The Texas Book Festival

Chapter Three

Fri., Nov. 13, 1998

So much of the discussion about what it means to be a good person in this world has been taken over by strident numbskulls, from William Bennett to Jesse Helms to Dr. Laura Schlessinger. For my money, you will find no "book of virtues" like the deceptively unassuming memoirs penned by medical doctor Abraham Verghese. For people trying to figure out how to live in a world half-ruined by sad epidemics -- AIDS, drug addiction, divorce -- as well as the ordinary corrosive action of human weakness, the work of Verghese is mission-critical.

So much of the discussion about what it means to be a good person in this world has been taken over by strident numbskulls, from William Bennett to Jesse Helms to Dr. Laura Schlessinger. For my money, you will find no "book of virtues" like the deceptively unassuming memoirs penned by medical doctor Abraham Verghese. For people trying to figure out how to live in a world half-ruined by sad epidemics -- AIDS, drug addiction, divorce -- as well as the ordinary corrosive action of human weakness, the work of Verghese is mission-critical.

His first book, My Own Country, named one of the best books of l994 by numerous critics and Time magazine, told the story of how this African-born Indian physician helped rural Tennessee families face the dawning of the age of AIDS. As returning prodigal sons came home to the Smoky Mountains with the then-new affliction, Verghese -- in his first job out of medical school -- was the one to meet them, to treat them, and to guide them through the emotional and social challenges of living with and dying of AIDS in the heart of redneck country.

To that story, as to the new one, he brought a threefold gift: the gift of the doctor, rigorous observation and reasoning; the gift of the storyteller, warmth, wit, and well-chosen words; and the gift of the wise outsider, fresh eyes. He also brought something quite uncommon in great men of medicine and of letters: an utter lack of arrogance. Verghese's humility is the flip side of his receptivity to all varieties of human experience. He is not afraid of or horrified by any way people are; on the contrary, he is interested.

In The Tennis Partner, Verghese tells another sad story. After Tennessee, the good doctor moved to El Paso, stranger again in yet another strange land. To compound his adjustment problems, his marriage fell apart as soon as he got there: He spent the period of time described in the book living in a bare apartment with only an upside-down, pizza-stained U-Haul box for furniture. Since the only regular visitors were his two sons (one of the pleasures of this book is its sweet rendition of single fatherhood), it didn't much matter.

But then onto this lonely stage strides a compelling new character: a blond medical student from Australia named David Smith, who like Verghese is a tennis player. "Player" is an understatement in both cases: Verghese is a fanatic amateur, and Smith is a former pro. Beginning with a weekly workout together on the court, the two men become best friends. So many men don't even have best friends, and perhaps those that do don't often write about them, because Verghese's writing about male friendship seems very rare. He gets all the little moments of friendship just right, from the excitement and near-infatuation of the early stages, to the security and even smugness of pal-dom, the interdependency, the shared rituals, and then, suddenly, the bewilderment as this relationship motors at full speed into a black cavern.

As it turns out, David Smith has another "friend" that Verghese must compete with: Mr. I.V. Cocaine. As Verghese gradually realizes, with the naïveté of one who has only seen drug hell from the outside, Smith's addiction compromises his integrity to the point that Verghese is ultimately having a relationship with an illusion, a projection, a person who is not really there. To love an addict is the loss that keeps on losing: There is always something more to go until there is finally, literally, nothing at all. And yet Verghese takes the reader with him on this journey in such an open-hearted, full-spirited way that you are never sorry you bought a ticket for the whole ride.

A primary function of memoir is to preserve lost time and lost people, to create a record of what has been taken from us. To fight death with memory: with life. Now David Smith need never be forgotten. His friend has made sure of that. As medicine heals the body, art heals the soul. This book and the life of its author stand in testimony to both parts of that statement. -- Marion Winik

Abraham Verghese is a panelist in the "First Person: Why I Wrote a Memoir" panel on Saturday, 2:30pm in Auditorium Capitol Extension Room E1.004 and will give a reading on Sunday at 11am at the same location.

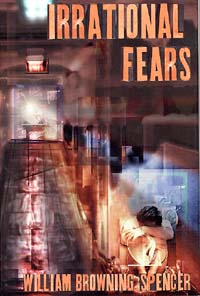

Irrational Fears is a very, very funny book if you're not afraid of humor that rustles through the dark attics of human behavior. And if you're not averse to caustic satire. And if your anchor to reality can withstand a full frontal assault without flinching. This latest novel by William Browning Spencer is an irreverent intrigue that gently tweaks Alcoholics Anonymous while using it as a framework to prop up the story. (Spencer makes it very clear that AA, despite its quirks and the fun he might poke at it, really works.) It's a bizarre tale of disenfranchised college professor Jack Lowry, who is dragged into reluctant battle with various demons -- real and surreal.

