The Gift of Words

Corrido

Fri., Dec. 11, 1998

Fleabites Press, $12 paper

Take all the lingering ghosts and graying sages out of the American desert, and what is left? Madness, answers first-time novelist Mandy Keifetz. A gritty, guns-and-drugs place where habits and history allow no one to escape. With her blustery first novel, Corrido, Keifetz helps to create and explore this madness by collecting all the mythic spirits from the sands and placing them into the heads of her charmingly neurotic characters. After all her twisting of plot and logic, what Keifetz comes up with is a sort of hallucinogenic romance set in this empty West, a picture of the torment and craze of two lovers as they become trapped in the mirages of their relationship.

Take all the lingering ghosts and graying sages out of the American desert, and what is left? Madness, answers first-time novelist Mandy Keifetz. A gritty, guns-and-drugs place where habits and history allow no one to escape. With her blustery first novel, Corrido, Keifetz helps to create and explore this madness by collecting all the mythic spirits from the sands and placing them into the heads of her charmingly neurotic characters. After all her twisting of plot and logic, what Keifetz comes up with is a sort of hallucinogenic romance set in this empty West, a picture of the torment and craze of two lovers as they become trapped in the mirages of their relationship.

The more neurotic of these lovers is Molly Veeka, a New York linguistics professor who frequently converses with dwarfish incarnations of the dead. Her teaching routine, which is little more than a ceaseless bickering with grad students over the weightless problems of signifiers and code, is interrupted by the appearance of Goliath C. Flanagan, her on-again, off-again boyfriend who has just finished serving probation for drug-running in New Mexico. Flan, as he is called, is eager to leave the dry and paceless life of the West and settle with Molly in the anonymous glitz of New York. After becoming freshly involved in a scheme to sell a psychedelic drug called Smiley, though, he is forced to return to the desert to pick up a shipment. Molly accompanies him because she has agreed to substitute teach at New Mexico State University for her former college mentor and ex-lover, Feck, who is busy trying to sucker his way into the Modern Language Association. It is in the desert that the discomforts of their love come to the fore, opening up the narrative for the invasion of the ghosts of Molly's father and dead ex-husband.For all the complexities and quirks of her characters, though, Keifetz writes a book that is almost too clean. The visions that plague Molly Veeka are kept tightly under control, and her demons seem to pop out of the ether to spout off their thoughts and disappear once again, much like a Whack-a-Mole challenge. Also, the craze that follows Molly and Flan is often more of a torment-chic, as they spend days on happening drugs and having sex while narrating to each other the events of a 1986 World Series inning in spooky detail, clenching their jaws all the while.

What makes the novel a satisfying read is Keifetz's right-on grasp of events and details that elevate the common into something nearly precious. Her description of Molly Veeka's favorite baseball team as "the tang of strive and failure, or labor in obscurity, underdog magic, long muscles stretching under sweaty skin" may as well be the epitaph for the wilting love between her characters, or for the doomed inhabitants of her vast desert. It is in moments like this that the insanity of her book opens itself up to reveal its rich nature, one of drugs and sweat for sure, but also one of cooling earth at night, and of sadness. -- David Garza

Evening

Evening

by Susan Minot

Alfred A. Knopf, $23 hard

Many women read catch-yer-man magazines like Cosmopolitan without greeting dates at the door wearing only Saran Wrap; many girls who play with Barbie dolls aren't scarred by anorexia. This is a feminist's apology for enjoying books, magazines, and dolls which portray women as essentially one-dimensional and pathetic. Susan Minot's latest novel Evening requires such an apology -- it's a thoroughly pleasant read even as it depicts lame, dependent girldom.

The novel intercuts between narratives in the present and the past as Ann Grant Katz Lord Stackpole dies a slow death amid family and friends. She drifts in and out of consciousness and vividly relives memories, specifically the sad story of her first love: It was the summer of 1954, with the 25-year-old protagonist a bridesmaid at her friend's high society wedding. The wedding party is a motley crowd of Massachusetts aristocracy, romping as only the wealthy can. In the course of the weekend, Ann meets an engaged and obligated ladies' man and falls madly in love, only to have the inevitable denouement disillusion her for life. Playing on the contrast between these two scenes, Minot hauntingly portrays the crushing clarity of star-crossed love affairs while evoking the otherworldly intensity of the deathbed.

