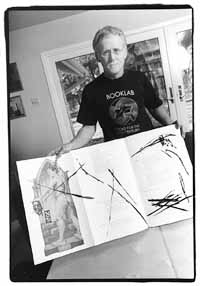

Now why should we fill this space with a story about preservation photocopy, air presses, and boxmaking, objects and notions that almost certainly mean nothing to anyone who isn't in the field? Because the story of BookLab is a classic American story, art vs. commerce, and because book artists are a bit like Italian Renaissance fresco painters: nameless. It's hard to find anyone who won't wax effusive about the artwork BookLab created, and it's just as difficult to pin down the names of particular artisans who created that art. Book artists are the people who craft safe, sturdy boxes that preserve texts that otherwise might have deteriorated to an inaccessible state; they fashion exquisite limited edition works, like Seven Deadly Sins. They're the people who take care of books that Jensen describes as "terminal patients that were dead." Because they are unseen movers in the book world, it seemed most appropriate to give them their own voice in telling the story of BookLab. Some of BookLab's former employees, business partners, and some local book artists familiar with the local book arts community recall BookLab in separate interviews that are pieced together here. They are: Craig Jensen, the president of BookLab; Priscilla Spitler, who worked at Jensen Bindery and then BookLab from

1987-95, and is the former president of the Lone Star chapter of the Guild of Book Workers and now owns Hands On Bookbinding in Smithville; Jace Graf, who worked at BookLab from 1990-96 and now owns Cloverleaf Studio, a book arts studio in Austin; Paul Parisi; Glenn Fukunaga, who never worked at BookLab but owns Handbridge Bindery in Austin and used to play bass for Joe Ely's band but "plays for everybody else now"; Jim Larsen, the president of Bridgeport Book Bindery and one of the BookLab business partners; and Carol Kent, who worked at BookLab from 1988-98 and is the former president of the Amalgamated Printers Association. Gary Frost, also a partner in BookLab and a lecturer in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at the University of Texas at Austin, was unavailable for comment.

Craig Jensen: A couple of library binders approached me to explore the option of starting a company and they asked me if I would consider being the president of that company. Well, I'd only been running my business for a few years at that point and I wasn't willing to close the doors on that and go to work for somebody else. But the notion of working with these guys was kind of exciting because they were well-established, much larger companies than I had at that time, and with this kind of business you can't just go to a bank and get capital, or you can't go to a venture capital group and say, "I want to expand this business." It's just too hard for people to get their brains around it, it's kind of esoteric and weird and they can't see where the money is, for good reason!

Priscilla Spitler: At the time they approached Craig, it was a blessing, I'll tell ya that, because he was struggling working there from six o'clock in the morning until midnight and not paying himself. He was paying his employees; I think there were three or four of us at the time. His wife was supporting him. He was falling between a commercial shop and a hand shop, trying to use machinery and equipment to move things through more efficiently but still doing really fine handwork. So when the partners came, it was a blessing because all of a sudden he had a salary and we all had security and everything that comes with it and also he loves -- he's an entrepreneur -- he loves to develop things. They wanted him to develop this preservation photocopy. There was a real void in the preservation community as to how to deal with all these brittle books. But we also thought it was a little bit strange because these were two library binderies that were in Massachusetts and they were actually competitors and in the beginning that didn't seem to be a problem.

We got a call one time from the Toronto Public Library saying, "We understand you make the largest boxes in North America," and that was because Craig had designed this unusual air press for pressing boxes and all it was was a waterbed mattress hooked up to a compressor and he had this large wooden frame built, but it was a brilliant solution to having to press these huge boxes.

Jace Graf: I've toured a lot of other bookbinderies. As a rule, they're kind of dark and kind of crowded and maybe not that clean and like an old factory. BookLab not only had great tools, we had great space, we had great light, it was clean, it was new, it was all that but it sort of attracted such an interesting collection of craftspeople or people who weren't necessarily that way when they started out but by the time they got some more training, you know, a very skilled group of people making some really interesting stuff. So there was kind of a synergy, or a kind of enthusiasm that that generated that I think was really unique. Certainly it was unique as handbinderies go just because it was so big.

Jensen: We were privileged because we got to see and handle and work with so many interesting things. I mean, it was hard, boring work at times, and how long can you stand in front of a copier or a scanner and flip pages? Well, you have to take an interest in the book itself, in what you're making and somehow we stimulated that in the people who worked for us and nobody came away feeling like a factory drone. They all took great pride in what they did and perhaps we did obsess over quality at times.