Irrational Fears is a very, very funny book if you're not afraid of humor that rustles through the dark attics of human behavior. And if you're not averse to caustic satire. And if your anchor to reality can withstand a full frontal assault without flinching. This latest novel by William Browning Spencer is an irreverent intrigue that gently tweaks Alcoholics Anonymous while using it as a framework to prop up the story. (Spencer makes it very clear that AA, despite its quirks and the fun he might poke at it, really works.) It's a bizarre tale of disenfranchised college professor Jack Lowry, who is dragged into reluctant battle with various demons -- real and surreal.

But it's also a two-by-four across the forehead that unsparingly delivers the cold, hard truths and consequences of excess drink. The misery and emotional squalor of alcoholism inhabit every syllable. Is this the typical stuff of laugh-a-minute comedy? Hardly. Nor does Jack Lowry cut a heroic figure.

Jack makes his first appearance in the Seventh Street Hurley Memorial Detox suffering from an extended gin spree. As he travels the rocky path to sobriety and beyond, he is haunted by the murder of his platonic, forbidden lover, Sara. He finds solace and kinship in young and pretty rehab patient Kerry, but she soon runs afoul of bad characters. Jack and a band of fellow AA Twelve-Steppers are soon in seriocomic pursuit.

This odd troupe bounces in and out of rehab centers and AA meetings all the while giving chase to The Clear, an H.P. Lovecraftian cult who are clearly Not Friends of Bill W. When The Clear are around, people disappear and strange things happen. And when the good guys aren't facing down the cult, they're struggling to keep themselves on the straight and narrow. This is one booze-soaked novel, and there is no cocktail-party glamour to it.

Readers might have trouble getting their bearings when the proceedings shift from the real to the surreal. It's disconcerting when characters lurch from one plane of reality to the next without the slightest warning or clue. Time and space transitions are, I suppose, a tricky business to navigate. But the havoc eventually dissipates and the plot's internal logic asserts itself. To the extent, of course, that internal logic can explain dead people in mirrors, body parts that double as time/space portals, and an endless loop replaying an accidental death. You're advised to check your disbelief at the door.

The reluctant adventurer Jack Lowry parlays a certain amount of Woody Allen-style angst into a not unattractive personae -- beleaguered urban intellectual and master of the scathing bon mots. He's cloaked in an appealing defenselessness with the whole world (or worlds, in Lowry's unfortunate case) arrayed against him. The sardonic observations reek of truth, but too much buzzsaw wit is sometimes just a buzzing whine.

Ultimately, Irrational Fears succeeds as a brutally frank redemption story masquerading as a quirky fantasy. It is Jack Lowry's gimpy-legged long walk back from the edge of despair to ... well, a couple steps back from the edge of despair. But maintaining the status quo apparently counts as a victory in the rehab game. The fantasy elements can be jarring, but Spencer remains a writer of uncommon skill and the sparkling gems in Irrational Fears far outshine its dark subject matter. -- Mike Shea

William Browning Spencer is a panelist in the "On the Edge: Speculative Fiction" panel Saturday, 12:45pm in Capitol Extension Room E2.104.

Who'd have thought an ongoing series of novels featuring an unlikely duo of East Texas roughhousers -- one black and gay with a penchant for setting fire to crack dens, one white and straight with big fists and bigger insecurities -- who find themselves caught up in an increasingly bizarre series of outlaw mercy missions would have such staying power? Not fans of Tom Clancy, certainly, but then again Clancy's ilk aren't likely to have caught on to the phenomenon that is Joe "Deputy Dawg" Lansdale. Of course, here in the Lone Star state the Nacogdoches-based former potato baron and kung fu bad mama jama is as sacred as Shiner Bock, a literary native son with one foot firmly planted in the pulp storytelling traditions of a bygone era and the other rooted in his own weird, wild East Texas, where drive-ins and time traveling critters from hell go hand in hand. Rumble Tumble is the fifth of his novels to feature protagonists Leonard Pine and Hap Collins, and this time, as before, Lansdale's plotting makes Mr. Toad's Wild Ride seem like a spin in a rubber baby buggy bumper: "Outrageous" is putting things mildly. Rumble Tumble opens with Hap mooning over his lady love Brett Sawyer and that eternal question "to live together or keep on taking up space on Leonard's couch?" With a less-than-satisfying job as a bouncer at the local topless bar, his self-esteem is woefully low, and the day-to-day considerations of romantic entanglements such as his are seemingly beyond him. The point is rendered moot when Brett receives information regarding her wayward daughter, Tillie, who's in deep in the Oklahoma underworld of sub-adult entertainment and questionable moral quandaries. As related by the Tony Llama-shod midget Red and his gargantuan traveling companion Wilber, Tillie's on the outs and looking for an escape route. It's up to Hap and Leonard, then, with Brett in tow, to save her from a Lansdalian fate worse than death. From here on out, Rumble Tumble is a road 'n' rescue novel of epic nasty proportions, filled with pilots, angry midgets, and renegade bikers that make Charles Manson look like Paul Lynde.