Minot is also deft at portraying a life essentially wasted on the pursuit of love. All along, Ann has remained unambitious and utterly dependent upon men to define her. She has that yearning that dominates all else, even her very self. Such a woman, as Minot portrays her, is at once sympathetic, fascinating, and tragic. Always waiting for the next life-giving love, the heroine sees every flawed man as her newest savior. The weary, heartbroken moral of this novel is typical for Minot and many cornerstone works of women's lit: Even though men can spark women's awareness of themselves (Titanic anyone?), women can't continue to rely upon their lovers for spiritual sustenance. Simply put, it's better when inspiring men go down with the proverbial ship. Ann never learns this lesson. Right up until the end she is asking questions like "Where is inside? Can we go there together?" and begging this man from her past not to leave her, this man who had abandoned her 50 years before.

Evening does, in all this whininess, occasionally grate. There are frequent clusters of unpunctuated clauses. For example, "I am here swimming up from this sea I am here I was there I was always there your true self your truth I was never gone and though you thought it came from him it was really yourself." Some passages like this ramble on for half a page, and while Minot's intention is to represent the processes of a brain addled by both medication (deathbed Ann) and love (wedding party Ann), the italicized voice begins to sound affected and overbearing.

Nevertheless, even in its affectation, Evening fits squarely into the horrible, wonderful women's literature genre. Minot's heroine is stirred to life by love and yet hasn't a clue how to make proper use of her illumination, much like the heroine of such classics of the genre as Kate Chopin's The Awakening. Evening, like The Awakening and its ilk, is a solidly enjoyable read even as it offers a profoundly depressing view of womanhood. -- Ada Calhoun

The Amazing "True" Story of a Teenage Single Mom

by Katherine Arnoldi

Hyperion, $16 hard

As a person who has generally been rather short on sympathy (I'm ashamed to admit) for women who've had surprise or unwanted pregnancies, and who steels her jaw and rolls her eyes at the mere mention of teen motherhood, I wasn't expecting to get very much out of Katherine Arnoldi's comic-book-style memoir, The Amazing "True" Story of a Teenage Single Mom. But since my own postpartum hormones have finally simmered down to a dull throb, I can only attribute the hot tears I shed while reading it to the power of Arnoldi's moving, triumphant story.

Unloved, unwanted, unparented, physically brutalized, and a mother at 17, Arnoldi's journey toward self-realization begins in the allegedly enlightened Seventies with a hazardous job in a factory, where she strips latex gloves off ceramic forms. Nights, she takes a shift in a steak house (the sort of place where a woman had to dress up like a buxom, saucy wench -- so popular in that decade of deception), where she's warned that she needs to "loosen up" and smile if she wants to get anywhere.

With so much pain behind her, there wasn't much to grin about. But deep inside, Arnoldi smiles with a secret: She wants to go to college -- for herself, and for the little daughter she loves so very much. For, despite what she'd always been told, Arnoldi suspected she really was worth something. "I wanted to be treated like someone becoming someone, not like someone to be kept in her place," she writes.

There are more than a few obstacles in her way -- rapists, abusers, uncaring family members, and devastating poverty. Have we heard this before? Yes, too often, and unfortunately, the retelling of it on daily, syndicated talk shows has almost desensitized us to its effects. But Arnoldi's story works on two levels, with words and with pictures, as defenders of the frowned-upon "comic book" would tirelessly remind us. A boyfriend who had once offered so much hope, the promise of love, the possibility of change ... now, he shows his true, brutish colors. He's rendered monstrous, terrible, bug-eyed. The words, "You got anything to say for yourself now?" are encrypted into his inky, devil's face, after he has finished beating Arnoldi black and blue.