Just the level of concern, the attention to detail and quality that we had, the very robust kind of teamwork environment, the very flattened hierarchy, all of those things were quite unique and we always had young people working for us so a lot of them had nothing to really compare it to. Craft shops can really get overly obsessed and we always tried to balance the artistic side of what we were doing and the aesthetics of what we were doing with the fact that it was a business.

Spitler: The original [Ellesmere Chaucer] is at the Huntington Library in California; they believed it was the truest example of The Canterbury Tales because it was [printed] about 10 years after [Chaucer's] death. And so it's a really important piece for scholars so the Huntington Library and this Japanese publisher [Yushodo] got together and decided they were going to do facsimiles. And they had the binder from Trinity University in Dublin, Tony Cains, fly in to disbind it, you know, take apart the old binding (it had been rebound over the centuries), and it was all vellum pages and then it was photographed and then in Japan they made special paper for the project and they did special printing and did facsimile. Well, when it came to binding the edition, they wanted it bound in the same 15th-century style of binding, wooden boards, oak boards. Tony Cains said, "There's only one place that can do the binding and that's BookLab," because of Craig's background in conservation. The tragedy too is that he developed arthritis in his hands and the Ellesmere Chaucer was kind of the swan song.

Jensen: That's the glamorous, high-end side of preservation photocopy; the meat and potatoes side was just tonnage of brittle books that are really only important in the context of the whole collections that they come from; if they're missing, they become gaping holes. That's the real service we were in the business of providing.

Spitler: A lot of times we had problems trying to control [Craig]. He'd be leap years ahead, and yet we were on the floor going, "We gotta get this work out." And so there were problems in his own management and I always felt that BookLab was kind of like the problem child to the partners because we were an oddity and we couldn't fit in their little pegs, you know? They tried to put us in these little formulas and try to run us like their successful businesses but we ... didn't fit into their sense of order. The last two years, the irony of it was, were his most lucrative years.

Paul Parisi: Craig is a very talented craftsman and he has very high standards and the requirements to be a good manager are very different from the requirements to be an artist, and Craig's management skills, I think, were not as strong as they might have been. But Craig recognized that.

Jensen: I'm not the greatest organizer; I need good organizers around me to keep me under control and it took me a lot of years to come to that realization. You wrestle with your ego and all kinds of stuff.

As we really started to hit our stride and the product itself gained recognition, more and more libraries became interested in it; being a small company we literally became buried in work. And delivery of finished work became one of our biggest problems. People sent more work than we could do.

Graf: It's all custom work and it comes in whenever it comes in and you're working with small publishers who aren't necessarily the most together group anyway -- they're all artists too -- and it's all a little flaky and I think we probably did a remarkable job generally speaking in terms of keeping it organized and all that considering how wacky the whole thing was.

Jensen: I think the book thing in Austin is as much coincidence as anything else, the interest in book arts and the community of practitioners that are here. The pool of people that can do the kind of work that we needed done at BookLab I think is a direct result of the nature of the Austin community; it's laid-back, just the fact that the music scene is so vibrant here in spite of the fact that, you know, we don't have the big, giant-label successes coming, it's a chronic discussion, nevertheless it persists. I think the town itself just attracts people like that and it worked in our favor.

Glenn Fukunaga: I think that the musicians that do get into bookbinding are lucky. What it is is such an opposite effect on your brain from the music; I could be blind and still play music and I could be deaf and work on my books, they're like two opposite worlds, so I consider musicians who get into bookbinding to be lucky. Because it's a quiet world.

Jensen: The partnership just sort of wore out; I think we were very successful at defining product areas and also recognizing the areas that libraries needed to move in and articulating a vision for preservation and for preservation programs in libraries, and my partners became my fiercest competitors and I got tired of it. I felt like we couldn't expand and grow the business the way we needed to, especially with the new technologies coming online; we couldn't get the capital necessary because I couldn't really reveal to them what our plans were because it would just basically give them another good idea to go out and pursue, so I kind of blew the whistle on the thing and said, "This is it, it's not working."

Jim Larsen: The idea here is that the concept of reformatting brittle books with photocopiers was not originated at BookLab, although they were in some cases a pioneer company getting it done commercially and efficiently, so it wasn't something that started there or developed there but they seemingly perfected it. Maybe to the point where they were not able to get it out the door. And so we all, several of us, scrambled here in the Northeast and elsewhere around the country and developed our own processes and our own systems for getting that service added to the other offerings that we make to our customers.

Parisi: One of the things I think that really hurt them is that the quality and the skill that went into the work just couldn't be charged for.

Carol Kent: I don't think blame for anything should be assigned to anybody; it was part of the nature of the thing that it tended to be one of your more frustrating and difficult businesses to keep going for a long period of time. And it kept going for a long period of time and we're all bald because we tore our hair out and we look back on it fondly and charge ahead.