Lansdale's writing owes plenty to Western authors such as Zane Grey but with its own unique twist; it's an unselfconscious stream of adventure/disasters that pile up one on top of the other until friend and foe alike are face down in the gutter, covered with either blood or bile and moaning about going home as soon as possible if you please. As a regionalist, he's beyond compare: His ability to capture the skewed, East Texas world of these low-rent, bighearted heroes and horrors is riveting, and though the violence he became known for as part of last decade's "splatterpunk" movement (a movement he actually may have started with his early-Eighties novel The Nightrunners) is still as bloodthirsty as ever, it's Lansdale's goofy, improbable sense of humor that sticks with you more than the red stuff. Late 20th-century American storytelling at its oddest, this is Lansdale firing on all cylinders, horror, humor, and pathos wrapped up in a barbed-wire 'n' badass souffle. Eat up, but mind the pointy bits. -- Marc Savlov

Joe Lansdale will read from Rumble Tumble Saturday at 2pm in Capitol Extension Room E2.016.

A majority of the nation's writing instructors must be heartily espousing the tenet that every life has material that's ripe for recollection. Judging by the plethora of memoirs and autobiographical books that are making it to bookshelves, a great majority of their students are taking it to heart. Actually, there's no reason they shouldn't -- everyone does have a story to tell. UT English professor Laura Furman's is more prescient, precise, and inviting than most.

A majority of the nation's writing instructors must be heartily espousing the tenet that every life has material that's ripe for recollection. Judging by the plethora of memoirs and autobiographical books that are making it to bookshelves, a great majority of their students are taking it to heart. Actually, there's no reason they shouldn't -- everyone does have a story to tell. UT English professor Laura Furman's is more prescient, precise, and inviting than most.

In a memoir, major life events have a way of becoming narrative climaxes whether the writer wants them to or not, and in Ordinary Paradise, it's almost as if Furman doesn't want those events -- her mother's death from ovarian cancer and her own diagnosis with the disease -- to eclipse the everyday story she has to tell. Maybe that's because she grew up learning not to dramatize what was inherently dramatic; at one point in Ordinary Paradise, Furman reports that "when real drama came to our family, we pretended that everything was normal, and that was our form of theatre." Nevertheless, she describes her mother's death as "the shipwreck of my early life," and though her mother's death and its enduring emotional aftershocks consume many words in Ordinary Paradise, Furman doesn't build the narrative around that single catastrophic event. Just as critical to the success of Ordinary Paradise is the kind of non-sequitur recollection of apparently inconsequential occurrences. Writing about her family's country house in New Jersey (Laura Furman grew up the middle of three girls in Manhattan), she remembers that "when friends came to us, my father grilled chicken, and the grownups tried to leave their glasses in drink holders that were stabbed into the ground and never stayed upright, but never fell." Extracting that sentence from its surrounding, the obvious question is why the stance of drink holders matters. But sentences like that one, frequent throughout Ordinary Paradise, impart place and feeling to the text, duly reflecting the nature of memory, which isn't always orderly.

If it strikes you as odd, a bit regal, that a writer should begin describing a seemingly casual setting, friends coming over for dinner at a country house, by saying "when friends came to us," here again there's a method to Furman's technique. Several sentences earlier, Furman writes that her parents "went for drinks" to someone else's house: Ordinary Paradise is so rigorously phrased that if in one preceding sentence Furman uses "went," you can be certain "came" will soon follow. Someone who writes rigorously doesn't always write elegantly, but Furman bridges the gap. For example, this is how she describes her father getting out of the pool: "Once out of the pool, he began walking down the concrete path to the house, through the dew-wet lawn, wrapped in the towel he'd left in wait." "Left in wait"? Most people leave a towel waiting by the pool, just sitting there. This poetic stance Furman adopts is at the core of her tale, and it engenders a sense of distance and even at points a heartfelt majesty to the plot, which isn't merely strung-together poetic impressions. For someone who says she's led "a lifetime of feeling unprepared," Laura Furman is evidently on top of it all in Ordinary Paradise. -- Claiborne Smith

Laura Furman is a panelist in the "First Person: Why I Wrote a Memoir" panel, Saturday at 2:30pm in Auditorium Capitol Extension Room E1.004.