But all bad things come to an end. When Arnoldi learns that she has been accepted into college, she draws herself and her child as though they have entered into a new world all their own, swirling, twirling, flying, with absolute, unimaginable joy. And that's the note she leaves us on, with a friendly reminder: "Young women with children need compassion and empathy. Help a mother today!" Because of you, Katherine Arnoldi, I will, and keep my judgments to myself. -- Roseana Auten

Dead Languages

by David Shields

Graywolf Press, $12.95 paper

Most people can talk a good game. Because words that flow effortlessly from our mouths are never seen and rarely heard again, speech is fleeting, conversations casual. Writing, which doesn't offer the chance to clarify or reiterate, is a different story. The durability of the written word makes the best speakers self-conscious enough to stumble, fumble, rework, and rewrite the words that explain a simple idea, words that would take only a moment to say.

Most people can talk a good game. Because words that flow effortlessly from our mouths are never seen and rarely heard again, speech is fleeting, conversations casual. Writing, which doesn't offer the chance to clarify or reiterate, is a different story. The durability of the written word makes the best speakers self-conscious enough to stumble, fumble, rework, and rewrite the words that explain a simple idea, words that would take only a moment to say.

Such is life for a competent, confident speaker, but this means nothing to Jeremy Zorn, the stuttering hero of David Shield's Dead Languages, originally published in 1989 and re-released this year in paperback.

Each member of the Zorn family is a wizard with words: Jeremy's mother is a highly successful, if tyrannical, writer, his sister a student of the theatre, and his father wins invitations to Hollywood parties for his flawless delivery of jokes. In contrast, Jeremy stutters so badly that he can't even say his own name.

From the time Jeremy is a toddler until he graduates from college, he relates the major events in his life story from the angle of a disfluent speaker. It's a sad story, but not just because of the stuttering. It may be Zorn's disfluency that leads to his unpopularity and dejected sense of humor, but these things swell into problems of their own.

But life isn't all bad. Until he breaks his leg in a high-school suicide attempt, he excels at athletics. And in the book's greatest irony, Zorn masters language by becoming a successful writer.

This is no surprise to someone reading the book, a first-person narrative. Shields presents the anguish of Zorn's lifelong struggle with language so clearly that it must be an autobiographical tale.

From the development of characters to the strength of form to the use of metaphor, Zorn has nothing to complain about. It is hard to concede that this highly articulate man, Jeremy Zorn, has a problem with languages. Unlike the majority, this protagonist may not be able to speak, but he certainly can write. -- Meredith Phillips

The Museum Guard

by Howard Norman

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $24 hard

Howard Norman's previous novels, The Northern Lights and The Bird Artist, were finalists for the National Book Award. Norman's latest is The Museum Guard, which is written in a delicate tone reminiscent of William Trevor. The story follows DeFoe Russet, orphaned at birth and now a young guard in a Halifax, Nova Scotia art museum, the Glace Museum.

Howard Norman's previous novels, The Northern Lights and The Bird Artist, were finalists for the National Book Award. Norman's latest is The Museum Guard, which is written in a delicate tone reminiscent of William Trevor. The story follows DeFoe Russet, orphaned at birth and now a young guard in a Halifax, Nova Scotia art museum, the Glace Museum.

Throughout the book, despair hovers overhead like the zeppelin that crashed years before, killing DeFoe's parents. It is 1938; the news from Europe is bad. DeFoe lives quietly in the Lord Nelson Hotel, one floor below his irresponsible uncle (and co-worker), Edward. Permanently rumpled, Edward counterbalances his cautious nephew, who is quite meticulous -- DeFoe is the type who will iron 30 shirts at a time and think nothing of it. The object of DeFoe's affection, Imogen, oversees the nearby Jewish cemetery. Eventually, he can't stand being away from her, so much so that he steals a painting from the Glace she's obsessed with, Jewess on a Street in Amsterdam. He is smitten, but Imogen, it turns out, may be involved with Uncle Edward.

