Texas Book Festival Wrap-Up

Fri., Nov. 20, 1998

|

|

Moderator Lorenzo Thomas started off with an open-ended question, based on a comment he'd heard on public radio from poet Al Young, that poetry was meant to "sweeten the tongue," thereby "elevating the language," and by extension, "elevating the thought." He asked Cyrus Cassells, Edward Hirsch, and Leslie Ullman, three of the highest-profile, university-affiliated poets in the state, to provide answers to how this is done. The trio responded with the kind of carefully thought-out, solid responses you'd expect from committed poets who have logged a lot of classroom time.

| Minding the Muse: Poets on Their Inspiration Moderator: Lorenzo Thomas; with Cyrus Cassells, Edward Hirsch, and Leslie Ullman |

Ullman, in particular, provided some of the most useful nuts-and-bolts information regarding poetic inspiration, including keeping a journal "with no literary value whatsoever" in order to write her way through problem poems which are, for whatever reason, not doing what they are supposed to do. Hirsch was more esoteric, but perhaps more realistic, about the craft of poetry in pointing out the necessity of tapping into the unconscious. "The moments which are most thrilling for me," he said, "are when I write something better than I have before and when I write something I hadn't planned." Cassells flatly stated he needed a "near-death" experience on a turbulent airplane to get him to the place where he could risk attempting love poetry, given love poetry's often-attendant sentimentality and its overall degree-of-difficulty rating.

All agreed with Hirsch's observation that poetry is both "a made thing" and "a form of stored magic," and in reading from their work, they displayed a cunning command of poetic language and form. It didn't show the audience where the rabbit really is during the hat trick, but it did hint that poetry's making requires a deep appreciation of magic rather than an actual, card-carrying magician. ó Phil West

|

|

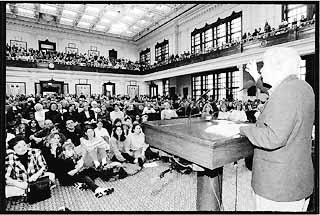

Frank McCourt spent most of his first 18 years in Ireland as a peaked, underfed, God-fearing Catholic youth, and he is keenly aware of the irony of his fame. Before he read the bit of his book about practicing for a First Communion, Frank McCourt said, "Here's a scene from Angela's Ashes, which I wrote and made a lot of money from because it's all about misery and poverty." That sentence could be read as a bitter one but it shouldn't be ó it's just a perfect example of Frank McCourt's casual, unpunctuated voice. It's the voice of a child ó and now an adult ó trying to make some kind of order of the ironies in life, and it's highly recognizable to anyone who has read Angela's Ashes, his Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir.

| Reading: Frank McCourt |

During the reading, McCourt chose a few parts that left the audience with smile lines; he read about his experiences with dancing lessons, about Irish schoolmasters, and about how his little brother was rewarded with sweets for cramming their father's false teeth into his head, while he himself ended up having to have an operation.

Like most of the best storytellers, McCourt is not a flawless orator. In his speech, he uses run-on sentences to convey his child-like observations and their natural conclusions, as he does in his writing. The effect of his wide-eyed point of view is brilliance.

But as he told us, "When I was a teacher nobody paid me a scrap of attention." It wasn't until he retired that he compiled the stories of his youth into one of the funniest, saddest, and most read books of our time. Suddenly, everyone started paying attention.

Soon McCourt will release another book, this one about his 30 years as a teacher in a New York public school. And judging from the awed and eager turnout to his reading at the Texas Book Festival, he definitely has everyone's attention. ó Meredith Phillips

"People experience intellectual awakenings in different ways," began Michael MacCambridge, author of The Franchise: A History of Sports Illustrated Magazine. For MacCambridge and countless others, the Christmas they received their first subscription to Sports Illustrated ushered in a kind of adolescent age of enlightenment. Every week fans were treated to gripping tales of larger-than-life sports heroes brought to them by a larger-than-life stable of writers. If sports is a publication's toy department, SI helped sports writing become less Toys R Us and more Sharper Image.

|

|

Sports Illustrated legitimized sports for intelligent people," MacCambridge asserted. This was chiefly due to its brilliant stable of writers. (Plimpton and Shrake's colleagues included Dan Jenkins, Roy Blount Jr, and Frank DeFord, to name a few) and editors like Andre Laguerre. "I was quite terrified of him," confessed Plimpton, as Shrake nodded in agreement. The two spoke with a cub reporter's awe of Laguerre, whose vision drove the magazine and its writers. Laguerre urged his writers to take risks ó not to mention staying at the priciest hotels and eating at the finest restaurants because he believed it bolstered the magazine's reputation.

| The Franchise: The Glory Days of Sports Illustrated Moderator: Robert Draper; with Michael MacCambridge, Bud Shrake, and George Plimpton |

Like aging athletes and the fan who memorizes all their stats, Plimpton, Shrake, and MacCambridge regaled the crowd with tales of past glories and griped about today's SI. Over the years, the magazine has fallen victim to a shift not unlike the one in the sports it covers, with money and marketing becoming the forces that drive the bus. The writing is no longer clever or brave, they complained. And the proliferation of ESPN and its cable television progeny have hurt the once-dazzling magazine. It's harder for an intellectual fan to legitmize a love for sports these days. There are few literary lions in sports journalism; fans who once chatted about a Plimpton or Shrake story now recount SportsCenter commercials. ó Lisa Tozzi