As DeFoe becomes consumed by Imogen's strange fixation, he abandons his routine, launching Edward, Imogen, and DeFoe himself in a fateful trajectory. Imogen has taken to dressing and speaking like the Dutch woman in the painting. Soon after, she becomes compelled to travel to Amsterdam. In spite of grim reports originating from there, Edward and DeFoe are nevertheless willing to send her, for reasons that remain decidedly unclear.

The Museum Guard addresses lofty issues -- identity, history, loyalty -- but this ethereal story ultimately remains earthbound. Viewed solely as a work of painterly detail, the novel is world-class. However, two murky clouds never lift from The Museum Guard: What is the true mystery that compels Imogen? Precisely what is it about her that puts such a spell on the two men? Like a painting, The Museum Guard is open to interpretation. -- Stuart Wade

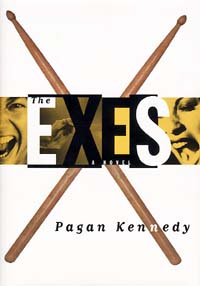

The Exes: A Novel

by Pagan Kennedy

Simon & Schuster, $23 hard

What happens when two ex-lovers form an indie-garage rock band made of other ex-lovers? That's the premise behind Pagan Kennedy's latest novel, The Exes, but the story, like most local bands, ends without fanfare and without warning. So what happens? Much the same as when four complete strangers or four friends, talented or not, throw themselves into a musty, tiny basement, pick up their instruments or their sticks, turn up the volume, and play -- magic. Well, magic and mediocrity. Fights and make-ups and break-ups. Egos clash, insecurities surface, and every once in a while, some music results.

What happens when two ex-lovers form an indie-garage rock band made of other ex-lovers? That's the premise behind Pagan Kennedy's latest novel, The Exes, but the story, like most local bands, ends without fanfare and without warning. So what happens? Much the same as when four complete strangers or four friends, talented or not, throw themselves into a musty, tiny basement, pick up their instruments or their sticks, turn up the volume, and play -- magic. Well, magic and mediocrity. Fights and make-ups and break-ups. Egos clash, insecurities surface, and every once in a while, some music results.

Hank and Lilly were lovers. Fierce, passionate, crazy lovers who couldn't get along, were jealous and violent, and hated each other as much, if not more, than they loved. Hank was controlling. Lilly was wild. He told her how to play the guitar right and yelled at her for wrecking his bike. She smashed his collection of vintage eight-tracks and left him standing in a room of floating tape ribbon. A week after they break up, they form a band. "We'll call ourselves the Exes," says Lilly. "And the thing is ... everyone in the band will have gone out with someone else in the band. ... We'll have the gossip factor." Cute. And, for band and book, it works, for a time. Hank finds Shaz, a bisexual, Pakistani funk 'n' groove bass player and Lilly woos her into the band. Shaz brings ex-lover number four, Walt, a Harvard grad student who's just out of the loony bin, but mean on those skins. And together they rise from Sunday night, $20-a-pop gigs to semi-stardom.

Each section of the novel is devoted to one of the Exes and their particular story -- their fears, their hopes, their heartbreaks -- and the best and most sincere section is Walt's. Walt is lost in his world of biology and deep thinking. He wants to be a normal guy but can't quite manage -- no Monday night football games and beer with cheezy poofs for him. He is the mystery man of the band. He is quiet and shy with his shaggy hair and ripped shorts, and in the final section of the novel, we are rewarded with a peak into his rim-shot thoughts. His story and his voice are both endearing and make for a nice ending to this somewhat mediocre novel.

Maybe I'm jaded, living in Austin, having played around town in this band or that, but much of the description of band life sounded, well, researched rather than lived. Her description of the music felt muted and almost secondary, but maybe for her, the music was secondary, but then why not just write a novel about four ex-lovers and their lives as they intertwine? In the end, The Exes is about as enjoyable as any number of bands tooling around Sixth Street or the warehouse district -- fun for the ride but not too memorable. -- Manuel Gonzales